Not only is Susan Rogers a record producer, engineer, mixer, and audio electronics technician, she has a doctorate in psychology (having studied music cognition and psychoacoustics) from McGill University. As an engineer Susan really got her start working with Prince from 1983 to 1988, including albums like Purple Rain, Around the World in a Day, Parade, Sign o' the Times, and The Black Album. Her other studio sessions have included artists like Barenaked Ladies, David Byrne, Toad the Wet Sprocket, Rusted Root, Tricky, Geggy Tah, and Michael Penn. She is currently the director of the Berklee Music Perception and Cognition Laboratory, and is an associate professor at Berklee. Portions of this interview were conducted after a listen to a vinyl LP of Purple Rain during the "Saturday Night Listening Party" at the Welcome to 1979 Recording Summit (held every November in Nashville), and the rest of the interview took place between me and her the following day.

How did you end up as a tech?

I worked for a company called Audio Industries Corporation in L.A. for Hal Michael; HM was what he was known as. When I was a kid, I always wanted to make records. I took piano lessons and I had zero affinity for it, but I played the radio and listened to records like a fiend. Sometimes on vinyl albums there would be a picture of the studio, and I fantasized about being in that place where records were made. I didn't see myself in terms of what I would do there, because I didn't know, but it wasn't performing. Then when I learned that there are people who make records...

How did you learn that?

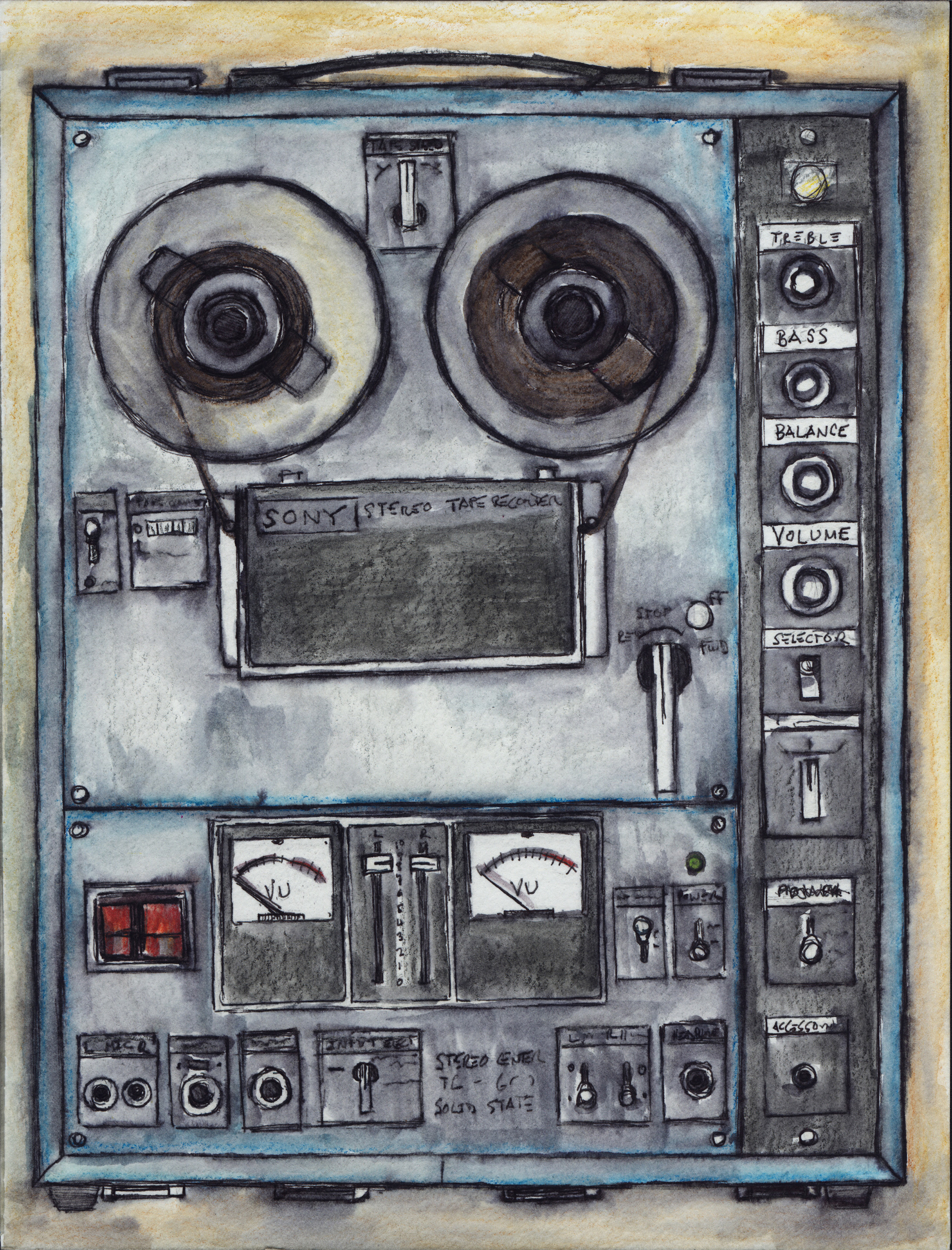

There was this school called the University of Sound Arts, right in Crossroads of the World [in Hollywood]. They had teachers from Wally Heider Sound, Sunset Sound, and Capitol [Studios]. They'd hire some of the greatest engineers in the world to moonlight as their teachers. My friend said, "I'm going to go to this school and become an engineer." There was no way I had money for that, but my friend was able to get me a job as the night receptionist at that school. I couldn't afford the classes, but I could afford the books. One day I overheard a tech talking to a student; he worked for Wally Heider Studios. He was telling them, "You want job security? Don't become a recording engineer, become a maintenance tech. You'll always have a job." I thought, "Well, then that's my career." I bought books and started learning about electronics. I read Modern Recording Techniques, 1st ed., and the Don and Carolyn Davis books on acoustics. Shortly after this process began I saw a "Help Wanted" ad in the Los Angeles Times. It said, "Audio Trainee Wanted." It was for Audio Industries. I applied; I knew nothing, but they liked my enthusiasm. They trained me to be an MCI service technician. At night I was studying my ass off with those MCI manuals and all those electronics books, and then, during the day, they were teaching me to solder, how to wire studios, and how to do simple repairs. One studio I was visiting frequently was Rudy Records, owned by Graham Nash and David Crosby, in Hollywood. They had an MCI console and tape machine that would frequently fail, so I would go on service calls. They asked me if I would leave Audio Industries and be their studio maintenance tech in 1981, and I took the gig. I finally got to fill in on occasion as an assistant engineer, and for the first time I was actually watching sessions happen.

Who was the lead engineer there?

There was an assistant engineer named Jay Parti, who also did some firsting [first engineer]. Crosby, Stills & Nash were working on the Daylight Again album. Stanley Johnston and Steve Gursky were two engineers working on that album. Mostly it was a one-room studio for hire. The Eagles, Bonnie Raitt, David Lindley, Joe Vitale, Mike Finnigan, and people who were part of that CSN, Eagles, and Kris Kristofferson crew would come in.

A lot of great musicians!

The late Don Gooch was an engineer who had been associated with CSN for a long time. Don would kindly allow me to come at night and observe his sessions. One of the first sessions I ever witnessed was the Burrito Brothers, with Don engineering.

Were you picking up session flow, and things like that?

I was starting to see how it worked, learning to listen to music as it comes together, and learning to develop that decision criterion for what constitutes a "perfect take." I'd hear the musicians play it over, and over, and over again. It was clear that the producer was searching for something that he hadn't heard yet. I'd listen and try to match my ear against theirs to see, "Will I know? This sounds right to me. What's the producer going to say?" I was learning the practical aspects of record making, plus I was learning our business. "Who are these people? What do we value? What do we...