Scott Hull is one of the top seasoned professionals of the trade — a skilled, sought-after engineer that has transitioned through musical, technological, and economic changes within our industry. Beginning as an intern at Masterdisk in 1983, his talent catapulted him through the ranks to become Bob Ludwig's assistant by '84, chief engineer by '94, and owner since 2008. Having started his career in the era of vinyl's dominance, he retains a rare level of expertise and insight into the art of bringing a vinyl record to market — a skill that's part art, part science, and very often misunderstood. As I was sitting down with Scott to have him master an LP project for me, I turned on a recorder and asked some questions that I hope will give some insight into the daunting task of releasing great-sounding vinyl as an independent artist or producer.

Vinyl's popularity is still increasing, but most independent artists don't know much about bringing a record to market. On a very basic level, can you overview the entire process, from mix approval, through mastering, plating, and pressing?

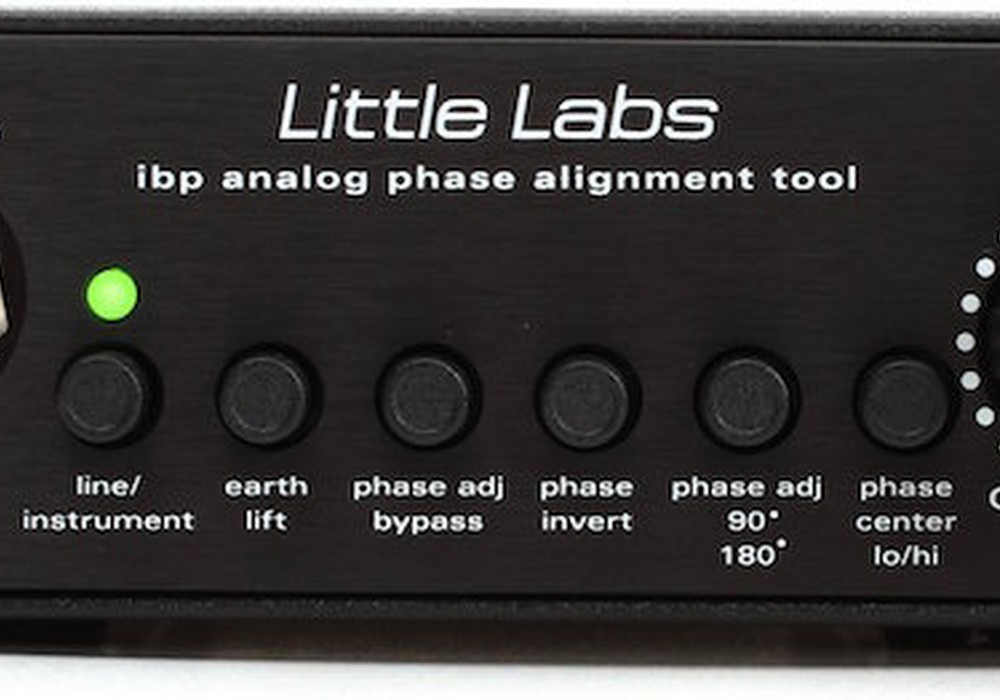

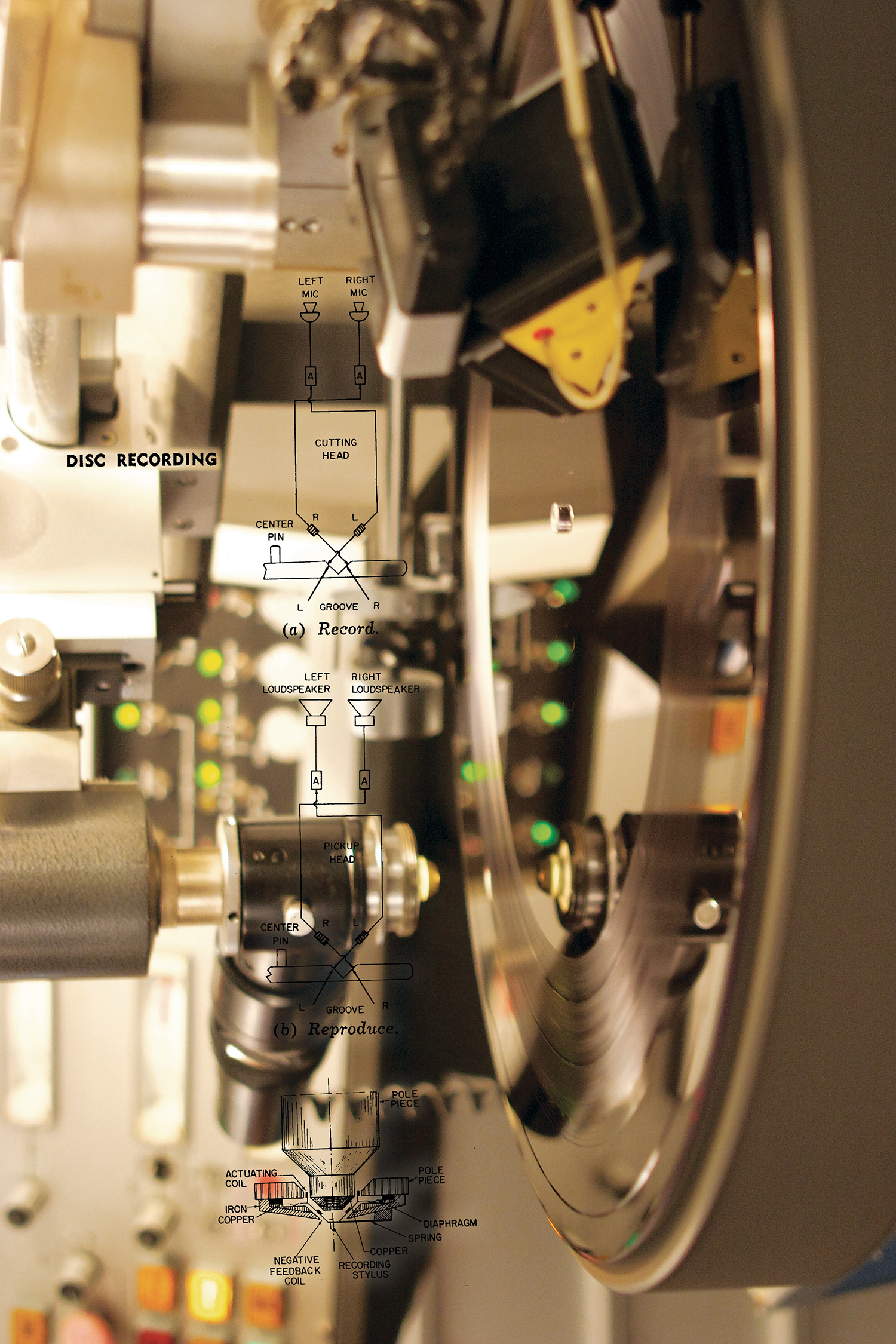

Well, to a lot of people, the process of making a record seems like a gigantic black box. But, in fact, there are many different steps — each with its own quality control issues. Making a custom master specifically for vinyl is similar to the process for a CD master, but it's done by an engineer that's a specialist in vinyl, and in a studio that's equipped for vinyl. Once you have an approved cutting master, the audio is fed to the lathe through the console, where any necessary compensations for volume, tone, and phase are made so that the record plays well and is technically of high quality. A reference disc is cut that looks just like a record; some people call these acetates, but in fact they're cut on lacquer discs. This will be listened to on a turntable in real time, and a trained ear will listen for distortion, excessive noise floor, and any issues with tracking or other disturbances in the playback. The mastering engineer, the producer, and the artist all listen and comment. Adjustments are made, if necessary, and then master lacquers are cut. Master lacquers cannot be played without damaging the disc, so we have to be really careful to document our settings from the reference in order to repeat them precisely after it's approved. The finished master lacquer is put in a box and carefully and quickly shipped to the plating facility where plating begins and metal parts are made. When the metal work is done, the pressing plant cues up to make test pressings, which are then sent back to the client for approval. After test pressings are approved, a production run is made, and the records assembled and shipped. Then boxes and boxes of records show up, and you have to figure out where to put them! [laughs] But each part of this process has important QC [quality control] steps, and if you have no touch points along the way, chances are high that not every one of your records is going to turn out great.

With a process that has so much room for error, how can an inexperienced producer or artist get top quality results?

Well, they really have to align themselves with people who are known for quality. It was a standard quote from the heyday of Masterdisk vinyl cutting — I'll attribute it to Bob Ludwig, but I'm sure it was passed down from someone to him — "perfect is close enough." When it comes to disc cutting, that's almost the only place to be. Spending enough money and time is one of the big requirements. If you're setting out to make an inexpensive record, that's okay, but you can't expect that to be an amazing piece of vinyl. The music's still going to be about as cool as it was ever going to be, but there's a higher likelihood of defects and those sort of things.

Between mastering, plating, and pressing, does it make sense to cut corners in one area, if you must, over another?

You don't have to go to the most expensive plant on the earth to get a record that plays when you put a needle on it. Even some of the least expensive places will make an average-sounding record, and will do it fairly quickly. Knowing your audience is really important. Are these audiophiles that are buying the record because they love the sound of vinyl? In that case, it'd be kind of silly to make them a cheap record — they'll turn off from your project, as opposed to being turned on by it. But if it's for the 7" crowd, and all about the attitude and the vibe, you might be wasting your production money on a really precision cut and [pressing]. Not to say that that wouldn't sound better, but whether or not your customers are going to care... To try and answer your question a little bit more directly — I think the cut is important, because if you don't start with a good groove, it doesn't matter how you plate it or press it, it's going to be noisy. If you know you'll be cutting corners by using a less expensive pressing facility, then you may really want to make sure it gets cut well and at a good hot level, because that will help you [beat the noise floor]. If you've got challenging material and you send it to [an inexpensive] mastering guy, he's going to lower the level, roll off the bass, and roll off the top end. Then it's going to be soft, and it's going to be pressed on pretty crummy vinyl. That's going to sound remarkably sub- average. [laughs]

Are there mixes that will absolutely sabotage you? Are there tracks that just can't be cut well?

Almost anything can be cut, but everything gets proportionally harder to cut as it gets louder. Even out of phase bass and terrible sibilant distortion can be cut. But if you take a record that has very harsh vocal sibilance and compare it to a record that doesn't — with the same music, the one with the harsh sibilance might have to be as much as 10 dB lower in level. That's massive! One of the hardest things to cut well is heavy digital peak limiting. The lathe just doesn't react well, and it often requires the level to be reduced to cut it cleanly. But for every dB you lower the level, the physics start to work on your side. There are still a few really extreme things that can't be cut, like a very quiet recording with a large low frequency excursion happening on one channel only. But that kind of thing is so rare in pop music, I don't like to tell people to limit their production too much. You know, if The Beatles could do stereo panned drums and vocals, why can't we? A really good mastering house might make some subtle compensations for that, but you might just barely notice... if they were pointed out to you. It really depends on your desire to have a loud record. Vinyl has a certain noise floor. If the level cut into the disc is low, then when the consumer turns the volume up, the noise floor will come up. Conversely, it's a better situation if they actually turn it down a little bit, because then they're turning down the noise floor.

Can you explain briefly the difference between lacquer and DMM [direct metal mastering]?

Most of the records that we own were cut with a lacquer master. Lacquer is a paint type of material; it's put onto a disc and we etch the grooves into it using a sapphire stylus. It's somewhat soft — it has to be soft enough that we can cut it — but it's not really "wet." It's semi-hard. Direct metal mastering is the same types of grooves cut into a copper disc. As you can imagine, solid copper is a whole lot harder and more resistant to being cut than lacquer. The forces involved, and the tools involved, are different. You can't cut lacquer and copper on the same lathe. It's inappropriate to make blanket statements — and there are a few times when copper might be beneficial — but most peoples' reaction today is still really similar to what it was in the late '80s and early '90s when DMM first started. It doesn't feel quite as warm. Not only does it tend to exaggerate the high-end a little bit, but sometimes the low-end has to be rolled off, or is just mechanically rolled off a little bit. One of the advantages of DMM cutting is that you can skip one of the plating steps; you can go right to a stamper because you can plate the copper part multiple times. If you're doing relatively short runs, you may really find that DMM is going to give you a decent product at a better price because some of the setup costs are [less] expensive. But when it's about the sound quality, and when it's about making a high fidelity record that people really want to absorb themselves into, it's almost always lacquer.

Another engineer we both know has cut on your lathe, and it's interesting to hear him talk about it — it's almost how I might talk about a particular favorite guitar or favorite cymbal. Do different lathes of the identical make and model each have their own personality?

Not only make and model, but actual iterations, as well as the way it's set up and aligned is incredibly crucial. Here in upstate New York we have the ability to tap into Chris Muth's [Tape Op #45] vast knowledge of setting up lathes. He can literally walk into a room, spend a couple of hours, and it will sound different. You know that a lathe across town that's set up differently won't sound the same. It's pretty dramatic; it's like taking a guitar that's almost unplayable, and having someone set it up so that it's feeling really great and in tune. It's that kind of dramatically different. I had a project not that long ago where I was like, "Let's just see how loud we can cut this." I cut it at a decent level, and it sounded pretty good. I tried it a little bit louder and it still sounded amazing -I was able to get quite a bit louder with it, even on my cheaper playback system. I couldn't believe what this lathe was capable of putting out! And this was an orchestral recording — loud brass and big drums with full dynamic range, no compression, full transient response... the music just leapt off the disc with that kind of level. On someone else's lathe, I'd partially be guessing because I wouldn't know how they had it set up, or what it would be capable of even if it was the same model. Walking into someone else's room, it takes you quite a while to figure out whether the problems are with your program or with the lathe. It's so tweaky, there are so many interrelated issues to deal with...

A lot of people on a budget elect to use in-house cutting at their pressing plant. What do you open yourself up to if you go that way?

I used to be a little less frank about this, but the results that have been coming in over the last few years... the record will almost certainly be underwhelming, in both level and tone, and it's pretty likely that the groove isn't going to be all that clean, either. I'm casting a big net, but with the domestic plants that are generally on the cheaper side, you've got to think about what's motivating the cutting engineer. If I was hired by a plant to cut in- house, they'd have to break me of every habit I have. I reject sometimes up to 10 or 12 percent of lacquer [blanks] in the box. If they're not of first quality, they get rejected. The guy who's in the plant is going to cut on every disc, because if he uses up more lacquers than he's supposed to, that's extra cost. That concept goes through the entire process — how long do you go before the cutting stylus needs to be changed? How much are you willing to push the level? I've seen and interviewed some of these cutters. Most of the time, they're not going to be creatively involved in your music. Monitoring the level is going to be low. They're going to look at a couple sets of meters, and if there's low frequency information, they're going to take it out. If there's too much high frequency information, they'll roll it off. There's no discussion about whether it's right, or just for the particular kind of music. Look, I'll give all those guys a free pass. Maybe they're just not given the opportunity to take that level of pride in their work. If I was in the plant, I wouldn't be able to do what it is that I do because it's inefficient — they'd need three of me to cut records fast enough! The motivation there is to get the job done fast and not have it be rejected by the plant or by the consumer. The problem is, that's incompatible with quality audio. It is going to be pretty underwhelming, with only an occasional exception.

A lot of these plants, these all-in-one shops, publish guidelines for things like maximum lengths of sides or whatever...

It's all to make it easier for them to cut. That limit, that 20 or 22 minute side limit... that's all about them being able to cut it easily and quickly.

Can you remember the longest 12" 33 RPM side you've cut with good results? I realize it's program dependent, but...

I had a rock thing that was almost 30 minutes. When you get over 25 minutes for rock, you always kind of worry about it being too long, but they had set up each side to have, not just a mellow song, but an acoustic song, and that saved so much space that I was able to cut the whole side at a pretty decent level. Compared to an average 20 minute record side that might have a VU level around zero, this was -5 or -6 which... you know, you work pretty hard to get each half a dB, but it sounded good. It wasn't a joke. You can cut over 30 minute sides, but it's just going to be very soft, and when you turn it up there's going to be a lot of record noise. That's the only real drawback. If you're kind of cool with it being noisy, it's going to be fine.

Can you explain what diameter loss is, and is there a way a side can be programmed where it wouldn't be much of an issue?

If you look through your record collection, the fourth or fifth song on the side tends to be a down-tempo song without heavily compressed drums in-your-face. That's because the inner part of the disc has progressively diminished high frequency capacity. Diameter loss means that the high frequency response of the disc drops off very gradually and very subtly as you go toward the label. We don't really worry about it too much for the first 60 to 70 percent of the record; as far as we're concerned it's pretty much flat. It's barely down a quarter-dB until this point where it starts to drop off a little quicker. There are conflicting issues, where the high frequency response actually rolls off, so it gets mellower on the inner part of the disc. But the likelihood of high frequency distortion goes up, because resolution [is] dropping. If you think about the circumference of the record, at about 12 inches versus one at about 5 and a half inches, near the label, that's less material going past the stylus every second, and it creates a slightly lower resolution. We can compensate a little bit with EQ, and it used to be a standard thing — 78s had "diameter EQ." As the carriage went across the record, it would turn a potentiometer that would increase the high frequency response as it went in. The problem with LPs is that we also run into some additional distortion, so you can't just add high end. But, if the record's cut at a reasonably low level where you're not really in danger of high frequency distortion, then you can add a little high frequency EQ to those inner bands to mitigate the problem. But you have to know what you're doing; you have to have experimented with it enough, had some successes and some failures, and figure out what works.

Is there a preferred time window in which the lacquer should be plated? As the lacquer hardens, does the sound degrade?

There's only one area that's dramatically affected by time, and that's an effect called pre-echo or groove echo. A record is cut by a hot stylus that's basically carving out a groove, but it's also partially deforming the [lacquer]. And it's like a credit card — you bend it and it snaps back. The soft plastic [lacquer] has the same thing, but to a much smaller degree. Now if two grooves are close together and there's a loud one that follows a soft one, after the loud one is cut, when it springs back, it actually draws the material over from the adjacent groove. It doesn't overcut — you could look at the scope and not see it. But if you play back this other groove, you'll hear a ghost of the groove that's to come. We tend to add space, or "land," before spots that could be echo-prone. If you do that really well, the likelihood of being able to hear the pre-echo is less. But, as with anything else, it's program dependent. If it's hard rock that starts loud and ends loud, and doesn't have a lot of dynamics, I'm personally aware of records that were plated weeks after they were cut and sound fine... absolutely not an issue for about 70% of the music that we're dealing with. It becomes a little bit of an issue with singer-songwriter projects where there're quiet moments followed by a loud, solo vocal. High frequencies don't really pre-echo and bass frequencies tend not to pre-echo, or at least you don't notice it as much. It's right in that midrange where you notice. A vocal, like after the band stops and there's half a bar of silence and the vocalist comes back in... that could be a pre-echo problem. But that pre-echo is one of those mysterious things about vinyl. It's in there messing up the grooves all the time; you just can't isolate it and hear it. But it's probably affecting the way we hear the record, on a subtle level, as much as anything that has to do with vinyl. It's part of the special sauce. [laughs]

A lot of facilities offer both two-step and three-step plating. Can you briefly explain the difference, and is there an advantage to one over the other sonically?

A two-step process has fewer plating steps. Plating done well is, again, a function of cost. How many runs do they make before they change the chemical? They have to use a particular grade of silver, or nickel. Are they using the higher grade, or getting by with a lower grade? In a practical sense, the quality of the materials is more important than the number of plating steps. The only real difference is what your proposed quantity is going to be. A mother can be plated four, five, six times, depending on the plant, and depending on how high they've set their standards. Each mother could make four stampers, each father could probably make four, five, or six mothers. So you can get a lot of records out of a three step process.

Quality of new pressings — both reissues and new releases — has been mixed lately. What would you attribute that to?

Here's the big thing: in the '70s and '80s they were making much, much larger runs of each title, so a pressing plant might run for three or four days on one title. They're lucky if they even run for half an hour on one title right now. You can imagine all the changeover! Those first 100 and those last 100 copies tend to be the worst, but now those are the only 200 that are going into circulation! If you were pressing 10,000 you'd probably just reclaim the first 100, because they weren't going to be [first quality]. There are plants that manage to keep quality up, and those are almost always the more expensive ones, because they're going to cycle their presses longer, they're going to throw away discs with minor defects, and they're going to discard that stamper before it really fails. They're going to reject metal parts that don't look right, and do them again, without the client even knowing about it. Those are the plants that insist on quality, and it's all invisible to the producer — that's all hiding between that point where you approve your ref and when you get your test pressings.

So how many pressing plants in the United States right now would you say are doing truly excellent work?

The irony is that most of them are capable of doing good, high quality work — it's just the consistency. Even of the ones that are not in my regular recommended list, I have heard good pressings from each one of them in the past few years. It's just that I've [also] had experiences with them not sounding great. At least a couple of plants have had problems with the metal departments. One plant reportedly fired their entire galvanics department. They outsourced it for a while while they trained a whole new set of people to run the metal work. That would explain a whole lot of what I heard, because it was really inconsistent!

If someone was researching which pressing plant to choose, what should they look for? Should they just ask their mastering engineer?

The mastering engineer should second your opinion, at least. The best is to find out where someone else's record was pressed that really sounds good, because at least you know they're capable of that.

Speaking of the inconsistency of the less desirable places, what causes that inconsistency?

You never really know for sure, but there are at least a few different factors to consider. Press cycle time — how long they leave the press engaged in the material — affects what's called no-fill. If they're running the press at a little too fast a cycle time — which might just be a quarter-second in duration — they may get several hundred more pressings done a day. But if the material doesn't really get to fill out every little spot, that can make a ripping or tearing sound in the groove. If they choose a type of vinyl that doesn't flow quite as well, that — coupled with a faster press time — could cause no-fill. If it's a really short run, the actual heat of the press might not have gotten all the way up to temperature. There can also be issues in the plating. Because it's such a manual process, the quality is related to the experience of the operator. For example, there's a de-horning process where they will actually physically carve the horns off the top of the groove. It's an area your stylus doesn't touch, and it supposedly makes for a better mold release, and therefore a quieter record. But the process itself creates crud, and if it's not cleaned out of the groove properly you'll have problems. When the record companies' output was records, it was more like what you'd expect if you were doing a custom print run, where you'd go sit on press, they pull a few sheets off, and you compare it to your sample. You might say, "No, this red's not quite right." You'd turn a few dials and then run a few more and say, "Yeah, okay. That's more like it." That's the way records were made. Right now, if you were to reject a test pressing, it could really set your project back three to six months. Back in the day, when we were sending records out every single day to the same plants, we were getting test pressings back within days of cutting them. The feedback cycle was much shorter, and you could actually tell when someone's plating bath needed to be changed, or if they had changed formulations on the silvering or the tin where, suddenly, there's a new timbre. Now we're cutting a few records and waiting, and getting them back two to three months later. Its not nearly the feedback cycle where I could say, "Okay, I cut this yesterday on a brand new stylus and it looked amazing, and now I've got all these noises in the groove."

So was there a golden era of record making? When would that have been?

In my opinion it was right around the mid-'80s, when the volume was really high. But there was a distinction, even then, between the places doing exceptionally high quality — Europadisk, Deutsche Grammophon...

Would it be possible to get that level of quality now?

Occupational safety standards have made it impossible to get exactly that quality. Plating, chrome, tin, and silvering; all these things are more highly regulated, so maybe we've lost a few percent from not having as good of materials. But economics is probably the biggest factor. If we were pressing 30, 40, 50,000 records instead of 1,000 records for each title, I think we could insist on a lot higher quality, and the plants would be making enough money to put some back into their equipment and materials. But you know, it's pretty darn good for where we are at.

A lot of people want to do colored vinyl, picture discs, glitter, transparent — how do these impact the sound, relative to black vinyl?

Traditionally, they all suck compared to black vinyl. But my experience lately is, if it's done well, they can sound pretty darn close. I cut two picture disc projects and a clear LP that, if you did a blind listening test, you'd never know they weren't black vinyl. Back in the day they didn't have clear vinyl figured out. Now they do, and it's quiet. Head-to-head, against 180 gram high-quality vinyl? It's hard to tell, when it's done right, but that's also inconsistent. One plant did two different picture discs for me for the same artist; one was quite a bit quieter than the other, and I never found out what the reason for that was. The one that wasn't as quiet was acceptable and quite good, but the other one was remarkable.

But, as a rule, the noise floor of those types of specialty vinyl is higher?

As a rule, the colored vinyl tends to be a little noisy. But some of that is old thinking. My advice is to make sure the tests are made on the vinyl that you're going to be running them on. Every plant that I work with will send you samples, so if you want to do a white disc, have them send you samples of a white disc that they've pressed. The big piece of advice is don't just assume that the way it worked the last time is the way it's going to work the next time.

Is there any advantage to heavier weight vinyl, other than warp resistance?

Most of the pressing plants will say, "No," except that the product feels more expensive, and the consumer tends to be more impressed by it. It's the 140 gram compromise. I believe the plants are correct — that's heavy enough to not have any warp issues. Being critical about what vinyl you let into the press probably has more impact on the sound quality.

Like how much re-ground [recycled vinyl] versus virgin vinyl?

Yeah. And there are two thoughts on that. The reclaims, since they've been processed once, have a slightly different chemistry than virgin. And not everybody says virgin vinyl is quieter! You pick up a little more potential non-vinyl bits in the re-grind, but it improves your chemistry. So you've got to listen to everything, and try to make notes on your experiences on what you hear.

What's the right way to evaluate test pressings? Because I feel like a lot of people don't really know...

Yeah, they don't. Test pressings are made on a manual press. They will, by and large, have more noises on them than your final [product]. My experience is that the outer few revolutions of a test tend to be quite a bit noisier than the rest of the disc, so I take that into account, knowing that once the press temperature stabilizes, that some of those noises in the first few revolutions don't stick around. There's a reason they send you more than one test pressing: One tic on any one copy might just be a little bit of vinyl left on the stamper from a previous press, and the separation may not have been perfect. But if that pop sounds exactly the same, and it's in exactly the same spot on more than one test pressing, that's potentially a defect on the stamper. That could go all the way back to the mother, or even the lacquer. You can't know that unless someone plays the mother to find out.

And you can actually play the mother?

The mother is a metal grooved record that can be played. I've tried having the plants play them and report, but their level of quality concern and mine aren't always the same. That doesn't mean it's always less — some places they may be even more critical than I am! Listening to a test pressing, there are going to be noises. You're going to hear enough noises that it might even startle you — but if they're somewhat random low-level noises, it's okay. Anything that skips, don't immediately panic. Your turntable may not be set up correctly. So we'll usually tell people to listen to it on multiple turntables, but in fact, they may not have any of their turntables set up properly! A great idea is to have a friend at a local hi-fi shop that has a nicely set up turntable [play it for you]. And your cutting engineer should also listen to your test pressing for you, or with you. They may charge you for the time, because it takes time to do it right, but who better? They know what it's supposed to sound like. We also know what kind of compromises we have to be aware of, and when to say, "Yeah, those noises are there, but it's going to be really difficult to make them go away. We could re-cut it, and re-plate it, and end up with different noises!" [laughs]

You mentioned turntable setup. Will a great sounding record sound better on a poorly set up turntable, versus how a poor record would sound on that same poorly set up turntable?

We have to cut this record with the idea of who's going to be playing it back. If this is for a limited-edition label that caters to owners of $10,000 turntables, we can cut with a really high level of precision, and even cut things that might be a little risky. We know that [market's] equipment, properly set up, is going to track it just fine. But if the audience also involves people that have their first USB turntable, and they've got a textbook under one side to keep it kind of level, they're not going to have success playing that same record — even though it was cut perfectly. We don't like to set up for the lowest common denominator, but sometimes it's risky to set up for the highest, as well. That classical record I mentioned earlier was one where we decided that it was an aficionado's record — we opted for going all the way with that one, and there's a chance that it could skip on a lower quality turntable. That's risky! [laughs] You know, I'm taking my client's reputation into my own hands at that point. But it's done with forethought, and done with consulting. That was a deliberate decision to give the upper 10% something really special to play.

_display_horizontal.jpg)