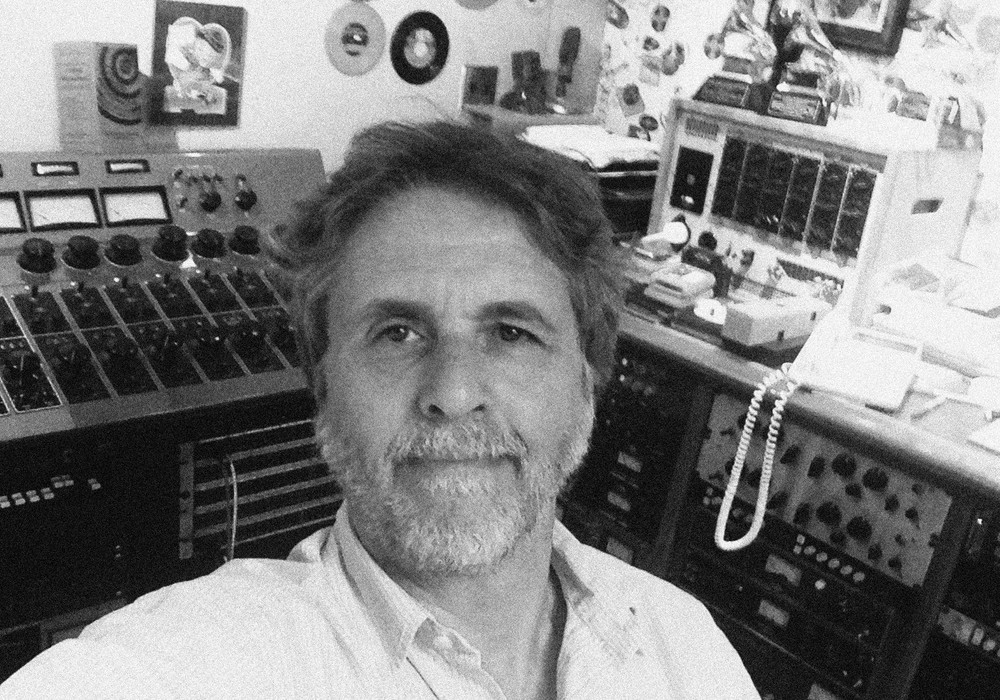

Mastering engineer Gavin Lurssen has been behind the console since 1991, won three Grammys and one Latin Grammy, and runs Lurssen Mastering — one of Southern California's busiest facilities. He's worked on records like Robert Plant and Alison Krauss' Raising Sand and the Foo Fighters' Sonic Highways, as well as with clients like Ben Harper, Queens Of The Stone Age, Eric Clapton, Miranda Lambert, Rickie Lee Jones, and Elvis Costello. The fascinating Lurssen Mastering Console app/plug-in recently came out, via IK Multimedia, and was developed with Gavin and Reuben Cohen of Lurssen.

How much of a lead time do people give you as a mastering engineer?

You know, in the early days when I started out this whole thing, it was in '91. There was always a production coordinator. People would book the mastering session about six weeks ahead. Sometimes three months ahead. Nowadays, they get finished with the record, book the mastering, and expect you to be available instantly.

I see that all the time. Especially with independent bands or artist-financed projects.

We figured out a way to do it though. You get together, gather the team and say, "This is the game we're playing, this is the field we're on. How are we going to make this work?" Then we do it.

What kinds of things have you implemented in order to have faster turnaround?

Well, it's how fast, how affordable, and how good. The "how good" thing is covered, because of what we do. The "how affordable" angle is how do we figure out how to make the rate, just to pay our bills? Really, we're not getting rich. At the end of the day, when you add up rent, the employee costs, taxes, and all the things that add up to make your overhead, your goal is to make at least that number. Then it's "how fast," which is what you asked about. Because we're all analog, it's not as simple as opening a file, doing some tweak, running an export, and you're done — although that is the expectation of (all) the younger generations coming into the business. They have it in their mind that this is the way to do recording, mixing, and mastering. It takes communication between the person in the mastering room (where you put up the file, convert it to the analog, put it through the board, make some tweaks, re-record it to digital) and your production guy. He's working on that while you're working on the next thing (that somebody wants). It's really like a chain of events. You've got one person working in the room — or maybe two — and another person working in the production department. Then there's someone who's communicating with everybody. Sometimes the communication is, "I have no further updates" which tells them that we're still in a holding pattern while we're working on this. That's very important communication. The communication is as important as everything else. If they want something super quick, they will feel secure if they get communication about it. You could sit there and say, "It's not ready yet" and then get into some discussion about why it's not ready; but if you constantly communicate and update, they can see that you're working on it.

What is the production department, just so our readers understand the process?

When we are in the mastering room, it's all analog. The tape, or the digital file, gets converted so that we can do our processing in the analog domain. One hundred percent of what we do has been done that way. It does slow things down a bit, although we've developed our system. When we record it back to digital, we have a raw file. That file needs to be scoured for any little tics and clicks because, in today's world, most of what comes in needs cleaning up. Very rarely, if ever, does it happen here that we add tics and pops, because we pay such close attention to our clocking and all that. But in the mix environment, particularly in the new generations of people who are working with plug-ins and all that, all kinds of clocking issues can happen. You're also in an environment where it's so revealing, and they've come from an environment of working on headphones in a bedroom somewhere. We start to hear all this stuff that people haven't heard. The music has to be scoured for that. We have some digital tools that can clean that up. Then we have to make it all faded and nice. We have to then go through sample-rate conversion. If we can, we like to work in high-res, so we master and record a high-res file and then everything else gets made from...