Joining Abbey Road Studios as a runner at the age of 16, John Kurlander swiftly moved up the ranks to become a tape operator and assistant engineer. Working under the tutelage of Geoff Emerick [Tape Op #57] and "fifth Beatle" George Martin, Kurlander's first major role was as an assistant engineer on The Beatles' Abbey Road LP. Known for his studious attention to detail and note taking, Kurlander was promoted to first engineer within two years and worked on solo albums for former Beatles. Additionally, he also worked alongside full orchestras, which saw him tracking and creating arrangements for artists including Elton John, Supertramp, Ozzy Osbourne, and Everything but the Girl. Kurlander would later move into the world of West End and Broadway musicals, video game scores, and film soundtracks. He is currently best-known for engineering and mixing the soundtrack music for The Lord of the Rings trilogy, earning Kurlander consecutive Grammys. With the recently expanded reissue of The Beatles' Abbey Road – the last album that the group recorded together, there's no better time to reminisce on Kurlander's extraordinarily accomplished career.

You visited Abbey Road, or EMI Studios as it was called at the time, at age 13. How different were the studios back then?

It really couldn't be more different. I lived around the corner, in St John's Wood, and used to walk past the studios every day. When I was 13, my school class and I were invited to do some sound effects for a drama recording. That was 1964, and The Beatles were recording in Studio Two. All of their equipment was set up at the far end; we were told we could look at it, but not to touch anything. That obviously created a huge impression on me. When I was 16, I had the option to leave school and I wanted to work in a studio like EMI. In those days, there were a lot more studios in London than there are now, but EMI replied to my letter immediately and asked for an interview. It seemed like a piece of cake; they just asked some basic silly questions and offered me the job two or three days later.

And you believe getting that job was a fix?

Well, I used to go to a school called Quintin Kynaston on Finchley Road, and after I'd worked at the studios for about six months I came out of the front gate and saw my English teacher walking past. He asked how I was getting on, and we had a little chat that was very knowing. I figured out that he'd fixed it, because he was the next door neighbour of the studio's assistant manager at the time. He didn't tell me he'd fixed it – it was implied; but how else would I step into a job like that?

Did your interest lie more in the technology over working with musicians or bands?

It was both. When I was 11 years old, I got a tape recorder and used to play piano and overdub, so I loved the idea of all that. You know what it's like living in Abbey Road; while The Beatles were recording there were always 60 to 70 girls outside, and it just became part of your life. It's difficult to explain to anyone who didn't live through it, but the British music scene was the centre of the world at that point, and I was one traffic light away from it.

You oversaw the renaming of the studio...

I was the second engineer, or tape op, on the Abbey Road album and I was at the session when the band decided to change the name. It was going to be called Everest, and The Beatles were planning to go to the foothills of Mount Everest to take a picture in the snow with the mountain in the background. That day, Paul suggested scrapping that idea and just taking a picture in the street and calling it Abbey Road. I witnessed a change, because EMI Studios was the closest thing to being the BBC – there were lots of rules and regulations about what you could and couldn't do. About three years after the album was released, our studio manager, Ken Townsend, got permission from EMI to rename the studio. Even after Abbey Road came out there weren't lots of tourists coming to take pictures. It was only after it got renamed that the whole mythology began.

You were working as a runner initially, but used to take notes on everything?

The first job in those days was working as a third person in the tape library. I'd take ten tapes down to Studio Two or Three and hang around, getting to know who everybody was, as well as how the whole system of tapes and labelling worked. That role was for an unspecified time until the next vacancy came up, which could be anywhere from six months to a year or more. I only lasted three months. They called me in at Christmas and told me that when I came back in the new year I'd no longer be in the library, I'd be a tape op. Even more unheard of, I was only actually an assistant for another two or three years, because after the Abbey Road album Geoff Emerick was set to produce a Badfinger album [Straight Up] but asked myself and another tape operator, Richard Lush, to engineer it instead.

Do you think it was your studious observation of sessions that fast-tracked your career?

You could call it studious – I'd say it was OCD! Geoff liked that it was part of my nature. Because everything got documented, he felt comfortable that I could help him set everything up. It's worth mentioning that I'd just turned 18 when I worked on Abbey Road and Geoff was 24, but he'd also started when he was 16. When you look back, this famous album was basically made by kids. Geoff was hardly a senior engineer at the time, but there is a contributing nature to the fact that everybody who worked on that album was so young.

I guess we think of an engineer as someone that requires many years of experience to fulfill the role. Obviously, that's not always the case?

It's true in certain areas but, jumping ahead again, I was asked to do a classical recording with the Liverpool Philharmonic in 1974. It was a big 90-piece orchestra and I was only 23 years old at the time. I remember asking the producer how he felt about me doing it, as I'd never recorded such a big orchestra, and he said, "Personally, I don't care if you screw it up as long as you don't feel bad!" [laughs] He knew I wasn't going to screw it up, but it was nice of him to say so even if he didn't really mean it.

So, you felt you were able to learn in a rule-breaking environment?

Geoff Emerick was doing experimental stuff because he always wanted to try new ideas and move forward. From that perspective, it was perhaps beneficial that he didn't have years of preconceived ideas, because when John Lennon would say something to Geoff he didn't have that baggage to say, "No." There were so many establishment rules. For example, you can't have the microphone closer than so many inches from the bass drum, but Geoff didn't care. When he did "Eleanor Rigby" he'd use the microphones a bit like how you'd use contact mics now, putting them so close to the violins that the players were scared they might damage them.

In those days, engineers were more likely to be thrown into the deep end – sink or swim – and under those conditions people usually come out the right side?

Yes, you've got it; absolutely. When Geoff asked me to work on what turned out to be Abbey Road I was obviously nervous about screwing up, particularly with tape, because if you spooled it too fast it could all jump off. I remember George Harrison saying he really liked a solo and he asked me if I could punch it in at the second verse. But if I punched in a millisecond early I knew it would be erased forever and I'd have had to say to George Harrison, "Sorry, but that bit you loved so much is gone." These days, everything's backed up; but that option didn't exist then. You had to have a completely different mindset.

The Beatles' "The Ballad of John and Yoko" was one of your first big assistant roles. How did that go?

Working with just the two of them [Paul and John] made it a lot easier. There was something magical that happened when the four of them were together in the same room; but when there were just two, and I'm not talking about John and Paul in particular, you didn't have the same feeling that it was a big deal. "The Ballad of John and Yoko" was also recorded and mixed in about eight hours, which was quite the opposite of how The Beatles records were made. I guess the fact that it was made so quickly – and we had a stereo master mix at the end of the evening – made me think, "Well, that was easy!"

Were those speedy recording sessions due to budgetary constraints, or something else?

The "Ballad of John and Yoko" was done at that speed, but the rest of the album wasn't. John had married Yoko, written this song and had it all figured out. The two of them came in to do it and played every instrument, but that's an untypical example. The actual Beatles album sessions started at the end of May, generally around lunchtime, and would continue up to around 4 a.m. What's funny is that they were supposed to come in around 1 p.m. but sometimes wouldn't show up for hours. All the girls outside the studio had an inside track on their schedule, so if we came in for a one o'clock start and there were no girls outside, we knew they weren't coming, and sure enough they didn't.

Was working on the Abbey Road sessions a creative environment, or did it have more of a technical feel?

When we worked on the album it was a mixture. On two or three tracks the tapes had originally started life earlier with the Get Back sessions, which we found filed with the Let It Be project, so they'd either continue from there or decide to start again. Most of the songs started afresh that summer. There had also been demos lying around; they'd go into the studio, sit around a piano, call George Martin in to help them and get his advice on certain things like voicing of chords or song construction. They'd record for around two hours, so we'd have three or four reels of backing tracks of the same song at different tempos and so on. Then they'd come up and listen intently for another few hours, but not just to the last take – they'd want to hear everything. At that point, we might start editing or choosing a master. Maybe they'd come back a week or two later and start from scratch in another key or different tempo. On the musical side, it was like a workshop. But, technically, it was before the days of having a lot of outboard gear available, so they would often ask our technical department if they could build something special to be tried out. From that perspective, a lot of the effects and technologies we used were developed on-demand.

Was it also your job to create an ambience that would get the best out of them?

No, the roadies did that. [laughs] Every night there'd be a couple of policemen walking the beat around the neighbourhood, and in the winter it would get quite chilly. Around midnight, two policemen would come into the building for 15 to 20 minutes and be given a cup of tea by security. The reception area was different to how it is now, but the swing doors were still there. If you looked down the corridor, you'd see this fog of marijuana smoke and the smell came right through to the reception area. The two policemen were happy as Larry; they couldn't care less.

Were you on strict orders not to partake?

For what I was doing I really needed to keep a clear head. The only strict order I could remember was about wearing a shirt and tie – and one night I got told off by the management for loosening it. There's a picture of me around that time looking unbelievably nerdy, which was not how most people would have imagined a Beatles session to be.

There's also funny story of Paul asking you, late one evening, what your favourite album was?

I was so tired at the time because it was two or three in the morning and he asked what my favourite album was. Without skipping a beat, I said, "Pet Sounds." I look back now and think, "How could I have said that?" But I was only 18 and he was great. We started talking about what sort of influence The Beach Boys had when The Beatles made Sgt. Pepper's.

What do you cherish the most from the Abbey Road studio sessions?

It's a difficult question to answer. I realised it was an important thing to be working on, but within a year I'd forgotten all about it and it became just another record. It's only after you've realised it's the last one that it takes on any significance. Being the tape op, I was writing down notes, lyrics, and chord charts, but when I went home in the evening I wasn't able to show any of that to my friends – we had to be professional about it. Seventy percent of the songs were written in the studio, so it was amazing to hear this music, not just being recorded, but coming together.

There were tensions within the group prior to the recording of the album. Was that something you noticed at the time?

From everything I'd heard "The White Album" was the worst, from that point of view. The people who worked on that told stories that you wouldn't want to hear, but when The Beatles made Abbey Road they told Geoff Emerick and George Martin that it wouldn't be like that. For the most part it was really friendly and happy. One of the things that everyone talks about is Yoko having a car accident and having a bed brought into the studio. Some sessions were in Studio Two and others in Studio Three, so the roadies would not only have to move all the instruments and mics but also the bed. Most of the time people understood, because John had this very new relationship with Yoko and that was respected, but every now and then things would flare up. But it's important for young people that work in studios to remember that these are very restricted memories, and it's not really professional to tell tales about who screamed at whom.

What's the story behind the track "Her Majesty," where the tape was left on the cutting room floor but you subsequently added it in?

We'd done rough mixes of every song that was going to be on the medley and, up until that point, those tracks had all been on separate reels. To join them up we used a crossfade technique, which basically meant using three stereo machines. You'd play song A on the first machine, at the changeover point start machine B, and then record the crossfade on the third machine. We did the crossfades, but it was my job to edit them. After putting the medley together, it was two in the morning and everyone was tired. Paul said he didn't think that "Her Majesty" worked very well in the middle of the medley; he told us to get rid of it and went home. So I unpicked the edit and joined "Mean Mr. Mustard" into "Polythene Pam." However, there was a short bit of tape left over on the floor. If it hadn't been so late I'd have just thrown it in the bin, but I followed the rule that said if you ever remove anything from a master tape put it at the end of the reel with a long gap of red leader. So, I used that rule, stuck "Her Majesty" at the end and, as the story goes, the next day it got cut as a reference lacquer, was played to the guys, and they loved it.

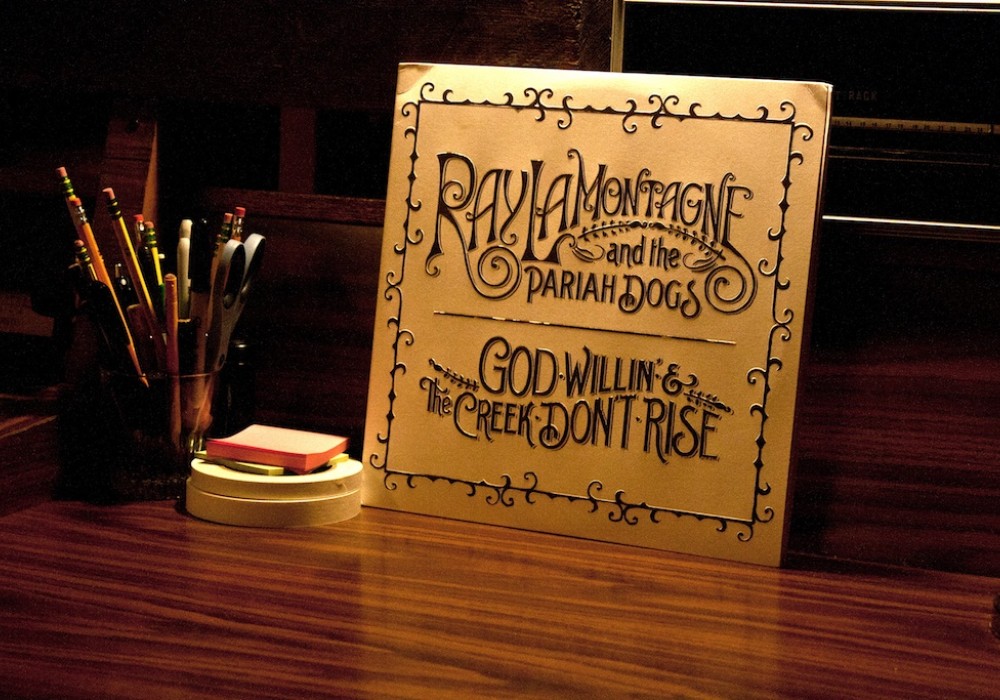

Fifty years after the initial recording, do you have an opinion on the remastering of Abbey Road, or remastering in general?

I had no part in the remaster and before Geoff died last year, he wasn't involved in any of the remasters either. I know a lot of people have views about that, but it doesn't really bother me. We made the best mix we could at the time using what we had. It was mixed for vinyl, and when you cut vinyl there's a lot more restrictions on what you can do compared to CD or a digital release. The idea that we've now got 50 years of technology validates the remastering process. I know some people have said it shouldn't be touched, but if people want to hear the original, they can still access it. Of course, there's also a curiosity about outtakes, and there's two ways you can argue that. Some would say they chose the right master so why would you want to listen to a version they didn't choose? Others are really interested in the whole development of a record. If I had a criticism it would be that they could have done a mono mix, because a lot of people prefer the mono version of the stereo mixes. We never made a mono of Abbey Road, and it would have been a great opportunity.

You went on to record symphonies and musical theatre, which some might think is a logical progression, but what precipitated your move into film scoring?

Movie scores became part of life at Abbey Road in the '80s, and I was already doing a lot of classical and orchestral overdubs for rock bands. One of the most famous ones I did was the Toto IV album, which used a lot of samples, electronic rhythms, and an orchestra. So I felt that film scoring was already halfway between doing a legitimate classical recording and orchestra for rock bands. At the time, I was always looking out for new challenges.

With film, you're obviously working to visuals, but would you agree music can be visual, in that artists tend to create mental concepts to write to?

I've always thought that when you're making music for records it's for people to listen to. Not all, but a lot of film scores are music that you hear but don't really listen to – it's there as an aid to help you emotionally connect to the film. With some of the best film music, people often say they didn't notice it, which can be one of the highest compliments. We're not talking about the main theme, but the music underscoring the body of the film. In the last few years I've been doing increasingly more music for video games, and that's really interesting because people listen more to video game music than film music. It's almost a step back into making records.

You worked with Peter Jackson on The Lord of the Rings, and I read he was quite impressed that you still have that habit of taking notes?

Yes, absolutely! [laughs] We recorded The Lord of the Rings in four different rooms, over a period of three years, at four different locations, edited everything in-between, and it all matched. That wouldn't have been possible if it wasn't for my ridiculously OCD note taking. I was talking about that one day with Peter, and he said it's a bit like the continuity supervisor (also known as a script supervisor) they use on films to make sure people are wearing the same clothes. It was the EMI way, but I find it really useful to have this library of notes going back years that I can refer to every now and then.

What's your relationship with technology been over the years? You grew up with analogue and now so much is digital. Did you fully embrace that?

I was up for digital right from the start. It was really rough to begin with, but very few people know that EMI built a digital desk as a prototype in the mid-'70s, so we had an experience of what digital was capable of way earlier than anyone else. When digital took over I thought it was about time, because analogue was made for mono, stereo, 4-track, and 8-track. But when it got to 16-track, we started to need Dolby noise reduction because we were now getting 16, 24, or 48 tracks of noise. By the time you were totally dependent on noise reduction it was probably time to move on to something that didn't have any noise – then it just needed time for the sample and bit rates to improve. The Beatles were always interested in new sounds and in moving forward; that's what I learned from working on the Abbey Road album. Today, you can still get great sound on digital, but it takes a bit more hard work.

So even today you feel those technologies fulfill very different functions in production?

There are people who really love the sound of analogue and make records in a way that couldn't be done in the digital realm, and they wouldn't want it to. So, there is a divide and I don't think the fact you can record at 96 or 192 kHz brings you closer to analogue, it just means the sound quality is better than it was. The magic that analogue creates in people's memories is the simplicity of making music with less tracks. If you want to make a great-sounding analogue record, apart from the gear, you need the discipline to make it with fewer tracks.

How would The Beatles have been different had they had digital technology?

They'd have done okay, because they'd have kept moving forward and pushing things to the limits. Obviously, they had solo careers, but it was so much about the songs – that was the key.

What projects are you working on at the moment?

Blizzard Entertainment are one of my regular clients, and they make video games in the States and all over the world. Together, we work on games like World of Warcraft, so I do most of the recording on that, as well as other projects like Overwatch. I guess I've always liked new challenges and to keep things fresh and moving.