Back in 2000, while on a session break, I got a call at the studio. It was a friendly voice with a subtle New York accent.

"Zippah Studio..."

"Hello, I'm trying to reach Pete Weiss."

"That's me," I said.

"That's me too. I just searched for myself on the Internet and ran across your website. I was a recording engineer a while ago and I see that you are too. I figured I'd give you a call and see how business was going!"

The elder Pete had retired from recording engineering right around the time I took my first steps into that world. For many years, our Discogs.com production/engineering credits were accidentally merged (along with a THIRD Pete Weiss, the drummer from Thelonious Monster), making it look like there was a guy named Pete Weiss who had a shockingly long, steady, and weirdly eclectic career. The credits have since (mostly) been fixed, but at the time, anyone stumbling onto our listing would see a guy who apparently worked with everyone from Barbra Streisand to Chris Brokaw to Bill Evans to Bell X1 to Looking Glass ("Brandy") to Willard Grant Conspiracy to Red Hot Chili Peppers, etc.

We had a nice chat. He had been very active as house engineer for Columbia Records, among others, in the 1960s and '70s before going freelance for a while in the early '80s and eventually changing his career path to tech and science writing/editing later in that decade. Pete and I found it interesting that, while we did a lot of the same things in the studio — mic placement, gear maintenance, session management, etc. — we had each taken different paths in our work. In the 60s and 70s, he had been employed by labels and studios in New York, whereas I took a more independent path, operating a fairly small but high quality indie studio in Boston, and eventually opening a larger, retreat-type studio in rural Vermont.

He struck me as a very balanced, even-keeled guy — I was happy to hear from him. After our initial phone chat, we managed to stay in casual touch, dropping a "how's it going?" email to each other now and then.

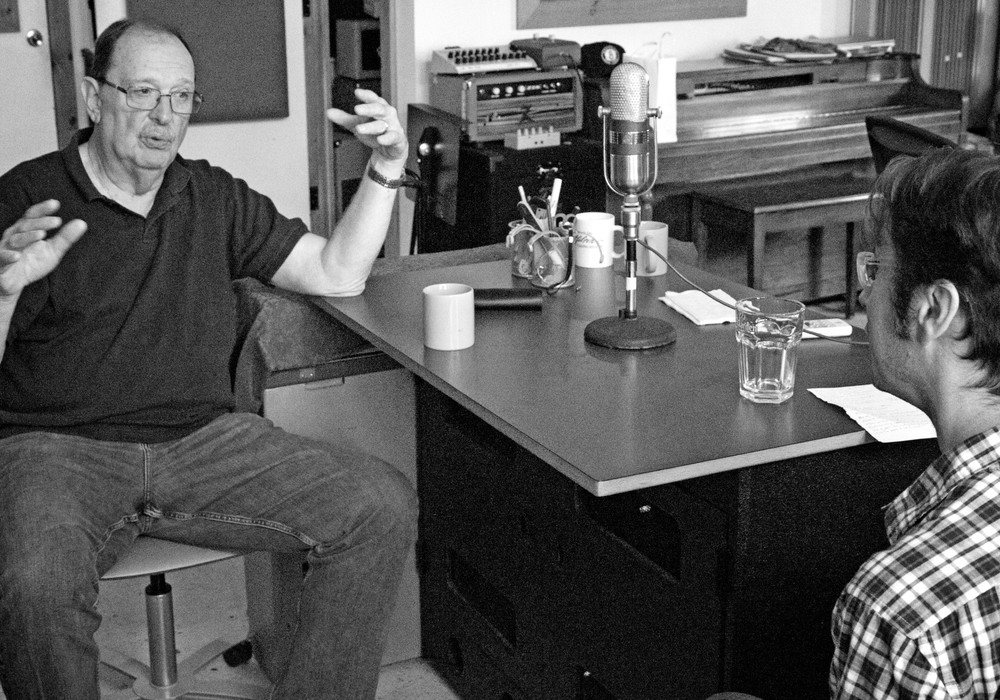

Finally, in late 2014, I got to meet "the elder" Pete Weiss in person. I was going to be in New York for a mastering session, so I arranged to go a day early and meet with Pete in Williamsburg, Brooklyn at Cowboy Technical Services, a studio run by Eric "Roscoe" Ambel and Tim Hatfield. Eric and Tim were on hand for the interview, and I'm glad of it — not only were they lovely hosts, they also chimed in with some great insight, questions, and stories of their own. We had a nice few hours, chatting about the ever-changing New York studio scene of the 60s, the birth of the EV RE-20 microphone, marijuana, Max Weinberg's early years, how the recording industry itself has changed over the past 50 years, and of course rock's Zelig, Al Kooper.

(For this article, I'll refer to the elder (born in 1945) Pete Weiss as "PW1" and will call myself (born in 1966) "PW2." We are not related, that we know of.)

PW2: So, you were active for 18 years, you said...

PW1: Approximately, yeah. From about '65 to '83.

PW2: Eric was saying that his band did an album at Columbia in '82, right?

EA: Well, when it was A&R, on Seventh Avenue.

PW1: Oh right yeah, that was Studio A1.

EA: Former Columbia room.

PW1: Yup.

EA: In '83. That was back when they had those, like, you know before answering machines and all of that stuff? They had this thing, Radio Registry. And these phones were like hotline phones. And the session guys would call in, you know, this is Eric, what've you got? And they would send him to the next session.

PW2: Oh, really?

EA: Yeah!

PW1: Yeah, almost every serious studio in Manhattan had a direct line to Radio Registry, 'cause that's where all the musicians got their gigs. There was no email, no cell phones, nothing back then. We're talkin', you know, pretty primitive stuff. And there was a restaurant on West 55th Street, it was originally called Jim and Andy's. One of two partners died, and then it became The Possible Twenty. Which is a phrase that the people that book musicians for jingle dates used. It's an hour with a possible twenty overtime. So the place was taken over by musicians who used to hang out there when it was Jim and Andy's. And every couple tables there was a direct line to Radio Registry. In the actual restaurant and bar.

EA: Yeah, these were like — literally, they looked like a hotline phone...

PW1: Yeah, just a handset, no dial...

PW2: Just a direct line. I had never heard about that, that's really cool. So, you could be on call, if you wanted to be?

PW1: Oh, everybody was on call. These studio guys back then, they were gunslingers. You know, there were guys who would get hired based on their reputation. Very often, especially for R&B dates, if you saw one guy from the rhythm section walk in, you already knew who the other players were gonna be. They moved in these groups.

PW2: Yeah... Yeah. Well, I mean, this is a blanket statement — but it sure seems that the musicianship in general was better a certain time ago. For a lot of my sessions, I find I'm doing a lot of damage control. [laughter from PW1] Turd polishing, or whatever. Fixing.

PW1: Turning up the talent? There's no fader marked talent, right?

EA: Yeah, and well, nowadays, I mean, everybody's got an MBox, like they know that they could jump up there and fix that bit, or something. Like, the bass player that makes one mistake, he's not even thinking about punching it in. Because right under that take is a better note. But — you know what really blows my mind? When I was a young guy, anybody that said they were from Berklee, I just went the other way, because they were all like, so like, Fusak [fusion Musak? -ed.], and they weren't playing the song. Their playing... it was like weightlifting. And that whole Berklee thing, like in the last ten years, I mean, I've seen some really great people. And I mean, creative, and not just playing, super playing, like, they're really song players.

PW2: Well, the new president of Berklee is apparently more like an anthropologist than like a... jazz... chops... guy. You know? I have a few friends that work there, and my understanding is that the guy has really pushed a combination of liberal arts with more of a songwriting kind of bigger picture sort of thing. And a lot of world music too, from what I understand. So maybe that's what you're hearing. That influence.

PW1: My former colleague, Don Puluse, who used to head up the production department up there, they had a studio, and Al Kooper taught there for a while — you know who Al Kooper is?

...

_display_horizontal.jpg)