The least surprising thing about the 2017 release of the Giles Martin remixed version of Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band is that its sonics – indeed, its very existence – was heavily and passionately debated. Audio engineers who work on historic recordings know they have to be tuned into that sweet spot, where presumed aesthetics need to shine through and residual noise is tempered enough to slip into the background, or slide away entirely. Even then, there are always fans who will prefer the original, fans who will clamor for the new release, and fans who won't hear the difference. The reissue market is massive, and so is the number of recordings in need of preservation, restoration, and remastering. Aging rock stars are repackaging their catalogs. Labels like Numero Group, Light In the Attic Records, Anthology Recordings, Captured Tracks, Awesome Tapes From Africa, Omnivore Recordings, and many more are digging up lost or forgotten recordings, demos, B-sides, and long neglected catalogs. Mastering reissues is a specialty with its own set of considerations, technological tools, and audience expectations. In the broader world of record making, we all have the same goal: to make it sound great. But how do we do that when our sources are damaged tapes, well-worn LPs, or even cassettes that have been buried underground for years? I asked three other mastering engineers who have restored and remastered many reissues, in addition to mastering plenty of new recordings:

Jessica Thompson: Philosophically speaking, what should a reissue sound like? My take is the Hippocratic

Oath version of remastering: first,

do no harm.

Michael Graves: It should sound great. That's really the one constant I can think of.

Josh Bonati: Equal to, or better than, the sound of the original release.

Maria Rice: Why don't we just digitize a copy of the original masters, send it to Disc Makers, and call it a day? Is it because some limitation of the original recording medium impedes the intended expression of the material (like noise, grossly imbalanced frequencies, excessive distortion; or intermittent artifacts of age, such as dropout, clicks, and pops)? Are we pulling many different sources together for a compilation, or creating a replica of one particular album? Is the intent to modernize a recording to fit in with current mastering aesthetics?

JT: Recently, I was working from a cassette of this total knockout record from South Africa in the mid-1980s. I was so entranced by the music, it took putting on my mastering engineer hat to realize how crappy that cassette sounded. The cassette had been created from an LP source, so there was this accumulation of LP noise, cassette noise, and age noise. I called the producer, and he reached out to his network to source a pristine copy of the original LP. I was blown away by the difference in quality between those two sources. We had to bump the release date, but it was worth it to take the extra time to find the best-sounding source.

JT: Describe a remastering scenario where the source material is damaged or sounds compromised and you were able to repair the audio for new audiences.

JB: A label discovered some special unreleased material on a lacquer disc – not a test pressing, not an acetate (dubplate), but a lacquer. This is the kind of disc I cut vinyl masters on for manufacturing. This disc had been cut 15 years ago on a lathe and never sent off. It had been stored inside a thin plastic file folder and was filthy. I have a VPI record cleaner for LPs, but lacquer discs are far more delicate than pressed records, plus the lacquer was 14-inches in diameter and wouldn't fit in my cleaner anyway. I have a good relationship with Desmond Naraine, from Mastercraft Metal Finishing in Elizabeth, NJ, who does the electroplating work for most of the records I cut. I took the lacquer there and had it washed in their pre-plating bath. This is a mechanically tilting tank that gently washes any dirt or dust off of lacquers before they enter the plating process. The resulting clean lacquer played and transferred like a dream – almost "digital" in its lack of surface noise.

MR: I can think of a particular instance when a track was transferred from an aged 1/4-inch tape that had suffered from significant shedding prior to arriving at our studio. As we had done all we could in the analog domain – baking and rewinding the tape, finessing the tape deck – we reached out to the label to see if they had an alternate source for the track. Unfortunately, ours was the only copy. So we had to operate. We used CEDAR Retouch to fix the microscopic dropouts – these were tiny little dropouts that aren't usually audible to the listener; but when you have many of them in succession, repairing them greatly improves the perceived quality of the sound. Then we needed to address some more audible dropouts where whole syllables, or even an entire beat, were missing. While I typically avoid making invasive edits whenever possible, in this case I performed some creative surgery in our SADiE DAW, cloning tiny pieces of drum hits and vocals. Editing a transfer from tape presents a special challenge, as two seemingly identical sounds will never have the same waveform due to tiny variations in speed, tone, and noise level. Also, working with so much audible damage has the potential to become overly complicated and heavy-handed, which puts us in danger of going too far. Therefore, if an edit didn't sound completely undetectable, I left it alone, allowing listeners to hear the recording as-is. A bit of aging is preferable to digital artifacts and awkward edits.

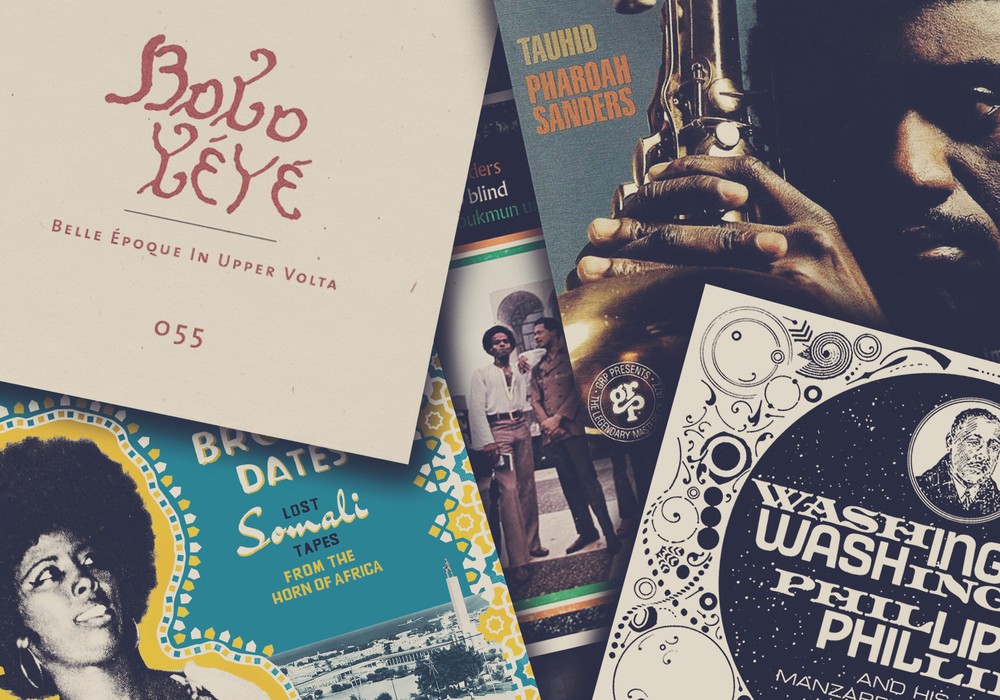

Josh Bonati, from Bonati Mastering in NYC, recently remastered the Pharoah Sanders albums Tauhid (1967), Jewels of Thought (1969), and Deaf Dumb Blind (Summun Bukmun Umyun) (1970) for Anthology Recordings. He also mastered and cut Coil's Time Machines, and the Milk 'N' Cookies box set for Captured Tracks. He regularly masters new records, and cuts vinyl for Sacred Bones Records, Dais Records, and many others.

With nine nominations and two Grammy awards, Michael Graves, from Osiris Studio in Atlanta, has proven he can coax the magic out of even the most compromised audio recordings. He has worked on everything from Cambodian 78s, to Hank Williams transcription discs, to Big Star remasters for labels such as Dust-to-Digital and Omnivore Recordings. He was a double Grammy nominee in the Best Historical category last year for Washington Phillips and His Manzarene Dreams and Sweet as Broken Dates: Lost Somali Tapes From the Horn of Africa.

Maria Rice, from Peerless Mastering in Boston, has been working alongside mastering engineer Jeff Lipton [Tape Op #34] and the Numero Group for over a decade, earning her two Grammy nominations for Numero releases such as Bobo Yéyé's Belle Époque in Upper Volta and Ork Records: New York, New York.

MG: I recently finished a compilation of Somali music from the '70s and '80s. What's interesting about the music scene in Somalia is that it was a socialist country and you weren't really supposed to own any recordings personally. So, no records. There weren't even any recording studios. You either consumed your music at any of the numerous live venues or over the radio. And most of the music on the radio was from live recordings. However, not everyone plays by the rules. Sometimes you want to have your own tape, right? There were these places where you could go in with a list of songs, and the owner would compile a cassette for you… mostly from music being played over the radio. In the late '80s, as the civil war started to ramp up, Radio Hargeisa – with one on the largest collections of recordings in the country – knew they would be a target, so they dispersed their entire archive to surrounding countries and buried large portions of the collection on the grounds of the radio station. The station was destroyed during the war, but afterwards some of the recordings were brought back and the buried tapes were unearthed. These are the tapes I was working with. Many of the cassettes needed physical repair before they could be played. Once that was done and they were digitized, I listened to them to try to figure out what I could do. There were lots of issues: pan shifting, pitch variation, changes in volume, drop outs, missing sections of audio (where it sounds like someone hit the record button by accident), tons of tape hiss, distortion, hums, and static. It was daunting. I started addressing the issues that I was familiar with first. Gotta start somewhere, right? I eventually got most everything under control as much as possible, but the hiss level was crazy. I started to pay more attention to the stereo sides and noticed that there really wasn't much discrete information there, mostly just hiss and echoes of the mid. When I listened to the mid alone [using mid/side processing], almost all of the hiss went away. This got me thinking about the source cassettes. Most of them sounded like third or fourth generation dubs. There were probably some tape head azimuth errors happening along the way on those dubs, and it was having a multiplying effect. I decided to make the really problematic tracks mono. This significantly reduced the hiss, and also helped smooth out the recordings in general. Then I did something I thought I'd never do – I added some fake stereo to the tracks… just a little bit. I usually hate this kind of thing, but it worked here. It brought back the openness of the original tapes, and it made the tracks that I mono-ed fit nicely with the other stereo tracks on the compilation. That's the thing about working with material that's incredibly compromised like this; it forces you to be creative and try things you normally wouldn't think of.

JT: There's a responsibility to the fan base of well-known records that are in the process of being remastered. In some ways, you know you're going to get criticized no matter what you do. Do you approach remastering differently with records that are well-known, versus deep cuts?

MG: I don't think I approach a remaster differently than a regular master. I always try to be respectful of the artists and musicians on the recordings that I work with, whether it's from a session in 1910 in Mumbai or something recorded in L.A. ten years ago. The level of public scrutiny will be different with the well-known recording, and that's usually in the back of my mind, but I've learned that I have to make the music pleasing to my ears first. I've tried to chase what other people are looking for, or what I think listeners might expect, and it never ends well; the process takes longer than it should, and I usually end up reverting back to the sound I had in my mind in the first place. I'm not saying that I won't take notes, or make adjustments that are requested, but I find that I get less of those if I start off doing what I feel is appropriate versus what I think someone wants. I just finished a Buck Owens project for Omnivore Recordings. I've done a few of these over the last couple of years. The first time I heard some of these tapes, I couldn't believe how amazing they were; the musicianship and quality of the recording was unbelievable. The Buck Owens sound is pretty legendary too; there's a whole genre of country music based on this sound, so any changes by me could be tricky. After those first tapes were transferred, I went about the mastering process as I would any project, making adjustments where I thought they were needed. Some of those adjustments were different than what had previously been issued. When I sent the masters in for review, I was a little nervous; but the label and estate ended up being very pleased. It can be intimidating, to the point of mastering-paralysis, if you think too hard about some of this. You've got to balance being respectful with doing what you think needs to be done.

JB: Sometimes a record is so well-known and well-loved that you can't really touch a hair on its head without pissing off the audience, especially if people were largely happy with the original sound.

JT: What is your responsibility to the original vision of the artist and producer? What if you have no way of knowing what their vision was? What if current technology allows you to achieve greater clarity, dimension, or dynamics?

JB: I think greater dynamics are very seldom achieved. Maybe once in a while. We all sadly know the trend there. If you are working on material from the '80s or earlier, the dynamics are probably pretty good – try to preserve them.

MR: In general, if our mastering tools allow us to better express the originally intended vision, overcoming limitations that may have been present at the time of the original recording, then hopefully we are doing some good for everyone. I don't think we need a letter from the artist or producer to know what their vision was. Once the aesthetic is established, it's there no matter what. We can hear it and feel it instinctively.

JB: Choose your perspective and stick with it – defend the original sound, or improve the original sound.

JT: Remastering pet peeve? I'll go first! Bad tops and tails, especially on bootlegs made from LPs.

MR: Vintage tapes with print through, incorrectly labeled sources, and working on a record with one or two extremely over-compressed mixes on it.

MG: Too much broadband noise/hiss reduction. I really do not like this. There's a smearing or underwater sound that happens if this is used inappropriately, in even small amounts. It's like MP3 artifacts, multiplied by ten. Yet I hear it so often.

JB: Other than the eternal battle of fighting drifting cassette tape azimuth, it's clients and/or labels trying to transfer analog sources themselves in order to save money. Then we receive crappy files – sometimes even MP3s – of cassettes or open reel analog tapes being played on terrible/neglected machines, uncalibrated, wrong Dolby settings, wrong format (playing a quarter track tape on a 2-track deck and not realizing it, etc.). The biggest disaster is someone foolishly trying to play analog tapes that need to be baked and totally ruining them. Have fun confessing that to the artist who handed over their life's work of tapes to you. You should have let me do it. Even I know my limits – if I get an obscure format or a really damaged tape, I'll tap out and take it to a place like Sonicraft [Tape Op #60] who specialize in restoring and transferring every kind of open reel analog tape, and more. They are a major asset to us all – be glad they're around. On the consumer side, there is this two-part assumption that annoys me: 1. There are original analog tapes for everything. 2. These holy grail analog tapes are the perfect, pure sound that has been withheld from the public until now. Both of these assumptions are false. There are not analog tapes for everything, and they do not always sound good. I understand the marketing reason for stickering "From the Original Tapes!" on the LP jacket, but it's getting a bit silly. We're reissuing projects from the '90s and early 2000s now. A lot of those were mixed to DAT, not analog tape, and that's just the way it is. I have yet to see a "From the Original DATs!" sticker on a LP. I dare someone to do it.

JT: I've remastered from original DATs, and even MiniDisc! Any advice for aspiring mastering and/or restoration engineers?

MG: Listen to as many different kinds of music as you can. Be open to every genre. Make sure you enjoy detail work.

MR: Diversify your approach. A little of this and that – for restoration, this could mean combining analog and digital cleanup. For mastering it could mean mixing up dynamics processes and types of EQs, combining hardware, software, digital, and analog. Embrace simplicity and diversity.

JB: Take the time to really learn software restoration tools – in your own DAW, with iZotope, or whatever. This is actually something you can practice – do some of your own vinyl and cassette rips, then restore and remaster them. There is an infinite amount to learn about phono cartridge and preamp combinations, stylus types, tonearm geometry, turntable drive mechanisms, and more. All this is a deep well. Study up on various older noise reduction units used on analog tape machines. Read a Dolby SR or A manual – that technology will blow your mind.

JT: I'll wrap this up with my advice: learn to listen to, and love, noise. Heed the wisdom of Coco Chanel, whose famous fashion rule was to remove one accessory before leaving the house. Apply that to audio restoration: hone in on what you think is the right noise reduction setting, and then dial it back one tiny click. Maybe you'll go back later and take out a bit more noise, but I swear by this rule. It keeps me from inadvertently being heavy-handed when I'm deep in the zone.