Daniel Lanois' career reads like an enviable work of fantasy. From his early projects with Brian Eno and Harold Budd on their genre defining "ambient" recordings, to a pivotal role on U2 classics like The Unforgettable Fire, The Joshua Tree, and Achtung Baby, to his work with Bob Dylan, Emmylou Harris, Willie Nelson, Aaron Neville, as well as his body of work as a band leader and solo artist, Daniel Lanois has continued to look forward – and stay inspired – by being at once a master and student of his craft. His latest release, Daniel Lanois x Venetian Snares (a collaboration with Canadian electronic musician Aaron Funk), keeps the tradition of not just pushing, but ignoring boundaries. Online publisher Geoff Stanfield caught up with Daniel to discuss this latest release and what's happened since we last interviewed Daniel back in Tape Op #37.

You have a new record with Venetian Snares. I was curious how that collaboration came together.

A mutual friend introduced me to Venetian Snares' music about 7 or 8 years ago. I thought he was a master at his craft. He did a show in Toronto about two years back, and I went to hear him. It sounded really great. We met afterwards; there was a bit of a hang at my studio in Toronto and we started jamming. Out of one jam came a lot of material, so I said, "Why don't we keep going here and see if we have a record?" It was that simple. Not a lot of words were spoken – we just started playing together. Much of what you hear is based on jams and ad-libs that emphasize the more thematic moments. That's the basis of the exchange.

How does Aaron help reframe what you do?

Well, I wouldn't have thought it was any kind of formula to operate by. His thing was so far out and so far away from what I do. But it seemed to be welcomed from Aaron to allow more of the gospel part of what I do to be part of the magic carpet ride here. I hope we managed to succeed in a few spots where two different forces came together – to be stronger than they would be in isolation.

Your past few records have been focused on the pedal steel, and they make me think of a utopia – they're very transportive. This collaboration is very contemporary and contextualized in a way that's current of the times, with all the madness in the world.

Well, you're not too far off. That's how I started looking at it, as Aaron was introducing these angular injections into the beauty of what I do. I have no choice, at a certain point, other than to just follow his conducting. It's jagged, exciting, and arresting. It's not anything you'd put on to have something in the background to do the dishes by. You definitely want to put on this record if you're looking to have something shaken up in you emotionally. It's the job of art, isn't it? I love Barry White's "Can't Get Enough of Your Love, Babe." It's great, and I welcome it, but this is like, "We've got a little bit too much of something here, and I'm ready to stop myself in my tracks." Maybe a couple other listeners agree with us. It's meant to be angular, and there's meant to be some bottled-up emotions, anger, and mistrust; just pushing the envelope to the point of where I imagine jazz players got to in the '50s when they splintered away from big band. They were angry young men, and it spawned the likes of Elvin Jones, John Coltrane, Miles Davis – people like that. They wanted to shatter the mold and take the music to another dimension – that was the responsibility they took on. I'm not suggesting we're Elvin Jones and Coltrane here; but we're driven by similar values, in the sense that we're looking for something beyond familiar prescription.

I get a lot of that from this record and your music. Especially on your Flesh and Machine album a few years ago. What are some of the differences between those two projects?

I see this as part of a trilogy. Working backwards, I made a nice record with Rocco DeLuca called Goodbye to Language on the steel guitar. Flesh and Machine was prior to that, and now Venetian Snares. I see this as a chapter of time. I've seen these before when I first went to New Orleans; we made a Dylan record and then a solo record of mine. They belong as a little grouping. I think what's sweet about groupings, is that you get a philosophical spillover from one to the other. As long as the one has its integrity intact, that's the kind of spilling you want to be operating by. I don't know that I'll make another record that's as steel guitar driven as this and Goodbye to Language, but I believe they belong together.

Can you talk a little bit about the physical setup?

Yes. Well, from the audience's perspective, if they can be looking at the two artists in profile, that's okay. You get to see what we're doing a little bit more. But, that aside, proximity has been a friend to me. The closer people are together as players, the better they play. We're just taking advantage of the fact that it's how we sit in the recording studio. Let's do the same thing live so we're not suddenly sitting in different directions and losing the communication power we built in the studio. It was Aaron's suggestion. He said, "Why don't we play sitting down, and take what we have in the studio and bring it to the stage?"

With something like breakcore, one of Aaron's genres, were you drawn to that because it was something that was so out of your wheelhouse?

Well, that's part of it. I realized that Aaron knew a lot that I didn't know much about. But the specifics of breakcore aside, that's a long time ago. We're trying to bring what it is of that that we appreciate and admire into this body of work. What I do like about breakcore, and what Aaron's up to in these times, is that there's high-fidelity in his sounds. There may be times when I get kind of murky on my steel guitar, because the steel guitar comes through an old Fender amp, so you're never going to get the kind of sparkle that tiny speakers in earbuds generate. I'm happy to be in the company of somebody who's taking care of the high-frequency details, and also that great hip-hop bottom. Those are my favorite colors in hip-hop and in reggae. No matter what speaker you hear Bob Marley on, there's always something sweet at the top. We are afforded that luxury on this record.

I was fortunate enough to spend some time with Lee "Scratch" Perry recently. I know dub music has been a pretty big influence of yours for a very long time, in terms of your approach to mixing, deconstructing mixes and sounds, and building them back up. Was that also part of the way that you made this record?

Well, I'm glad you brought up Lee "Scratch" Perry, because he's a hero to all of us for his innovation. I do dubs but, as you know, we talked about my technique. The "Scratch" dubs are a little further out, and based on the triplet echo tradition that we all love. My thing is that I extrapolate, manipulate, and stick [sounds] back in. It's not a very good live technique; it's something I do in the studio. I've sat with Lee "Scratch" Perry at a nighttime bar. I don't know if I could use the word proximity one more time, but by proximity I felt that the master had spoken; student Lanois gets to go off now and hopefully find his own voice. He's done so much – he can be as far out as he wants. The further out, the better. I don't want to know his technique; I just want to feel his spirit.

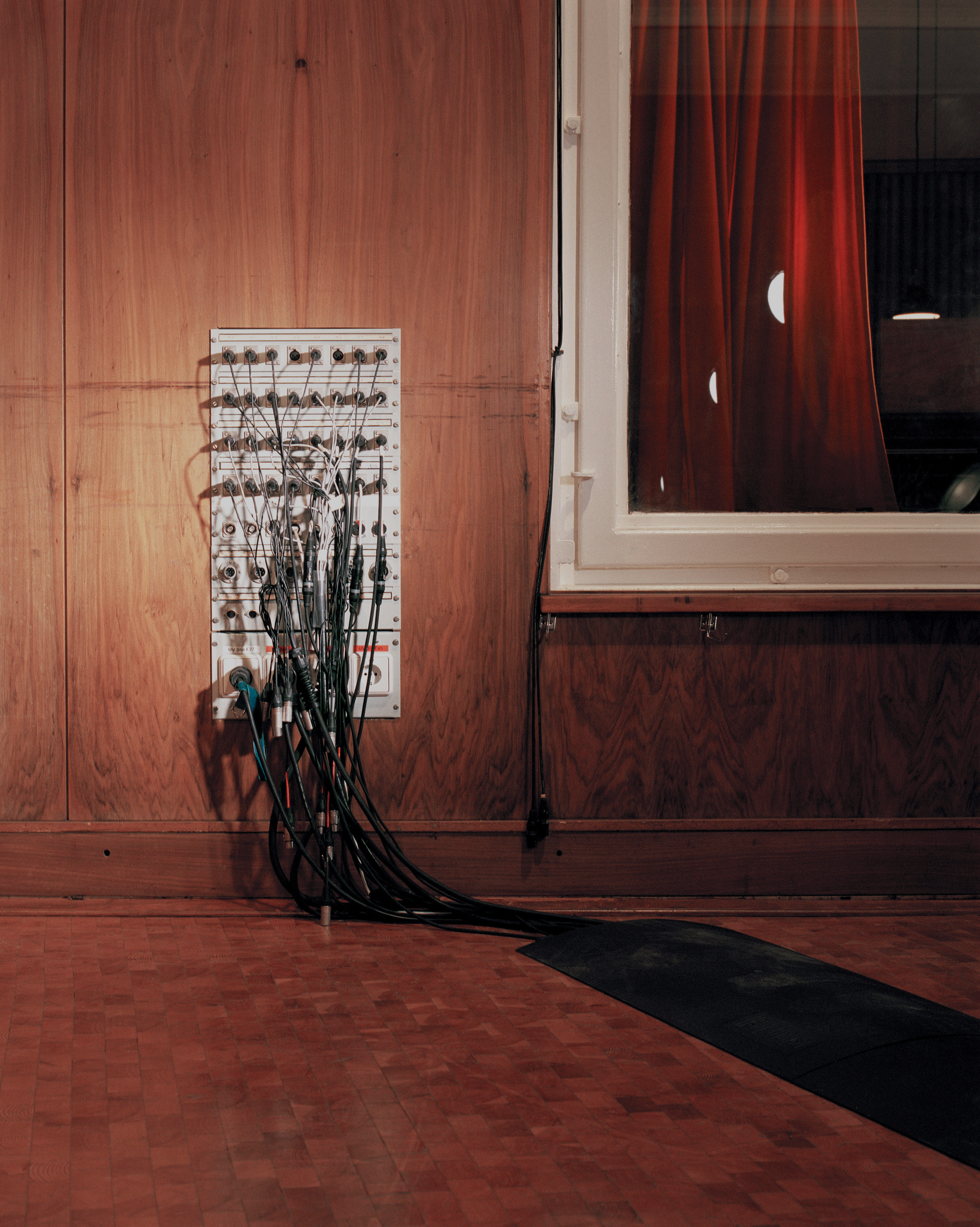

You've done a lot of records in sort of non-traditional spaces, and you did this one in a Buddhist temple that has been made into a studio. How does location add to the end result?

We try to pick fascinating locations. Music can be made in all kinds of places now, as we all know. You can make a record in the bathroom of an airplane with the right computer. Portable, battery-operated Ableton Live, and off you go. I wanted a shop in Toronto, because I didn't want a studio in my apartment anymore. This Buddhist temple came up. The monks were moving out, and I felt there was obviously a spirit in the walls. It's in an old Polish neighborhood of Toronto, with family-run businesses around the corner. We like the life and blood that has come before us here, certainly by the Polish and the monks. It's a nice neighborhood, and I feel I'm part of a community here. That goes a long way. It doesn't mean to say that we might not go to some hidden mountain in Tibet to make the next one, but this has served pretty well for now.

Are you based in Toronto now more permanently, or is this just a fresh environment after being in Silver Lake [Los Angeles] for so long?

I wish I could tell you that I was planted in any specific place, for any length of time. I try, but I keep moving. The Silver Lake studio had nothing to do with this record. We thought, "We're both Canadian. Maybe we'll do it in Canada this time around." I still love the Silver Lake studio, even though I'm hardly there. I was there a few weeks ago with a productive session – unrelated to Aaron Funk. I did a record with a couple of buddies; Brian Blade and Chris Thomas, the bassist who works for Brian. I wanted more of the Mississippi River sound, and those fellas grew up on the Mississippi. It was really my way of paying respect to how much I learned from America and the South. To this day I can't say enough about it, and I was lucky enough to provide a Grammy award to a couple of national treasures, including Bob Dylan. I feel like I've done my duty as a Canadian visitor. But hey, these are pretty interesting times. There's so much cross-pollination going on. It's a great time to be alive, and a great time to be doing music. I can carry an entire multitrack in a tiny drive now, and they don't bother me at customs the way I used to when I carried 2-inch tapes!

You've had this incredible career as a producer, and you've also been incredibly prolific as an artist and performer. How do you reconcile those two?

Back in the '80s the boxes were even more segregated. I was either producing a record or making one of my own. What's happened with recording equipment, and my life, is I'm living closer to the studio now, and it's all mixing together. I'm glad it happened the way it did. In these fast times, we can quickly switch hats. I'm enjoying collaboration, as was the case here with Venetian Snares. There was a time when I might have produced a record for someone like Aaron; but now I'm involved creatively, and we take it to the stage. I like that these times have taken me far away from being a wallflower. I can quickly set up a tour, we hit the stage, and bring our wares. I think it's keeping it real for me. I like the challenge of playing live, as well as the responsibility. We sound good live – his thing is so rock solid. The bigger the PA, the more magnificent he sounds. His line level is really, really punchy. It reminds me of some of the King Sunny Adé I'd seen as a kid, where it sounded like a cannon coming out of the PA. I've got to keep up with him. Plus he takes a feed off my steel guitar and starts sampling me and manipulating the sound right on stage. I've got no choice but to follow my new conductor. I hadn't felt that since when I was a kid in my first psychedelic band; that loss of control where the sound takes over and decides where you're going next.

It must be liberating for you when you're often otherwise tasked with being the boss in many situations.

Well, I'm pretty used to being the boss as the secretary/treasurer. Now I like this feeling of, "Muzzle me, send me to the stage, electrocute me, and then see what happens."

How do you stay inspired?

It's necessary to stay inspired. I've bumped into folks who made popular records back in the day, but stopped making records. "Why should we keep making records? Records don't sell, and nobody cares," and all this. It's probably true, except that's not a good sign of being inspired. How can you not be inspired by life, and by music for that matter? There might be a bunch of songs on the radio that make you angry, and make you want to create better music. That's a bizarre inspiration, but an inspiration nonetheless. Could I diplomatically say that I'm not chained by duty? My kid's grown up, and he's in his 30s. I don't have to change any diapers, or go to any class reunions, or crazy shit. All my other friends have, "Oh, I've got to take Rita to basketball lessons" or something. I'm a free spirit; I'm as single as I've ever been. I gave up a lot domestically, but my devotion to my craft and skills has never wavered. I like to think that I'm doing some of my best work, consequently.

How do you perceive limitations in music?

Limitations by skill are pretty obvious. Maybe you're excited by a certain approach and just getting good at something for a while. You might be excited about harmony and vocal arrangements, and that's what you do for a while. In regard to processing and effects in the studio, I usually have only three boxes going; whatever I'm excited about at any given time. Those old-school AMS [Neve] Harmonizers, the Lexicon Prime Time [delay], and then a more modern box, like an Eventide snazzy processor with 200 sounds. I do what I've always done. I feed one effect into the other, then back to the first, and then maybe into a third. By introducing unexpected modulations, I pick up a little bit of humanity along the way, such as more opera-like voices. As always, if I'm lucky enough to hit upon a sound I just described, I try and print it. I don't really use plug-ins, so it makes it harder to get back to things that might have a complicated chain of regeneration. Then I've got it and I can bring up those tracks as special effects in my mix.

It seems over the last decade you've focused on doing your own projects rather than being heavy in the producer world.

How would you look back on that chapter? Secondarily, how do you choose what to do next in terms of people approaching you?

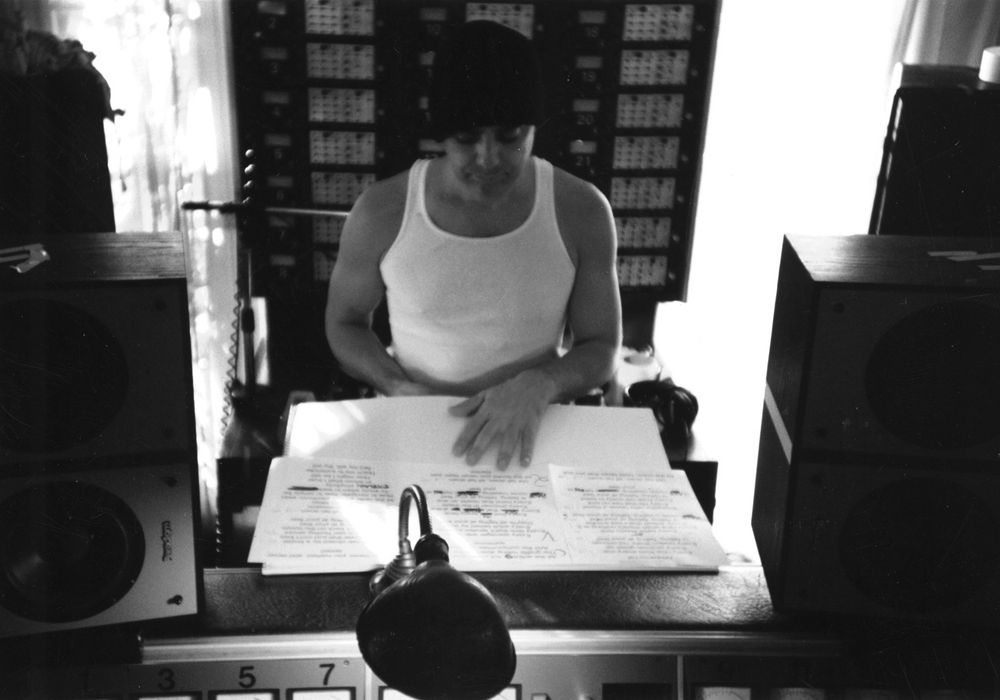

Well, looking back at records I made as a kid, there are so many. It brings me to tears the amount of time I've spent in the chair. I don't know that I could ever do that again; it was an absurdity of devotion. A lot of the records I made when I was a kid people don't know about. I've been involved with thousands of albums, and some of them were just one or two days in the studio per album, with gospel records and so on. I wasn't really in a geographical location where there was that much going on, so I just did more and more of the regular daily work. I was looking at it as a day job. I'm glad I made the records I made, with some pretty smart artists in the '80s and '90s, including Dylan. I don't know if I could be that person ever again. It belongs to a certain chapter of my life, or several chapters back then. But I love music more than ever. But I don't know that I could get in the hot seat for two years in a row ever again, unless it's a collaborative record. I see younger producers who have the same spirit I had as a kid, and I wish them the best. Super-smart people with new techniques. A lot of pop record makers. I've been meeting a few of those folks in L.A. these days. They don't want to touch anything if it's not going to be a hit. I don't know if I love the music all that much, but I admire that they take that position. Part of me wants to make a hit with Rihanna. I've got a couple of tracks; maybe I'll give her a call. I think she's a great singer.

You've mentioned several times over this conversation the word "gospel." You even mentioned that this new record allows you to access the gospel side of your playing. I was curious what your definition of that is, and what that means to you?

Well, I guess the term gospel has evolved considerably, at least in my mind. I play in a gospel band with Brian Blade in Shreveport, Louisiana, called The Hallelujah Train. Brian's father [Brady Blade, Sr.] is a great singing pastor. We're regrouping in September to do a couple of shows. I have my foot in the Zion Baptist Church music. That aside, it's a loosely-used term to suggest that the steel guitar takes me to that place of hymn or contemporary melody, that we might hear as an Appalachian melody or an all-Irish melody. That part of me that can go [sings], and those kind of guttural country melodies; they come from vagabond songs from people who travel, are questioning life, and are wondering what secrets the universe might hold. That part of us as artists who question – and questioning is necessary for evolution to even happen – lives on in me. It lives on in tradition, and it lives on in wanting more than just melodies from the past or traditional ways. I respect tradition, especially if it gives me access to the future. But the gospel thing is alive; I'm using it as a loose term for something that's grounded and has ancient emotion still tangled up in there somewhere.

_display_horizontal.jpg)