More than two years after his passing at age 94, Pete Seeger's legacy only continues to grow. For seven decades he was living proof of the power of song. But how did Richard Barone, an indie rocker best known for his post-punk power pop, come to co-produce the final single of a folk legend and national treasure? We find out here, in Richard's own words.

One of my early childhood memories is sitting in front of my folks' big RCA color TV watching the Smothers Brothers Comedy Hour, before it was famously cancelled by CBS because of the brothers' liberal views. There I was, watching a skinny, joyful, incredibly determined and earnest-looking dude singing "Bring 'Em Home" to an enraptured young audience. It was the height of the Viet Nam war, and I was too young to understand that the singer had been blacklisted for years, or that his name was Pete Seeger. But I felt the emotional pull of the words and music, thinking of my older brother and cousins who talked about the draft and how to avoid it, and I never forgot the experience of watching that man sing that simple plea. A big fast-forward to 2010, and a lot had changed. But there were still plenty of wars going on, and there were still reasons to sing out.

One night, while attending a show at my home venue, New York's City Winery, the booking manager pulled me aside and asked if I would be interested in hosting and producing a benefit concert aimed at raising funds to help local cleanup efforts down south.

The BP Deepwater Horizon oil spill was an environmental disaster few could fathom. Set off by an explosion on April 20, 2010, the underwater well spewed 1,000 to 5,000 barrels of oil per day into the Gulf of Mexico over 87 days — a total of 210 million gallons — until it was supposedly contained five months later. Relief was slow in coming for local residents and businesses mired in the muck, and wildlife and tourist trade were devastated.

Even if I hadn't been born and raised in the Gulf region, I would have agreed to help produce the event. The only question was, "Who I should ask to perform and speak?" I knew we needed artists who would resonate with the cause, get the message out, and sell tickets. That very night, still at the venue, I bumped into my friend, journalist and publicist Rhonda Markowitz. When I told her about the concert plans, she dryly said, "Get Pete Seeger."

A big part of Pete Seeger's past of course, was his legendary cleanup of the Hudson River. For decades the river served as a garbage dump for industrial refuse. The Clearwater Foundation and Festival in upstate New York, and the clean river itself, are everlasting reminders of his efforts.

So, yes... Pete Seeger. But how do I reach him?

"I have his home phone number," Rhonda offered. This is why I love publicists.

I had met Pete once before, at a memorial service for our mutual friend, Joyce Wein, wife and partner of Newport Folk Festival producer George Wein. Although Pete performed at the service, he had lost his voice, and almost silently led everyone in a haunting sing-along of his song "Turn, Turn, Turn." I was genuinely moved, but when I told him that after the service he apologized for not being able to sing. Now, a few years later, I had my concerns as to whether he would be up to performing. Regardless, the next day I took a deep breath, picked up the phone, and dialed the number.

"Hi, this is Richard Barone. I'm calling for Pete Seeger."

"This is Pete."

"Hi, Mr. Seeger. We met a couple years ago at Joyce Wein's memorial. We spoke after."

"Yes..."

"Well, I'm producing a benefit concert to raise funds and help local residents clean up from that terrible oil spill down south..."

"Ah, yes. I'm glad to hear this," Pete replied, energized. "My collaborator, Lorre Wyatt, and I just finished a song about it."

"Wow, really? About the spill?" "Yes, let me sing it for you."

Pete then proceeded to sing all seven verses of "God's Counting on Me, God's Counting on You" over the phone, a cappella, as I sat at my kitchen table, astounded. At 91 years old, his voice was weathered, of course, but still tuneful and with his trademark purity. The song was vintage Pete; a great folky tune, full of sweet and funny one-liners, and current political references. I flashed back for a second to sitting on my parents' floor, watching him on TV.

"Wow! Have you recorded it yet?"

"Well no, we just wrote it."

"Why don't we record it?" I offered. "I'll produce it for you."

Pete seemed excited about the idea, and that's how it all started. But first, of course, we had to stage the "Reclaim the Gulf" concert — which turned out to be very successful, swarming with reporters from CNN and Rolling Stone. I had asked several other artists to perform; each brilliant and each in awe to be on the same bill as Pete, myself included. R.E.M. vocalist Michael Stipe even sent in a label design for a special wine that was sold as part of the benefit.

Pete wanted to go on early in the show. While he got around pretty well for his age, it was still not particularly easy to coordinate getting him onto the stage. His thoughtful daughter, Tinya, was in constant communication with me along his drive into the city to make sure he was properly taken care of. Once arrived, Pete was terrific, bringing his small entourage from Beacon, New York, including a Native American combo to open the show that included his friend of over 40 years, Roland Mousaa. Pete allowed me to pick which media folks he would speak to, graciously granting them interviews. When he took the stage he performed a short, captivating set and, in his trademark way, got the entire audience to sing along. But, already, my focus was getting him into the studio.

I wanted to know every detail and nuance of Pete's musical legacy before we recorded. First, I re-watched the excellent 2007 PBS documentary Pete Seeger: The Power of Song, hanging on every word. Then, I combed my local thrift shops for vinyl copies of albums by his old group, The Weavers, as well as Pete's solo releases. I found them and listened to them over and over.

That's when it hit me: the responsibility of delivering a recording that would be true to the man and the legend. Visions of Pete hopping freight trains with Woody Guthrie; Pete standing up to Congress during the McCarthy era, facing conviction and jail time; and Pete bringing "We Shall Overcome" to Dr. King. These images filled my thoughts. Everyone knows that Pete had pretty much singlehandedly spearheaded the American folk revival, while composing many of its most famous songs. Peter, Paul & Mary, Bob Dylan, The Kingston Trio, The Byrds, and countless others owed him an incredible debt, one that Pete was too humble ever to admit. I didn't want to let the man down.

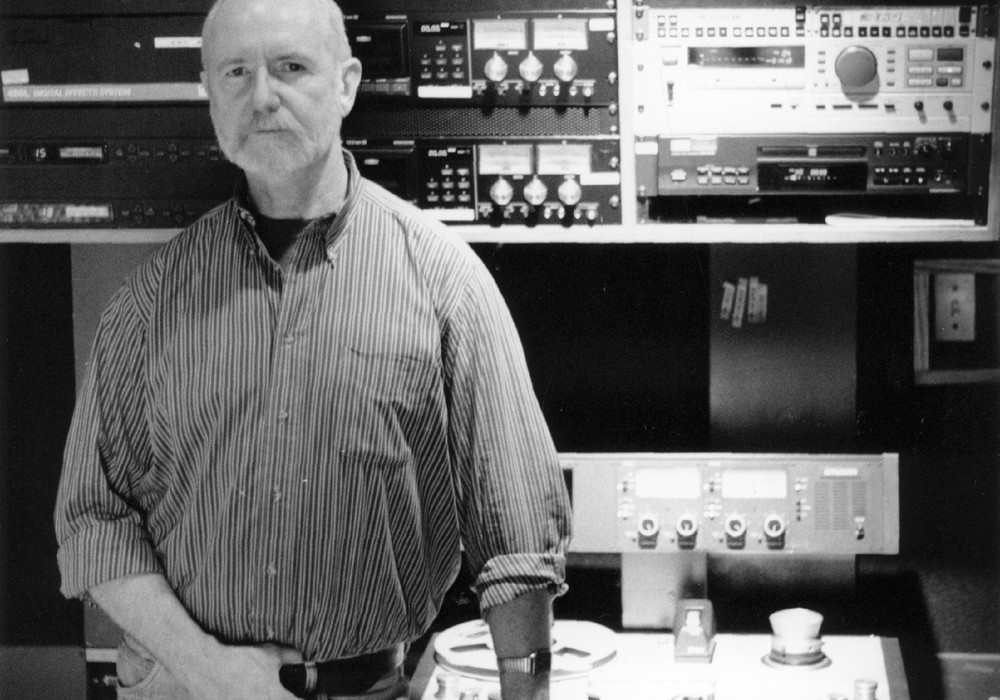

I called my friend and recording engineer Matthew Billy to record, mix, and co-produce the session with me. Besides being an excellent engineer, I knew Matthew was a huge, respectful fan of Pete's. He and I had already collaborated a lot, and this would be something really special for both of us. For the next few weeks Pete called me nearly every day to talk about the session. It may be hard to imagine, but sometimes he'd call at any hour of the day or evening, his energy and enthusiasm reminding me of a 17-year-old kid.

"Richard, can you make me a hit record?" he asked one afternoon, adding, "I've never had one." Pause.

"Pete, you have had so many hit records. Do you want me to list them for you? I have them here."

"No, I've never had a hit under my own name."

"What about 'Little Boxes' [Pete's 1963 hit]?"

"Yes, but I didn't write that."

Another pause. Okay, I kind of understood what he meant. And if anyone in the world deserved to have a hit record, it was Pete. But knowing what constituted a hit record in the Max Martin/Dr. Luke-dominated year of 2010, I took another deep breath.

"Pete, I will do everything I possibly can to make you a hit record."

I was serious. I would do anything for him. Pete told me a lot about his co-writer Lorre Wyatt, who he wanted to perform on the recording and sing harmony. Lorre had suffered a stroke and it took nearly a decade for him to re-learn how to speak, sing, and play music. Pete wanted to make sure I understood this, and that he wanted to feature Lorre prominently on the recording. He also wanted to invite others from the Sloop Club to sing along as they did on their monthly song circles.

I told Pete I'd like to use my RCA 77 ribbon mic from the 1940s for his lead vocal. He liked that idea. "Oh, and Richard, what kind of beat will we have?" He startled me by asking about the beat. Matthew chuckled when I told him. We didn't think folk singers thought like that. But he was so fully engaged in every detail. Sometimes he would forget some of the details though, and I'd have to remind him. "Don't worry, Pete. I'll remember for both of us," I'd say. "That's my job." After a pause he would add, "Richard, I don't have Alzheimer's, but I have some- heimers," which would make us both laugh. Pete had a hearty, engagingly honest laugh. Over those several weeks, these kinds of conversations made me feel like we were becoming good friends.

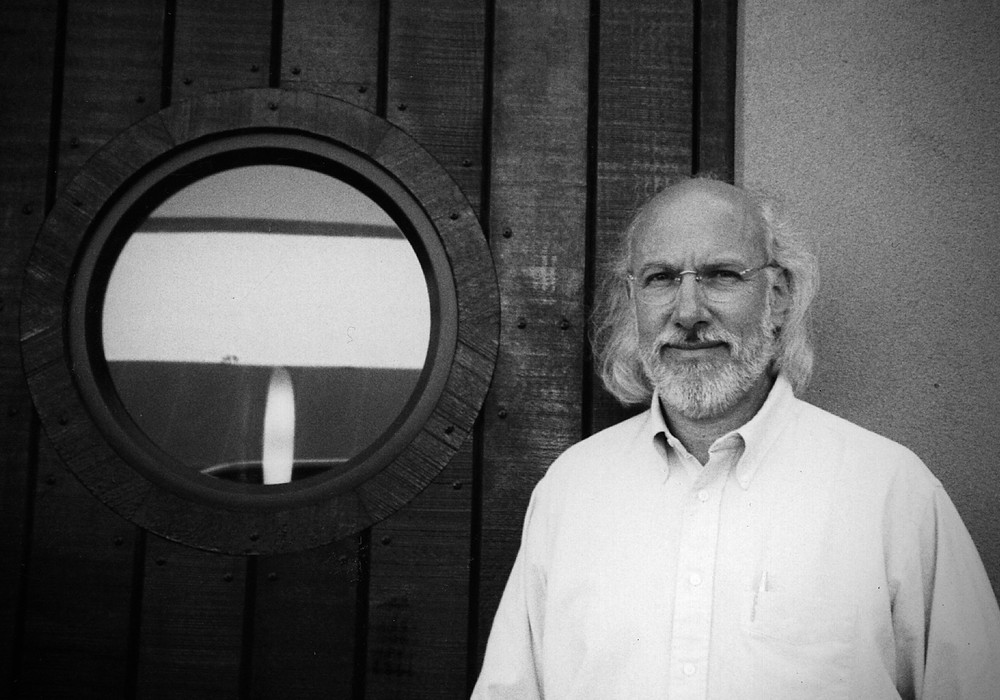

Roland Mousaa, up in Beacon, became invaluable in coordinating the scheduling. August 21st would be the day for recording, the location somewhere near Pete's home ("67 miles north of the City," Pete was fond of reminding us), so he wouldn't have far to travel. Pete had purchased the 17-acre plot in 1949 for just $1,700, as he was proud to say.

In our frequent conversations, Lorre Wyatt also gave me a lot of essential information about working with Pete, such as the important issue of what time of day his voice and energy were at their strongest. That would be at 9 a.m., certainly the earliest in the day I had ever recorded anything!

I came up with three simple points that guided the project:

1. The quality of the recording had to be the absolute best we could create, as clear, crisp, and articulated as Pete himself. It had to have a classic folk feel that his older fans expected, yet be in the moment and lively. i.e., it had to sound both familiar and new.

2. It had to all be done in a timely fashion, for immediate release while the spill was still in the news.

3. We needed to film the session professionally, in order for a video to reach the most people. Although there were many live clips of Pete, few, if any, were actually produced as music videos. I knew we needed to call in the best videographer. I had known Damien Drake from his work with VH-1 and other networks, and I knew he had the vision, personality, and talent to do something amazing. I was thrilled when he was available and interested.

It occurred to me that it might be beneficial to have a special guest vocalist on the record. I suggested to both Pete and his label, Appleseed Records, a few names such as Bruce Springsteen, Buffy Sainte-Marie, and Joan Baez. Pete pondered, then asked me to contact Billy Bragg in England and ask him to be on the recording, which I did, and who absolutely agreed. But a few days later Pete called and said he had a change of heart and wanted only his inner circle of close friends from the Sloop Club singing on the track. "I want 'real people,'" he said, not condescendingly, but meaning he did not want to invite people based on their marquee value. I told him I understood. But from conversations with Appleseed Records, in which I mentioned the idea, I could tell that, unlike Pete, the label was definitely interested in having additional star power.

At this point I was picturing us setting up shop in a nice, clean, controllable recording studio with a rhythm section, isolation for the drums, and backing singers on hand. Pete would be in a nice, quiet vocal booth with my RCA 77. Matthew and I would be in comfy studio chairs. I had been inquiring for availabilities of studios in the general vicinity of Beacon (and as far as Woodstock), had made calls to musicians, and was thinking about who to put where in the studio when the name "Pete Seeger" appeared on my iPhone screen.

"Hello, Richard? I've been thinking, and I want to record on the boat."

"The boat?"

"The Clearwater."

Pause. In the seconds before I replied, all the reasons why this would be a challenge came flashing before me: the wind, the noise of the rigging, the waves, the lack of electricity, the uncontrolled ambience. But I also thought about why it was the perfect place to record: The Hudson River Sloop Clearwater is the most striking symbol of environmental grassroots action we could hope for, and exactly what Pete's song was about.

"Pete, of course. Great idea."

"But Richard, can we do it," he asked, "while sailing?"

"Pete, we can do anything," I blurted.

This is my favorite reply to have for an artist, ever since Tony Visconti told me this once in a studio session. But I hoped I was right. But, honestly, I wasn't sure. After hanging up with Pete, I called Matthew and told him the sobering news. With a short time to go, we would be recording Pete and his colorful friends, including Lorre Wyatt, Roland and his wife, Mindy Fradkin (a.k.a. Princess Wow), and others on the tight deck of the Sloop. All of this would take place while sailing up and down the Hudson River, disembarking from the Beacon dock at 9 a.m. Along with my concerns about the wind and noise, Matthew brought up the very valid question of a reliable power supply.

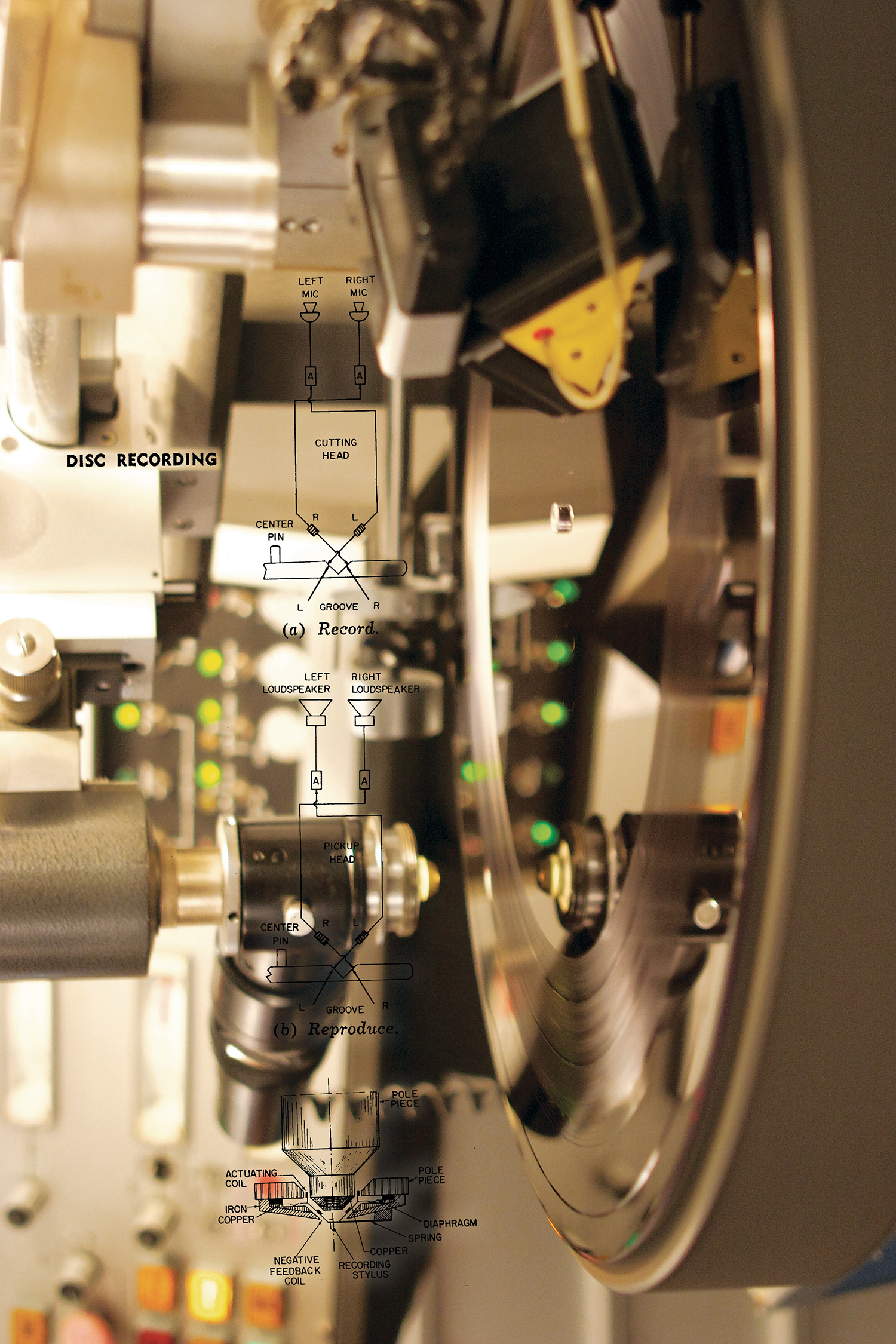

It took several phone calls to work out getting a portable power generator onto the sloop. Once we had that, Matthew took inventory of what he needed to record with: a MacBook Pro running Pro Tools, a battery- powered mixer, and some good mics. We wouldn't have access to the boat beforehand to see where we could set up, so it would all have to happen on the morning of the session.

To make sure we were ready to start on time we would arrive the night before, staying at Roland and Mindy's house in Beacon. On the warm summer evening of August 20th we took the Metro North train from Grand Central Station, lugging our gear and my vintage 1955 Gibson LG-1 acoustic guitar strapped to my back. (How could I not play along?) At Roland and Mindy's we saw Roland's large psychedelic paintings, as well as his patented solar and wind power inventions, and we heard his stories of working with Pete all those years. Princess Wow showed us her outrageous hat creations and baked us cookies from vintage recipes. Already this was turning into an amazing experience, but one thing was clear: anything could happen.

Early in the morning we headed out to meet Pete and Lorre at the boathouse, where we would rehearse the song. Upon entering, I was happy to spot a portrait of John Lennon hanging on the boathouse wall, which I took as a good sign. Damien and his second cameraman were already there to film us arriving and setting up. You can see the look of concern on my face in the video. How were we going to pull this off?

As a safety, once the banjo was suitably tuned (trying to help with my digital tuner, Pete snapped, "You're making it WORSE!"), Matthew would record everything as Pete and Lorre performed the song once or twice through. It was a relief to know we had at least a complete take, and several segments in the can, before we set sail.

Then we all boarded the sloop Clearwater. Watching Pete walk the length of the Beacon pier to the boat, wearing a shirt he told me his wife, Toshi, had given him in 1967, wearing his banjo in its gig bag strapped to his back, was simply, well, legendary.

Once on the boat's cramped mid-deck, Matthew quickly set up and found a stable place for the mic stands. The crew got ready to set sail, with everybody pitching in, especially Pete, pulling the rigging and hoisting the sails. All of that onboard activity made for perfect imagery in the video, illustrating Pete's lyrics about working together to achieve a goal.

It was a crisp, late summer morning on the Hudson, a bright foreshadowing of fall. The crew leader talked about the history of the vessel and of recent repairs to the ship's hull. The primary purpose of these scheduled sailings is education, so while the apparently impromptu performance that day came as a surprise to most everyone on board, group singing was to be expected, and songs like Lorre Wyatt's "Sonos el Barcos (We Are the Boat)," which Pete had also sung to me in English and Spanish on the phone in weeks prior, were great warm-ups as we set sail. Everyone sang.

When we were fully underway, Pete began to lead a practice of "God's Counting..." with the singers onboard. Most already knew the song, having sung it with Pete at their monthly Sloop Club gatherings. Cameras rolled.

Soon, we were ready to hit "record." Matthew nodded to Pete, who cleared his throat and spoke into the mic, "There will be a human race here in a few hundred years IF you and I work together in some way, and find a way to teach others to work together."

Now we had our intro to the song.

Pete and Lorre then led everyone on the boat through the seven verses of the song straight though, featuring one banjo and two acoustic guitars, as well as some random percussion we handed out. The music ebbed and flowed like the Sloop itself, picking up steam, sailing along. It was all done in one take, heading south on the Hudson in the direction of New York City. Pete shined, as he threw in some ad libs and comments. Now we had more pieces to use, full of Pete's personality and wisdom.

After we got the take, there were some random jam sessions on the boat, all filmed by Damien. Pete was in great spirits. In a quiet moment, he asked me to come down below to the cabin to talk privately. Pete asked me if Matthew and I had arranged everything for the session and filming ourselves, or if we had help, such as a label's support. He knew it hadn't been easy to organize it so quickly. "No, it was just us," I said. That's when he graciously decided to allow us to release the single on our own label imprint, which we later formed expressly for the project. Pete's regular label, Appleseed, agreed. As we were docking, Pete broke into a final, joyful impromptu jam of Lorre's "Sailin' Up, Sailing Down," throwing in some beautifully bluesy banjo solos, which you can watch on YouTube. It was the perfect ending to a perfect sail.

Once ashore, we said goodbye to Pete and crew and hitched a ride with Damien back to the city. We knew we had what we needed, but Matthew would have his work cut out for him putting together a seamless basic track. A couple of weeks later, we were both very pleased with the result. We planned to book studio time at Shelter Island Sound in NYC to overdub a rhythm section, as well as more instrumentation and a vocal chorus. First, I mailed a CD-R of the basic track to Pete at his post office box in Beacon, and waited for his response. Finally, after more than a week, his name popped on my caller ID.

"Richard, I'd like to play some different notes on the banjo. Can you boys come back up here?"

Of course. Whatever Pete wanted.

"Sure, Pete." And we scheduled a return visit, this time to Pete's house.

Matthew and I loaded up a rented Zipcar and made the trek back north, up the famous 67 miles to Beacon, then driving up the mountain to Pete's heavily wooded property with its 180-degree, unobstructed panoramic views of the Hudson River. There we saw the log cabin that Pete and his wife Toshi had built themselves in 1949, now inhabited by their daughter Tinya. Facing it was the large main house, modern and bright in design, with solar panels. We were welcomed by Toshi, who was busy in the kitchen. She took one look at our gear, smiled, and gently rolled her eyes. "More musicians," she seemed to be thinking.

How many times had musicians lugging equipment and microphones come through her door in 70 years of marriage to Pete? "You boys can set up over there," she said, pointing to a section of the living room. Weathered banjos and other instruments hung on the walls. The early afternoon sun was blasting in through the large windows and, looking around, I was filled with a sense of magic and history. Yet, it was clearly a household existing in the moment, not a museum of past accomplishments. No Weavers photos on the walls (well, maybe one small one), no awards displayed, no memorabilia of any kind. The room was flooded with the light of the present, and the kitchen filled with fresh local produce for cooking.

Matthew set up a workstation for himself and positioned a chair for Pete with a couple of mics while Pete was on a phone call. He was an engaged in a conversation, talking animatedly about his German heritage. Hearing him on the phone, I was struck by how accessible and genuinely friendly he was, and how rare those characteristics are among those with his level of fame. Wearing jeans and a Clearwater Festival t-shirt, again in great spirits, he greeted us ready to make music. With his banjo — famously inscribed "This Machine Surrounds Hate and Forces it to Surrender," a phrase echoing Woody Guthrie's guitar with its "This Machine Kills Fascists" inscription — he showed us the notes he wanted to change, very subtly different than what we had already tracked. We made all the adjustments he wanted. But, for me, this session was mostly a great excuse to spend some more time with Pete, soak in his wisdom, and just be in his presence. We talked more about what instrumentation we would add in the studio, as well as what we wanted for the look of the video. Telling Pete how many people he could reach on YouTube, with more than a billion users a month, he replied with a smile and chuckled, "Oh, my goodness." Matthew and I knew Pete saw it as both a fad (how many fads had he seen in 91 years?), but at the same time he seemed to realize that it was a great way to broadcast his message. The video became a big part of the project for him. We showed him our plans for a Pete Seeger YouTube Channel, compiling his vintage and recent clips we were making. By the time the sun began to set on the Hudson, we were on our way home, feeling we had a great, Pete-approved track to work with.

As soon as we were satisfied with the edited track we mapped out a verse-by-verse plan for overdubs. With seven verses to work with, we knew we wanted the arrangement to help tell the story, and we needed to put together a rhythm section that would be able to pick up the vibe and roll with the ebb and flow of a take that was recorded primarily on a sailing ship. We booked one overdub session with engineer Steve Addabbo. For the drummer we picked Steve Holley, who I had worked with many times and is one of the most versatile drummers around. From his early work with Elton John, then as a member of Paul McCartney's Wings, and currently on tour with Ian Hunter, the man could basically do anything. I remembered Pete's question about the beat and was glad that Steve seemed to pick out an appropriate pattern without too much trouble.

For upright bass Matthew chose Tim Luntzel, who we had seen playing all over New York. We brought in violinist Deni Bonet to fiddle in all the right places, and a choir made up of friends such as Terre Roche (of The Roches), Janice Pendarvis (singer with Sting and many others), Candy John Carr (from Donovan's "Open Road" band) and his wife Jane Cole, and Seeger superfan and sometimes live engineer Jeremy Rainer. Later in the day, the Outer Child Choir, led by Emilie Cardinaux, arrived and sang on the verse referencing "younger folks." Those kids were brilliant. The spirit and vibe of the session mirrored our day on the sloop — people singing and playing around Pete, a beneficent Pied Piper, drawing people together to sing and make a difference the way he had for 60 years.

We retreated to Matthew's studio in Brooklyn, where we added some final touches: Matt's pulsing harmonica, a multi-tracked choral vocal pad, and an acoustic guitar double. At that point, we were ready to mix. With the oil spill still an unresolved and continuing disaster, we wanted to rush the song out. In my mind, that is what Pete wanted and what the idea of a topical folk song is all about — a response, as well as an emotional release reflecting the news of the day, the way "Give Peace a Chance" and Pete's own "Bring 'Em Home" and other songs that appeared at the peak of a disastrous war. But, while Matthew and I were working on the track, Pete's record label, Appleseed, had been making other plans. Appleseed had brought Bruce Springsteen in to add a vocal on an album version of "God's Counting..." that Pete recorded with Lorre Wyatt. Then, due to a series of frustrating and nonsensical record label machinations, our single release was to be delayed so as not to conflict with other releases — for nearly two years.

During that time, however, Pete invited me to perform with him several times, and we communicated often by phone and letter. I treasure those letters he wrote — often assuring us not to worry, that our recording would be released in due time. One special concert took place at Symphony Space in Manhattan, a benefit for the Clearwater Foundation. The show featured Suzanne Vega, Tom Chapin, Arlo Guthrie, David Amram, Loudon Wainwright III, and others, honoring our mutual friend, George Wein. After the concert, we were greeted at the door by a huge group of protesters from the Occupy Wall Street Movement. As the concert ended, we all marched down the center aisle of the theatre, out the front door, and joined the group, led by Pete singing "We Shall Overcome," and many other songs, as he walked with two canes the 20 or so blocks down to Columbus Circle, while CNN and other media surrounded us. It was an inspiring evening that led Matthew and me to contribute a track "Hey, Can I Sleep on Your Futon?" for Occupy This Album, that was released soon after on Razor & Tie Records.

As November of 2012 neared, we were finally given clearance to release "God's Counting on Me, God's Counting on You." Talking with Pete, we chose Election Day, November 6, 2012, to release the single on iTunes and YouTube. It truly was a "release" for us, and a thrill to finally share the track with the world; although, by that time, the oil spill was no longer a topic in the news cycle. Regardless, the message resonated with Election Day, and hearing Pete's wise voice on a new recording was comforting to his fans. Nearly 100,000 have watched it on YouTube.

We stayed in touch and saw Pete perform a few more times, including at his beloved Clearwater Festival. Sadly, in the summer of 2013, Toshi passed away. Pete's health was also soon in decline and a little more than six months after her passing, he was gone. But what is really remarkable is that immortality does really exist. The lifetime of songs that Pete wrote and sang, and the very inspiration he gave to so many to sing out, really does live on in open hearts and minds. What makes the songs immortal is not just the message but the thoughtful crafting of his words and music. What makes the man immortal is that, let's face it, he was a saint.