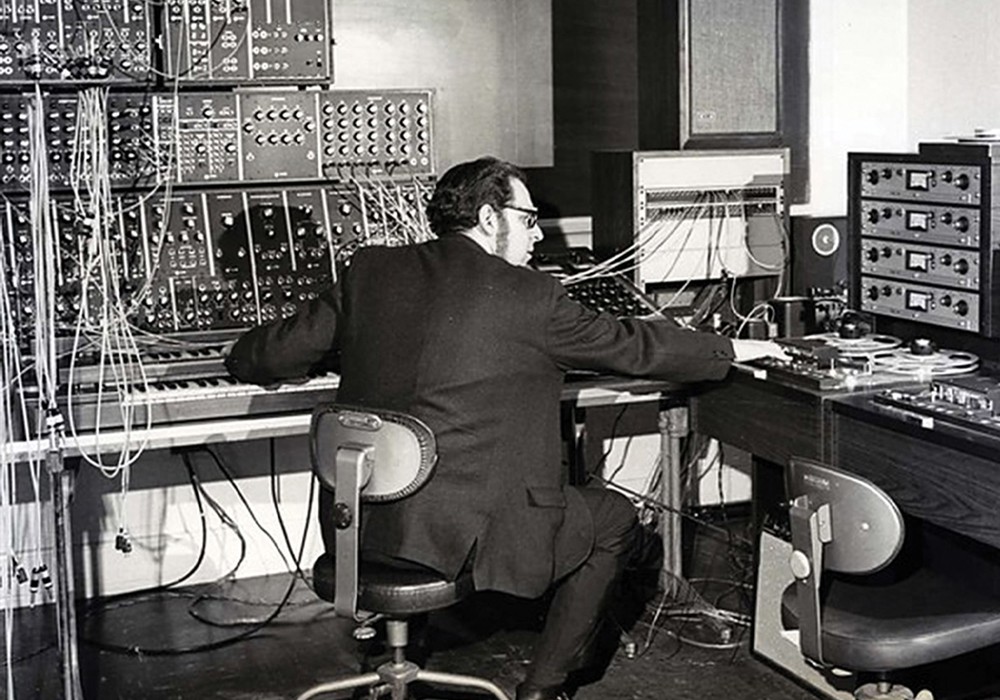

In an industry that has become more and more digitized, Nashville's Welcome to 1979 and its owner, Chris Mara, are offering clients an opportunity to step back in time. With a recent purchase of a vinyl cutting lathe, Chris, along with his vinyl mastering engineer Cameron Henry, is continuing the analog tradition, giving bands a chance to cut masters directly to vinyl. I talked with Chris and Cameron about what it's like learning a forgotten craft, and about the different ways Chris may be a leader in a resurging analog revolution.

You've had the lathe for a little while now?

Chris Mara: It was already restored when we got it, but it took a while to get it up and running.

I know you've been doing some mastering with the lathe, but you have been advertising cutting bands live to the lathe?

Cameron Henry: We've done it a few times. We did one as a trial to see what it sounded like, and it sounded so great that we thought, "We need to start doing this."

CM: The guy that restored it, Chris Muth (he designs Dangerous [Music] gear), knew I had a studio. He said, "The first chance you get, cut directly to it. It sounds phenomenal." I think we are the only studio in the country that can cut directly to disc.

CH: There are a couple of live venues and places that do it, like Jack White's [Third Man Records, Tape Op #82] in town does it.

CM: It's a live performance though.

CH: And it's private. It's not like you can book it.

Do you cut a whole record?

CH: It can be anything. Whatever the artist is comfortable with.

CM: I'm trying to get into the band's mindset that they could come in for a day and do an LP. An A and B side in a day; it's recorded, mixed, and mastered. It's really affordable and sounds awesome, and those two words usually aren't [used] in the same sentence.

CH: Yeah, we usually cut acetates [test lacquers]. Throughout the day the band will be rehearsing their LP side, or their single. Chris will be mixing upstairs; I'll be down here cutting acetates and, in between takes, I listen to what's going down to the disc. I make adjustments as we go. As the band is rehearsing, I'm rehearsing, and Chris is rehearsing, so at the end of the day everybody's on and it's all dialed in.

Everybody's laying it down, all together?

CM: They have to.

CH: There're no overdubs. The sequence of the songs has to be performed live. You can't stop, so they have to get through every song in a way that doesn't have mistakes, or the whole side has to be started over.

CM: We encourage them to rehearse side A and rehearse side B separately. We're talking to bands about coming in for a weekend, working one day on side A, and one day on side B. We're gonna take a mult from the console and record it to Pro Tools so we can listen to it, because we can't listen back to our master. We record straight to the disc. The band comes up, we listen to the take on Pro Tools; once we get one we like we label it and then do another pass as an alternate.

CH: As a safety backup, in case there's some manufacturing problem.

CM: So we've got another ready to go. They'll come out of here with two versions of it.

How long did it take you guys to learn this?

CH: We were somewhat in a vacuum, but we had some mentorship. Chris and I both tracked a lot of records that came out on vinyl, but we didn't cut the masters. So we had the masters, either digital or tape recordings, and the finished product. We could put the masters on and cut our version of those records, and then see how we sized up to whatever the other guy did. We learned backwards that way. We figured out people's processes by analyzing their work.

Reverse engineering.

CH: Exactly.

CM: A gentleman by the name of Hank Williams offered us his time. He owns MasterMix and he used to cut on a daily basis. He came over, and it was like a Karate Kid movie. We spent an entire day without even turning [the lathe] on, and instead talked about what we were going to do tomorrow. He spent a week with us; then he let us go play and we fucked it all up. Then he came back and got...