Dan Auerbach, along with drummer Patrick Carney, started The Black Keys in 2001 as a writing and recording project, releasing their first album in 2002. Dan also began recording and producing other artists along the way, initially with musicians like Jessica Lea Mayfield, Patrick Sweany, and others. Big changes arrived for The Black Keys in 2010, when the album Brothers and the single "Tighten Up" sold millions of copies and garnered three Grammy Awards. Dan moved to Nashville around then and opened up his Easy Eye Sound studio, a place filled with the best vintage and new recording equipment that is also home to many fun instruments. Sessions for The Pretenders, Dr. John, Shannon & The Clams, Lana Del Rey, and many more have gone on here, so I dropped in to hang with Dan, and his engineer Allen Parker, to learn more about his career and thoughts on producing records.

With The Black Keys, I remember hearing that your early albums were really DIY. Did you guys take recording into your own hands from the beginning?

Oh, yeah; totally. That's what we did. The first time I ever saw a cassette 4-track was at Pat's house. That's what we started on, the Tascam 4-track. Then we had a [Tascam] 388, as well as a little digital multitracker. We also had some shitty reel-to-reel machines. Yeah, we always were building a studio and recording ever since I met Pat.

It seems like that went hand in hand with the band, to a degree.

It started as a recording project. We both loved recording, goofing around with the 4-track, and making mix tapes. We'd never played a show, but we sent one of our mix tapes to some labels, and we got a record deal! Then we got a review in Rolling Stone, and we'd never played a show. It was all the recording thing, at first. Then it was like, "Oh shit, we have a record now. I guess we gotta go play shows." That's how it all started.

Did you have to gear up for shows?

Oh, yeah. We were not good at it, at first. We had about 30 minutes of material, and we did it in about 15 minutes. Just flying through the songs. I remember our first show we played at the Beachland Tavern in Cleveland. I was pretty much totally blacked out the whole show. I don't remember anything.

That's crazy. What was the evolution, after the 388 era?

Well, we loved the 388. We did the second record [Thickfreakness] on a 388, and then we got the Tascam 16-track, with a huge Tascam console that Pat bought from Canada. It was Loverboy's old console! We rented a room in the abandoned General Tire factory in Akron. The whole building was vacant. When we were done, we left the console in there. They demolished the building with the console inside of it.

Wow, Loverboy's history!

I know where it's buried. Then we went to Pro Tools. I had [iZ Technology] RADAR, which I really loved. I love the sound of it, and I loved working with it. I think some of the best sounding recordings I ever made were on RADAR.

Did you feel any remorse in stepping away from tape at all?

No, I never felt any allegiance. But you could hear a difference in each little format. Each tape has its own particular characteristics. Tape is cool when you've got a great band that can play live; but with most bands it takes a little work, and Pro Tools makes that a little bit easier to deal with.

When was the first time you guys worked at an outside studio?

We made four records on our own. Then we did our fifth record [Attack & Release] with Danger Mouse [Brian Burton]. That was the first time we ever used a producer, and the first time we ever recorded in a real studio.

What studio did you start out at?

It was a place called Suma [Recording Studio] in in Painesville, Ohio; Ken Hamann's place. Paul Hamann was there running it. Ken had passed away [Tape Op #13]. It's still the coolest studio I've ever been to. It was the first real studio I'd been in.

Pere Ubu had done many records out there.

Pere Ubu, and Grand Funk did their records there. Ken Hamann was a distributor for Gotham Audio. He supplied Motown, and all these different places, with their parts for consoles and all of their machines, as well as all the cables. That was all Ken. He went up to Motown to help them set up their console. Just a history of amazing audio.

Didn't they have a custom console in there?

They've always had custom consoles. They started at Cleveland Recording. Cleveland built their own tube consoles, which were fucking awesome. But then they built their own 36-channel split console; the first ever graphic EQ. It was pre-API and pre-Sphere. It didn't have frequencies on it; it had [musical] notes that you changed. Big, long-throw Gotham faders on it. Just beautiful.

Is that studio still around? What's happened with that?

Sadly, Paul passed away. The whole place was caving in. It was run down, and it's in the middle of nowhere. The lake is right there, so in the wintertime there's all the lake effect snow. It's a hard place to run a business.

Yeah. It's too bad. We did an article with them ages ago.

God, I loved that so much. I learned so much in there.

Was that just for Attack & Release, or did you slip in and out of there multiple times?

That was just for that album. I had gone and taken a tour before, because I'd heard about it. I wanted to meet Paul and learn about the studio. We made Danger Mouse go there; totally out of his comfort zone. He never works without his engineer, who's like his right-hand man. It's part of his flow. We totally got him out of his whole routine. We made him go to Painesville and use the in-house engineer who wasn't lightning fast with Pro Tools. He was an old tape guy.

How did you end up working with Danger Mouse?

Pat met him hobnobbing in L.A. They sparked up a conversation. Brian mentioned, "If you guys ever want to have a producer, let me know. I'd love to work with you." Like I said, we'd done four albums by ourselves. It was like we'd had enough of ourselves. It was time to open up to a new experience.

What was different about that for you guys?

Well, I mean, we'd been so insular that it was almost unhealthy. I think that if you're trying to be like The Shaggs or something, it's okay to stay in your basement. But if you really want to learn things, enjoy yourself, and get into it, you gotta work with people. You have to open yourself up to the experience, and let yourself be comfortable with working with somebody else. That was the first time we'd ever done that. And, you know, we sold four times as many albums. We started our relationship with Brian; and it was cool, man. We worked with Paul Hamann, so we knew what Neumann mics were supposed to sound like. We had a frame of reference.

The relationship with Brian continued?

Yeah, we did a few records with Brian. We clicked with him. Got along. It was fun.

When did Mark Neill [Tape Op #29] join the mix?

Mark Neill worked on Brothers. I'd been a fan of Mark's records for years. I bought this Toe Rag [Studios, Tape Op #15, #88] record by Ronnie Dawson [Just Rockin' & Rollin']. It's fucking badass. It's a great record. It sounds incredible. I went to meet Liam [Watson, Toe Rag owner and engineer] when I was there, because I wanted to see his studio. It's such an awesome place. Then, as I started to look into Toe Rag, I realized Mark basically had built Toe Rag in the '80s in California. Same color scheme, same tape machines, same console, and same concept. I reached out to Mark when we were on tour in San Diego, and I went to his studio and cut something with him. I don't know if you've been to Mark's studio in San Diego. He built it in his two-car garage, in a little mid-century home. It's the size of a fucking closet, but he would make things that sounded huge, like Capitol Records or something.

He's really studied recording.

A lot of people talk about gear, but he's the only person I've met who actually has firsthand experience of what it does. He's never steered me wrong. Any time he ever gave me a sonic recommendation, it was always right on the money. Yeah; he's a talented dude.

You were doing mostly a tracking session with him on Brothers?

Yeah, we decided to get out of town. We went down to Muscle Shoals [Sound Studio], another studio that I was interested in. We got in there, and it was like a shell of its former self, right? There was nothing in there. It used to be called the "Burlap Palace," but it was all fucking plywood. Black plywood everywhere. No console, no nothing. We'd brought all of our gear, and Mark was engineering. He brought a couple [of old] Universal Audio preamps and a little Pro Tools rig. We tracked down there and cut a couple songs. It was great. We had a lot of fun. That's the thing that I learned about those places. It's all about who's in them. You know what I mean? As much as I love all these old studios and all this old gear, none of that really matters unless you've got those people in there.

They had those musicians.

Like Spooner [Oldham], and David Hood, and Jimmy Johnson [Tape Op #26]; all these guys.

I saw them all play together recently. You hear that finesse. It's amazing.

It was fun. We had a good time. Pat used Mark's old Gretsch kit, which sounds incredible. Two mics on the drum kit. I'm playing a little speaker, and we tracked the whole record in like a week. Then Tchad Blake [Tape Op #16] mixed it, which was cool. I thought it ended up being a really great combination. Our songs had 15 or 18 tracks, total. Then we were sending it to his dude, who's used to having a bazillion tracks on a digital board.

It was like a holiday for him.

It was cool. I think Tchad got into it even more. I think it showed.

Wasn't Brian involved in that record too?

He wasn't involved in that, except for one song ["Tighten Up"]. After we did the record, we had another couple months before we had to turn it in. We thought, "Let's get in the studio with Brian and see if we can come up with a song." Explicitly, "Let's try to write a catchy song." It was our seventh album, and it was the first time we'd ever said to ourselves, "Let's write a catchy song." That had never been one of our requirements.

That sounds dangerous.

Sort of. But we were such boobs. We went in the studio with Brian, and we wrote our first radio hit. That changed everything for us.

Isn't that crazy? Did you have Tchad mix that too?

Yeah. He mixed the whole record. We cut it at a studio in Brooklyn because we were all in town that weekend. It was fun. It was like a whole other experience. The idea of writing a catchy tune became a fun thing to do.

It was such a shift for you guys too. You were our "secret underground band" back then.

Yeah, sure.

Was Tchad mixing at his private studio in Wales?

Yeah.

So was this the first time you had a mixing session where you weren't attending?

Yeah, totally. I was on the phone with Tchad every day, and we would talk really in depth. But it always came back sounding really cool, so it was working pretty much immediately. Well, actually it took a few days. A few different mixes. Then, once he saw where my head was at, he was off and running.

How much is Pat involved in the direction and mixing?

It depends. From record to record, it's different. Pat's mixed some of our records, especially some of the earlier ones. But, yeah; we both have equal say.

That makes sense. With Brian doing some of the later ones, does that open up doors for you guys to feel safer to throw crazy ideas around when you have a mediator? Someone else in the room, besides just the two of you?

We always felt pretty comfortable about it. But I guess Brian came from such a different place. He was so computer-based. He got us thinking differently about things that we already were doing naturally. I think it was the first time I realized that, for me anyway, it's really helpful to be around people who make music, because it opens my mind up.

When did you move out to Nashville to start this version of Easy Eye Sound?

I moved from Akron about eight years ago. I bought the building as soon as I moved to town. It was just cinder blocks. It was a call center. You could walk in the front door and see all the way to the back door.

Just empty space. What prompted your move to Nashville, at that point?

Well, I used to come to Nashville when I was a kid. My dad would bring me down here. We'd go to Lower Broadway and watch music, or we'd go to the Station Inn. My mom's family played bluegrass when I was growing up, so those were the first songs that I learned. It felt like someplace I always loved, musically. Then, when I got older and was touring, I'd hang out with friends every time I was in Nashville. I started to see it in a whole new way. It wasn't just a little tourist music spot. There are other attractions here too. It became the spot I wanted to go to. There's the most music that I felt a connection to.

It has good infrastructure too. There's so much recording going on here. You can rent gear.

It's incredible. If you run out of tape you can call somebody, and ten minutes later they're at your door.

You can't get that in Portland!

You can't get that anywhere in the world. I mean, really. Then there're all the musicians that live here; it's so deep. I feel so lucky to be in this city. Every other week I'm stumbling onto something, or someone, I didn't know before that's changing my world up.

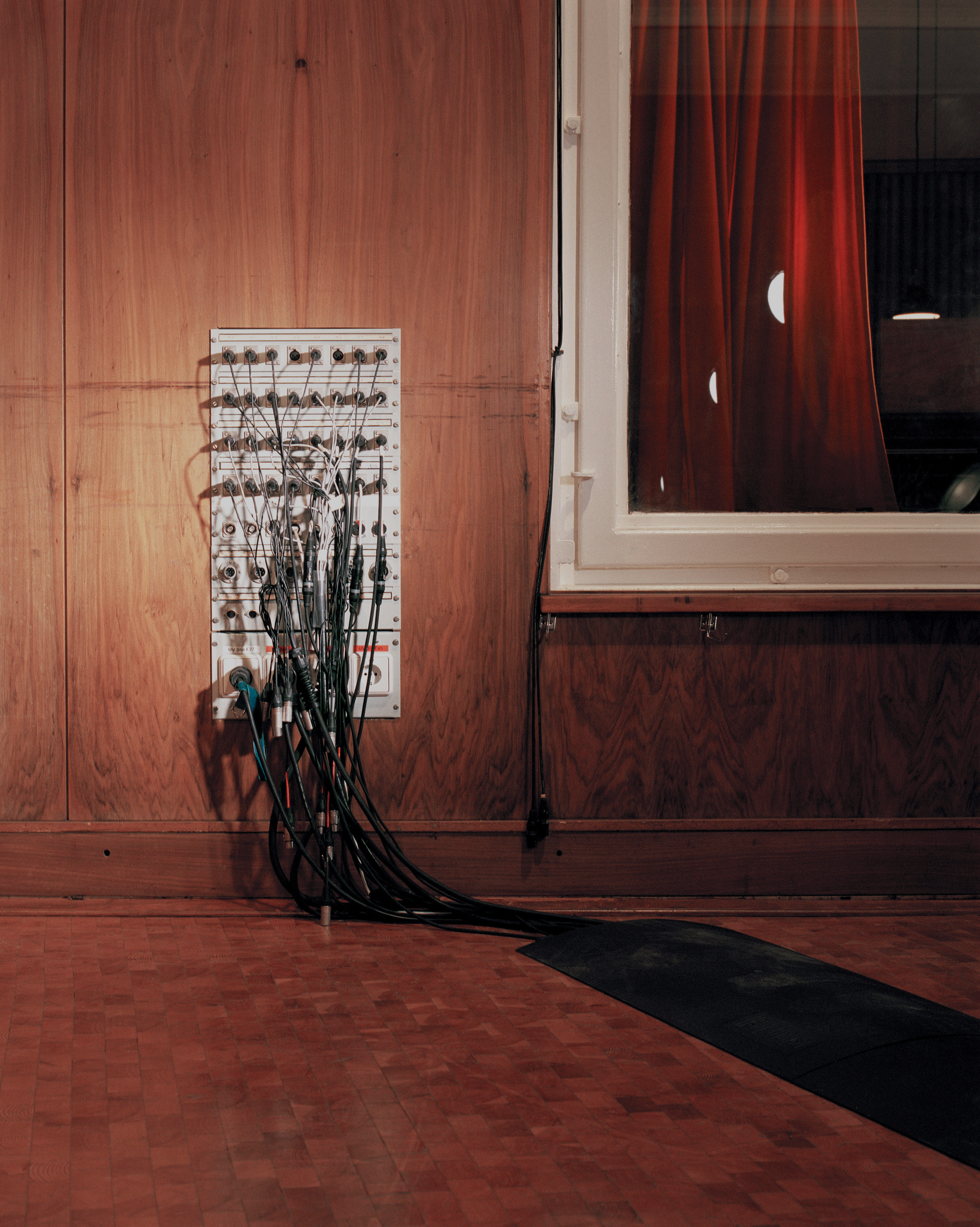

What was your vision for the Easy Eye Sound studio space?

I had Mark Neill help me. Basically I wanted a place that wasn't too big, that I could also cut live bands in. That was it. I didn't want anything huge. I've gone to all my favorite studios, and I noticed that most of them were small. Even the ones that were big, like Willie Mitchell's [Royal Studios], they made them small by making tiny rooms. That's what I went for. I wanted a place where we can have multiple keyboard players, multiple guitar players, drums, and cut live. That was the goal, really.

Along the way you started doing quite a bit of production. When I looked at the list, the actual amount of albums is impressive. That's a lot of activity.

Yeah. This is what I like to do.

What were some of the first productions you did outside of your band?

Bluegrass-type folks in in Ohio. People like Jessica Lea Mayfield. People that I would see in Ohio and be interested in recording. Or, you know, a band like Hacienda from Texas that sent me a demo. I thought it was really cool. I had them come up. They'd never seen snow before. They all showed up in cowboy boots, and three out of the four fell on their ass on the way to the house. Ill-equipped.

At that point did you have a space that you were using for The Black Keys and yourself for recording?

At first I used my basement. I had a back room in my house. I had Mark Neill come out and help me with the design and the equations. It sounded so good, it didn't make any sense to me. But that was that Mark Neill shit. Then I moved down here.

How does the label tie into that too?

Well, I'd been producing albums. I'd do a record and hand it off to a label. It's not like artists are necessarily coming to me. I'm seeking out projects, coordinating all the artwork, overseeing the photographs, and then I'm just handing it off to a label. I kept doing this over and over again. Then I thought it'd be nice to put it out myself, if I could.

How does the infrastructure of that work? A tiny staff?

Well, it depends. It's pretty cool. I've got a distribution deal through ADA [Alternative Distribution Alliance], and I've got a couple different deals. I can take a record to where it's best suited. I've got the Shannon Shaw record [Shannon In Nashville] that I took through Nonesuch Records, because I thought it'd be a good place for it. I've got a blues act that I'm doing, and a bluegrass act that I've recorded. I'm just going to take it straight through ADA. I've got a country kid, and I'm going through Warner Nashville [on that one].

Wherever it fits?

It's pretty awesome. As long as it's under the Warner Bros umbrella, I can navigate the album to where it's gonna be best served. It's a dream scenario. I only have it because I've met all these people and worked with these people for so many years that it's built in, I guess.

On the flip side, do you have people trying to hit you up and asking you to produce or be on the label?

Yeah. But I don't usually find acts like that.

I figured.

That's the other thing that's different for me. I've produced a lot of records, but because I make my living on the road with The Black Keys, I get to choose who I want to come in. I didn't have to worry about it being my living. I could get a little rock band that has no budget. I could get Jessica Lea Mayfield.

More picking and choosing, to suit your taste?

Exactly.

As a producer, I see a lot of times looking at the credits that you're usually playing an instrument. You're probably picking out backing bands for certain artists. How do you see your role as a musician and producer intertwining on the making of someone's record?

Hmm. I mean, I'm there to serve the song, in whatever way I can. If that's playing timpani, or playing a little bit of acoustic guitar, or getting out of the way and letting it happen... I'll be involved in whatever way it seems like it needs me. There's no really set rules or anything. But I do like it to be a collaboration. The last few times we've had a session, there's been three piano players, three guitar players, drummers, and vocalists; all live. There's a lot of collaboration. Everyone's working towards the same goal.

I always feel that the tidbits you can get back from great players makes everything better.

Like we said earlier about Muscle Shoals, or any of these studios, that's always been everything. The more that I'm in Nashville, and the more I meet these incredible musicians, the more I realize that, Jesus, there are a handful of people who are responsible for so many of my favorite records, and specifically so many hit records. Like I worked with this guy named Billy Sanford. He played the guitar on "Pretty Woman." He was [producer] Billy Sherrill's session leader for 25 years. He played on Top-10 hits in the '50s, '60s, '70s, '80s, and '90s. He's never not played on hit records. It's not a coincidence. All these guys are the unsung heroes of American music.

Well, your last solo record [Waiting on a Song] delved into that more.

Yeah. That's what we do here. When I work on records, I'll use those guys; whatever the project calls for. It's been awesome.

It's a treat to be able to pull in people who have been involved in such classic sessions.

That's part of the reason that it's so amazing to be in Nashville. I don't think there's more of those kind of guys in one area than Nashville.

You did a lot of co-writing on that record, which is probably something new for you.

It's the first time I'd ever done any of that.

That's like a Nashville thing, right?

Well, I don't know. If you looked at a lot of my favorite records for decades, it was like that. It was songwriters who wrote great songs. I don't know.

I'm not saying a "Nashville thing" in a deprecating way at all.

There's definitely a lot of that in Nashville, but it's also been the backbone of just about everything that's been great in American music.

I feel like that opened up some classic doors in your writing on that record. It's very different.

Yeah, [that was] after being with Brian and learning what it's like to arrange a pop song on a computer. Now I'm around guys who have to have the song stand up on just an acoustic guitar and a vocal. That's all they've ever done their whole lives. When I'm around Billy, the only thing he's ever done is played guitar on records. Now I'm hanging out with guys where the only thing they've ever done their entire lives is write songs. I'm there trying to learn what I can, really.

Do you feel like you're expanding, as well as trying to keep up?

Yeah, always.

I love that album so much, because it reminds me of bands like The Box Tops, where there was a strong producer element applied to a young pop band; that classic Dan Penn situation. Instead of going to a stylistic throwback of getting the "right sounds," you're actually going in through the writing and playing.

Yeah, we're not trying to sound "old." We don't put distortion on the drums. The reason that it feels nostalgic for you is because this is how records used to be made. It was a lot of humans making noise and getting it picked up on mics. There's a spirit there. There's a feeling. It's hard to explain, unless you've heard it before.

It's a classic mode.

Yeah. It's a good mode. I like it.

On a lot of your records, I hear lots of really cool, distinct uses of delay and reverb. What were some of the records from the past that inspired you with their usage, and what kinds of devices do you like using for those effects?

Um, I've bought and sold just about everything.

I had the feeling...

Mostly bought. Like the Binson Echorec back in Akron, when I didn't even really know how to hook it up properly. We've got four plate reverbs here, four different sizes; so they're all different flavors of plate. We've got tape slap. We use plug-ins. I don't know. I'm not so picky. Whatever sounds best. A lot of times the plate doesn't work. Sometimes it's too massive. We're EQ-ing this plate return so much. What's the point? Let's use a plug-in. But it's also like the more that you hunker down and work in the same space all the time, the more dialed in you get. You can hear something and know what reverb would work. I feel like we're to that point now. We know our limitations for our reverbs and shit. You know what I mean? There are some things I use a lot as well. I think it's just what it evokes. If you think about Lee Hazlewood productions, or you think of The Ventures, there are a lot of different sounds. There are classic Nashville vocal plates, absolutely. Shit, there're so many people. You know who I love? I got really heavy into Norman Petty and the sound of his records.

He was ahead of the world.

Oh, yeah. He was way ahead of everybody.

Have you gone to Clovis, New Mexico, to see Norman Petty Studios?

I haven't gone.

I've gone and made an appointment to see the old studio. It's just a trip. It's tiny.

Well, he had awesome musicians. He had his session musicians, The Fireballs. Those were his guys. Every time there's great music and cool sounds, you're almost certain to find that there was a crew there that hunkered down every day. Every single one. That's a lot like what we're doing here. We've got the same musicians, and we're here every day working. I'm here at 8:15, every day. We work all day.

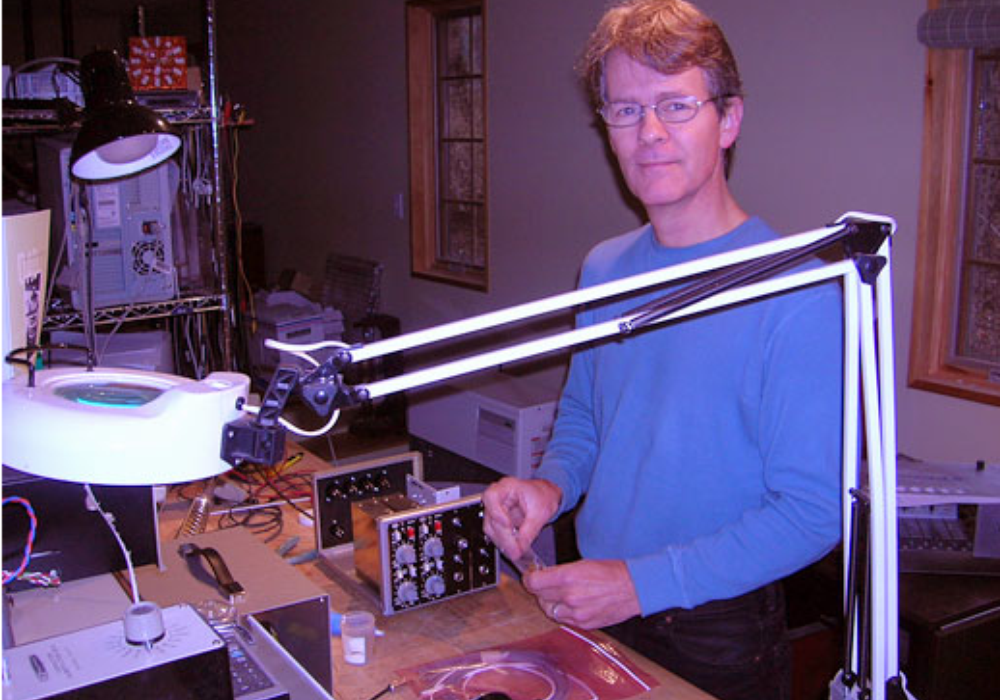

What gear choices did you make when you put this place together, like the console and all that?

I went with Spectra Sonics [Tape Op #102]. Well, that's not true. I had a Quad Eight console at first that sounded really good. I always really liked it, but my holy grail was always to try to find a Spectra. It seemed like all the records I really loved the sound of were either done on a Spectra, or done with modified Spectra electronics.

Where did that Spectra Sonics console come from?

From this guy who used to live on an island off of Washington. He has a bunch of Stephens Electronics [Tape Op #54] machines and gear like that. He had this Spectra that was originally installed in L.A. in '70 or something like that. I bought it from him.

Did you get another one for parts?

I got a whole other one that I let my friends use at The Diamond Mine in Queens. Do you know those guys? Homer Steinweiss and Leon Michels. They've got my other Spectra, and they use it all the time.

It's nice to see it working.

Yeah, totally. Theirs is nicer than mine. I swear, I think it sounds better.

What is it about the Spectra Sonics that attracted you, besides the records you heard them on?

Well, you know Mark Neill told me all about them. He got me super hyped up on them. Then I was investigating and listening to records. The proof was in the pudding. I heard a bunch of records that I loved the sound of, and they were all Spectra. Then, on top of that, it was having Mark explain to me how they were set up and how to use them.

It's a different circuit design, in certain ways. The speed of the mic preamp was a little different than other gear that was being built in that era.

Yeah, it was pretty unique unto itself. I don't know. It's tough. It's got a bangin' low end, and it doesn't like to be distorted. The Quad Eight could get fuzzy, in a cool way; but that's not what the Spectra is for. It's for getting big euphonic sounds without super precision top end. It's got a softer, iron transformer sound; but still solid.

Have you tried any of the new Spectra Sonics outboards?

Yeah, it's great. It's all really good. Great circuits.

I got one of the old 610 Complimiters years ago.

Everybody loves those, once you figure out how to use them.

They distort great, but then you've got to figure out how to back them off.

Yeah, I had one, and I was like, "I don't really get it. The [Universal Audio] 1176 is way better." 1176 is the easiest thing to use. That's why it's the most common.

With recording equipment, if there's a learning curve, it's more likely that you're going to be averse to it because it can screw you up on a session.

And it's like a lot of guitar amps. When you start adding more knobs, the sound changes.

Like the early '80s. Guitars got shrill and nasty. Even amps got nasty sounding.

Yeah. The reverb sucked. Everything sucked. It's weird. Lots of guys in Nashville made millions and millions of dollars making hit records in the '80s, and I can't even listen to them. There's still a lot of those guys around too.

Careful!

No, I mean it's not their fault.

No. It was the time and place. Those records came out of every city, at that point.

It's such a bummer.There are a lot of musicians who I've never even given a chance to because they cut their records in the '80s. There're a lot of great country singers that I don't even really know about because I never even let my ears open up to them. All the guys I talk to all knew that it sounded like shit. They all tell me it sounded like shit. All of them. But what are you going to do? It's business.

Did you produce your dad's record? [Chuck Auerbach, Remember Me]

Yeah. He's always been into songwriting. He would write a lot of songs. He doesn't really play an instrument. But he got it in his head that he wanted to make a record. So he booked a studio, The Butcher Shoppe, across town. He booked a bunch of my musicians, and he did it on a day that he knew I was free.

He knew you'd come by.

So I went over and helped him make the record. It took a couple days. It was fun.

Did you charge him double?

I charged him triple! [laughter]

I love that. What was producing The Pretenders' record like [Alone]? Richard Swift [Tape Op #120] and I talked a little bit about that session.

Yeah, we did that here. Chrissie [Hynde] is from Akron, just like me. I don't know what it is about Akron people, but we've got this similar tone. We instantly got along. She came here, and it was like any of these albums. She let me choose the band. I had Richard come in, and some of my other buddies. We cut a record quickly. She'd written a bunch of songs, and we cut them live. We had the headphones on, and we started playing. Then she started singing, and it's her voice. It's like, "Whoa, holy shit! That's that voice!"

It must be a trip to hear a voice like Chrissie's, or to hear Dr. John, in the middle of tracking.

Well, yeah. It changes you when you get a chance to work with a musician who can transcend space and time, and well as mutate inanimate objects, like a piano, into this living, breathing thing. You don't want to change. That's what I want to strive for; working with people like that all the time. I want all of my sessions to feel like that. I know they can't, but I want them to.

When you get a chance to produce Chrissie Hynde or Dr. John [Locked Down], does it feel like you're getting to cast them in a light where they're making a record that you've always wanted to hear, in a way?

Maybe not the record that I always wanted them to do. But I put them in a situation where I think it's going to be great. You know, where I'm excited to hear what's gonna happen. Do you know what I mean? It's hard to explain. It's different for every person. But with Dr. John, you know, he's such a New Orleans person. The drummer, Max [Weissenfeldt] from Germany, is an Afrobeat wiz. I knew it would be a great combination. With Nick Movshon on bass, I knew that would be great for Max. It was awesome. He took right to it; he loved it. He was a little skeptical going into the studio.

Yeah, but at that point Dr. John's made how many records?

Totally. That's a lot of [Yamaha] DX7 strings. And I'm sure he's been screwed by almost every label, at some point or another. So, yeah; he had reason to be skeptical. But it was fun. We had a great time.

It sounds great. What's in the future for you, session-wise?

We're booked all the time. Working on records, putting them out. We put out the [Shannon & The] Clams album [Onion], and the Robert Finley [Goin' Platinum]. We recorded a country singer, a young kid from Slapout, Alabama, named Dee White. So that's coming up. We've got a bunch of other albums. We did some reissues of some Link Wray, with never heard before tracks and never seen photographs.We've got another Link Wray 45 coming out. Then I got my hands on some old catalogs that I'm also going to be releasing. I can't say anything right now, but I'm looking forward to that.

When you're working with other artists, in what ways does that also influence you when you come back to doing The Black Keys, or to your solo work?

I don't know. I haven't made a Black Keys record since doing all that. Time will tell. But I come in here every day, and I feel like anything can happen. I don't put any rule on what's gonna happen. You see where it takes you. With each artist that I work with, anything's possible. I guess that's the fun of it.

Is there any artist out there that you're dying to record but haven't reached out to yet? What would be your dream production job?

I've worked with a bunch of people I love. I've got a few lined up.

I was listening to Sonny Smith's [Rod For Your Love]. How was that to make?

That record was so fun. I picked up Sonny and his band at the Greyhound station in the morning. I brought them over to the house and let them wash the sludge off themselves. Then we started the record. We cut it in a few days.

They really took a Greyhound out here?

They did. He's such a great songwriter. He writes catchy songs; you know?

With something like that, are you doing pre-production or is that happening on the floor?

That was on the floor. For Shannon's, we wrote them all ahead of time, and she wrote some of them herself. But with Sonny, he had the songs, and we went into it.

In a case like that, will you be out there and think, "Oh, what about this part?" Or will you pick who elevates what section, and who drops out?

Exactly. Sometimes it's easier to hear from the control room. A lot of times I'll be in the headphones, and I won't see the big picture. Sometimes I've got to get in the control room and listen to the big speakers before I feel like I can really wrap my mind around things. A lot of times I feel like I'm there to help musicians hear what they would hear anyways. Just help them along.

Do you find yourself working with changing tempos a lot when producing?

Yeah. You know, I mentioned my friend Billy Sanford. He played on all the Johnny Paycheck hits, but there's one in particular, "Someone To Give My Love To." The chorus is like 120 bpm, and the verses are 112 bpm. It jumps back and forth. He wrote it all out one time for me; all the bpm changes. They'd talked about them ahead of time. After working with people like that, and then going back and listening to some of these old records again, I started hearing things that I didn't hear before. I started understanding the depth of how tight those guys were; how musical it was.

They had room to be able to play like that.

To express themselves. They were artists. I did some work with Bobby Bare, and he said that the thing that helped him have some of the most success was trusting the song. He didn't try to sing crazy melodies around the melody. He just sang the melody. You know what I mean? He put his trust in the song, and put his trust in the musicians. The more I work with people like that, the more I understand.

As of publishing, Richard Swift has passed away. Honor him by listening to the great work he left behind.