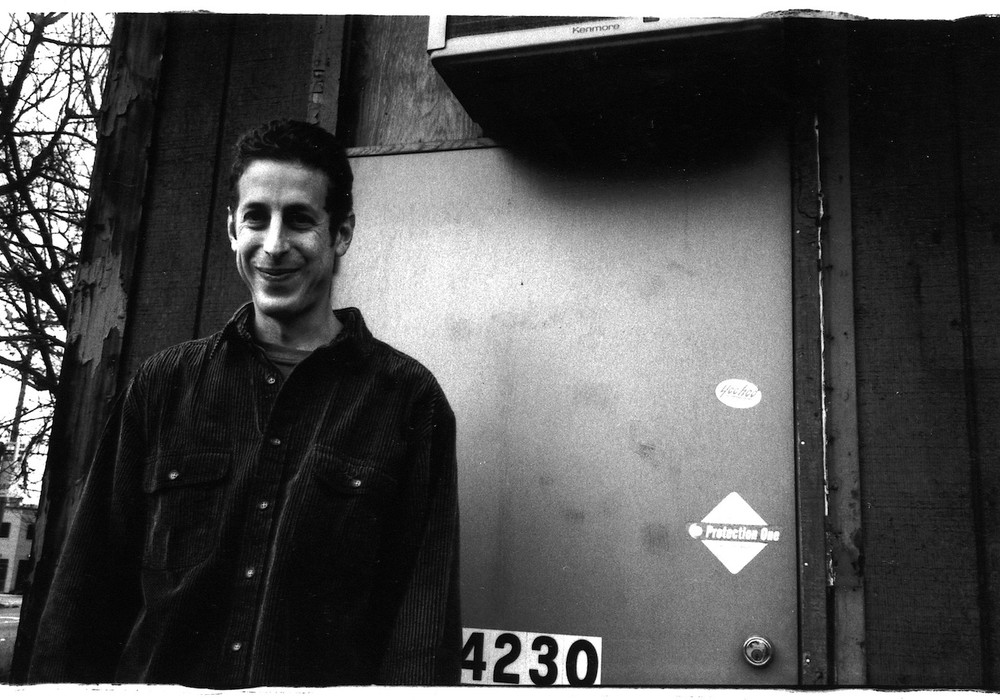

Andrew Sarlo's sense of being grounded, coupled with his simultaneous respect for personality and human emotion made for a unique and rewarding interview experience. Even with credits like Nick Hakim, Bon Iver, and Big Thief under his belt, as well as an already-established path into L.A.'s world of professional production, the 28-year old claims he's, "Still a baby, and I'm growing." Taking time away from a new project, Andrew chatted with me about what it was like learning under the masters at Berklee College of Music, the emotional response that music is capable of, and what that should mean to producers.

Where are you based these days?

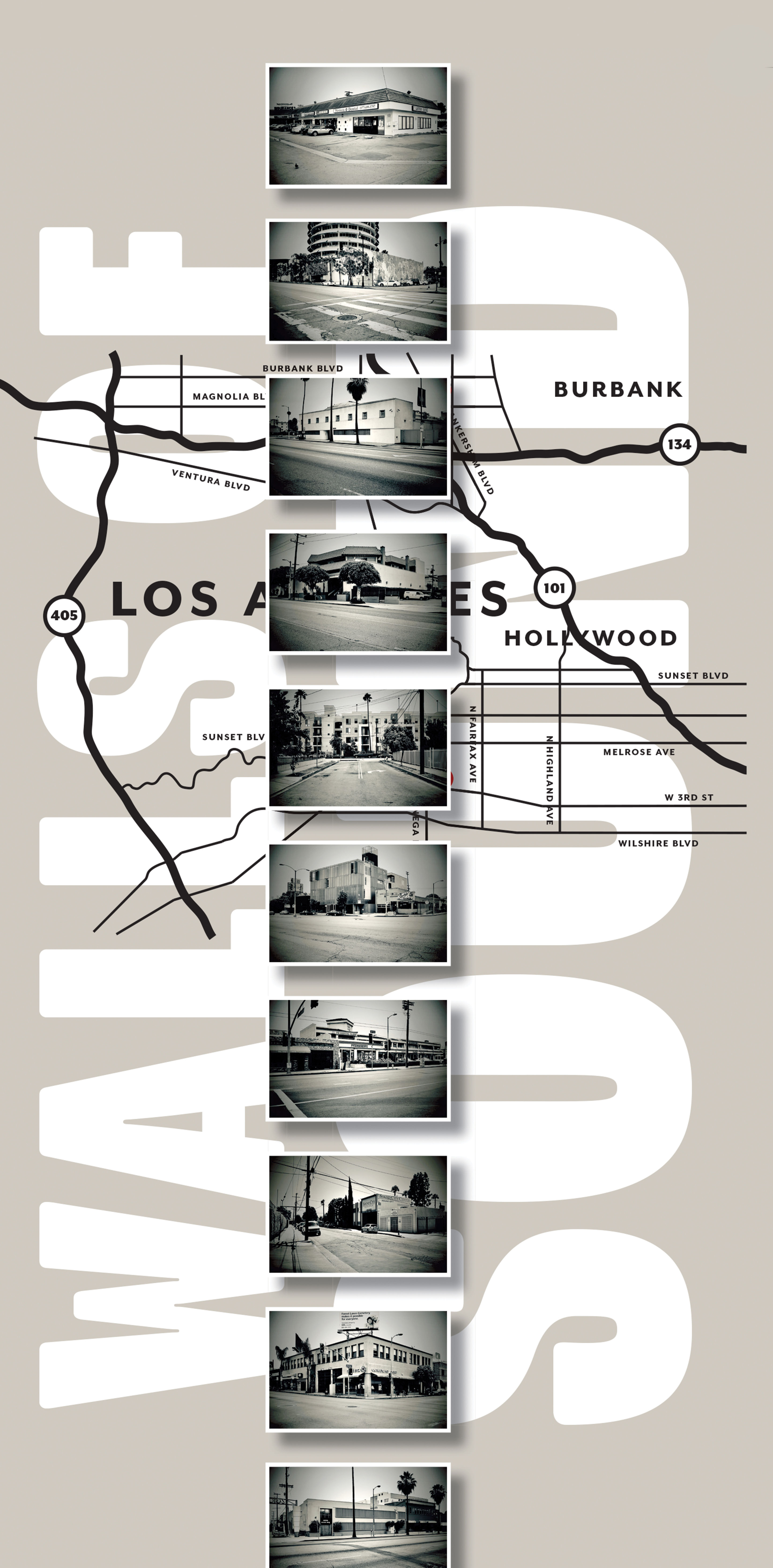

I moved to L.A. the summer of 2017. Right now I'm purely freelance, working out of whichever provided studios, but I definitely have aspirations to have my own spot. I want to have the ability to have folks over, but it's frustrating. I can't do that right now because my house can't really accommodate that. I'm working towards having my own room and am looking forward to that.

What kind of rooms do you like?

I like studios that are a bit contained. Where you can choose to have ambience or not, depending on where you put up a microphone. But really, I'd stress the control room the most. With a control room, you want a sanctuary of possibility. The best-sounding control room you can pull off will really inspire something you didn't think was possible. That's what makes a studio great. [I find] the playback in a lot of studios is difficult to trust. It's really hard to fight acoustics in control rooms, but if I'm in a studio where I make one or two EQ moves and I suddenly realize I'm piloting the experience super easily, I quickly see how it's the room helping me do that. If the room is making me feel comfortable and I trust it, I'm able to stretch so much further than I thought I could. It's seldom that I've been in quality rooms like that, and it makes wanting my own room even more urgent.

How did you get into recording?

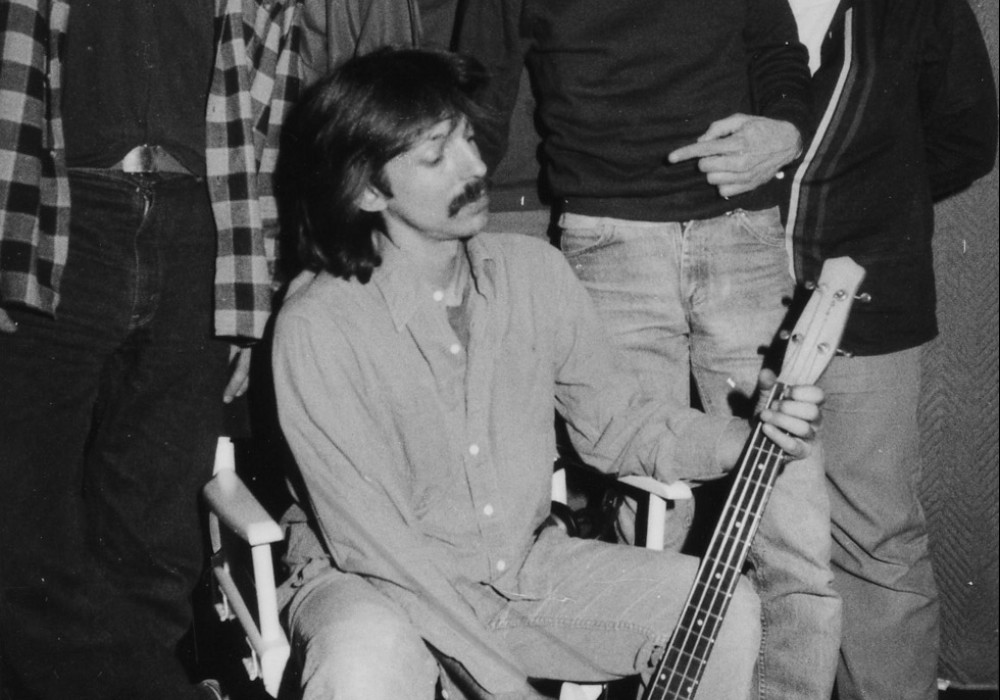

I started as bass player when I was a kid. When I was 11 or 12, my friends and I all decided one afternoon that we would start a band covering Green Day. At 14 to 18, I was making really hilarious compositions with GarageBand and Logic for my friends and I to have a laugh. If you pull up the "tenor sax" MIDI patch in GarageBand you can't not smile. I flirted with hip-hop beats, which didn't last all that long. I would go onto the iTunes music store and go to the "electronic" music category to find cool album covers, which would later reveal themselves as Burial and Four Tet. I got very absorbed in finding out how they did it.

You ended up at Berklee, which has a great reputation.

Yeah. It's a very expensive endeavor – thank you, Dad! There is an advantage to having SSL and API [consoles] everywhere for your training, but it's insane to think people need to spend that much money to become considered "trained." It helps getting used to gear that is in common studios you may go work in but, at the same time, I would say I resent gear culture.

How do you mean?

I firmly believe the chemistry of people working together, or having peace with your vulnerability, will bring you better results than any piece of gear can. Is it even worth listening to a bad song recorded well?

What is Berklee like?

You have people like Susan Rogers [Tape Op #117] as your instructor. I remember we had a project to deconstruct a song, re-record it, and try to make it sound like the original recording. I picked the Bon Iver song "Skinny Love." I was doing this sound-alike with a few friends who also went to Berklee, trying to get them to sound like Bon Iver, and I couldn't get it. I went to Susan and had a mini breakdown, telling her, "This is impossible." I'll never forget when she smiled and said, "Andrew, that's exactly the point."

That's great! Should a vibe start differently for every project, or do you try and recreate acoustic fingerprints in advance for an artist based on input they gave before you start?

It's a cop out to say it's different on every project, but really, it is. There are a lot of typical processes we go through working on records, such as hearing "reference tracks," and I find there is never really "the best time" to hear someone's reference tracks. It's never like, "Before we start, let's have a listen to music you...