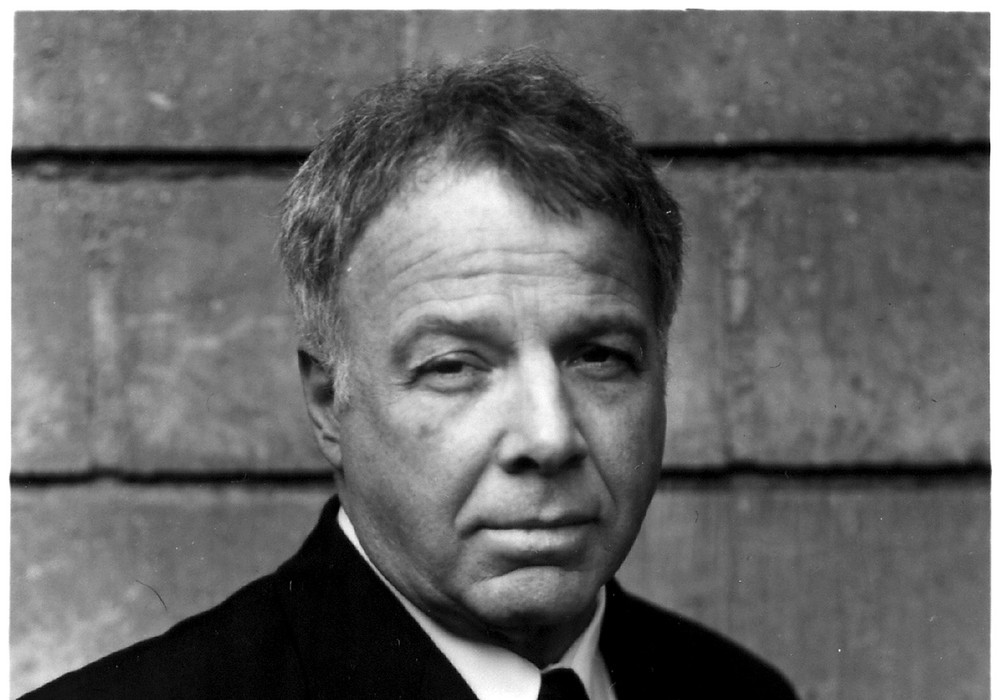

Plenty of engineers and producers migrate from one side of the glass to the other: at some point, an engineer realizes she’s happier on the technical side, or a producer discovers his knack for getting the best out of bands in the studio. These changes often happen more organically than by conscious choice. Sheldon Gomberg’s transformation has been different from most.

“You always have a choice,” says Gomberg, speaking by phone from his personal studio in Los Angeles. “You can give up, or you can find something to do that may not be what you set out to do, but you find that you love it just as much.”

Gomberg, a former guitarist and bass player who built a career as a session ace in a variety of genres, has suffered from Multiple Sclerosis for more than two decades. He went from studio and stage gigs with Rickie Lee Jones, Kenny Wayne Shepherd, Warren Zevon, and many more to a successful recording and production business, working with Fistful of Mercy, Ben Harper and Charlie Musselwhite, Jackson Browne [Tape Op #105], and others. He absolutely loves his work. He wishes he could still play, but he is surprisingly cheerful, and he’s got a lot to say about making music and accepting the hand you’re dealt. I talked to Gomberg about his studio work, from playing in Seattle underground bands and sleeping on sofas, to his L.A.-sized success playing sessions, to becoming a producer and giving back to the music community.

Tell me about your first experiences with music; how did your interest develop?

I had this cool [Jimi] Hendrix poster on my wall, and I had this cheap acoustic guitar, and I wanted to play leads like Hendrix. I didn’t know anything about it, so I tuned the strings up high so I could play high, and I broke the string. It made me so mad that I was like, “Okay, I’m going to learn how to play this thing.” Stubbornness and determination were what set me down that path. When I was about 15, I wanted to get into a particular underground band in Seattle, The Knobs, and they called me one day. They said, “Our bass player quit. Do you want to play bass?” I said, “I don’t play bass,” and they said, “We’ll teach you.” I said, “I don’t have a bass.” They said, “We have one.” I said, “I don’t have an amp,” and they said, “We have one.” I thought, “Let me get in the band. I’ll ace the guitar player out and get the gig playing guitar.” The drummer, Drake Eubanks, was great and taught me about what bass and drums did together, and I fell in love with bass. I still played guitar, but the bass became my main focus. The connection of bass and drums in support of the melody and harmony – everything about it was so great.

This was when you were still high school age?

Yes, but I left school when I was about 16. My parents weren’t happy about it, but I knew what I wanted to do, so I moved out. I moved in with the singer of this band and got a job at a restaurant downtown as a busboy/dishwasher/prep cook while I was playing in bands. We were together for about a year, playing in the underground scene of Seattle in the ’70s. Then I quit my job and the band broke up, so I couldn’t afford to pay my 90-dollar-a-month rent. It was understood that I had to move out. I got another job, but I had nowhere to live. I worked the night shift in a restaurant, and when I was finished working I would sleep there until the cleanup crew came in the morning. I would walk around waiting for my friends to wake up. That didn’t go on too long – just until I got enough money together to move into another place. The drummer and I started another band, ’S Nots. Later, I ended up getting into a band with the old guitar player for The Knobs, and when I turned 18, he and I moved to San Francisco. We were living in a flat on 29th and Mission – a three-bedroom flat with 13 people in it – and Jello Biafra was one of the guys who lived there. That was right when the Dead Kennedys were starting to take off.

Do you remember the first time you recorded in a commercial studio?

The first time was in Seattle when I was about 16. That was in the ’70s, and my band went into Robert Lang Studio. It was in a two-car garage, at that time.

In those early days, were you pretty fascinated with studio work?

I’ve always loved studios and recording. In mixdown, everybody in the band would have their hands on the faders. But I didn’t have any idea that it would become the path that I went down. I was totally focused on being a musician.

What would you say was your first real professional gig as a musician?

My first professional gig was in San Francisco in 1981. I played with Randy Hansen, who does a Hendrix tribute. He was on Capitol Records, and he ended up doing the soundtrack for Apocalypse Now. That was a lot of fun.

What studios did you record at while you were in the Bay Area?

I remember working in The Automatt – the old CBS Studios. That was a great place. I worked there. David Kahn worked there, producing Pearl Harbor and the Explosions. I was also working at a music store called Studio Instrument Rentals. We rented equipment to all the shows and we had rehearsal rooms. Santana, Journey, Montrose, Eddie Money, and all kinds of bands would rehearse there, so I got to know everybody in the San Francisco music business. The drummer for Santana, at the time, Graham Lear, was the first one to say to me, “You should move to L.A. for what you’re trying to do.” I did move to L.A., and I started working for other people. It was great, getting to play all kinds of different music and not having the headache that comes along with trying to keep the boat afloat when you’re in a band.

How did you begin making connections in L.A.?

There was a lot of word of mouth, and meeting people. One time, I auditioned for this band and they wanted me; they called me and said, “We want you to play bass, but Bob Ezrin [Tape Op #31] is going to produce the record, and he wants to hear everybody again.” I auditioned again, and when I finished, Bob took me outside and said, “You’re one of the best bass players I’ve heard in this town in a while, and you’re too good for this band. I want your number.” He got me on a Julian Lennon demo. Then a friend, [drummer] Rob Brill, called him one day; he was in session and there was something wrong with the bass player. Bob told him to call me. I went down and did the session, and we got along great. We became a rhythm section around town, playing with different bands, and in different styles of music. We both had that passion to play all different styles. We played together for about 15 years. Everything started blossoming and growing, and pretty soon I was playing with people I idolized as a kid.

You toured with some of those artists as well, correct?

I did a short tour with Michael Penn [Tape Op #53] and a little playing with Rickie Lee Jones in the ’90s. I was Warren Zevon’s last touring bass player. I did some work with Kenny Wayne Shepherd, as well as some out-of-town [gigs] with Peter Himmelman and Eleni Mandell.

Did you see one type of playing – studio or live – as more your thing than the other?

I love being in the studio, but you need that live interaction, too, and the immediate response from an audience to keep your chops up. When you play live, it makes you raise your game. You need all of it.

Did you play upright bass as well? What were your favorite basses and amps during that period?

I’d say it was about 50/50 upright and electric. My number one bass was a ’62 [Fender] P-Bass with flat-wounds [strings]. I also used a ’59 [Fender] P-Bass and a Kay bass – the one that became known as the “Sheryl Crow” bass. I also had an old ’64 [Fender] Jazz bass with flat-wounds. For amps, my favorite was the old Ampeg B-15 flip-top, and if it had to be bigger than that, I would probably use a Gallien-Krueger 800 with an [Ampeg] SVT-410 cabinet. Another one of my favorite bass amps – though it wasn’t very practical – was an Acoustic 360. I used to take one of the power amps out of the cabinet and rackmount it, using that with the 360 preamp and going through the 4x10/1x15 cabinet.

Were you a collector-type – somebody who was always looking for gear?

Yeah. I loved vintage stuff, and I would keep my eye open for it. But once I found the ’62 P-Bass and the Kay, that’s mostly what I stuck with.

When you were working in L.A. studios then, were there certain engineers you especially enjoyed working with who informed your production work?

I loved working with Ethan Johns [Tape Op #49]. I worked with Marvin Etzioni; he used me for sessions a lot. But, as far as developing my style, it grows out of who you are. I don’t mean that I didn’t learn from great engineers and producers. I did. But I also learned from people where the experience wasn’t always great. I tell people this whenever they are going to work with me: if you see something I do that you hate, good. Learn from it. I’ve seen producers sometimes pushing artists in directions they didn’t want to go, and I would think, “Wow, I never want to put my stamp on music that way.” I want to find out who the artist is. That’s what I did as a hired bassist; I’d try to find out what it is they need, and give them that. It’s the same thing in producing. I want to know who they are and develop and encourage that.

What were your favorite L.A. studios from your session days?

When I was recording with my own bands, we worked at Lion Share [Recording Studios] with an engineer named Larry Ferguson. It was the old ABC/Dunhill [Records] studio, but when I was working there it was Kenny Rogers’ studio. There were three rooms there, and we used to record in Studio C. It was a great room, with an API console. Then we would mix in the other rooms. We also liked Hollywood Sound [Recorders].

Looking back, is there a point you’d identify as the peak of your success as a musician?

In ’96 or so I started playing with Rickie Lee Jones, and she was one of my favorites – somebody I grew up idolizing. Getting to play with her was gratifying. I also got to record on albums with Ryan Adams and Five for Fighting. Playing with Warren Zevon and Kenny Wayne Shepherd was a lot of fun, but I would say that when I got to play with Rickie, that was a personal milestone for me.

When did you first exhibit symptoms of MS?

I used to restore old ’38 and ’39 Lincolns, and one time I was under one, reaching up and bolting something to the firewall, and I couldn’t feel the bolts. Oddly enough, that makes it hard to do anything. You still know how to tie your shoe, but you can’t do it because you can’t feel it. It’s weird. Suddenly my hands and feet were numb. That was the first sign of it. And we chased it for a year. I went to a neurologist; he kept sending me to different doctors, and they kept pricking me, prodding me, jabbing me, and shocking me. No one could tell me what was going on. I was having to grip the neck of the bass harder all the time, and I was getting carpal tunnel, so I thought maybe I just had carpal tunnel. You start thinking you’re crazy because nobody can find the problem, but you know there’s a problem. Finally, my neurologist sent me to a back doctor who examined me and said, “There’s nothing wrong with your back. You need to go see this other neurologist.” So, I walked into the neurologist’s office, and he was on the phone, but for some reason I could tell that, after all of these doctors I’d been to, he was going to tell me what was wrong. He got off the phone, asked me a few questions, and took my MRI scans. We walked in the other room and he threw the scans up on a backlit screen, and before they stopped shaking, he said, “Here’s your problem.” I was like, “What? It’s that simple?” He knew right off the bat. If I had gone to a doctor who knew what he was doing a year earlier, we might have been able to curtail some of the damage.

What year was that? Were there any helpful medications at that point?

This was in 1995. It was kind of at the beginning of medicine coming out for this. What they could have done for me at the very beginning would have been to put me on steroids to reduce some of the swelling and scarring, but the ABC drugs – Avonex, Betaseron, Copaxone – did not come ‘til a year after that. When they did come out, I got on them right away.

What does MS do to your body?

My best understanding – and I don’t even know if the experts have it 100 percent figured out – is, we all have T cell helpers in our white blood cells. When we get sick, the T cell helpers go out and kill the “bad stuff.” But for people with MS, there’s a flaw, and those T cell helpers recognize your myelin, the milky sheath that coats your nerves, as the “bad stuff,” and they attack it. This is what causes the scarring. It acts like an electrical wire when the coating has been rubbed away; like putting an electrical wire against metal. Your nerves are shorting out, and depending on how much damage has been done to the myelin, there can be nerve damage if enough of the myelin is eaten away. Everybody’s case is different, in terms of severity, as well as in terms of the scarring and the sensation. With me, I sometimes feel like I’m getting an electrical shock. I told my doctor one time, “Sometimes I feel like I’m getting shocked with a 9-volt battery.” He said, “That’s because you are.”

Does it hurt?

Mine doesn’t hurt. It’s odd, though. Sometimes when I’m tired my leg will start twitching because I’m getting an electrical shock. It’s a very weird feeling.

Once you knew what was going on, what were your expectations?

Oddly enough, when the doctor told me I had MS, I was relieved, because at least I knew what it was. I didn’t know much about the disease yet. I had seen the ARMS Tour [Artists for Research into Multiple Sclerosis] in the ’80s, when Jeff Beck, Jimmy Page, and Eric Clapton were touring to support Ronnie Lane from the Small Faces. Ronnie sauntered to the front of the stage, and I felt bad for him. That’s all I knew about it, but I was like, “Okay, there’s the possibility that it’s going to get worse,” but it seemed like that was far in the future. And it was far in the future. I went ten years before anybody knew I had it. Nobody could tell; there were no outward signs. But then around 2006, it went over a cliff, and that’s where most of the trouble that I have now came from. There was a two-year period when it went south, and then it leveled off.

Keeping it secret for ten years seems like a lot to carry around.

There were a couple friends I told, but I kept it pretty close to the vest for two reasons: one, I needed to continue working, and I didn’t know how people would react. I actually had one situation where I was talking to a friend on the phone and I asked him how his band was. He said, “I had to fire the guitar player. He has MS, so you know he’s going to die.” I thought, “Okay, I can’t tell people.” The second reason was, I didn’t want people to treat me differently. I didn’t want them trying to get the door or carry things for me. I wanted to be treated normally.

And you kept on playing on sessions all that time.

I kept playing until I started having trouble walking, which correlated with having trouble playing. I continued to play in the studio for many years, but I finally stopped a couple of years ago. I’d always told myself I didn’t want to be that guy in the room that sucked. When I became that guy, it was time to stop.

Was there a specific point you can remember when you acknowledged to yourself, “I’m a producer and engineer now, not a musician”?

I thought I’d be a musician ‘til I dropped. I had done some production work for fun, but I’d considered it a side gig. But then, as I started physically declining, it was there and I fell more and more into it. One day I thought, “Okay, I guess I’m a producer.” And thank god it was there, because I don’t know what I’d be doing right now. To be able to reinvent myself at this point in my life, and to be able to do it with something I love almost as much as playing – there’s nothing as great as playing, but it’s a close second and I’m happy with it. I was lucky.

By this time did you already have your studio? What is it like?

Yes. I have a main live room that’s about 20 by 20, as well as a couple of smaller iso booths that I use for guitar amps, vocals, or acoustic guitar. There’s also a keyboard room, and I have a control room that’s about 22 by 12 with a Quad-Eight Coronado console. I’ve had a Quad-Eight since the beginning, though I replaced the original with a different one a few years ago.

Did you work with a professional to design the rooms?

Working with the rooms available, I bounced ideas off of a friend of mine, Carl Johnson, and came up with a design. Then I had George Augspurger come in the room one time. He moved the speakers for me, and he said, “This is where you want these, and put a carpet here,” and it sounds great.

Do you use Augspurger monitors?

No. I have ATC SCM45s. I went through a bunch of different speakers, because I kept feeling there was something I wanted that was missing. I ended up finding it in these ATCs.

How has your health changed since you started working out of this studio? Have you needed to make any modifications to the rooms to accommodate your condition?

I can no longer sit in a chair. I stay in the scooter when I get in the studio. Also I have guys working with me now, whereas before – if I wanted to – I could work by myself. But, as things went south, I couldn’t set up microphones, so I had to get an assistant. Now I need to have someone with me, and I have some great guys who work with me and we co-engineer. Jason Gossman and Bill Mims have been with me a while, but then Jason ended up getting a touring gig with the Red Hot Chili Peppers. Now he’s working with them and Metallica, so he’s less available. But Jason Gossman and Joe Chiccarelli [Tape Op #14] had recommended Bill, and he’s been my other main guy for five or six years. Both of those guys help me a lot, and when they can’t make it I have a couple of other great engineers I can call, such as Morgan Stratton, Kevin Smith, and Larry Ferguson.

On the subject of asking for help, can you talk about the ways that Sweet Relief Musicians Fund and MusiCares have helped you as well?

When I first started having trouble walking, I used a cane, but when that started not being sufficient I transitioned to a scooter, and, when I did that, I could no longer walk up the stairs into my house. So I had to put an elevator in, and that was rather an expensive endeavor. I called Sweet Relief and they helped me, but they are smaller than MusiCares so they also introduced me to someone at MusiCares, and they helped me with the lion’s share of it. Between the two organizations, I was pretty much covered for the purchase and installation of the elevator, and that was overwhelming. I have a hard time accepting gifts, though I needed it, so later I thought, “Sweet Relief used to make these benefit records and they haven’t done one since 1995.” So I said, “How about if I do another record for you to help repay you?” It’s not like they wanted repayment, but I wanted to make the gesture.

That’s when you made the compilation album Sweet Relief Vol. III: Pennies from Heaven.

Right. I got to work with a lot of great artists I love. It was a lot of fun, and I helped them put a little money in their coffers.

Who participated, and how did you choose the material to go on the album?

About half of them were friends of mine, and half were newer to me. Ron Sexsmith was one of my favorite artists, and I hadn’t worked with him before that record. I reached out to him and to Sam Phillips, Shelby Lynne, and kd lang. I didn’t know Jackson Browne at the time, but I knew everybody in his band, and one of my friends made the introduction.

Did the artists come to your studio, or did you fly some of the vocals in?

That whole record was done at my place, except for one overdubbed track and that was the Ben Harper version of the Van Morrison song “Crazy Love.” We had tracked the song live at my studio, and I said to Ben, “How about if we get vibes on it? It would be great to get Gary Mallaber, who played the original vibes on it with Van Morrison.” Gary is a great drummer and vibes player, and I’ve played with him a bunch. So, I sent it off to Gary, and he recorded that part at his place. That’s the only outside track. Gary told me an interesting story about that, too. When they were doing the record [with Van Morrison], he was looking around the studio and he couldn’t find his mallets. So, they ended up finding some screwdrivers with rubber handles and he played those. When I called him, he said, “You want me to do that?” I was like, “Hell, yeah!” So he played our track with screwdrivers, too.

You’ve worked with Ben Harper a lot. How did that start?

I was working on a Rickie Lee Jones record, and through doing that I was dealing with one of her managers, who was also working with Joseph Arthur. He said, “Joseph Arthur is coming through town. I want to bring him by, show him your place, and see if he’d like to work there.” He brought Joseph by and we got along great. Joseph liked the studio, so he said, “Okay, let’s put some dates aside.” Then the manager called back and said, “Actually, we’re going to do a Joseph Arthur and Ben Harper record.” Then Ben texted Joseph and said, “Do you know Dhani Harrison?” And Joseph texted back, “No, why? Is he in our band?” [laughter] Dhani came by as well, and the Joseph Arthur record turned into the band Fistful of Mercy. They wrote all the songs together and we cut all the basics in three days. Ben and I got along really well, and he wanted to come back and work with me.

Can you share some details about laying down tracks for the first Ben Harper with Charlie Musselwhite album, Get Up!?

Everything was pretty much live on that record, with the band set up in the same room. For the first couple of days, Charlie wasn’t there, so we had to overdub his harp on a couple of songs; but once he came in everyone cut live, and then a lot of the vocals were overdubbed. They’d run the song a few times and recorded it. They’re all such great players; it didn’t take long to get those takes. It was all very organic and natural. We left everything set up for a week to ten days, and laid everything down to Pro Tools.

Did Ben ever sing live while he played guitar, or was it only guitar going down live?

I don’t believe he ever sang with guitar, because we wanted to capture them clean, but there was a song [“All that Matters Now”] that we cut live in the control room with Ben and Charlie sitting together and singing. We grabbed mics and ran them in with them sitting right next to us at the console.

Ben Harper has talked about the importance of mic placement on that record – how the distance between him and his vocal mics helped re-create the sound of old blues records. Can you talk a little about the vocal mics and where you situated them?

We had two mics set up on Ben – an AKG C 12 and a RCA 77-DX – and the placement depended on the song, whether they were put side by side, or one was across the room to get a room sound. It also depended on whether he was 2 or 3 feet from the mic, or 6 feet from the mic, or right up on it and distorting. Or we might put one mic on Ben and have the other mic reflecting off the door to give a natural room sound. I’m pretty sure we had those mics going through Neve 1073s.

Who was your assistant on those sessions?

Jason Gossmann started the first few days and got most everything set up for the band, and then he went out with the Red Hot Chili Peppers and a guy named Erich Talaba came in. Bill Mims was going to finish it off after Jason left, but Bill couldn’t make the first few days, so Eric worked for two days and then Bill came and finished the rest, including all of the vocals. He was also with me when I was mixing.

How did you capture Charlie Musselwhite’s harmonica? He has his own custom amp, doesn’t he?

Yeah, he does. He used that and the Gibson Skylark that I have. He really liked it – so much so that he ended up buying one of those for himself. I’m not sure of the mics we used on those amps, but I imagine it was a [Shure] SM57 and a Royer R-121. Charlie’s great. He’s always in a good mood, and he’s always got a little one liner; a little joke. He’s a lot of fun to be around. And Ben and Charlie have a great working relationship. I didn’t steer Charlie to do any one particular thing; that was more between Ben and Charlie.

When you’re mixing, do you need help to manipulate your console or Pro Tools system?

No. When I’m mixing, what I need help with is patching gear in. If something’s hard for me to reach, I can ask my assistant. Jason, Bill, and I are at the point where they know what I want; I don’t need to tell them much.

Those relationships are so important for any engineer/producer, but they’re especially important for you.

Yeah. I couldn’t do without it. Those guys are much more than assistants. They’re engineers on their own, and I’m lucky they work with me.

How did If You’re Going to the City: A Tribute to Mose Allison come together for Sweet Relief?

Don Heffington and Amy Allison have worked together over the years, and they’ve known each other a long time. Don and I have also known each other for ages and worked together a lot. Don suggested to Amy, “You should do an album of your dad’s songs,” and as they started to get into the idea of it, Don said, “You need to meet Sheldon. We should get him on this.” He introduced the idea to me and I loved it, and we all started throwing out names of people we wanted to be part of it. Amy’s list had a lot of people she knew who were attached to her dad, were fans of her dad, or had done his songs. Don and I had different suggestions, and we took it from there. Once we started seeing who was interested, it got to the point where we almost turned it into a double record because there were so many people who wanted to be involved.

One of the most striking tracks on the album is the Tippo Allstars, featuring Fiona Apple, on “Your Molecular Structure.”

That track was all cut live in my studio. Fiona was not feeling very well during that session, but she was a complete trooper and she is amazing on that song. The band was Don Heffington playing drums, Sebastian Steinberg playing bass, David Garza on guitar, and Benmont Tench on keys. There were no overdubs on that, and it was done in a few hours, soup to nuts.

What keyboards did Benmont Tench play, and how did you record him?

He played piano on that, and that was mic’d up with an AKG D19C right in the center of the piano, inside the top. He likes mono piano, and I used that mic because it gives an angsty rock ’n’ roll sound.

He played your studio piano?

Yeah, it’s a 1916 Wing & Son upright grand.

What was your drum mic’ing scheme for Don? Did you have one setup throughout the project, or did it change from song to song?

I didn’t stick with one particular thing, but I do have typical ones that I will use, like a [Neumann] U 47fet on the kick drum, along with an [AKG] D12 or a D112, depending on what I’m going for. Sometimes I’ll use an Audio-Technica ATM25. I used a SM57 on the snare, but I’m not a huge bottom snare mic fan. Sometimes you need it, sometimes you don’t. On the Fiona track, it was a U 47fet on the outside of the kick and a D112 on the inside, bused through a dbx 160. For the snare, it was a Shure SM57 through a Neve 1073 and a dbx 160. The overheads were done with a Shure SM2, and the room mics were Royer R-121s through a Smart C1. The toms were Sennheiser MD 421s through Distressors, and then again I used an American [Model] D-22 smashed through an Altec 436 [compresser].

As one of the co-producers, was Don hands-on, in terms of tech choices?

He’s not too strong on the tech, but he has a good ear and he knows what he wants to hear.

You also have Dave and Phil Alvin on the Mose Allison album, doing “Wild Man on the Loose.” Had you worked with either of them before?

I had never worked with Dave or Phil before, but the great thing about the record is that everybody involved were such huge Mose Allison fans. People wanted to do it practically before we even asked them, and I think that passion comes out in the songs. The community loves this guy.

They definitely sound amped on their track. How did you capture Dave’s guitar amp?

It was a Shure SM57 through the Quad-Eight console and a dbx 160x. I love the sound of his guitar on that, especially the solo – it’s screamin’. That track, as well as Val McCallum’s guitar sound with his Firebird on a Lucinda Williams track I did, “Somebody Loan Me a Dime,” are the two favorite guitar sounds that I’ve ever gotten. But that’s also because their gear sounds so good and there’s no way to screw it up!

Did Phil sing live with the band?

Yes, into a Microtech-Gefell M582 through a UREI 1176.

His voice sounds beautiful on the album, and so does Chrissie Hynde on “Stop This World.”

Chrissie was fantastic. She got so into it. She kept telling Amy, “You’ve got to get this person,” and she was also the one who brought in Iggy Pop [“If You’re Going to the City”].

Did Chrissie come to California to record her track with you?

No. We cut the band track live in my studio with Don Heffington on drums, Bob Glaub on bass, Mark Goldenberg on guitar, Fred Tackett on guitar, and David Witham on [Hammond] B-3. Mark sang a guide vocal, so everybody knew where the track was, and then I muted his vocal. She recorded her vocal to the track in London at SARM Music Village with [engineer] Dave McCracken.

Were any of the tracks made 100 percent outside of your studio?

Yeah, in this case the Ben Harper and Charlie Musselwhite track, “Nightclub,” we did it at The Village, but I mixed it at my place. Jackson Browne recorded “If You Live” at his place, but I mixed it at my place. Loudon Wainwright III did his [“Ever Since the World Ended”] by himself and sent us the completed track. Bonnie Raitt’s version of “Everybody’s Crying Mercy” was done live in concert. Frank Black did his in New York. Iggy Pop did his in New York and Miami, but Don and I added some percussion to it and I mixed it here. Anything Mose recorded, like “The Way of the World,” was done in New York also. Robbie Fulks did “My Brain” on his own; Taj Mahal recorded “Your Mind is on Vacation” on his own as well. Richard Thompson’s “Parchman Farm” was another live thing. And then Amy’s track with Elvis Costello, “Monsters of the Id,” which closes the album, was an existing thing that had been done years before. That was recorded at Don’s place.

Can you talk about what this project has meant to you, both musically and in terms of your ability to give back to Sweet Relief?

I’ve done a bunch of records now for Sweet Relief, and giving back for what they did for me has been great, but it’s also a lot of fun to put these albums together. This Mose Allison album is a record I’d have loved to do even if it wasn’t for Sweet Relief. But when Don told me that Amy wanted the money to go to charity, I said, “I work with Sweet Relief, and they help musicians.” And she said, “That’s great. I love it.” So that feels good. The problem is, most of us fools who have chosen music as our lives go into it with no parachute. We assume we’re going to make it work and support ourselves for the rest of our lives. Most of us are not covered or ready if a disaster hits, and that’s why MusiCares and Sweet Relief are there to help when they can. They can’t help everybody in every situation, but I’ve seen them help a lot of my friends, and it’s amazing.

These groups not only help musicians, but also they’re sustained by musicians. What have you observed, in terms of the generosity of your community?

The situation with our healthcare system right now is that people are chronically ill and politicians kick them to the curb. Well, the music community and the artist community are not like that. They’re always willing to help. If a musician gets sick, other artists do fundraisers or whatever they can to help. The Sweet Relief records I’ve been doing are perfect examples. Artists come together and donate songs to help other people who need it. Sweet Relief also helps artists do a lot of fundraising through an artist’s peer group. And a big-name benefactor will often come through and donate a lot of money to help get someone off the streets or get them into the hospital, and nobody knows about it necessarily. It’s because artists who have a lot are ready to help someone in need.