I still remember my first experience hearing Taylor Deupree's Northern on a winter night back in 2007. Reaching into a stack of borrowed CDs in my apartment, I randomly selected a disc for some musical accompaniment while washing the dishes. The album began so stealthily that it took 10 minutes of half-listening for me to register anything in particular about the music, other than that it was quiet, ambient, and glacially-paced. However, as the record progressed, I became increasingly aware of the delicately arranged layers of sound casting an extraordinary spell over my apartment. Compelled to sit down and listen more deliberately, its microscopic gestures began to take on greater magnitude. Now I could clearly hear it was brimming with a previously hidden world of emotion, intentionality, and color.

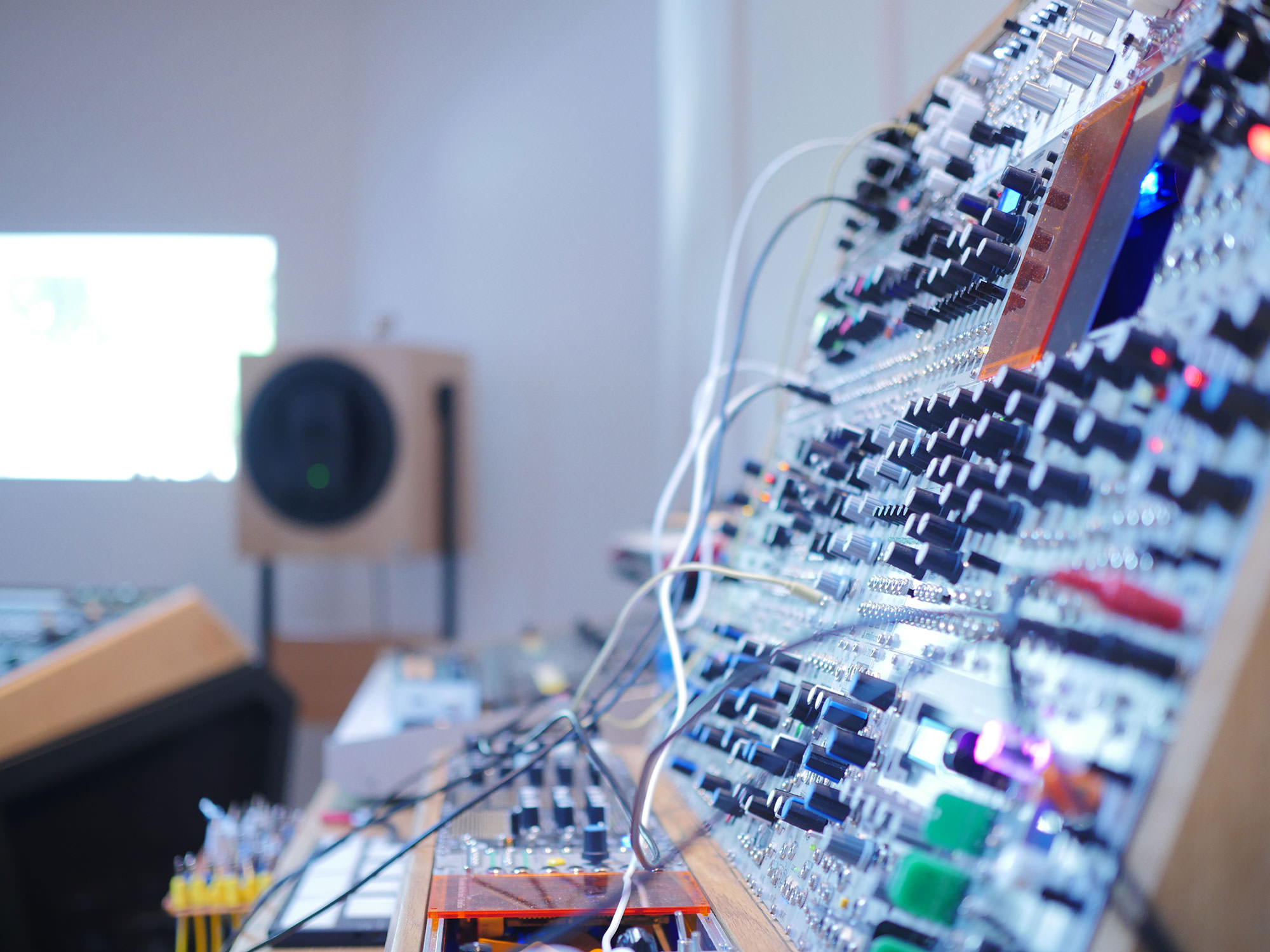

Deupree has been honing his signature "microsound" style, which incorporates a wide variety of acoustic and electronic sources, for over 20 years. Hardware and modular synthesizers, electric piano, acoustic guitar, percussion, tape loops, guitar pedals, and field recordings have all found a place in his oeuvre. In addition to his solo albums and numerous collaborative recording projects, he is also the founder and curator of 12k, an experimental record label started in 1997. The label has, in many ways, defined the contours of a new sub-genre, releasing over 100 records by some of the most notable practitioners of the art form from around the world. In 2005, Taylor and his family relocated from Brooklyn to a rural area north of New York City. There he constructed a studio space behind his home, filled with natural light and views into the surrounding woods. In addition to serving as his creative workspace, the studio was designed to function as a full-fledged mastering room – a role which Deupree has increasingly taken on for both 12k releases, as well as those of other artists seeking his attention to sonic detail. I visited Taylor at his studio on a beautiful summer afternoon to discuss his many activities, interests, and inspirations in music production.

It's rare for someone to be equally well known as a musician, record label founder, and mastering engineer. You are also active as a photographer and graphic designer. Is there a hierarchy or natural order among these roles?

Making music is just what I do; it's why I'm here. I feel like if I could do nothing else, it would be that. It's how I express myself. Mastering is really my day job now, because in today's music environment it's harder to make money writing music. Mastering can pay my bills, and I like to do it. I was always a very technical person. The label was started 20 years ago to fill what I thought was a certain creative gap in small American electronic music labels. It probably takes the least amount of time, because I've dialed in the process. I'm not doing a ton of releases; just a few a year. Most of the work involved is online; communication, production, and promotion. Mastering I have to do every day, because I have clients waiting for me, as well as deadlines. My own music, unfortunately, is the first thing to get pushed to the side, even though it's what I want to do the most. So I have less time to do my own music – but still enough time. The three are often combined, too, because I master most of the releases that come out on the label. I offer that to all the artists, as well as the graphic design for the album covers. That helps keep costs down with the label as well, because they're important services I don't have to pay someone else for.

How do these different roles play out on a day-to-day basis?

It's tough, especially with family and kids. I'm sure lots of artists my age have this trouble, when you have a family life and all these different professional roles you're trying to play. I never wanted a regular 9-to-5 job, so I've always done whatever I needed to do to make that possible. I love every minute of it. My day-to-day work time is largely spent mastering or doing label tasks, such as shipping orders or overseeing some aspect of a new production. There will be design or photography days, when I'm working with an artist on a new release for 12k. It really comes down who needs what the soonest, and I usually prioritize that way. It can be tough squeezing things in, but I manage to get all of it done. There's a lot of variation in the things I do, and I have to balance my studio to be ergonomic for both mastering and writing, as well as to be able to sit at the desk and work on label management.

Do you have to explicitly set aside time for your own work?

One thing I started doing last year is what I call "no-mastering Thursdays," where I just spend the day in the studio messing around and working on my own music. I had to make that time. Usually I work on an album of mine until it's done; then I take a break for a while, and then do another album. I've recently released an album [Somi]. When I'm in between projects, and nothing's pushing me to get something done, I tend to get a little lazy, except for just messing around – making sounds or something like that. Yesterday I had 20 bells out here, a mic, and a looper, just making cool loops. I record it all and I keep folders on my computer of 3- to 5-minute passages. They're going to be fodder for an album or something down the line. If I can get someone from out of town, like Marcus [Fischer] or Stephen Vitiello, in for a few days and we're working on an album, that's great, because it's just time for that. I'll tell my clients, "I'm not going to be able to work these days." Collaborations always go more quickly than working on solo recordings.

What made you decide to move your studio up here from Brooklyn?

On a...