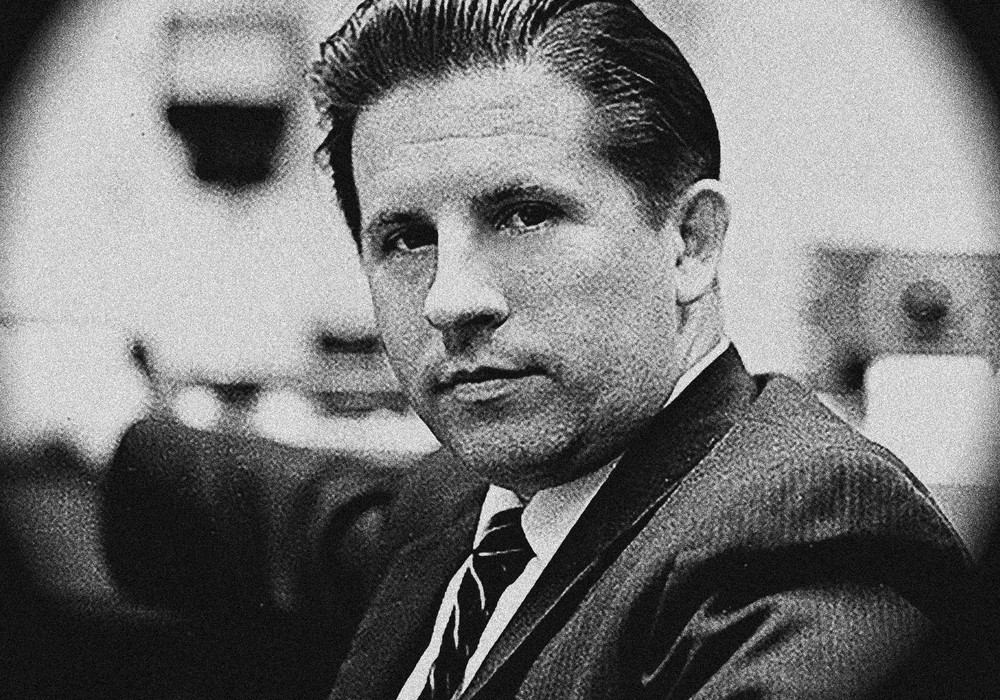

Jamaican electronics whiz kid Hopeton Overton Brown got his moniker "Scientist" from none other than one of dub music production's founding fathers, King Tubby (Osbourne Ruddock). As a teenager he began engineering and mixing out of Tubby's, later moving to Channel One and Tuff Gong studios. He is one of the genre's most prolific and creative forces, while also remaining a sought-after mix engineer and producer. In addition to his own impressive, if not stunning body of solo work, he has worked with Jamaican legends Bob Marley, Roots Radics, Sly and Robbie, Peter Tosh, and Horace Andy, to name just a few. Meanwhile, current artists such as Hempress Sativa, Ted Sirota, and Khruangbin have all benefitted from his otherworldly presentations of their music. To watch him mix is like watching man and machine become one. His mixes are dance-like performances on the console, and the sound pictures he paints are mystical and dreamlike. I tracked Scientist down and had the pleasure of digging deeper with one of music's unique geniuses.

What is dub?

Dub is the first electronic music where an engineer becomes a composer and an the artist. I developed techniques to leave the mind while keeping the mind wandering. That's basically dub. A composition from the engineer.

I know it's a popular genre, but I'm always amazed at how many engineer and producer friends who are not familiar.

Yes. Because here's what: Straight-up engineering, you record whatever band [you're working with] and nothing's altered. Everything is just how the musicians played it. With dub, now we have to recompose it. One element is the element of surprise. How to keep it all together and get the listener hooked on one pattern, and also how to switch up the pattern. Now what I can tell you is that every time you listen to a dub track, it never sounds exactly the same. Each time things sound a little bit different, and it is part of the reason why these records last over 30 years; because I've developed techniques of how to put things into the music so that each time you hear it, it sounds a little bit different each time. It's always going to remain fresh.

When you were a teenager and had an interest in electronics and fixing TVs, winding transformers and repairing amplifiers for sound systems in Jamaica, how did that play into you coming to work with King Tubby?

Because I wanted some parts for the amplifier I was building. I was introduced to King Tubby by a friend who lived in my neighborhood.

And getting some components from King Tubby?

Yes.

What was it about being there at the studio with him that attracted you to producing music as well as mixing?

Well, King Tubby's [Presents The] Roots of Dub was an inspiration to me the first time I heard it. I liked what was going on. It was a good album to test the amplifiers that I was building, because of the frequency response.

At what point did you have an opportunity to get behind the console?

Well, I actually made him a bet after being at the studio. We had a workshop, and my primary thing was to help to wind these transformers, fix whatever televisions and whatever amplifiers that would come in there. Then, by being there, I started putting my theories together about how to mix music. But prior to that, I thought I could build a console. When I got out to the studio and first did studio work, I found that my theory in building recording consoles was not really a one-man operation. I started talking to him about features he might like, things like moving faders and automation. To him, it was a joke. One day he made me a bet. He said, "I bet you wouldn't know the first thing to do." Because I was exposed to the studio by watching, and because I was an electronic engineer at that time, he lost his bet, basically.

What did you learn from him about setting up the console that was specific to dub mixing?

I'm a self-taught person. I got to see what I learned and observed. "Okay, whenever I hear that sound, this is how it's done," or, "This is how to do it," whether I had no knowledge of the studios back in those times to validate my theory. I read books about recording. I didn't have any prior experience. It was a 4-track machine. By being there, I started using my electronic skills to evaluate the theories that I had in my head. So, he gave me a wonderful opportunity.

Dub mixing is such an extraction and a breaking down of the music to its essential core. Would you say that that is true?

Yes, because I have developed techniques of how to make the music not become monotonous. A lot of the time, if you just mix the music and play it, it doesn't have anything to keep the imagination going. As you know, remix was started in Jamaica, and then here comes the hip-hop and everything, and it's after remix.

Was it simply the availability of things like reverb, tape echo, and...

The rest of this article is only available with a Basic or Premium subscription, or by purchasing back issue #136. For an upcoming year's free subscription, and our current issue on PDF...

Or Learn More