Anyone who's been around me for the last few months probably knows what's on my mind. I have a big mouth and I usually mull over aloud the topics that make up these 'end rants' for a while until they gel in such a way that I can go forward and write the darn thing. As I've been formulating this one I probably bent the ears of too many clients, friends, students, and TapeOpCon attendees.

What is the one thing that separates great engineers and producers from the teeming hordes? These days it's so easy to go out and purchase a pile of recording gear that can do a great job of recording many tracks of high quality sound, with fairly clean preamps and affordable mics that do the job well. So why do I hear so many shitty sounding home recordings? And why do I always strive for better-sounding recordings when I'm working and cry when I hear how good the new Grandaddy record sounds next to the stuff I track?

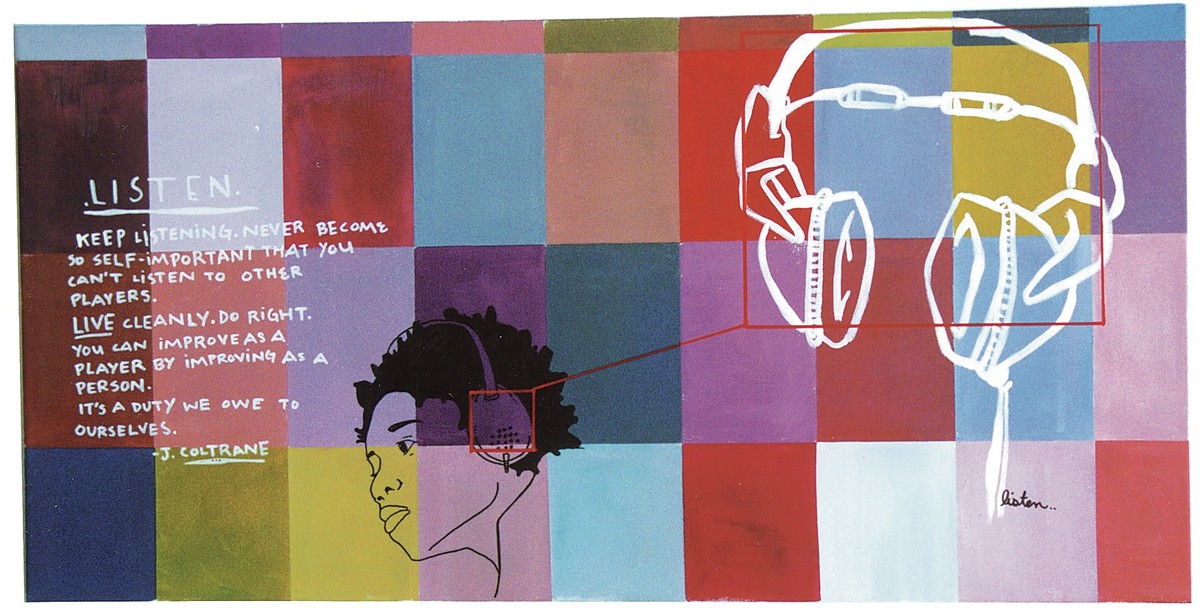

It's all down to critical listening. If you don't know what to listen for you won't hear what you need to do. Ever wonder why some musicians are better than others? Because they listen, and they listen well. A great musician usually hears their instrument for what it really is — pitch, timbre, timing and feel — plus they also hear the musicians around them and place their own contributions in ways that only make the music better as a whole. A lesser musician will be certain their pitch is right, because their finger is on the right fret, and that the tone is fine because it worked at the gig.

People who record music are the same way. You can have two people engineer the same music in the same room with the same gear and the recordings will be different. This is all down to how the recordist hears the music and sounds and how they respond with thousands of little changes that determine how the sounds get recorded. I've seen more experienced engineers come into my studio and make recordings that I doubt I could ever come close to — and it's humbling.

So how do we develop our critical listening skills? There's no simple answer. Comprehending the speakers that you use for recording is obviously the first step. Use a pair of speakers that allow you to hear the details of the sounds. I remember getting rid of my first monitors for a slightly better pair and being blown away by what I was missing. Every speaker upgrade since then has cost thousands of dollars and has yielded a slight increase in fidelity. Understanding what you hear when you listen to other folks' recordings is key. I listen to CDs all the time when I'm not recording, and even though I'm always trying to enjoy the music that's on them I also think about what's working and what's not working for me. Listening in the space you record at is also very important. I play many of my favorite and new CDs at the studio while setting up or doing non-recording tasks, and I listen closely to how they sound there as opposed to in my car or at home. Learn to pick out overdubs that have been buried in the depths of a busy mix. Analyze what instruments are doing what. Knowing what has worked in the past and what could be better is always a good starting point. Building on tried and true recording techniques is fine, but just remember to try and go further with every session. When tracking new material, listen for the quality of the sound. Yes, quality of sound is 'subjective' but listening for sounds that are pleasing, fit the material, and keep the music interesting is very important.

I was hired a while back to mix two very different home-recorded projects. One was poorly tracked, with little attention to the quality of the individual sounds. Drums were sometimes almost okay, until they decided to skip the snare mic since "there was enough in the overheads" and put in only under the snare. There were guitar tracks that just sounded ugly, with a nasty crackling overdrive (no, they didn't hit the converters too hard — I don't know how they did it) that made the tracks really unpleasant to listen to. When I asked about it they said they'd had a lot of trouble with getting sounds on occasion. The problem was they had given up, even when they recognized that sounds should be better. The kicker had to be the phone ringing on the chorus of the last song I mixed. It was a very frustrating project. The other session was also tracked at home, but much attention had been paid to the tracking. Sometimes the snare wasn't perfect, but I was able to help them EQ it enough or gate a nearby mic that added some crispness. But many of the tracks were recorded with enough care and foresight that elements of the songs fit together well and worked as a whole. We even finished early, though I left a list of things to edit, add and clean up!

The moral? You have to learn to listen. To really be able to hear what is happening when sounds come out of your speakers. There is no easy way to learn this — all I can do is tell you how utterly important it is that you do so.