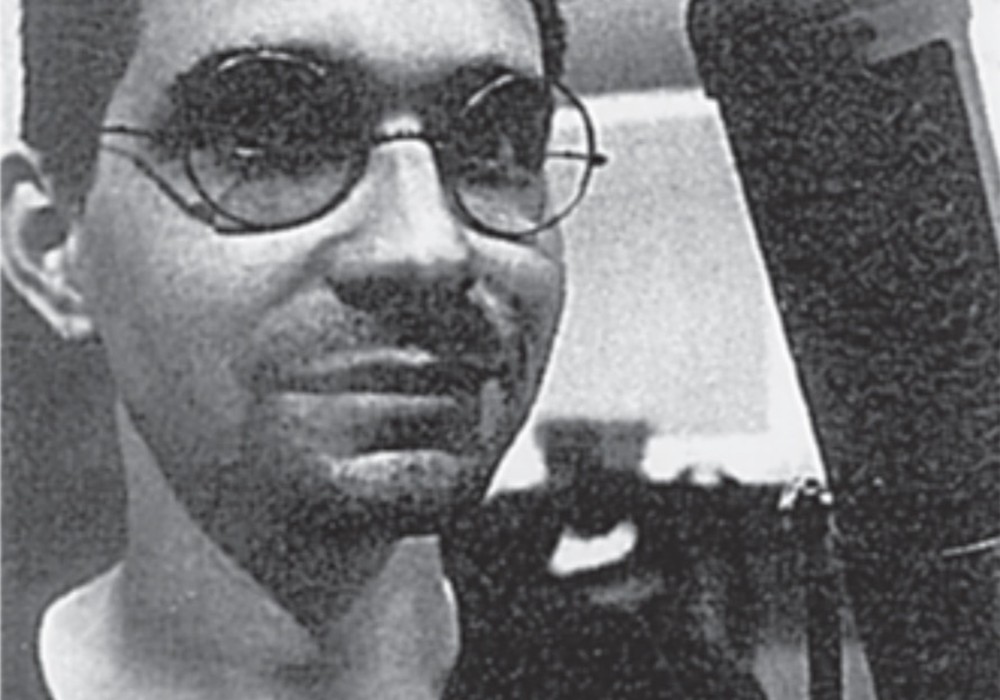

Waylon Albright Jennings, known as “Shooter,” is the child of famed “outlaw country” luminaries Waylon Jennings and Jessi Colter. But how did he end up producing artists like Brandi Carlile, Marilyn Manson, Duff McKagan, and Tanya Tucker, plus winning Grammys along the way? And how in the world does being a Nine Inch Nails fan factor into this? We had to track him down!

You’re from a musical family, but at what point did you realize, “I like the recording aspect”?

As a kid, I loved going to the studio with my dad. I was young, but I remember that I loved how the board and all the gear looked. I remember going to Chips Moman’s studio [American Sound Studio] in Nashville when I was probably four or five years old. He had a poker machine in the front, and I thought that was the coolest. A lot of people get bored with the studio process, but I remember loving it and trying to understand it. Recording was what I got into about music before anything. I didn’t have a desire to play on stage; I still don’t. As much as I love playing shows, and have loved that part of my life, the touring and getting up and performing in front of people was never something that I had a knack at. When I was about 13 or 14, I discovered Nine Inch Nails. That was the musical catalyst that made me decide I wanted to play music. Even though I come from this family, and have a lot of experiences from that, it was that band. I was captured by the fact that this dude [Trent Reznor] was doing all this by himself. It wasn’t a live band. These were records that were constructed. Nine Inch Nails was the first time that I got into a band and said, “I want to make music like this.” I found out he used this product called Studio Vision Pro by a company named Opcode, so I saved up money and I bought that program. Any time I saved up allowance I would go to Sam’s Music in Nashville and buy a different MIDI brain. A “drum” brain or a “sounds” brain. I still couldn’t afford a recording method, but Studio Vision Pro allowed two or four channels of real audio, so I would play guitar and then I could do a vocal. The rest of it was all live-triggering MIDI. I finally was able to afford ADAT, and I remember feeling, “The floodgates have opened. I have eight tracks of audio that I can record and sync with all of this MIDI.” Instead of going to college, I asked my parents for a Pro Tools unit, and they got me one that was good enough for home recording. After that, I moved to L.A. and took my Pro Tools rig with me. To answer your question, I was probably 13 or 14 years old was when I started with the recording side and getting into it.

When your dad made records, I’m guessing he didn’t make them using MIDI!

Yeah. It was a necessity for me, because I wasn’t cool in school. I had two buddies who were guitar players, and they would play on stuff because I couldn’t play guitar. I didn’t hang out with a group of dudes and decide to form a band; I was alone. This offered a way to make music without other people being involved.

It’s interesting to transition from being somebody who learned the craft on their own, to becoming a producer, which is such a people job.

You’re right, it is a people job. It’s also a “streamlining of communication” job. When I work with artists, they end up trusting that I’m going to steer this ship and know the right and wrong decision. That I know which way to go, and I can see ahead of the curve a little bit. That’s part of the job. I did Marilyn Manson’s We Are Chaos record, and we were talking about Trent Reznor. Trent always had a guy who was programming with him – whether it be Chris Vrenna or Atticus Ross – and I didn’t realize that. I’d always thought he did it all by himself, so I was training myself to do it all by myself, like him. He’s really an organizer. I work with an artist as a hands-on project, in which I’m going to be involved in a lot of aspects. [I treat it] like I’m doing one of my own records. It...