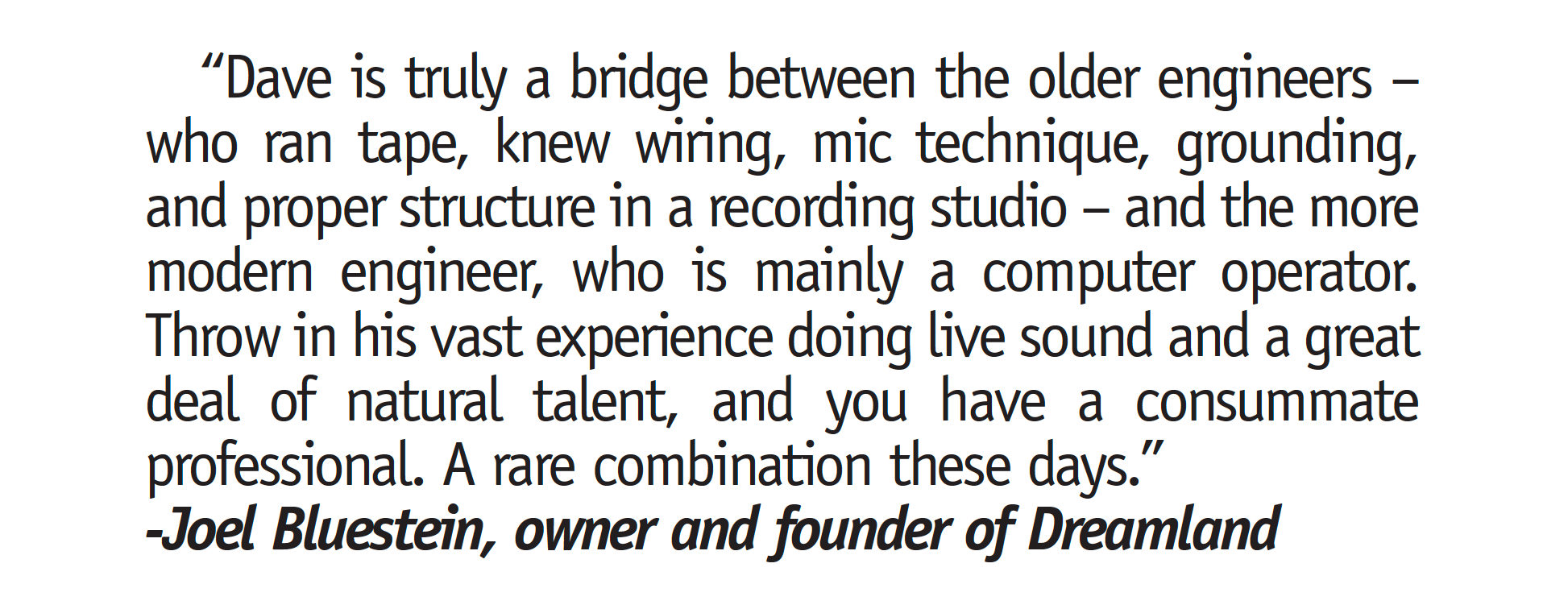

Dave Cook, recording and live engineer extraordinaire, has worked with The B-52s, King Crimson, Cindy Cashdollar, David Bowie, Amy Helm, Ravi Shankar, Mamadou Kelly, Maya Beiser, Suzanne Vega, and many other artists in many genres of music. He inspires confidence and ingenuity with all who have worked with him, from the famous Dreamland Recording Studios near Woodstock, New York, in a converted church, to his own Area 52 Studios in the Hudson Valley, to life on the road all over the world. How did this humble man behind the boards move from the big drum sound of '80s new wave to becoming the go-to guy for desert blues from Mali?

How did you first come to work at Dreamland?

I moved up river from New York in 1985. I heard that a new studio was being built in a church in West Hurley. I called the owner, Joel Bluestein. He explained to me that he had bought the building, and he had a crew who was supposed to be building the studio but that crew abandoned the project, leaving him stranded. At the time, I had some tech experience, as far as wiring, patchbays, and putting racks together. He hired me as a chief engineer right off the bat. I remember the day when we fired up the console. It was a mid-'70s API with a little 36 input by 24 monitor section, which was dubbed "The Jukebox." Very classic console. We fired that up, started troubleshooting for a couple of days, had a few test sessions, and we were up and running. That was the beginning of my time with Dreamland. The first session that we did there was great. During that period, my engineering friends in New York and I were listening to Peter Gabriel's Security record, trying to figure out how they did it. Jerry Marotta [Tape Op #33, drums] was on it, Larry Fast [#33] was on keys, and David Rhodes was on guitar. All these great guys. I was in the studio one day by myself, and the phone rang. It was Tony Levin [#33], Peter Gabriel's bass player. He's one of the world's best; having played with King Crimson, Paul Simon, and Stick Men. I had heard he was living up here, but I hadn't met him up to that point. He said, "Hi, this is Tony Levin. I'd like to come over and see the studio." He came over and checked it out. It was for a project that he was producing – a woman from out west – and they were gonna do a handful of songs. He said, "The band I'll be bringing in, it's gonna be me, Jerry Marotta, Larry Fast, and Sid McGinnis." He was playing guitar then, not David Rhodes. But essentially Security's rhythm section. I was an assistant engineer on this one, but the fact that I was in the room with these guys and seeing how they did their thing was pretty stellar.

You wouldn't necessarily think that a church is the best space to have a recording studio.

Actually, most were built to have the pastor or the priest stand there and speak to the whole congregation acoustically.

Is that a good thing?

Well, this was the '80s, so it was all about big. The big drum sound, the big snare sound in particular. It was the days of Bruce Springsteen's "Born in the U.S.A." – one of the loudest snare drums on record. The bigger the drum sound, the better. Everyone wanted to come to Dreamland and record drums. The main church room wasn't very insulated, so climate-wise it was very tough to deal with. It wasn't sound isolated either, so there were trucks and things that would go by that were tricky to deal with at the time. We'd put four or eight room mics around the place, trying to figure out the best spots for them, then we'd compress the crap out of those and make them as big as we could. The main draw of that studio was the big church space and its acoustics. Probably the biggest record to come out of there at that time was The B-52's record Cosmic Thing. At the beginning of "Love Shack" you really hear the sound of the church; those room mics were used a lot in that mix. For years I would get questions about how we got that drum sound. Don Was [Tape Op #113] produced four tracks on that record and Nile Rodgers did the rest. I don't know how Don found out about the studio, but the buzz was going around about the place. Two of The B-52s, Keith [Strickland] and Kate [Pierson], lived in the area and they wanted to stay local. It wasn't a big budget record; it was a comeback thing. They weren't bringing in an outside engineer either; they just needed to use someone good who knew the studio. I sent Don a cassette of some work that I had done. He loved it and said, "Yeah, great. Let's do the record." I was hired to do three weeks of tracking with them. "Love Shack" was the last track we did out of the four. At the time I felt it was almost a throwaway; an afterthought. Charlie Drayton, the drummer, wanted to experiment and he took down the standard drum set. Dreamland had this collection of ridiculously cool marching drums and African [percussion]. He collected a bunch and set up a drum set out of these drums, which sounded a little bizarre. We continued to get some sounds on it, then Don came back from a break and listened to him play the groove. He's like, "No, that's all wrong. We need to go back to standard drums." We went back to that and started doing the tune. Everyone in the control room, once the lyrics started happening, knew that this was something special. It was loads of fun to track. In the end, of course, it was the most successful tune on the record. In the middle of it, there's a stop, and Cindy [Wilson] yells out, "Tin roof rusted," which is a signpost for the whole tune. By today's standards it would be a miracle to be able to spend that much time. It was a much more relaxed schedule back then. You took tea breaks, you swam... There was a pool at Dreamland. A lot of stars swam in that pool. Bobby McFerrin swam naked in that pool. Yo-Yo Ma might've jumped in as well, but I can't confirm that! Nick Cave certainly swam there. That's something that a lot of us who came from that era miss... that laid-back attitude. It was more creative. You got to sit back and listen to things a little bit and really take it in. Instead of just, "Get it done. Get it done. We'll fix it later." A bit of the magic is gone. That being said, I say to people all the time that the way the technology works now, that you can send 192 tracks down [an ADAT] Lightpipe, for example, is insane. That's the new magic, but it's a different type of magic. It's technical magic. It isn't creative and mystical magic.

What were some other Dreamland examples of this old-school creativity.

How about Suzanne Vega's record, 99.9F°? The engineer on that was Tchad Blake [Tape Op #16]. He was one of the most innovative engineers that I've ever met. He was doing things with particular pieces of gear and mic'ing techniques that I had never seen before. He had just come from India and a lot of the street musicians and singers were using these PA systems by Ahuja. It's basically a big plastic horn with a power amp. He loved the sound of it. He bought one of these Ahuja's, and he started experimenting with running Suzanne's vocals through the Ahuja, which has this narrow 3 to 4 kHz bandwidth. He'd be mic'ing it from a distance in the church, and then running that back into the track as a vocal effect. You'll hear this vocal all over the album.

What did you do after you left Dreamland?

I ended up being hired as a chief engineer for an ashram.

Why does an ashram need a chief engineer?

Well, because they had an amazing studio. There was a heavy focus on music, on chanting. The ashram introduced me to Pro Tools.

That ashram was a high-tech place!

We didn't have a choice. We had to move forward. I started veering away from the ashram gig back in the early 2000s. I got into touring as a front of house guy. Over at Bard College, the Richard B. Fisher Center [for the Performing Arts] was opening up and they started hiring me to do shows that would come through. I did Elvis Costello with the Mingus Big Band, which was a one-off and a great show.

How did you come to open your own studio?

My studio, Area 52, came about eight years ago. I never really owned tons of gear, but I started to acquire some casual recording gear and some racks of live sound equipment that were in my house. I needed a place to keep it. This complex we're in, Markertek, had this room available. It's about 15 by 30; a small room. I was gonna use it as a storage space and an office outside of my house, just to clear out clutter. The room itself was an open space with a poured gray concrete floor. The owner of the building saw that we were doing music in here, got very interested in that, and was excited about the prospect of something musically happening on campus here. We started talking about the possibility of an actual tracking room. I pictured it as a small vocal booth, just to do some overdubs in. He said, "Okay, let's do it." He helped out with the construction considerably. On the other side of the wall was an open warehouse space, so we built out into that space and created the main room, put the glass in, put a floor in what is now the control room, put this wall in, and painted it. It was pretty bare bones in the beginning. Again, I didn't have a whole lot of gear. Very quickly, people started wanting to come and do projects here. The minimal gear at the time didn't seem to matter. They were coming to work with me, trusting I had what I needed for their project.

How did this studio become the North American center for African desert blues recording?

A very cool guy named Chris Nolan, of Clermont Music, lives not far away. He was involved in the Festival au Désert [Festival in the Desert] in Timbuktu [Mali]. He came back with some recordings from that concert about five or six years ago; just on a little handheld thing. Some were actual field recordings, made in a tent somewhere, but the majority of them were feeds from the console. He needed someone to edit, master, and figure out what to do with these, because he wanted to release a compilation record. Almost all of them were in really bad shape, with distorted feeds from the console or just bad mixes to begin with. We spent weeks filtering, compressing, EQ'ing, and restoring. We also went through hundreds of recordings, editing the recordings that he was deciding to use, and then doing whatever I could. Over the course of that, I was learning that Chris also managed a few other artists from Mali, like Khaira Arby, Mamadou Kelly, Oumar Konaté, and Leila Gobi. He'd do a North American tour with one or two of the acts simultaneously. He had it in his head, "Let's start doing some of the recordings here, and get some fresh American-cut tracks." Khaira Arby was the first artist that he brought in. We did her record and a few days, and after that we did Oumar Konaté, who was her young guitar player. It's been going ever since. Chris counted recently how many releases we've done from here, and I think it was 22.

How do these musicians like it here?

They go into the room, they play their music, and it's great. If we're looking to do something that's a little more appealing to the Western ear – where it's more produced, rock-solid time, very consistent, and perfectly in tune – we've gotta coax them along a little bit. Sometimes they play with click tracks, even though they're not used to that. That's a bit of a challenge, because they usually just go in there and play. They listen to a take, and they're like, "Okay, great. Move on." The musicians are all Muslims. Some of them are very devout, so there's no alcohol. They all speak French, and Chris is fluent in French, so he's an interpreter as well. They're very interesting sessions. With some of the artists – two or three times now – we've incorporated some of the local players here. Guitarist Cindy Cashdollar is on a couple. Violinist Iva Bittová was on one of them with Mamadou Kelly. Drummer Susie Ibarra as well. Excellent players. We've had ten to twelve people in these two rooms here. It's a circus, but it's loads of fun. The place gets trashed!

You said adding the click track takes it to another level. Why?

They will traditionally start in one tempo, and end in about double the tempo. It's what the music is. In a live setting, of course, with the audience throwing their hands over their heads dancing, that's what happens. They'll build the excitement, and the tempo will build. That's what they do. It makes editing a challenge.

In general, do you find music more or less click-tracked today than when you started?

It really varies. For the projects that need it, whether it's for overdubbing or building tracks, it's just a matter of course. People understand it, and they use it. But yeah, it really just depends. I did most of Amy Helm's solo record, Didn't It Rain. I don't think there was a click on that entire record. Very organic, roots, Americana-type music. It feels great. She's keeping it going. Her father, Levon Helm, played on a few tracks on that record; the last recordings he ever made. I came in about midway through the process. Everything was recorded at Levon's barn [Levon Helm Studios]. I mixed about half the record here. I think it's an excellent record.

How do you feel when musicians come in and try to tell you what equipment to use?

I got a request to do a clarinet and guitar duo record. I was way into it. The guitar player uses Royer microphones live. Pretty quickly he started asking me what kind of microphones I have and what we were gonna use, which is fine. As I mentioned earlier, I don't usually even have to answer those questions. People book me, knowing, "Dave's gonna have what we need. I don't care what it is." So, I'd finished a classical guitar record recently. On that we ended up using an AKG C414, and a couple of [Neumann] KM 184s, which is what I told him. His immediate response was, "The 184s don't work. Too bright for me." I was a little taken aback by it, but it was fine. He said, "I'm gonna have some Royers sent." John Jennings from Royer sent an SF24 stereo ribbon to use on the session. I have since fallen in love with that mic. This incident taught me to take in a little bit more when someone wants to suggest using some new equipment that I don't have.

Even after years of experience, you still can take some unsolicited advice?

Being in my own environment, with my own gear for so long, I find that I can stagnate. I'm doing things my way, and with my gear. When I'm in other places I can pick up tips and techniques that I wouldn't necessarily learn. Just go with it, and you'll learn a little bit.