Musician and entrepreneur Jack White [Tape Op #82] has opened a brand-new storefront and vinyl record pressing plant in the historic Cass Corridor section of Detroit, a place that's been home to artists and musicians for decades and is now experiencing a renaissance. Third Man Pressing helps fulfill the increasing demand for vinyl records, plays a vital role in the resurgence of vinyl culture, and contributes to the rebirth of Detroit. White also founded Third Man Records, which has also released music by his bands, The White Stripes, Dead Weather, The Raconteurs, as well as his recent solo album (Boarding House Reach). White has produced countless records, released scores of records by many artists on Third Man Records, written a children's book (We're Going To Be Friends), and put out other authors' work on Third Man Books. He's also helped support music education for kids, acted in films, and created the unique Blue Room; the only live venue in the world where artists can record live-to-acetate. Detroit's Third Man Records and Third Man Pressing Plant feels like a small, family business. Workers earn a living wage of $15 an hour, with full benefits, and the company eschews traditional job titles. Instead, most everyone can jump in to help wherever work needs to get done. David Buick was kind enough to give me a tour of the pressing plant and tell me a bit about what goes on there, and Roe Peterhans, who runs the Detroit operation, chimed in during our conversation.

The Third Man Records store has been open in Detroit since when?

David Buick: We opened to the public on Black Friday of 2015, the day after Thanksgiving.

And the Third Man Pressing plant?

DB: The end of February 2017.

Can you talk about the history of the Cass Corridor neighborhood, and why you chose to put the store and the plant here?

DB: This is the center of the Cass Corridor, which was re-branded "Midtown Detroit" about ten years ago to try to fancify the neighborhood. But, since way back with blues and soul musicians, it's always been a hub of artists, musicians, poets, sculptors, painters, drug addicts, prostitutes, and bad guys. It was always the seedy, creative, free-thinking neighborhood. Gold Dollar was a venue where the White Stripes first played, which is not even a mile south of us. Zoot's Coffeehouse venue was a block away. The old Freezer Theater and the Clubhouse were nearby, and they were the main venues for the early ‘80s hardcore scene. There's The Old Miami; a bar that's been supporting the music scene for years. This is the hub of many different generations of music in Detroit. That's what the murals in the front of our store represent. There's a big MC5 mural, of them playing at the Wayne State [University] football field, which is right down the block. Then there's The White Stripes playing at the Gold Dollar. And then the next one is The Gories playing at an old art gallery, which was on the same block as us right now. When the opportunity came to get right here in the heart of it, Jack, of course, jumped on it.

How many manufacturing jobs will the pressing plant supply?

DB: What are they saying, Roe? How many jobs will there be when we go to three shifts?

Roe Peterhans: About 40 to 50.

DB: We're in the process of adding a full second shift. And then once that starts running smoothly, we're going to add a third shift. And at that point it'll be about 40 to 50 [manufacturing jobs]. And we have about 15 in the front of the house. It's a sizeable amount of jobs.

What are the different jobs, and what does each position entail?

DB: As a company, our theory is [to have] no job titles. If you look at my card, my job title on there is "Romantic Comedian." Jack feels if you give someone a title, that will limit what they'll do. But Randy is the person that oversees the whole plant, and then his right-hand man, Brandon, is like the foreman. There are people QC-ing [quality control], people that are running the presses, and people running the packaging and the shrink wrapper. But, for the most part, those rotate. There are some skills certain people feel more comfortable with, or are better at. But everyone can hop from job to job.

After you get up to three shifts, how many records can you manufacture in a day?

DB: We estimate, if all eight machines are running completely smoothly, about 5,000 a shift. So that would be 15,000 for a three-shift day, eventually.

I read that you bought new presses from Newbilt Machinery [a German company]. Are they all up and running?

DB: Yeah, all eight are up and running.

When did you get them working?

DB: We were test running and then pressing product for a month and a half before the opening. No one that started the plant – other than our customer service whiz, Jessica, who came up from United Record Pressing [Nashville] – had any experience in a pressing plant. Some people had experience working with other injection molds and other factories. Everybody was learning, because it's not just pressing buttons.

What were the first records you guys pressed here?

DB: Opening weekend we pressed the first two White Stripes records [The White Stripes, De Stijl], a deluxe version of the first Stooges record [The Stooges], and a reissue of the first MC5 record [Kick Out the Jams]. Those were all on Third Man Records; we licensed those last two, and of course we have The White Stripes. Our friends from ESP [Essential Screen Printing] set up in the back, and they were live silk-screening the covers for those. On another machine we had a gospel reissue project. We don't just do Third Man records here. We also had two 7-inch [presses] running, which was for Derrick May and Carl Craig. Those are two of the pioneers of the Detroit techno scene. Typically, their records are pressed on 12-inch [vinyl], so it was an exclusive thing.

What was the gospel record?

DB: The gospel record was by The Johnson Family Singers. Our friend, Mike McGonigal, is doing a Detroit gospel series – I believe he's pressed seven of them here. It's called the Detroit Gospel Reissue Project. Mike's a writer [Detroit Metro Times], and does magazines [Chemical Imbalance, YETI].

Is there a rough percentage of in-house Third Man Records pressings, versus other label's records?

DB: It's been random; whatever is in line. It's not always Third Man projects. We've been doing small, independent things, as well as a few major label runs. Third Man had a couple of really big projects, so there was about a week or two there where all the machines were Third Man, because we were doing The American Epic Sessions soundtrack albums for the PBS special.

What was that?

DB: "That was a four-part series on PBS that Jack co-produced with T Bone Burnett [Tape Op #67], Robert Redford, and a couple other fellows. Columbia Records, who put it out, did an actual soundtrack that was a compilation of the sessions that Jack White produced (including the Grammy Award-winning Alabama Shakes track). Third Man did a full companion soundtrack to it. There's also a soundtrack that Sony [Records] put out in partnership with us that's available all over as well. Our presses were bogged down with these for a couple weeks. The last episode was all modern-day musicians recording in the same style as these early sessions were recorded. The lathe is actually powered by a weight, and when the weight hits the ground it stops spinning and cutting. You have one single ribbon mic in a room. That's what the last episode is. There's also a record of that, but we didn't press that here. We pressed it down in Nashville. We work with United Record Pressing down in Nashville."

What is the Vault?

DB: It's a subscription/membership. We announce one, what the current Vault package is going to be, and then people have a certain amount of time to sign up for that one. Or you can have a year or lifetime subscription to it. It's for the diehards and collectors. They always get a couple live or unreleased demos, or a 7-inch. It's always different. Fancy, nice, deluxe packaging. They don't go back in print. They're only available in the Vault packages.

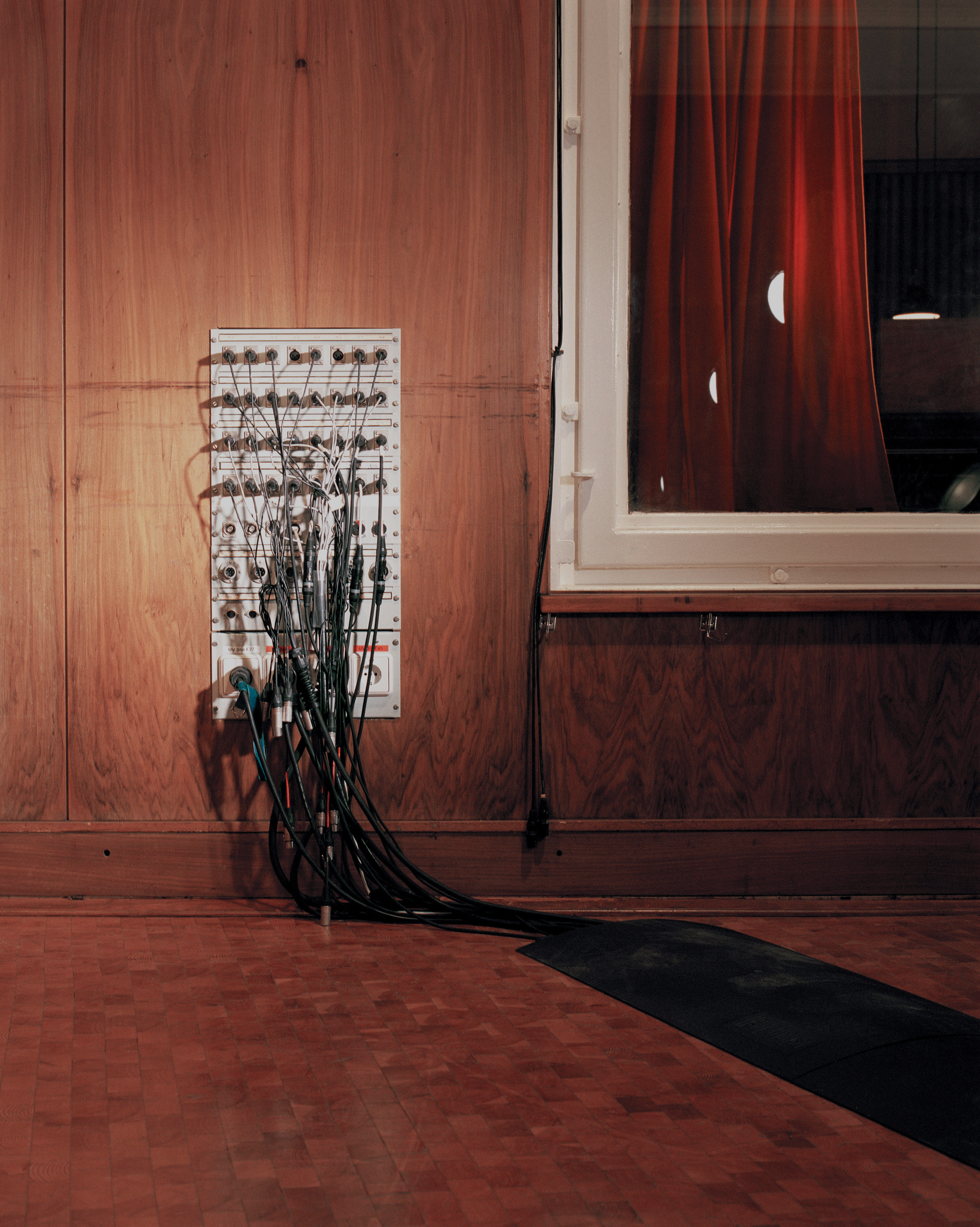

I wanted to ask about the live recording to acetate that you can do in Nashville. Can you only do that in Nashville?

DB: We're in the process of getting that set up here. We've been getting our studio in order. But yeah, we have a lathe, so we'll be able to do that here. There's a lathe in Nashville and you can record direct to acetate, and direct to tape sometimes. We have a whole series of live 12-inch LPs with Mudhoney, The Melvins, Willie Nelson, Jerry Lee Lewis, and a lot of crazy, different people. The engineers get the levels right, and the band will record one song just to make sure everything's cutting correctly. They pause, and then a light goes on that says "Cutting" and the band plays. They play for about 20 to 25 minutes, take a quick pause while we put on a new lacquer for Side B, and then play for another 20 to 25 minutes. All those records out there, they're not all flawless. There're some flubs here and there, but it's totally 100 percent live and mixed on the spot. It's a fun thing people are encouraged to clap, applaud, and yell.

And who are the engineers?

DB: Joshua V. Smith and Vance Powell [Tape Op #82] are down there in Nashville. George Ingram cuts the lacquer in Nashville; he's been doing it for years. For our Detroit team, we're still hashing that out.

If it's live to tape, do you make masters and then press records from those? Is that the process when you cut live to acetate? Do you use the acetate as a master to press records?

DB: No matter what, if we're doing it live, if someone's bringing in a digital file, a tape, a CD, whatever, once it's all mastered and all the levels are right, it gets cut on the lathe. You cut an acetate or a lacquer – the lacquer is a coated aluminum disc – and you do one lacquer for each side of the record. You send that off to an electro-plating place; you get this nickel and silver–coated disc, you peel off the nickel and silver, and you get a reverse of the lacquer. Those go in the stamper in the presses, and they transfer the grooves to make a vinyl record with the grooves that match the lacquer. Most places don't record directly to lacquer; we eliminate several steps with that. One time we did the world's fastest record, where Jack White did a live-to-lacquer session down in Nashville, and Ben Blackwell – who's one of Third Man's co-founders – took the lacquers and raced them across town to United Record Pressing. United made the stampers, put them on a press, and pressed up records. He drove back with records in under an hour. We call that the world's fastest record. People who were at the show got to go home with a record of the show. If you go online at Third Man Records, you can find the whole story of the world's fastest record.

I read about some unusual work you've done in the grooves of the records.

DB: We've made them so you play them from the inside out, like on Jack's Lazaretto record. One of the sides plays inside out on that, and then one of the songs, depending on where you put the needle, there's a different intro to the song. There's two side-by-side grooves that eventually go into the same one. There are essentially two different songs. And then we've put grooves on the label. Those are the big ones we've done so far: playing from the inside out, and having multiple songs on the same side of a record. There have been a few people over the years who have done side-by-side tracks. Depending on where you put it, there would be a whole different song. But no one had ever done it where it's a different beginning that merges into the same song. And you can't tell; it's very smooth.

I noticed that you're making 180-gram vinyl. What are the different weights you can do?

DB: We offer 180 and 130. Nowadays, that's pretty standard.

What's the difference?

DB: It [180 grams] will be less likely to warp, as well as less vibration for the record when it's spinning.

Where do you think the demand for vinyl is coming from these days?

DB: I think it's just the overall experience. There was a long time where it was dying. Then, in the past ten years, it seems like people are more into real objects that you can hold. Because there's no argument that it's a more personal and intimate experience to take out and put on a vinyl record, rather than scrolling through something digital.

Is there any actual vinyl in vinyl records?

DB: We use PVC pellets, so that's polyvinyl chloride.

RP: I can show you the record "seeds," as we like to call them.

And you melt them down?

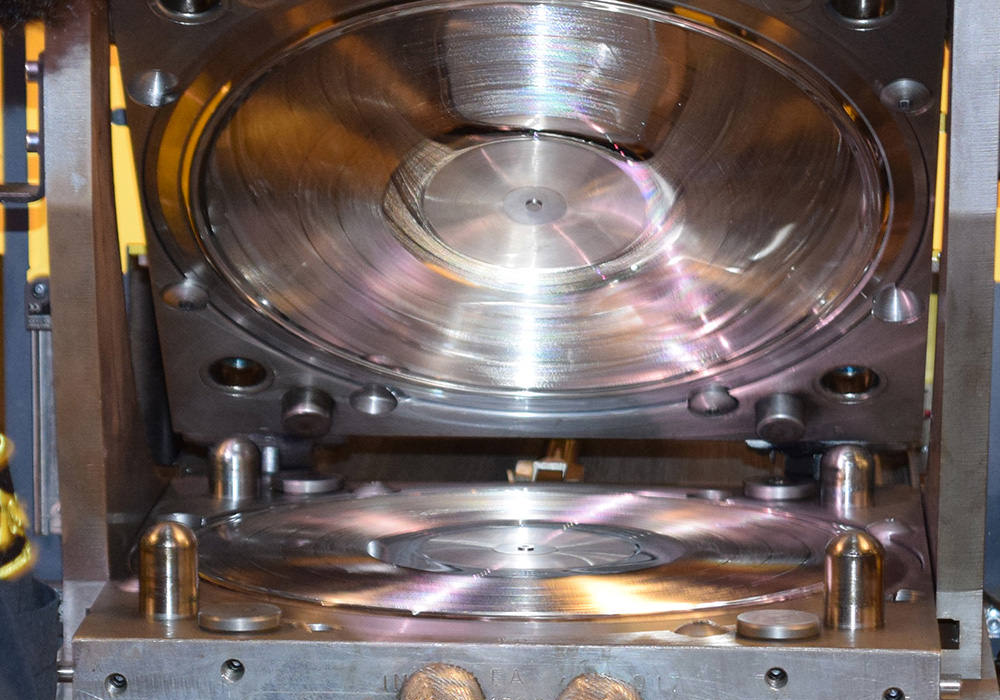

DB: Yeah; they're warmed up, and then a puck is formed, depending on what we're doing and what size. That gets put in the stamper, the presses. You press a button, the book mold closes, and it applies 3,000 pounds of pressure. Then steam heats them up, warms them up more, and then the vinyl spreads out and fills in the grooves.

[Roe comes over with a bag of pellets.]

RP: This is what it looks like. Black, or whatever color vinyl you're doing. That gets pulled through an extruder and squeezed like toothpaste. It comes out, and that creates an organic form, called a puck. We call it a puck, but biscuit is probably the most ubiquitous term in the industry. That then goes on the press and gets smashed into molds on the stampers.

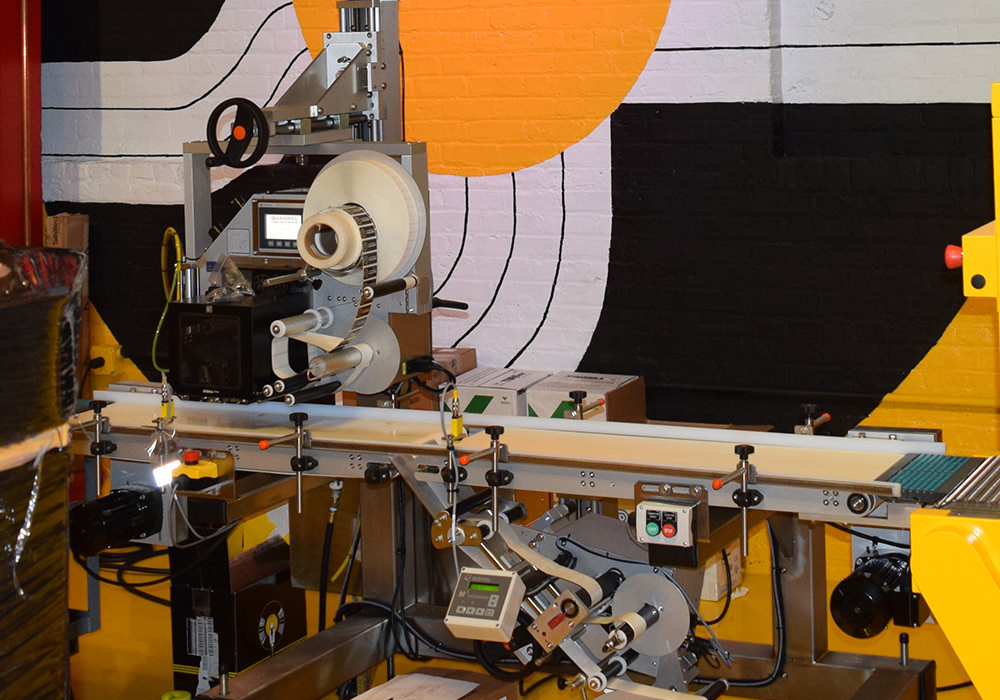

DB: And then, after a certain amount of time, cold water goes in and hardens the plastic. They come off; you trim off the excess PVC, and then they're ready to go.

What about Newbilt [Machinery] and the presses they make?

DB: Newbilt were servicing and making replacement parts for presses for a few decades. They're German-based. A few years ago, they noticed that no one was building new machines, and they thought they should start building new machines. They were the first company to start building new record presses in 35 or 40 years. We bought eight of the first ten that were made. The gentleman from Newbilt came over [from Germany] and spent a lot of time helping to set them up and helping us learn how to use them. They've come over here several times to be involved and make sure they're running smoothly. The thing that's nice about having new presses is that a few years ago, if a record plant had ten machines and one of them broke, it would be broken until you could track down the part or figure out how to manufacture a new one.

Like having an old tape machine.

DB: Absolutely. It's nice that we could stock up on some of the parts. And for others, if we need them, it's a matter of days to get them. In the past a machine could be down for months, or even years, until you tracked down the part for it. There's another company in Canada that's started making presses since Newbilt. Newbilt's are manual and the Canadian company's [machines] are automatic. But the machines themselves are basically the same idea as the ones from 40 years ago, just streamlined. The main difference between the old ones and our new ones is that the hydraulics, the chilled water, and the steam were all attached to the machines before. Now we're on a closed-loop system, so we have a chiller room, a hydraulics room, and a steam room. When you're in the actual plant, there's hardly any plant noise. There's no smell, and the temperature is very comfortable – it's very non-plant-like in there. And the machines look a lot smaller because all that isn't attached to them.

What about the comeback that's happened, and is happening, in Detroit in the past decade or two?

DB: There's a lot happening. It's very evident in the past five years or so. I've lived in the same house about a mile away from here for 22 years now. There's always been people opening stores and restaurants. The majority of them in the past didn't really stay; they struggled because a lot of the people that were visiting the city would come down for work and then go back out to the suburbs. In the past the word got out that you could buy a house for a dollar. That wasn't ever truly the case, even though a few people got lucky. But, it's a very easy and affordable city to live in for your artist-type people that don't really have a giant income. You could live comfortably, as well as have time and space to do whatever it is that you were doing. More and more people started coming, and independent businesses started opening, surviving, and thriving. This neighborhood, especially since we came in a couple of years ago, is really taking off. You come up to this neighborhood and there are families cruising around with their kids, people walking their dogs, and people coming down to shop. Five years ago, this neighborhood was abandoned.