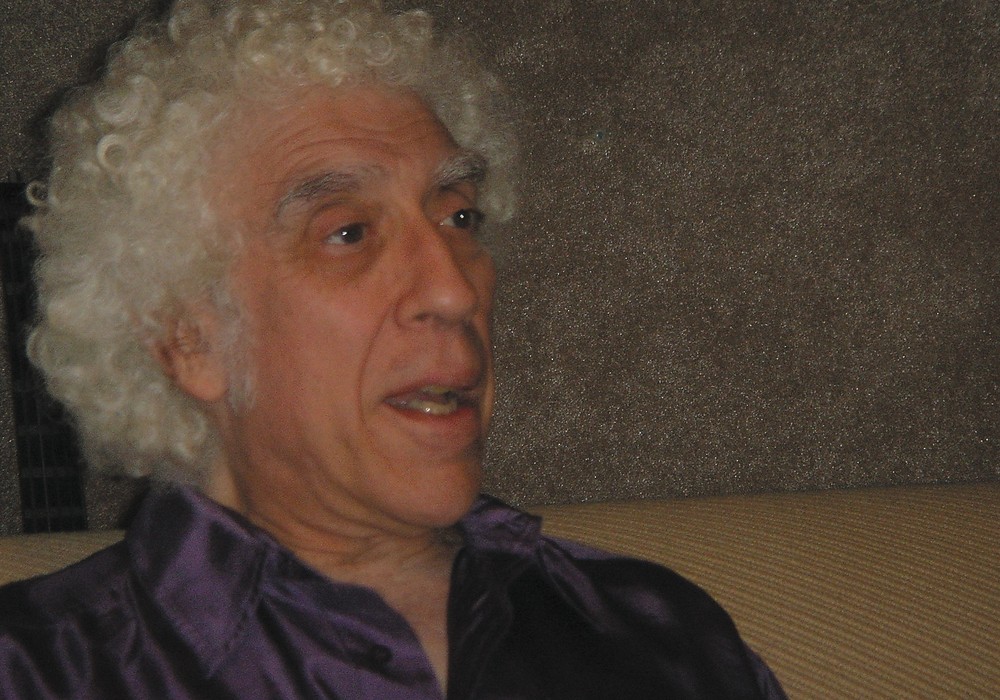

As far as I can reckon, albums that Michael Wagener has produced, engineered, or mixed – including Mötley Crüe's Too Fast for Love, Skid Row's Skid Row, Metallica's Master of Puppets, Poison's Look What the Cat Dragged In, Extreme's Pornograffitti, and Dokken's Under Lock and Key – just to name a few – have sold approximately 50 million copies combined. I personally purchased dozens of these records in the years between 1983 and 1992, and spent countless lonely "nerd-with-a mullet" (and a Kramer Pacer guitar) hours dissecting the guitar tones and licks contained therein. Other producers from the era, like Andy Johns [Tape Op #39], Beau Hill, and Tom Werman [#102], were all making great, heavy records as well, but to my young ears albums with a Wagener credit were guaranteed to kick ass even more. It was something about the solid kick drum, the explosive bombast of the snare, as well as the sheen and girth of the guitars that sounded more substantial and authoritative. Needless to say, I was very nervous while driving through the Nashville suburbs in search of Wagener's WireWorld, a compact but seriously kitted-out studio, where the producer continues to develop new talent and collaborate with old friends, like Great White, whose new album Full Circle] had wrapped a few days before my visit. Michael Wagener is a cheerful, genial, and humble man who still loves dialing in wicked guitar tones, geeking out on gear, and, of course, making killer records.

Why did you decide to build WireWorld?

I had a studio on Wolf Hoffman's farm, the guitarist of Accept, which was close to Gallatin, Tennessee. He moved back to Germany and other people bought the farm. Then, all of a sudden, it was going to be auctioned off in three weeks, but I had six months of work booked and paid for. Luckily they let me stay and finish everything, but I realized that this should never happen again, so my wife, Tina, and I decided that we needed to have our own place. In 2008 we drove around and found this place. The listing said, "Possible studio in the back," which at the time meant a little guesthouse, where maybe you could do an acoustic guitar and vocals. About nine months later we started building the studio you see now. It took us about a year to do the build, and, as you can imagine, that's a year of no money coming in and enormous sums of money going out.

Has the investment paid off?

With the way the budgets are nowadays, and the way the whole thing is structured, if you say the words "producer's advance" bands just look at you with glassy eyes and don't understand what you're talking about. But "studio rate" they understand. It's just a number that you pay for recording. I work a lot with new bands, where there's almost no money, so if I had to rent a studio for $2,000 a day I would never be able to make it work. But I can accommodate musicians with my own studio. If we go a week over, we go a week over. Nobody cares, and we make a better product.

Let's go back to the beginning. You started your musical journey as a guitarist, right?

Yes, I got my first guitar when I was 12. Udo Dirkschneider – whom we all know now as the lead singer of Accept – he and I went to school together, starting around when we were seven years old. We practically spent every day together. We decided to have a band together, but we couldn't come up with a name so we called it Band X. That went on for a while, to the point where it was a real band where we were really playing and coming up with songs. Then, at the point where it started to get serious, I got drafted to Hamburg, which was 350 miles away from Wuppertal where we lived – so that was the end of band practice for me. I left the band, and my last action with Udo was coming up with the name Accept. I pursued guitar in the army for a little while, but it just didn't come together.

Did you make the transition to engineering and producing right after coming out of the army?

No, I started working for a company called Stramp Amplifiers. The boss' name was Peter Strüven… Strüven Amplifiers… Stramp. We built tube amps for Rory Gallagher, Leslie West, Jack Bruce, and John Entwistle. When I started at Stramp, I didn't know much about electronics, but I went to school and got my degree at night. Stramp was basically a family; it was the boss and his wife, and then there were two more technicians and two more assistants like me. We would sit there late at night and come up with the new gear that we should build, like, "Have you seen the new Trident board? We should check that out." Or the boss would go to America and find out about some parametric EQ and decide we had to do that. It was wonderful and I got to do everything, from packing boxes, to sweeping the floors, to designing electronic equipment. We also ended up importing Otari machines – the big old 8-tracks – and building our own studio consoles. We had a little 8-track studio for demonstration, and I found out that working with the gear was a lot nicer than having to build it! Peter's wife died at 29 years old, and that kind of broke up the whole family. He...