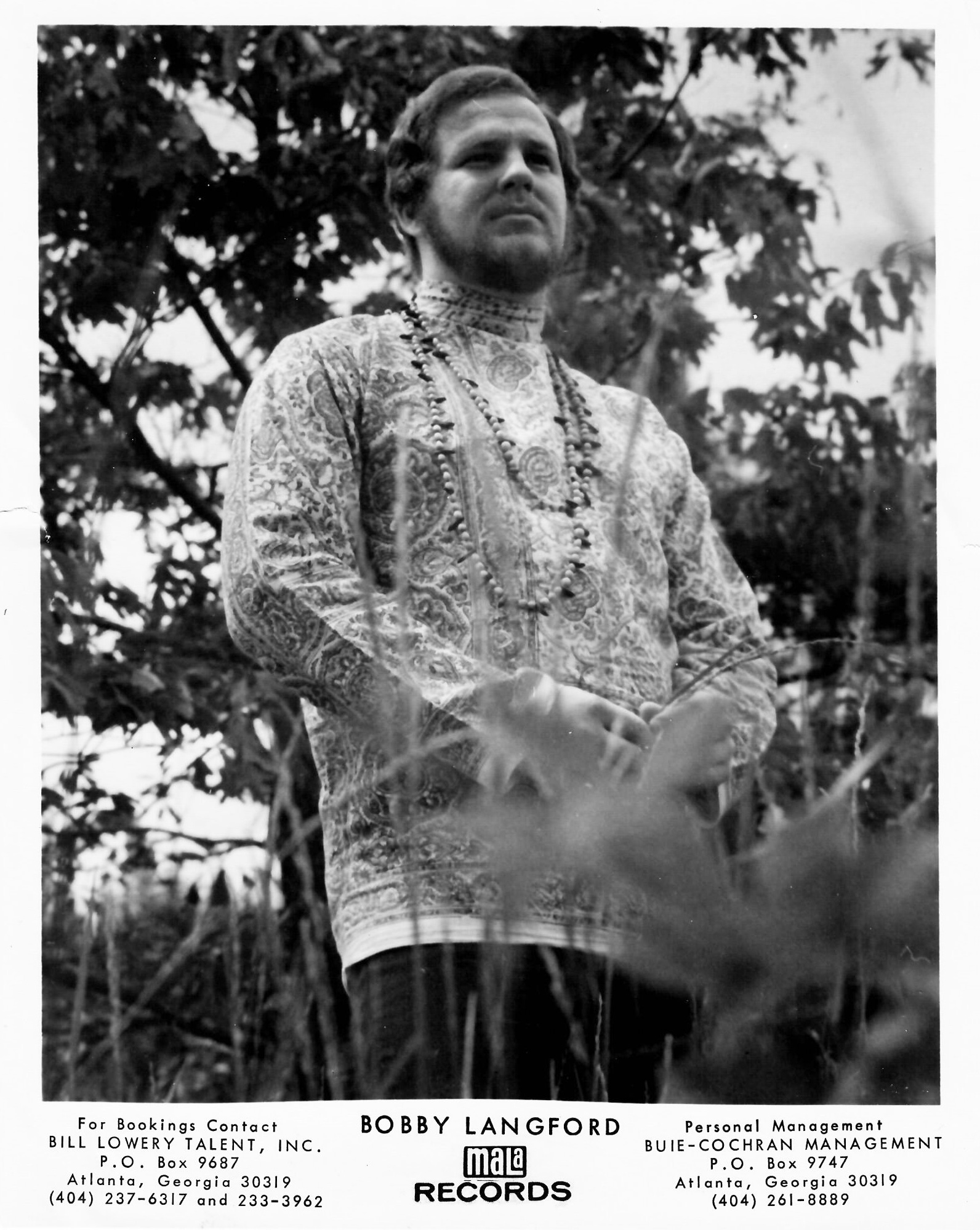

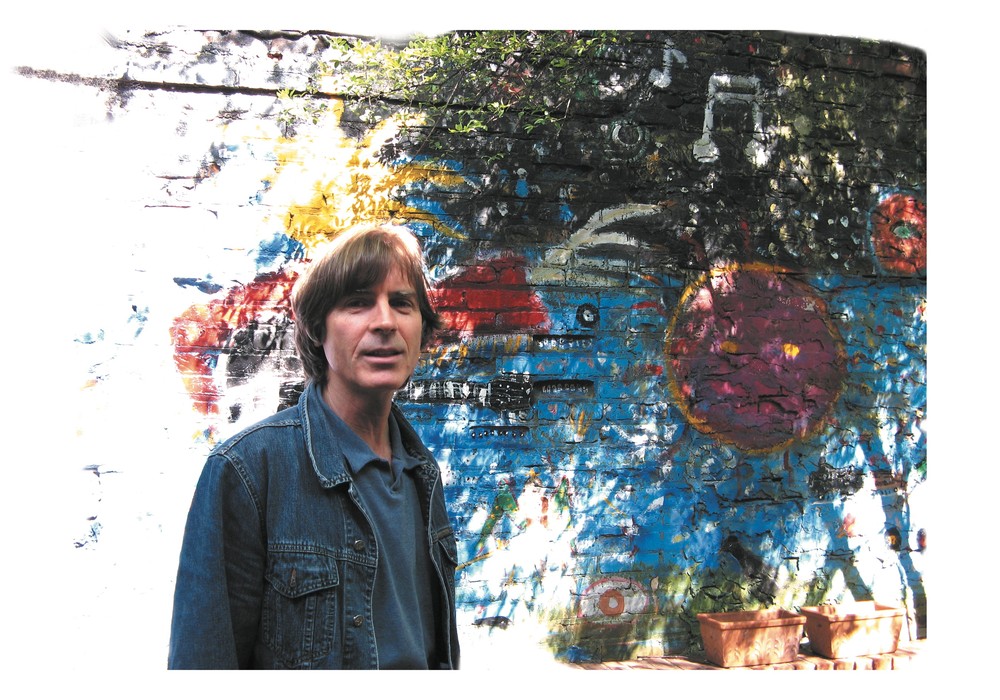

Youthful and energetic at 76, Bob Langford is active in local politics and community affairs in his small town an hour north of St. Petersburg, Florida. But in the late-1960s he was part of the bustling Atlanta recording scene, and a participant in the birth of southern rock. Bob is easy to get to know, but his modest demeanor scarcely hints at his many careers: recording studio engineer/ owner, entrepreneur, singer, inventor, electronics wizard, and even restaurateur. Today, between meetings at the local historical society in his various advisory roles, Bob also records local bands in a small studio next to his home.

How did your career begin?

I guess my career in music started in the '50s. We had a doo wop group in high school in Louisville, Kentucky, although I was more into classical music at the time. We played sock hops all around the area, made some recordings, and the radio station played them. They were local "hits." I had a chance to go to Juilliard [School], but I didn't want to be a music teacher so I passed it up. I moved to Florida with my parents in 1960, to a small Gulf Coast town north of Clearwater. In the early-1960s, after high school, I was the singer in a band traveling around Florida. We used to play in a little place in Cocoa Beach. We'd be on the stage, and suddenly all the windows would light up and everyone would run outside. It was a rocket going off, just up the coast at Cape Canaveral! Bertie Higgins was the drummer in the band. He always wanted to sing but we wouldn't let him. I guess he got the last laugh [with his hit in 1982, "Key Largo"]. About this time I got hooked up with a promoter and manager named Bill Lowery, who managed Jerry Reed, Ray Stevens, Joe South, and a bunch of other performers. I also met a guy from Dothan, Alabama, named [Perry] Buddy Buie, who managed Bobby [Robert Charles] Goldsboro and others. Buddy and his writing partner, J.R. Cobb, wrote all the Classics IV and Atlanta Rhythm Section hits. I moved to Atlanta to work for them in 1966, doing promotion, management, band booking. We were just down the hall from Bill Lowery's recording studio, Master Sound. In that room they cut hits by Billy Joe Royal, The Tams, the Classics IV, and the first Atlanta Rhythm Section. Besides doing promotion, I was a background singer and I sang on a lot of these records, plus a lot of jingles like Coca-Cola and Orkin Pest Control. I went from singing to doing percussion, like cowbell, tambourine, and congas. A lot of times we would play percussion at the same time we did background vocals.

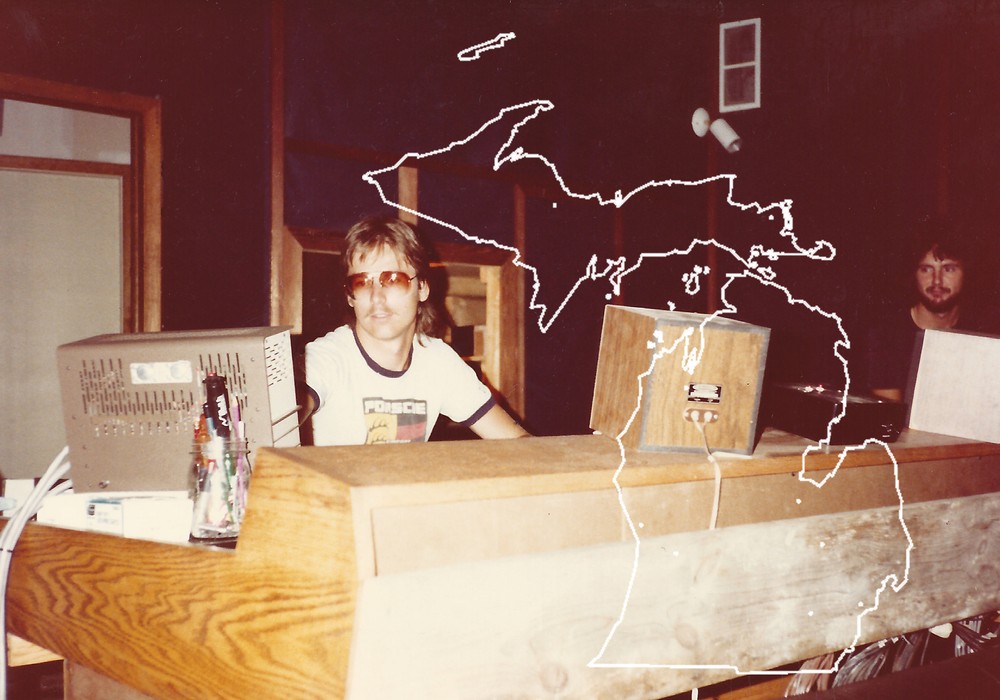

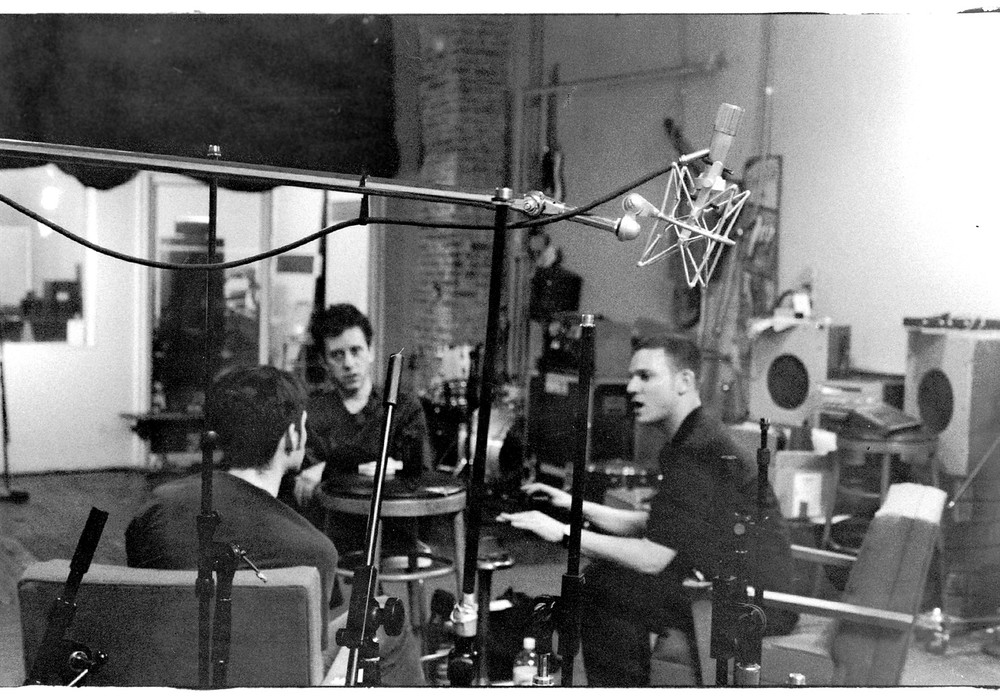

What was studio recording like at this time?

Things were done very quickly. In those days, a union session was three hours and you were expected to cut at least two, maybe three sides in that time. At Master Sound they recorded on two Ampex 350 1/2-inch machines, with tube electronics and the great big meters. Everything was rack mounted. It was more like a glorified radio station. I think the board was a modified Gates radio board. It had these big 4-inch knobs, and your channel assignment was this lever switch with three positions – left, center, and right. For EQ we had a couple Pultec equalizers. Everything was patched – they had this huge patchbay in the rack, all balanced at 600 ohms. They had an EMT plate, but they also used a live echo chamber that was an old septic tank beneath the building. Next to the studio there were railroad tracks, and any time a train would come by they'd have to stop recording. They would always begin by cutting the bass, drums, piano, and guitar –the rhythm section – on one track and the vocal on one track.

So they would record on one 3-track machine and then mix that to another 3-track while adding more tracks?

Exactly. You could only go three generations [of tape submixing]. You'd have to always be thinking ahead of what you planned on putting on there. You'd have to equalize [tracks] going down, with tape hiss and all. You would have to push some frequencies, knowing that you were gonna lose those in the generations. You'd also have to push everything up at the beginning of the record, and then bring it back down as the song went on.

You wanted to keep above the noise floor, if the beginning of the song was quiet?

Right. We'd have to plan it out. Not many things ran direct in those days. They did a fuzz...