In the alternate reality where everyone still reads recording credits off of their album sleeves as the record spins, we would see the name Leon Michels on many of them. Having worked with household names such as Lana Del Rey, Dr. John, Jay-Z and Beyoncé, The Wu-Tang Clan, and Adele, as well as projects with his own bands The Mighty Imperials and El Michels Affair, who recently released the album Yeti Season, should make him a known quantity. Leon currently splits his time between New York City and his home upstate. He recently sat down for a couple of conversations about his process, love of analog, disdain for high track counts, and being purposely bad at Pro Tools.

What was your early path to music, and what got you interested in recording?

Whenever anyone asks me about that, usually the only answer I can come up with is that I had really good teachers and got inspired pretty young. I got put in jazz bands and had teachers who put me onto cool music. As far as recording goes, the first time I was ever in a studio was with the band The Mighty Imperials – my first band with Homer [Steinweiss] and Nick [Movshon], both of whom I still play with – a “heavily inspired by The Meters” organ quartet. We recorded for Desco Records. That was our first time in the studio. My first experience was all on tape with Gabe Roth [Tape Op #59]. I was spoiled with that being my first experience. When I started recording music on my own, I was gifted a Tascam 388, which is that home 1/4-inch, 8-track. It has a mixer built into it.

Those are cool.

I put it in my bedroom and started messing around. It took off from there. I got that machine in my room the last year of high school. Or perhaps it was my first year of college. That was the beginning of it.

You’ve stayed on this path of a very organic music style and production.

I grew up playing jazz. My whole approach to music – even my approach to engineering and recording music – it’s all performance-based. Before I even started recording music, it was always about a performance, or improvising and capturing a performance.

What were some of the early records that you were into?

When I was pretty young my teacher put me onto early jazz, like Benny Carter, Benny Goodman, Johnny Hodges, and Duke Ellington. In fifth or sixth grade, I got pretty obsessed with jazz.

What instrument were you playing at that time?

I was playing saxophone. That was when my love for music started, with popular jazz from the ‘40s and ‘50s. I got obsessed. When I’d be searching for music, I would find artists like Lou Donaldson – the funkier side of jazz. I started listening to more of that, and that led to James Brown and The Meters. By that time I’d met Philip [Lehman] and Gabe [Roth] from Desco, and they turned me on to all the deep funk shit.

Tell me a little bit about your studio.

There are two studios. There’s one studio in Queens, which is the studio I share with Homer and Nick, who were both in The Mighty Imperials with me in high school. They also play on all my records, and I play on the records they produce as well. We’re best friends, and I’ve known them since I was 13. Then there’s also Thomas Brenneck, who’s a producer for Charles Bradley and guitar player for The Dap-Kings. We all share a studio in Queens. That’s a real, proper studio. Control booth, live room, and isolation booth. In addition, we pooled all our gear together so we have a pretty extensive collection of microphones, tape machines, and outboard gear. I start most projects there. Then, since I’ve moved upstate, I have this barn that’s attached to my studio. It’s a smaller production room with all my favorite little pieces of gear. I don’t have that much, but I have keyboards I use all the time, as well as a drum set, and a piano. That’s where I finish all my records.

Is there any special equipment that are your “desert island” pieces?

Well, in Queens, everything goes to a 1-inch, 8-track MCI. That’s how it starts. The pieces of gear I use here the most are a 4-track cassette [recorder], which I love processing through. I have a Binson Echorec, an Eventide [Instant] Phaser, an AKG BX10 [spring reverb], and an Echoplex.

A lot of tone-shaping and tape-based effects.

Exactly, yeah. I like when a piece of gear has a very specific EQ curve that, even if you pass [signal] through it, it does something cool.

When I listen to your records, they are a very interesting mix of that old sound. But your aesthetic and sensibilities are quite modern at times.

Oh, that’s good to hear! Thank you. I’m definitely not a purist. I use Pro Tools on 100 percent of my projects. I’ll never only do tape, because it’s too damn hard to finish a project on tape. But everything I use is all like a process. It dictates how the product moves forward, in a certain way. I like tape because it limits me, but then Pro Tools also gives me some freedom. That’s why I like my 4-track cassette. I’ll start bouncing tracks down. If I’m looking at a Pro Tools page and have more than 12 or 16 tracks, it drives me nuts to look at. If I see too many tracks, I start to get anxious.

That’s the trap of digital production. We don’t have to make decisions.

Yeah. I’m not very good at Pro Tools, which I want to keep that way. If I was, then I probably could handle more than 16 tracks. But anytime anyone ever tries to teach me how to use Pro Tools better, I hear white noise, because I don’t want to know how to use it any better.

You’ve had the opportunity to work with some pretty amazing artists. Some of it through your relationship with Dan Auerbach [Tape Op #127], like Lana Del Rey’s Ultraviolence.

That was a pretty incredible experience, from my perspective. I had been touring with The Black Keys around 2010. Dan cold-called me, because I put out the first Lee Fields record, My World, which he liked. They were looking for a bass player and a keyboard player for The Black Keys live. I started touring with them and we got on well. I started doing sessions with him in the studio. The first thing we did in the studio, outside of The Black Keys, was a Dr. John record [Locked Down]. Then Lana was maybe a year later.

Were Dan’s workflow and sensibilities similar to yours?

Oh, yeah; absolutely. Dan’s workflow was like my workflow on speed. I make decisions quickly. If it’s not working, I’ll move on. Dan does that, but he also works 12- to 15-hour days. He works nonstop. He also has the means. His studio [Easy Eye Sound] is crazy. He has every piece of gear and every fun little toy. I’ve learned a lot from Dan. Dan’s incredible in the studio.

If somebody comes in and you’re producing them, what’s your approach to that? How is that similar, or dissimilar, to Dan’s approach?

It’s different with every artist. Some artists come in and they respect what you do. They say, “I want to collaborate and make something where we don’t know what’s going to happen. Whatever happens, happens.” That is cool and fun. Then there are people like Lana who have this hyper-specific idea of what their music is, what it should sound like, and anything else is just trash. Which is a crazy environment for someone like myself, or Dan, who’s fairly confident in their musical knowledge and taste. We all listen to old records and lean on that. When Lana comes in and says, “No, I don’t like that. That’s horrible. That sucks,” it takes a bit of getting used to. But, in the end, all credit to Lana; she knew what she wanted. All of us essentially had to change our styles to fit hers. There were moments when Lana was straight-up crying, because the fight between what the music should sound like was super intense. She had this very specific idea, and Dan had this very specific idea. But it met in the middle, which is why that record is so cool.

Why go to somebody like Dan, knowing everything he does has an aesthetic, if you’re not looking for that specifically?

She was scared, because it was her second record. She had the SNL debacle and Pitchfork panned her first record. She had a lot of success, but she also had a lot to prove. What she was doing with us was a pretty big chance, at the time. Maybe that has something to do with it.

Sometimes the result is magical, because you’ve got two competing personalities and ideas that end up creating something pretty special.

Yeah. That was definitely the case. The entire record, she kept on saying, “I hate funk. I hate groove. I hate soul. I want it to sound like The Doors or Nirvana.” On the session, it was me, Nick Movshon on bass, and Max Weissenfeldt from The Poets of Rhythm, who’s the funkiest drummer who’s ever lived. She had a room full of groove and funk musicians that she was fighting against the whole time, but that’s probably why the record’s so cool. We were trying to play differently, but she also had to conform to what we were doing.

How did working with The Carters – Jay-Z and Beyonce – happen?

It ties into the new record a bit. When I moved upstate, I was like, “I’m leaving all my friends, and I’m going to go upstate. I’m going to be by myself. I’ve been living in the city for 20-some years. I go to the studio every day and see my friends and make music with other people.” Now I was going to go upstate and be by myself. I was like, “Well, one thing that I want to do is make samples for producers.” So, I learned how to use Ableton [Live] and I would make these songs, but like loops. I sent that out to a bunch of producers. One of the producers was Cool & Dre [Marcello Antonio Valenzano and Andre Christopher Lyon], and they picked that song. It was a sample called “Zudan.” They used that sample and created the song [“Summer”] for Beyoncé and Jay-Z. The way that it ties into the new record is that I had been making these samples, and I loved the way they sounded. They were these orchestral pieces of music with very little drums, because trap producers don’t want drums for samples. I wanted to do this style of music for myself. But, anyway, these guys Cool & Dre, they took the sample, took the whole song, and then gave it to Beyoncé. They added some cool strings and stuff. But I’ve never met Beyoncé. I didn’t even know it was Beyoncé until maybe three days before the record came out, because they wouldn’t tell me who it was for.

I wanted to talk about your work with the Wu-Tang Clan.

Yeah. When I got the Tascam 388 and started recording my own music, in a year or two it became [El Michels Affair’s] Sounding Out the City. That got into the hands of a friend of mine who works for Scion/Toyota, the car company. They were doing these events with a band and an emcee; this whole concert performance series. They’d do Big Daddy Kane with a live band, or Jeru the Damaja and a live band. My record got into the hands of one of those people, and they paired us with Raekwon. We did a concert in the city, and to this day it’s probably the best concert I’ve ever played. It was so much fun. A tiny little club in New York, Raekwon and El Michels Affair, playing all the Wu-Tang shit live for the very first time. It was fucking nuts. The crowd was going crazy. It snowballed. The music sounded cool as instrumentals when we were rehearsing. So, we put out a 45 of “C.R.E.A.M.”, and it sold more copies than anything we’ve ever done combined. We thought, “Okay, it’s time to do a full-length of this, because people like it.” And that was it [Enter The 37th Chamber]. It started getting bigger and bigger. More members of the Wu-Tang Clan would join in, so at a certain point we would play these live shows with seven members of the Wu-Tang Clan.

A few years ago you made the El Michels Affair record Adult Themes.

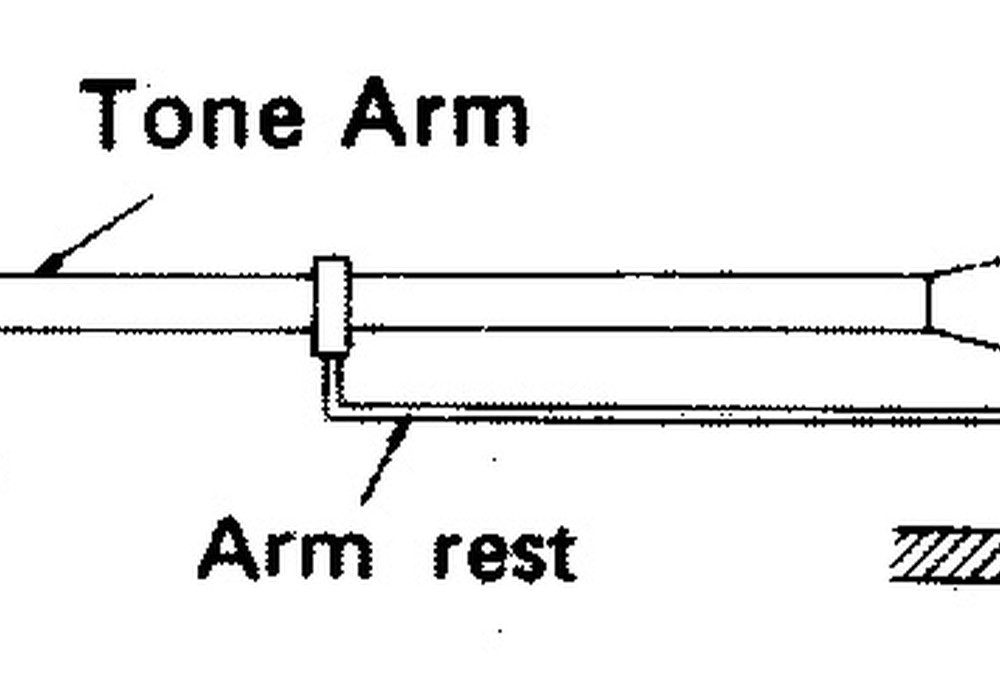

The reason I even made this record was because of a friend of mine, Eothen Alapatt. He runs Now-Again Records and manages Madlib. I went to his office, and he has this crazy hi-fi setup. He’s that guy who has the special mono needle; the Thorens turntable that only plays mono records. To show off the setup, he played this soundtrack record by this guy, François de Roubaix; this French dude who made incredibly sophisticated soundtracks for these French slasher films. He played me this soundtrack called Daughters of Darkness. I had a bit of a religious experience when I was listening to it, and it might have been because he had this whole hi-fi system. I don’t have a hi-fi system – it’s too expensive. But when you hear music on those systems, it’s totally insane. I was listening to this record, and the shit was 360 degrees. You’re in the room with the orchestra. I was like, “All right, I want to make a record like that, because this was incredible.”

Was your record tracked live? At times, it’s fairly elaborate-sounding, even though it has a very vintage vibe.

Most of the time it’d be probably four people in the room at once. All of the rest was overdubs. It’d be drums, bass, keyboard, and acoustic guitar. Those were the live ones. Two songs on the record that were recorded, even before Adult Themes was a concept. “Hipps” and “Life of Pablo” were recorded four years ago. That was me and Homer messing around. We put one ribbon mic in the middle of the room and recorded five or six songs. Two of them made the record four years later.

Is that how a lot of this is recorded?

When I’m in charge, yeah; because I’m lazy. There are a couple songs like that. But the engineer I work with all the time, Jens Jungkurth, is a mad scientist. So, there will be situations, like that song “Enfant;” that’s five mics on drums. Whenever we track and bounce it to Pro Tools, it always goes down to one or two. Even if there are five mics on the drums, they’ll get summed and go to one or two tracks. Because five mics on the drums, once I get it in Pro Tools, it’s going to take me forever to figure out what I like. I’d rather have no options than five options.

That takes guts to put a track on a record that was recorded with one mic.

To me, at least, there are two paths for drums: You’re either going to get a clean sound, or an interesting sound. It’s much easier to get an interesting sound with one or two mics.

To me, it’s a good-sounding drum kit, in a good-sounding room, with a good player.

Absolutely. I was doing this project that was slightly reggae. The reggae I like is all the Lee Perry [Tape Op #136] and early ‘70s, like Scientist [#136]. I put the drums through a phaser, but just for the electronics and maybe a little bit of phase. When I ran it back, I kept the old drums in by mistake. They were completely out of phase, and it sounded exactly like the record I was trying to make it sound like. Back in the day, reggae was out of phase constantly.

I interviewed Lee Perry and Scientist, and I spent some time with Lee Perry.

He’s the greatest producer of all time. It’s all instinct, right?

Oh, yeah.

There’s nothing to it. He had shitty equipment but an amazing ear, and he didn’t give a fuck.

Are you scoring your songs out and giving people lead sheets, or is it all, “Let me show you the tune”?

It’s like, “Let me show you this music I’ve been listening to. Now let’s do something like it.” About 90 percent of the music I make starts like that. “Oh, I like how this record sits. I want to do something like this.”

I read that Adult Themes was the score to an “imaginary movie.” Is it helpful for you to imagine scenes as you’re scoring, or are you scoring and then imagining scenes?

I’d been listening to a bunch of soundtracks. I liked the fact that they were these unconventional song forms. Some of them had very little melody, and some are mood pieces that were obviously meant to go along with some visual.

Right. Let’s jump in and talk about some of the tracks on the record. I have several favorites. Let’s start with “Villa.”

The very first day we recorded we did five songs we made up on the spot, and one of them was “Villa.” That one sat for a long time before I figured out what to do with it. François de Roubaix has this one song, “Dernier Domicile Connu.” It’s been sampled 25 times by Missy Elliott, Lana Del Rey, and Kid Cudi. It starts with this percussion loop that he made, and then it has this cello bit that people love to sample. At the beginning of the song I wanted to do something like that with a weird percussion loop. I did that on Ableton. That was one of the last songs to come together, because I couldn’t figure that one out for a while. I love Ableton as a program. It’s like playing video games. It’s essentially these blocks. What you see is not really music. You know how if you play Tetris too long, you go to sleep and keep playing Tetris in your head? That’s how I’d get with Ableton. I’d be cutting and pasting blocks of music in my dreams.

To have this esoteric French B-movie film score showing up in American hip-hop, how do you think that happens?

I know. The hip-hop producers I know from that era have the craziest knowledge of American music. It’s insane. I met Pete Rock once. I was in this room with him, Madlib, and a couple of other people. Pete Rock knew more than anybody else in the room. If you played him any record, he knew it, knew the label it was on, and knew the producer. All those guys were digging for records. And then, when they found records, they’d read everything about it. If they liked the arranger on a Curtis Mayfield record, they went and found the arranger’s other records.