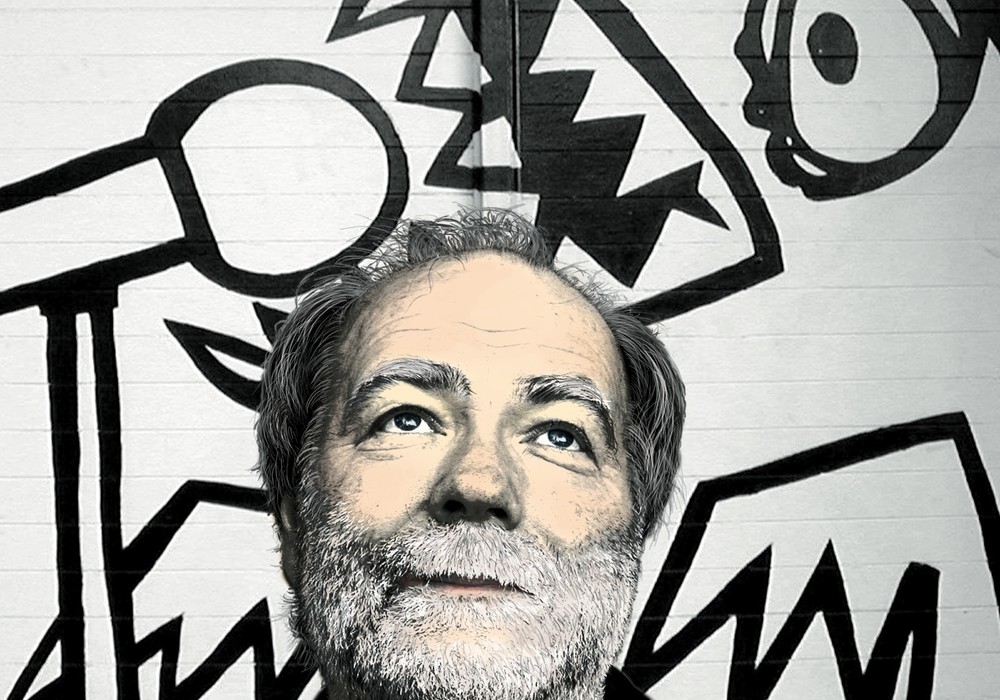

When I visited Nashville and interviewed Vance Powell [Tape Op #82] years ago, I met his buddy, Mitch Dane, who shared the Sputnik Sound studio space with him. Over the years Mitch and I have spent many hours hanging out, and his calm, focused demeanor and wise thoughts always inspired me. I figured it was time to chat with this amazing, Grammy award-winning producer and find out more about my friend.

You had an accident when you were young that affected your throat, and you couldn't talk for two years?

Yeah, that's right. In general, I think people take talking for granted and forget the importance of silence for so many facets of their growth and life. Whether you call it a blessing or a curse, it was given to me. I learned how to listen to the way things sound and how sounds are put together, but also how to listen to people and what they're actually saying.

You were a teenager then, right?

Yeah. I remember my friends would take me to game rooms, put quarters in the jukebox, and play pool. I couldn't talk, but I'd listen and play. It was fun for me, even though I couldn't speak.

How were you interacting socially at that time, as far as communication?

Well, I didn't have a lot to say. When you break it down, you only have to say, "I'm hungry," and "I have to go to the bathroom." I learned to not have an opinion about where we'd eat or where we'd go.

So much of what we have to do in the studio is to listen to music and to what others are saying.

Even now, I have to force myself to keep my mouth shut. It's a challenge.

Amazingly, after many operations, you got your voice back. You started doing music and playing as a songwriter and a singer, with a voice that's limited. What were the circumstances?

It was a weird situation. My doctor publicly said that it was a miracle that I could talk, so I started getting these calls from churches saying, "We heard that God did a miracle in your life. Can you come tell us about it?" They would ask if I'd sing a song, and it developed into a career of playing. I performed at a lot of colleges, high schools, and youth camps. Through the process of doing that, >I made my own records and sold them. I didn't know much about the industry. I ended up recording to MIDI, printing that to a DAT [digital audio tape], and then going into the studio and recording my vocals and guitar on top of it. I made my own tracks and sang on top of them. I had an [Akai] MPC60 that I used quite a bit; I loved the old soul and "Motown" drum loops. I incorporated those with my acoustic guitar. Eventually I put in a little studio booth and had a place in my garage that I worked out of.

Did other people start seeking you out to record with?

Yeah. After a show, people would come up and ask how I got started. Occasionally they'd ask me to help them do a record. I didn't take long to realize that it's really where I enjoyed the music; in the making of it. Less of the performance, and more, "Let's figure out how to make this song better and get it down on tape."

What was your later studio like?

I had ADATs and a 32-channel Mackie board. I often threatened that if I had that console and 12 [Shure SM]57s I could make a record.

You slowly taught yourself how to engineer?

To call myself an engineer is a stretch. I can get good sounds, but there are so many great engineers in this town who know why the gear works, not just how the gear works. I don't claim to be that at all. For producing, I come from more of a musical background. I have a knack for melody and arrangement. I've grown into my engineer ears as I continue to grow into the production part. I'm always learning something.

One of the projects you were known for early on was Jars of Clay. How did you first meet those guys?

I didn't actually meet them until I moved to Nashville. I believe one of them went to one of those youth camps that I was playing at, saw me, and bought one of my records. Later, in Nashville, we were at the same church and started having lunch together. We hit it...