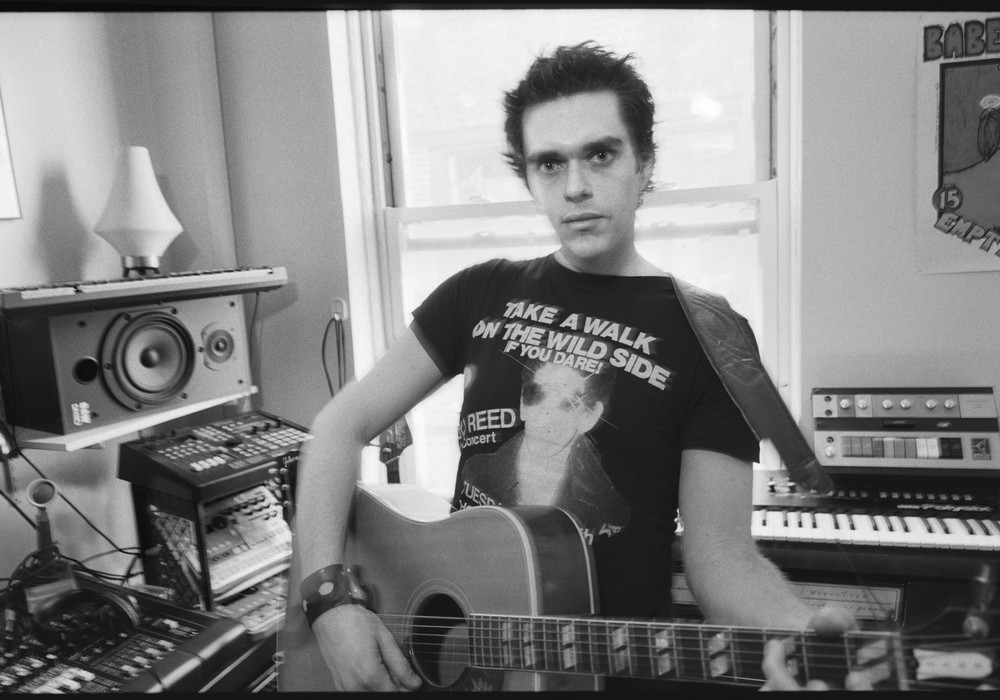

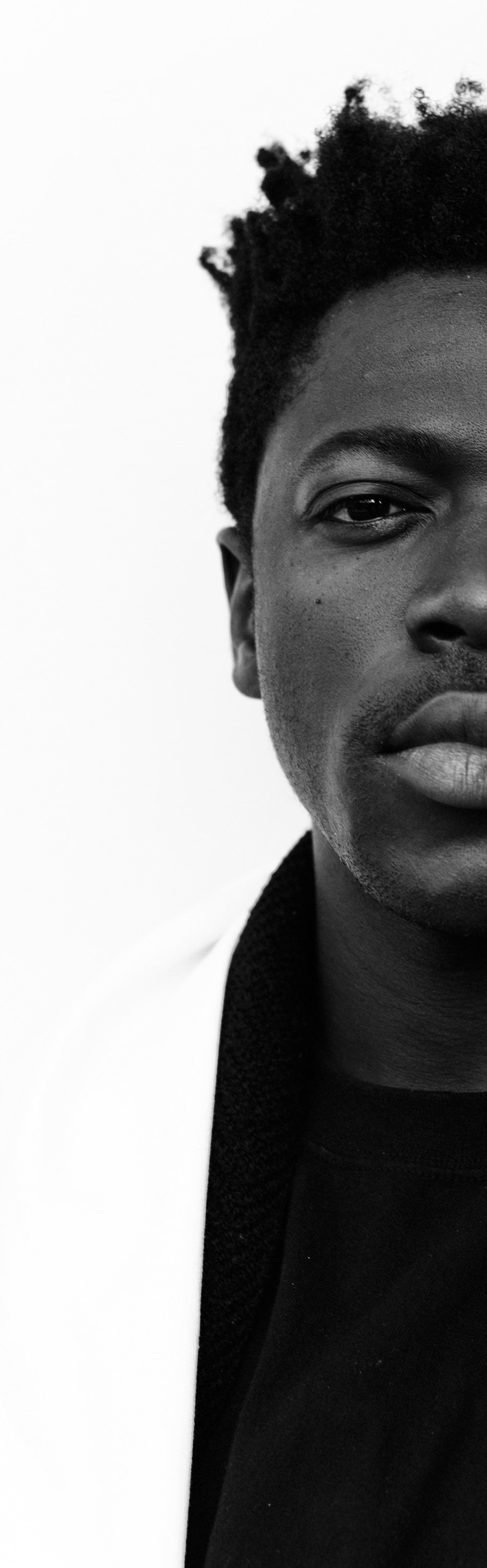

If music lives in the spaces between the notes, consider Moses Sumney your guide through the stillness. A relative newcomer to the scene, his live shows in Los Angeles attracted an impressive list of fans from the music elite. He has performed with, and alongside, artists such as Beck, James Blake, Dave Sitek (TV On The Radio), Solange, Erykah Badu, Sufjan Stevens [Tape Op #70], St. Vincent, Junip, and Local Natives. Not bad, considering at 20 years old he noticed his friends were "doing things" and decided he needed to "do something" as well. Mission accomplished. His latest release (and first full-length album), Aromanticism, is a refreshing listen, full of great songs with engaging production featuring his otherworldly falsetto, and, of course, plenty of spaces in between the notes.

Your earlier work was quite stripped down. I was curious about your transition from those records you did on 4-track cassette recorder to making Aromanticism?

Definitely. Aromanticism is my first full-length album, so it's the debut album with two capital letters. Before that, I had two EPs, the first being Mid-City Island, which was recorded entirely to 4-track.

You got that from Dave Sitek?

Dave Sitek, yes. In 2013 I was starting out in L.A., playing a lot of shows. My name spread really quickly amongst "industry types," so I was meeting producers like Dave Sitek. I didn't really know what I wanted to do, production-wise. I didn't know how to produce, or how to approach sonic design. He said, "The best way to figure it out is to record yourself." I had never done that before, somehow, so I went up to his house and he showed me this 4-track recorder, a Yamaha MT4X. It's what they recorded the first TV On The Radio on. He made a video of him using it, so I could reference that. He gave me homework, like, "Record some demos and bring them back to me." I went home, back to my tiny studio apartment in mid-city, and I recorded a bunch [of songs] on the floor of my bedroom. I had a little [BLUE] Bluebird microphone and this shitty little amp. I really didn't know what I was doing. At the end of the process I realized I loved the music so much. Not just the music, but also the recordings. I've always been a big fan of lo-fi, unprofessional recordings. On a whim, I decided to put it out as a free download. Because I was meeting producers at the same time I was making those 4-track recordings, there was a lot I started making for the album way before that first EP came out. I always had the idea, or vision, of the album in my mind in the years leading up to its release. I knew it would be more polished, and that there would be more computer recordings. I wanted it to be more fleshed out, instrumentally; but I also knew that I didn't have any money, so I didn't really have a way to make that. There's "Man on the Moon," one of the first songs I put out. It's on Mid-City Island. I started making a studio version of that. I thought it was going to be on the album, but I ended up cutting it. It's a studio version of it with a drummer; Thundercat [bass] plays on it. There's a string section and all this production. Then I turned around and made the 4-track version of it. The album Aromanticism starts with the track "Man on the Moon (reprise)," which was initially the reprise of the studio version of "Man on the Moon." Then I ended up cutting the full song and keeping the reprise, because I liked it as an intro to the record, [as well as using it as] a connecting piece to that EP. It was always the plan to do music that was more fleshed out, but it took me a few years to do it.

You've talked about your first record being "purposefully incomplete." I thought that was an interesting idea.

Yeah. It was really necessary for me to learn how to get out of my own way, get out of my own head, and learn how to put music out. I was so used to not putting music out and dreaming about it. When I started making it, it was so intense for me to put anything out. I would work songs into the ground. I was beginning to fear that I would never release music. Pretty much as soon as I started playing shows in L.A., it became a moment and people became very aware of me. I wasn't expecting that. I was expecting to have a really slow beginning, spending years honing things. It worked the opposite way. I got a lot of attention off my live show before I had really put music out. Suddenly there were all these people waiting to hear something. Because I came up in Los Angeles, a lot of these people were industry people. I think that really affected me negatively. It made me really intense about everything. It felt like a really big deal. When I made Mid-City Island, I realized the best way to combat that was to release whatever. I had to learn not to be precious. There's a song on there, "Mumblin'," that's completely improvised that I only did once. I realized that I needed to learn to be free. "Here are my demos. This is my first project."

There's such a great spirit to the recordings that have you sitting in your room making something without someone looking at you through the glass.

I really do think it's the most honest, and I'm probably most drawn to music that's like that. Out of everything I've recorded, that project is still my favorite. I think if the emotion is intact, that's the biggest thing.

On Aromatacism you worked with Matt Otto, Joshua Willing, and Ben Baptie. How was that to work with people and trust them with what they did?

Working with those people who ended up on the record was amazing. All of them. I had a wonderful process. The thing to keep in mind is that between 2013 and 2017 – when the album came out – I worked with a lot of people, and a lot of that won't ever see the light of day. Before I got around to working with those particular collaborators, I had gone into studios with bigger producers, doing the rounds a little bit. I knew how much I hated working with people.

Did you feel that the music was changing by working with different people?

I felt like people didn't respect me or my opinion, because I was so new and didn't have much technical knowledge; and because they were regarding me as just a vocalist. When I'd get in the room with people, they'd be like, "Yeah, sing this certain thing." I'd say, "Hey, what if we make the drums like this?" They'd say, "No." It was quite difficult in the beginning to get people I was working with to take me seriously. They'd like my voice, and then want to sculpt it in a way they thought was fit for it. I learned early on to run away from those people, because I want to have creative control over my own work.

Who was driving that?

Sometimes I'd have a meeting with a label, and they'd ask if I'd met a certain producer. I'd be down, because I didn't know what to do. I got to a point where I was really desperate, and at my wit's end. I didn't know how I was going to make the record. Then I realized that I had to do it myself. In the beginning I thought I'd bring in a producer to work on all these tracks I wrote. We'd have a beautiful record together, and skip off into the sunset. I realized that, one, because I was so interested in different types of sounds and instrumentation, there was no way that one person could do everything I wanted. Two, in order to maintain control, and feel like I was growing as a producer in my own right, was to start on my own and handpick people to come in and do very specific things. That's how I ended up making the record. It really was an intimate, one-to-one thing with all of the collaborators and co-producers. Josh, especially, who worked on almost every song – at least in an engineering capacity, and then in a production capacity on a couple. The story of how each song came about is completely different.

I was curious how much of that 4-track intimacy and honesty carried over into this record.

Quite a few things. On a broader scale, the idea of being really emotionally honest and intimate. That was something that I realized needed to carry on through the work, regardless of what the production was. The honesty of the 4-track and the personal nature of it [was important]. Shockingly, to me, I didn't use that 4-track on the album at all. I used it while I was making it, but none of it is on the album. Something that stuck with me was bouncing to tape. When mixing, we bounced everything to tape with Ben Baptie. I think the early 4-track work made me obsessed with that process, and with the graininess of tape.

Were you bouncing all the tracks,

or were the mixes to tape? Or were you talking about limiting yourself to tracks and doing sound-on-sound that way?

It was really in the mixing process after we'd recorded everything. We went track by track when mixing to a reel-to-reel that Ben has. What else stuck with me? Sending my vocal through an amp. That's something I was doing in the 4-track days that carried over to the album.

Is that on "Don't Bother Calling"? Is that an amp vocal?

That's tape. The effect on that is tape. I don't even remember what we sent through the amp, honestly.

Loop pedals are something you use a lot.

I've used it in a live show with a band also. People always assume that I recorded using loop pedals on the album, but I didn't. I did a lot of multitracking; a lot of vocal layers, but they were pretty much all individually [created] without utilizing a device. In the live show I never stopped using a loop pedal. I built out the live shows in the early days when it was just me, a guitar, and a loop pedal. Now it's me and two or three other people, but I still utilize it quite a bit.

You did all the vocals on the record?

100 percent me.

They're awesome; beautiful and orchestral. Not a traditional approach to background vocals. Were you asking for more tracks? Were you experimenting and finding it?

That's exactly it. I can do prearranged writing, but I found on the record that most of, if not all, the vocal arrangements are on the spot arrangements. "Give me another track." I love it.

There are probably parts you wouldn't have come up with on paper.

Well, I also don't know how to notate. So that would have been interesting!

Aromanticism is very psychedelic and cinematic at times. You've mentioned you wanted it to have a "pre-sleep" quality.

The main trick, and the main challenge, was not dousing everything in reverb. You think "dream state," and suddenly it's, "Oh, let's make it sound washy and confusing." I think there are multiple things. Maybe the biggest way I found to execute that was to be free and adventurous. With songs like "Don't Bother Calling" or "Make Out in My Car," I was letting the melodies linger and take left turns when they wanted to, instead of trying to feel too structured or too repetitive. I think a facet of dreaming is that you never know what's going to happen next. You turn and you're in a new scene. I think I needed to first and foremost let the melodies do that how they saw fit and go to weird notes when they wanted to. In the production, it was allowing elements to come in and out in a similar way. We ended up doing a lot of sound design, which is my favorite.

So are you starting the tracks with click and guitar? What's the seed?

It's really different for every song. For "Don't Bother Calling," I played a bass guitar. That was just bass and vocal for a long time, and it mostly still is. Then, at some point, I added the vocal swirls in the beginning in order to mimic strings. Later I got Rob Moose [Bon Iver] to play strings. We had a long conversation about making it feel like a dream; making it feel like things were drawn out, like gum being pulled, so that you lose track of time, especially if you're listening to the strings. The vocal layering came in somewhere in the middle. With a song like "Doomed," I wrote that with Matt Otto. He played a synth and we executed that by adding a noise track; having it barely there so that you feel it, but don't notice it. Then it swells and grows as the song moves dynamically. With that song it was, "How do we move this without adding too many more elements, like drums?" At one point there was a horn arrangement.

There aren't too many drums on the record.

There are very few drums.

But when they happen, like the hi-hat coming in on "Lonely World," you notice it.

One thing I'm grateful for about being a solo artist is that if you start with just yourself, you never have more than you need. I was in a band in college; an indie rock band. There were five of us. I'd always be like, "Okay, what should I do on this part?" But you don't need to do anything sometimes.

There's a lot of space in this record.

Thematically I was exploring isolation, loneliness, and emptiness in a lot of ways. Not permanent emptiness, but the idea of a void. I think it was important to reflect that musically and not do too much. With the lyrics the question became, "How much can I get from saying the least?" A lot of the music I've released has been experimental in form, because a lot of the songs I write are often long and really lyrical. It can take a long time to get the point across. "Plastic," especially when I first wrote it, was a challenge to write a short song with just one chorus. The point is that every time you repeat a line, it hopefully has a new meaning. Maybe the first time I say, "Notice you're not listening," it means something different the second or third time. There's such a power in reemphasizing something. The challenge with performance and production then becomes how to reemphasize something without it being redundant. With "Plastic" it was saying that line over and over again while allowing the music underneath it to morph. I think it changes key. It's the same sentiment, but hopefully everything around it colors it in a new way. It was the same with "Make Out in My Car." There's a double vocal, then a harmony, then it's sliding up, and then a new drum thing you don't notice coloring the world around it. The music is part of the lyrical intention, and I'm trusting the listener to be able to fill in the blanks. It's risky, but for me as a listener it's so fun listening to a song that doesn't have harmonies. As a listener, I'm always singing the harmony. I wanted to not take that joy away from the listener. Sometimes what's imagined is so much better. Leaving space for the adventurous listener to let their mind go off is so important.

Walk me through the track "Quarrel." The tune ends in one spot, and then you get this incredible Stevie Wonder / Radiohead moment.

It was such a long process! For me, all the songs start with the music and not the lyrics. I worked with Cam O'bi on that. He's a wonderful producer; he works on mostly hip-hop and R&B. I was really quite reluctant to work with him in the beginning, because I thought, "I'm not making an R&B record. Why should I work with an R&B producer?" It was a rare situation where a manager set us up. I did it to try it out, and we made that song. That started with a little drum machine. Cam produces everything in Fruity Loops [now FL Studio], which is so amazing to me because he's done J. Cole and Chance the Rapper, but it's entirely on Fruity Loops. We found the chords; I took it home, and I could feel it being a lot of things. It was a lot slower, at first. Sleepy is fine with me; it's where I mainly live. But it was also courting the R&B world with this really steady beat, and the chords. I wanted to fuck that up. I was listening to a lot of Joanna Newsom at the time, and I was really obsessed with harp. I knew I wanted a jazz harpist, and I could not find that anywhere. We found a harpist on YouTube. I found her Facebook and looked through her friend list to see if I knew anyone she knew. I found someone, had them do an email intro, and a few weeks later I flew out to New York to record her in Harlem at her house.

What's her name?

Brandee Younger. I really suggest you look her up on YouTube and watch anything of her playing live. She did an NPR Field Recordings video that's excellent. I truly believe she's the best harpist in America. She's got a classical background, but she shreds on jazz. We recorded a ton of her playing harp, and took that back to my house. That was such a crazy experience. When we started making this record, I didn't know how to use software at all. I basically learned how to use [Apple] Logic over the course of it. Because Cam only worked on Fruity Loops, he couldn't edit the harp. He was like, "I think you should do it." That was my first time going in that deep on an edit. We had so much harp.

Was she tracking to the tune or playing free?

We had her do chords and predetermined parts, and then she improvised a ton. I think most of what we used were her improvised parts; I took her best bits and made them into parts that were more consistent. I knew that I wanted a long song on the record. I also wanted a song that started with a beat to move into the live realm. I was really inspired by this Jill Scott song, "Talk to Me" that transitions from being studio to totally live in the middle. I always wanted to really explore that, but go way more psychedelic. I knew I had to pay homage to Stevie Wonder in some way. Everyone must pay their due. Quite a while after we started the tune, I assembled a band. We got into a studio with Paris Strother, who plays in the band KING. I sat with her, and we constructed the chords of that end part. We also recorded it as a trio with bass, keys, and drums. Then I had her play all the synths at the end, and the piano outro as well.

There's so much great arrangement, in terms of countermelodies with the horn parts. Actually, I don't know if they're horn parts.

It's guitar with distortion and an octave pedal.

It's very cinematic.

I'm glad to hear you say that because that was a lot of micro-production; a lot of part by part. "Okay, this thing comes out here, and this falls out, and this enters here."

It's funny to hear you talk about things that are "incomplete." That one doesn't feel incomplete to me.

I think in order to communicate that the minimalism of the record is intentional, there had to be maximalist moments. There had to be the explosion at the end of "Lonely World." There had to be both climaxes in "Quarrel," so that when we get to "Indulge Me," and it's just guitar and a vocal, that's very on purpose.

And it shows that you cared about making a "record" instead of recording songs.

Yeah, definitely. It had to be an arc that went all the way through. When we were "picking singles," the label asked, "Okay, what's the second single?" I said, "There are not any singles." I was being so difficult. I feel like a lot of songs don't stand up on their own, honestly. It's all meant to be listened to in context.

So when you listen back to Aromanticism, is it as you heard it in your head?

I don't know. I think that maybe 50 percent was as I heard it in my head, but there's no way I could have imagined what would happen. I think "Doomed" was probably as I heard it in my head. "Lonely World" is as I heard it in my head. But "Quarrel" and "Make Out in My Car," I never could have imagined those sounds. I feel like there's so much more I can do now. The thing that surprised me, pleasantly, is how people are saying how cohesive the album is now. I was worried when I was making it that all the songs were completely unrelated and everything was such a different genre. I think part of what made it feel so cohesive is mixing.

How much ended up on the cutting

room floor?

I'd say in terms of finished songs, there were probably seven or eight that I cut in the last month of making the record; the last month of a three-year journey, right before mixing. I really did think the album was too short. In that last month of making the record – where we had mixing dates set and I had my deadline in order to release it last year – I was writing all these songs, and suddenly we were producing very quickly and wrapping up. I brought in new collaborators, and it was a bit insane. There were probably seven or eight songs that were cut; finished songs I'd been working on for a while.

Would you revisit those and rework them for a future release? I know you've got music that has traveled from album to album.

Yeah. I love the idea that a song is a story that can be told and retold. I've gone back and assessed all of it, and I'd say half of it I want to work on and then put out.

The re-telling of a song or story is an interesting idea.

I've always been a fan of versions. I remember being a teenager and listening to the first Grizzly Bear album [Horn of Plenty] that has a song "Shift" on it. Then they became a band, and years later they did an acoustic guitar version of it. To me, those are entirely different songs. I love and I hate the idea that a piece of art is never finished, but you stop working on it because you have to. Given the chance, you can go back and tell that story again. I loved when R&B remixes in the 90s and 2000s became such a thing; when someone would completely remake a song from the ground up and ask, "What if it were this way?" I find that so inspiring, and I think that a song never stops giving.