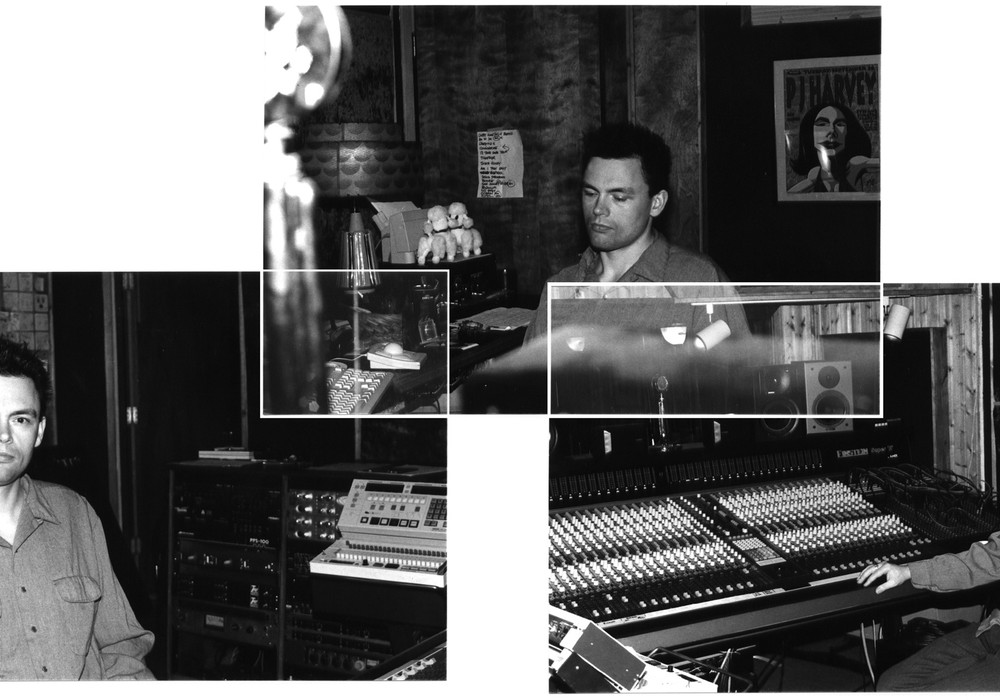

I've seen Gareth Jones' name on records since the '80s and have always wanted to meet him. My imagination created a stuffy, meticulous character; an engineer/producer driven by a need for electronic perfection and a slave to the technology of recording. This is the man who engineered albums by Depeche Mode, Erasure, John Foxx, Einstürzende Neubauten, Nitzer Ebb, and Wire, and made them propulsive, fresh, and new sounding. Little did I expect to meet up with an incredibly passionate, thoughtful, and friendly bike riding gentleman with whom I felt an immediate connection. Gareth has kept busy over the years, working with groups like Interpol and Grizzly Bear, and current work that even includes a New Order remix. We met at his studio, Strongroom, in London's Shoreditch neighborhood, not far from where his career initially took off at The Garden Studio with John Foxx, where we had a wonderful chat and a lovely lunch at the Strongroom Bar.

You've had a pretty fun career.

I've had an amazingly fun career.

I didn't know about your Pathway Studios connection early on. That place was churning out some interesting underground records in that era.

It was amazing. Mike Finesilver was the one who gave me a break, which was fantastic. He was really one of my first mentors. I'm like a gifted amateur, in the sense that I never had the privilege or pleasure of studying as an assistant under a great master. Most of my mentors have been musicians. I've learned a hell of a lot from bands, as well as all the incredibly creative colleagues I've worked with. Mike gave me a bit of a break. He said something great to me, as well. He told me, "Don't worry about this." [He said that] because I was thrown into the 8-track world, by myself, with no assistant. He said, "Okay, go." I'd done a bit of recording on my own at home, and had had basic training at the BBC, so I knew a little bit about signal flow. It seems ridiculous, looking back — I didn't know shit. But I felt I knew a little bit, like lining tape machines up. He really underlined the importance of getting on with the bands. He said, "The great engineers are geniuses at their audio work. Plus, they get on with the band." Obviously 90 percent of it is facilitating a situation for the band where they can flow. I was always obsessed with trying to do the best headphone mixes I could, making a creative and comfortable atmosphere for people, while I was really winging it. I'm forever thankful to Mike for giving me that break. Pathway was pretty cool, because we did loads of demo work. It was like a cheap-ish 8-track analog studio. Also, there was a lot of records that came out of there from the punk times. It was a great starting point for me, because there was a real mixture between demo work — where I had to learn as much as I could, as fast as possible, and still do a good job for people — and the challenge of actually working with people who'd perhaps made two or three albums already and were in there to make a real record. One of the great things about Pathway was that it was homebuilt. Barry Farmer was one of the previous engineers who had built the console and an echo plate. We had an echo plate, which was an unfeasibly expensive thing. I'd probably love it if I had it now. I still like spring reverbs. I've got tons of springs hooked up for my modular synths. Guitar amp springs, Fender springs, Ampeg springs. They're still readily available, and cheap. Back then, there were no other spatial effects in there, apart from three 1/4-inch tape recorders: one to master onto and two as delays.

You had to be creative.

Certainly you must have started with 8-track, or 4-track, or something?

2-track, 4-track.

So you know all about building sounds and committing the whole sounds to track.

Mix the drums to a track.

Exactly. That's a different world. I've been working in Woodstock with a super nice guy, Christopher Bono, who's become a friend. We were working on his project, called Ghost Against Ghost. It was huge, like lots of these projects are. He was stemming it himself, and I went over to help him finish the stems. One of the things we did was stem the drums down to stereo. It was wonderful. It reminded me of the start of my career. Not quite to one track, but to two tracks. I finished up using the stereo drum stems on both mixes, so it's nice.