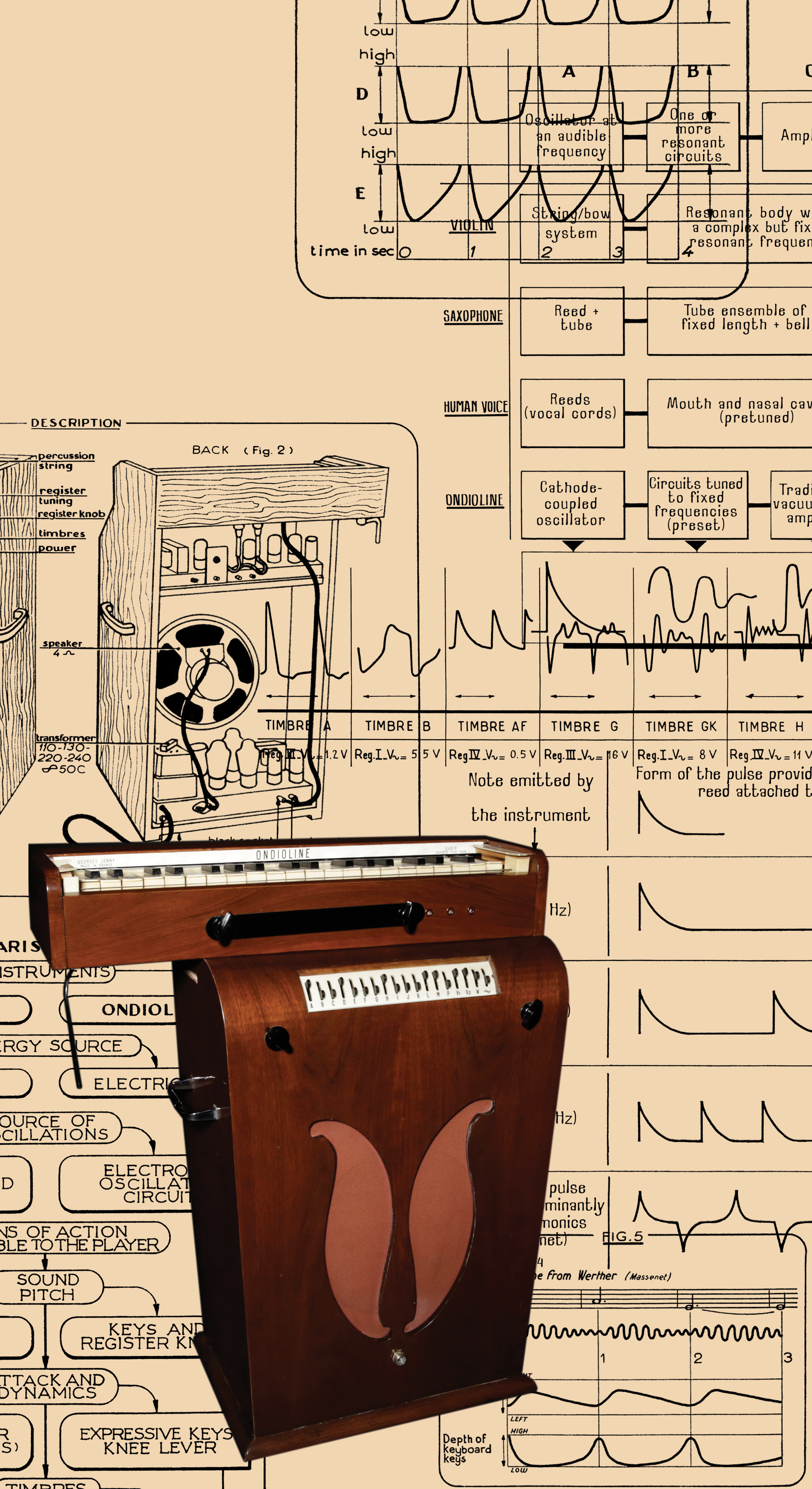

Technician, musician, and recordist Stephen Masucci has been a friend of Tape Op for many years, helping set up interviews and turning us on to some great people. His band, The Lost Patrol, has been a favorite listen around the office as well. But his real skill is rebuilding synthesizers, consoles, and all kinds of gear. And working for Gotye/Wally De Backer [see his interview this issue], Stephen has restored over six Ondioline keyboards; a rare French proto-synthesizer.

How did you end up in the music instrument, console, and keyboard restoration world?

I was always a big fan of people like Wendy Carlos, Isao Tomita, and such. As we headed into the '80s a lot of that synthesizer gear was being thrown away. People were buying [Yamaha] DX7s, and you could get a Minimoog for $200 in pretty much mint condition. I had some instruments I'd come across, but I couldn't afford to get anybody to fix it. I did meet Walter Sear [Tape Op #41] very early on, who became a mentor in electronics for me. A college I was doing some work for had a Moog synthesizer, and they were like, "Would you like to try to fix this?" I said, "A Moog synthesizer!" Other people had this type of gear, and then they started getting my phone number. I like doing restoration where people say it can't be done. Of course it can be done; we went to the moon! It's just time and doing the research.

You restored some Helios consoles as well.

I did a couple of Helios. I've done lots of custom work and builds.

How did you and Wally meet at the beginning of this whole Ondioline restoration?

He'd been enamored with Jean-Jacques Perrey's music for years, and he found this instrument was at the core of it. He quickly discovered how rare they were and that none of them really worked. He finally found one in Connecticut, of all places, that had actually been in a flooded basement. You can actually see the waterline on it. He got my number through Brian Kehew [Tape Op #93] or [musician] Rob Schwimmer. He brought it over, and I felt, "Well, I can"t make it worse. Let's have a go." It was already so bad. I kind of did a half-truth and said, "Yeah, I have fixed worse than this." And I have fixed some pretty bad things. I had to learn about the materials. The only reason I'm able to do this is because I have an amazing machinist friend who has a CNC [computer numerical control] machine shop. Another friend of mine is an expert in 1920s and 1930s tube technology. Then one other friend is an expert in 18th and 19th century fine wood restoration for museums. I didn't do this all on my own.

Wally hinted that you were at a point too where you were a little bored with some of the same restoration work you've had over the years.

Not bored, but it was starting to become same-y. I love doing it, and I love putting something back in the hands of a musician. The payoff is not that I restored the unit, but rather can the musician make music with it? Does the console let them forget about the console and make music? It's great to preserve the artifact and make it a functional, playable, tunable musical instrument that's reliable. But the real payoff for me is when a musician or producer gets to do their work and they're excited about it.

The Ondioline is very expressive and has its own unique voice. Bringing those back to life is a way to bring back music that would never be heard otherwise.

Absolutely. If Wally didn't do this, this would be lost. A lot of the music that he's doing with this Ondioline orchestra has never been played live. It was all studio recordings for a film or TV show. It's a really unique situation for me. We were very careful to make sure the restorations were complete and remained as authentic as possible. There's essentially no modern work-arounds on any part of them. I didn't cheat anywhere. There's no component that wasn't a part of the original machine. There's nothing in there that isn't really what would have been shipped from the factory.

What kind of methodology do you take with a job like that?

The whole device comes apart completely. I take lots of photographs and notes. If you look at the circuitry, the inventor, Georges Jenny, was certainly thinking outside of the box on this thing. It makes sense as...