The recent sale of Bob Dylan’s one-off recording of “Blowin’ in the Wind” for $1.7 million dollars has left me reflecting on a very different way of evaluating art and distribution.

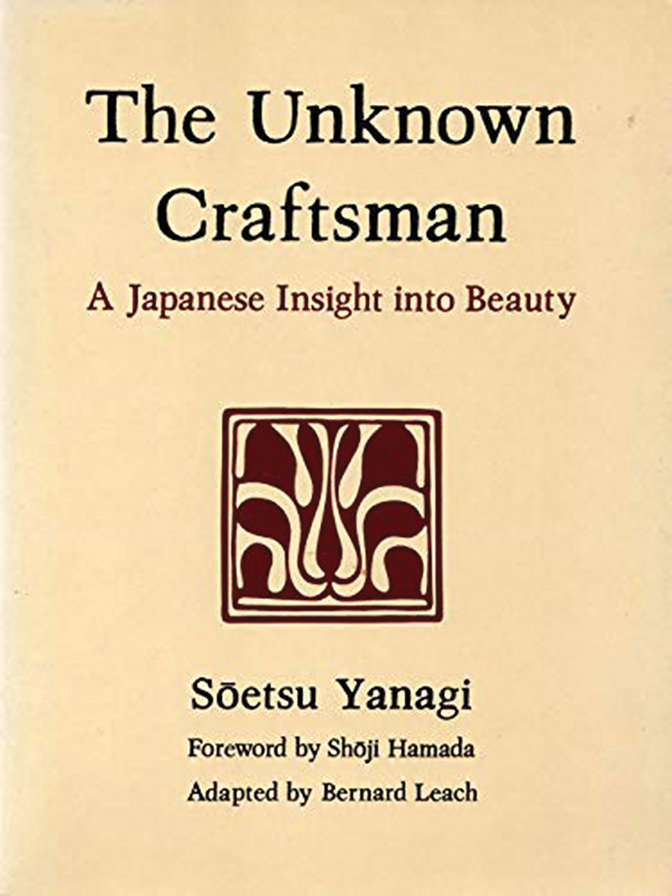

The Unknown Craftsman: A Japanese Insight into Beauty is a book of the writings of Sōetsu Yanagi, a philosopher and founder of the mingei (folk craft) movement in Japan in the mid-1920s. Mingei celebrates the beauty in everyday handcrafted objects, such as ceramics and furniture, and how they bring daily beauty into the lives of so many people. These pieces of art are made with care, patience, and skill by craftspeople, ones who are, for the most part, anonymous and unknown. In the surfing world, mingei is often referenced to contrast handmade and hand-shaped surfboards (how all surfboards were once made) against machine-made factory surfboards (how most surfboards are now made). As an avid surfer, I can attest to the functional “magic” of a well-made, hand-shaped surfboard.*

There are a lot of parallels to pop music here. These days, with the omnipresence of consumer culture and influencer-based social media, nobody is anonymous anymore, not surfboard shapers, and certainly not most successful pop musicians and record producers. But, at its best, a well-crafted pop song is a work of art that (now, more than ever, with streaming services) can enrich the lives of many, bringing beauty and culture into the lives of millions of people – ones who might not be able to afford to fill their lives with “high art.”

When Bob Dylan first released “Blowin’ in the Wind” in 1963, this was certainly the case. This simple, beautifully crafted, heartfelt song reached millions of people, and its message helped shape the course of society in the 1960s. To see this song re-recorded by T Bone Burnett (Tape Op #67) as part of his Ionic Originals series, and then sold to an obviously extremely wealthy person for $1.7 million dollars, saddens me in a way I cannot entirely express. I fail to understand the motivation here by Mr. Dylan and Mr. Burnett.

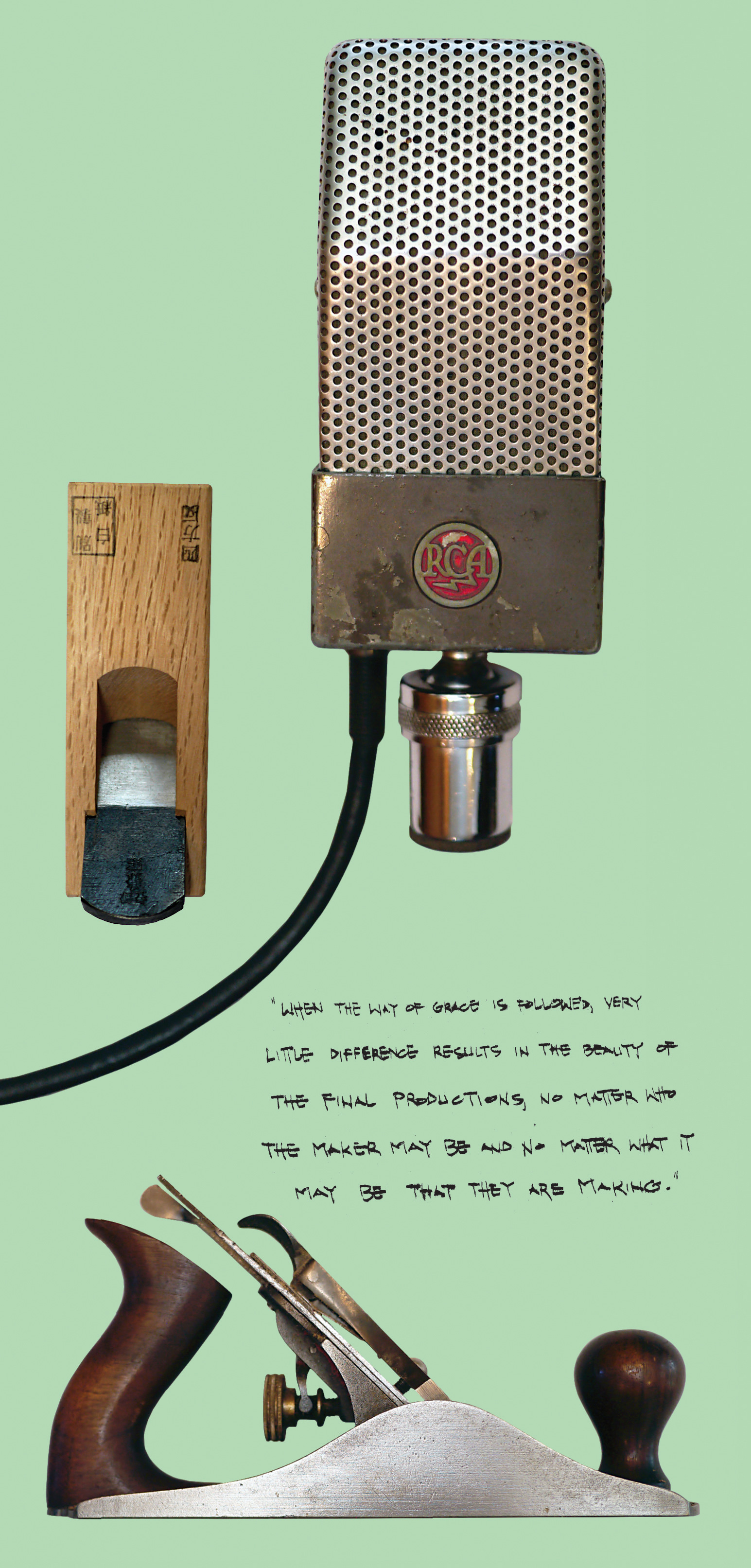

Mr. Burnett, to Chris Willman at Variety, explained his process as the antithesis of mass consumption, “We are not contriving scarcity. This is actually scarce,” he says. “It is a unique, handmade, original recording. We have all been conditioned to accept the terms of, and react to, things from the frame of mass production. This is not that. This is a full rebellion against mass consumerism. This is about high art.”

Whatever Mr. Burnett’s motives are here, The Unknown Craftsman he is not. Creating music that only the top one percent can afford (or even listen to) seems to be the ultimate expression of commodification, and simply saddens me. Sure, I’m frustrated with how streaming services have devalued music, but they’ve also brought music into the lives of many people who likely do not have the income to buy limited edition vinyl releases, let alone a one-off million dollar Ionic Original.

I own and enjoy quite a few albums that T Bone Burnett has produced, and Bob Dylan’s “Murder Most Foul” was one of my favorite songs of 2020. These two have made and shared art that has changed and informed my life for the better. I have had so much admiration for Mr. Dylan and Mr. Burnett, but this action doesn’t feel very rebellious to me. Instead, this comes across as fully being a component of the same consumerism they claim to be fighting against.

-JB

The original version of “Blowin’ in the Wind” was certainly meant to be heard and shared. It is a thoughtful protest song, in an era that needed new, strong rallying cries against governmental wrongs that had occurred and were building to a head (McCarthyism, the Vietnam War, the ongoing fight for civil rights). At its very least, it was a plea towards understanding our fellow humans. Dylan was a cocky, young songwriter who took on Greenwich Village quickly, and he could see there were more almost performers than songs there in the early ‘60s. “Blowin’ in the Wind” did far more than provide his peers with a song to cover, it became something much larger because it spoke to people and was shared with the world. Not sold off to some millionaire and never heard by others. For much more original context, see my review of Richard Barone’s [Tape Op #54] new book, Music + Revolution: Greenwich Village in the 1960s, this issue.

-LC

* Shout outs to Bob Pearson (Arrow Surfboards) and Ryan Lovelace (Surf | Craft).