In Tape Op #55 we had a wonderful chat with John Cuniberti, where we discussed everything from his ReAmp product to recording the Dead Kennedys and Joe Satriani. In this interview we asked him about his OneMic series, where, for several years, he’s recorded artists performing two songs live in a room, captured via one AEA R88 stereo ribbon microphone. These recordings are also shot for video and are stunningly beautiful. We were curious about the process, so I got John into Jackpot! Recording a few years back for an interview, while he was at The Hallowed Halls studio nearby tracking some OneMic sessions.

How did this series begin?

Let me ask you this. I've asked other engineers this question, and I already know what your answer's going to be. What's the best part of a recording project?

The basics. And a great vocal take.

Thank you. Right! That's exactly what I do. That's all I do. You can see where I'm headed with this. As a recording engineer, I've distilled it down to the good parts. None of the tedium of mixing or the tedium of those horrid days and nights of overdubs. I've eliminated all the parts I hate and distilled it down to the one thing I enjoy more than anything.

What were the early sessions like?

The first batch of OneMic that I did was in the Bay Area in studios that I was familiar with that have nice acoustics and controlled environments. I was working with bands I knew and were friends. I knew if the whole thing blew up in my face, I could probably buy them off with a pizza. As the successes of them came, and the artist response to them was so positive, I decided to start to stick my neck out and try doing it in different rooms. I came up here to Portland to Hallowed Halls in January 2017, and I did another three acts.

I just saw some of those. I could obviously tell it was Hallowed Halls, with the backdrop and the windows.

Yeah. That was challenging, because the room is very live. Needless to say, the room will really imprint itself in this process. But it turned out well; it's very atmospheric. The performers were stellar. They all showed up – like most of them do – willing and ready. No attitude, very casual. I try to find alternative acts that don't have managers and don't have record labels that get in the way and interfere. Part of the goal for me has always been to try to eliminate as much as I can between the artist and the listener, including the engineer. And that would be me!

Taking yourself out of the equation?

I set up a mic and I print it to Pro Tools through the Millennia HV3c [preamp], and that's about as much engineering as I do, with the exception of mastering later. Sometimes the mastering is pretty heavy-handed, because I'm problem solving at the mastering stage. In multitrack sessions those problems are cured during the recording stage, because I’m multi-mic'ing. Certainly, I can fix it in the mix – I don't get to do that here. I don't think I could do this if I didn't have 20 years of mastering experience.

Do you add reverb at that stage?

Yes, sometimes. A lot of the vocals need reverb. I can automate a reverb. When the singer's up on the mic singing, I can gently bring it up to add that. Then, when they're off the mic and not singing, and it's the band in the room with a solo or something, I can back it down and almost turn it off. I always put some mid/side filter after the send, before the reverb, so that I can force more mid, and no sides at all – if I can get away with it – into the reverb. Because the width of the recordings are pretty wide, and when I turn down the side I get a lot of just lead vocal.

You're using the AEA R88 stereo ribbon mic, which is a fixed Blumlein pair, right?

Correct.

You're making sure that you place the vocal in the center of the stereo image, on one side of the mic?

Yes. They have to sing dead center of the two ribbon elements. They can't move their head side to side too much. I had a singer at Sun Studio in Memphis who continually would sing a line, and before the line was done – before the chord change, he would turn his head and look at the neck of his guitar. If you have headphones on, you'll hear the voice sweep to one side. I went out and told him two or three times, “Hey, you can't do that.” He goes, “Okay, no problem. I won't.” Then he gets into the song, he gets emotional… which is great, which I would encourage.

It's such a habit for a singer/guitarist to look over at the guitar neck.

In a typical studio setting, if he's making a recording and doing his lead vocal, he's not playing guitar. He's probably just singing directly into a mic. If this was a mono recording, then the level would come up and down a little bit as he turned his head, but, since this is stereo, it sweeps [across the speakers]. If they're back a ways – some of these singers have such strong, powerful voices that I can get them two or three feet back – then the movement of the head isn't so critical.

What made you pick the R88? Did you try different mics?

I'd owned an R84 for quite a while. I thought, “If I get the R88, I can record stereo,” as people would do with a room mic or a drum overhead. Then I got the idea of trying to record an entire band around the microphone. My reasons for doing it were partly because I was bored. I'm in my 60s, and I've made a lot of records in conventional ways. I thought, “What else can I do that would bring the excitement back to recording for me?” I've spent thousands of hours in control rooms doing overdubs and working on records from the ground up, one track at a time. I started with analog, and, of course, when digital came along I jumped on board and ended up with 60 tracks. It got tedious. The other thing was that there's a safety net that was created by digital. It's great if you want to make perfect records, and I've made a few. It's a perfectly legitimate process. But I was never worried, scared, or concerned at sessions like I used to be when I was cutting to analog, where I had to sit with an auto-locator in between my knees, punching in and out Joe Satriani guitar solos all afternoon.

I imagine. He's a meticulous musician.

Yeah. There was an element of fear instilled in me then. There was the reward for taking that risk, jumping in, working that hard, and then hearing the results and being proud of it. But, as digital came along, we created more and more safety nets – multi-mic'ing guitar cabinets because we can't make a decision, doing endless overdubs. I got to the point where, “Yeah, I can make great-sounding records, but the thrill is gone.” I grew up and started in live sound. I missed the buzz of getting out there on the stage, getting those mics up, and getting the band out there. They're going to play the song once in front of all of those people. You've got to get back to front-of-house, and you've got to push those faders up. My heart would pound. If it was great, I could feel great about it. If it was a disaster, then I would learn from mistakes and get better. I started thinking, “What can I do that nobody else is doing to give me that thrill again?” I decided that I would try to record an entire band around one microphone. I don't mean one bluegrass group; I mean electric guitars, electric bass, acoustic drums, and all the singers. How do you do that? When I was fooling around with the R88, I realized that there are two stereo fields – front and back. With condenser mics, like an [AKG] C24, one side of the capsule always sounds better than the other side. But the inherent nature of a ribbon is that both sides sound the same.

They're technically the same element.

Yes. I have a 90 degree arc in the front of the microphone to set the band up in front of, but I also have a 90 degree arc in the back of the microphone to elaborate on. I can put singers on one side, or the drums on one side and the guitar amplifiers on the other, and I can arrange these around. I have 180 degrees to work with via two 90 degree zones. Then the 90 degrees on the sides of the microphone are dead zones. You can't put anything there. I pulled out a piece of paper one day and I thought, “If I was going to do this, how would I do it? I'd put the drums here, so I'll get a nice stereo image. But, wait a minute; I can't have it close. I better pull it back. Then I can put a bass there, but how do I get the bass in front of the drums?” I went around a bunch of different scenarios and permutations of, “How do I make it sound like a multitrack record?” The idea wasn't to record a band with a stereo microphone in the room. We've all done that. It's always muddy and something's missing. It certainly doesn't sound like a record. I thought, “Can I make it sound like a multitrack recording? Can I fool people?” That was part of the impetus to have the video; one camera and one continuous take. That proves that you're not seeing any other microphones. If you look at the drum kit, there are no microphones on it. It's not a perfect recording. None of the recordings – with the exception of maybe three that I'm very proud of – can rival a really well-done multitrack recording. Can it rival records from the '60s? Absolutely. Can it rival records from the '50s? Absolutely. Can it rival the sound of records from the '70s? In many cases, they do. There are a couple of pieces I've done where I think that they're some of my best recordings. I'll compare them against anything I've done on multitrack.

Which ones do you think came out the best at this point?

Technically and performance-wise, The Imaginaries "Thinking 'Bout You, "San Geronimo & Friends' "Masters of War" and Jackie Greene's “Gone Wanderin’.” There’s a lot of hard work that gets put into these, but there's also a lot of alchemy. There's a lot of throwing of the dice. Studios like Muscle Shoals and Sun Studios; these places are museums. They haven't been touched, changed, modified, or made modern by any stretch of the imagination. The control rooms are not to today's standards. The monitoring in both those rooms was highly compromised. I don't really know what I'm getting when I'm sitting there in the heat of the moment. I've got a band out there who's anxious about the whole process. They've done three or four takes, and I'm looking for the best take. I will always take a best take over a best recording. I owe it to them, because they're taking a leap.

Are you leaving the artists to the arrangements they walk in the door with?

Yeah. I ask them to send me the songs in advance, or I'll listen to their records and pick songs that are appropriate for this process. If it's full-on heavy rock, where the drummer's pounding hard, I'll probably avoid that song.

It'd be difficult to do a metal band, to get the balance between the vocal and the loudness of the amps and drums.

The first batch of recordings I did were subdued, quieter material that lent itself to the process. My first day at Muscle Shoals, working with this band called The Dozens, they came in with a B3, electric piano, two guitars – with one playing bottleneck, a female singer, and a drummer with a full drum kit. When they started playing at what would be considered rehearsal level, I walked into the room and said, “You're going to have to turn way down.”

To be able to get the vocal above the band.

For guitar players playing through amps, even though they're playing through pedals, I warn them in advance, “If you're going to use distortion, don't expect to get it from driving that speaker. Don't bring a [Fender] Twin Reverb in here.”

“Don’t dime it!”

Exactly. It wouldn't be the first time where I had a band well-balanced doing two or three takes, and then somebody decides they want to be louder because they can't hear themselves. They forget where we are and what we're doing. Bass players, particularly. They'll start playing again, and I'll have to stop. I'll run out into the studio and go, “What just happened?” It's that sensitive. Being a recording engineer, I've become sensitive toward acoustics. When I walk into a room, I hear its personality almost immediately, and inherently I know where I want to put the drums. Other people don't get it. The room becomes paramount in the sound.

I saw in a couple of videos that people were using headphones for singing.

My instincts would tell me that wearing headphones would be the thing to do. They’re essentially hearing the final mix in the headphones. Wouldn't you want that, and to play to that? Once I get the whole balance with the singers in there, oftentimes they go, “I like the way it sounds. I don't need headphones.” The bass player and guitar player love the fact that, even though they might be sitting next to the drums, the guy isn't beating the living hell out of them. I'm not saying they refuse to wear headphones, but I give them the option. I even recommend it. They go, “No!” Maybe half the people wear headphones and half don't.

Have there been sessions that didn't work out?

Yes. For a number of different reasons. Sometimes I get them around the mic, we start working, and within an hour I know it's utter failure. Mostly it's because what they're trying to do in that room doesn't work. It has to be copacetic. There has to be a marriage of the music and the arrangements in the room. The room acoustics are everything. I had one act come in and they had a lot of acoustic instruments. They're definitely the hardest to deal with. You would think it’s the opposite. If you look at the Grand Ole Opry, they have one RCA 44 mic with five guys around it and it sounds great. But when you try to do this in stereo, in a room that is cranky or ornery and not complimentary, it's a disaster. The double bass boomed. I couldn't control it. Another time we had a camera failure. Now I always bring two cameras, and I always bring two R88 mics.

You had to buy another mic?

AEA has been kind enough to ship them to wherever I'm recording as a spare. Obviously, they're benefitting greatly from these recordings. I can't think of a better way to showcase what these microphones can do. Early on, I tried a OneMic with an AKG C24 [tube condenser mic]. It was an absolute failure.

What do you feel the main difference was?

It was bright and unnatural sounding. Those mics are made to boost the top for analog recordings; particularly for distance, like orchestras. When you record them digitally they're often too bright. I don't need out of control EQ. Ribbon mics take EQ quite well. I’ll put on a 2 dB EQ shelf, starting at 2 kHz, and it opens the mic up. It's absolutely gorgeous.

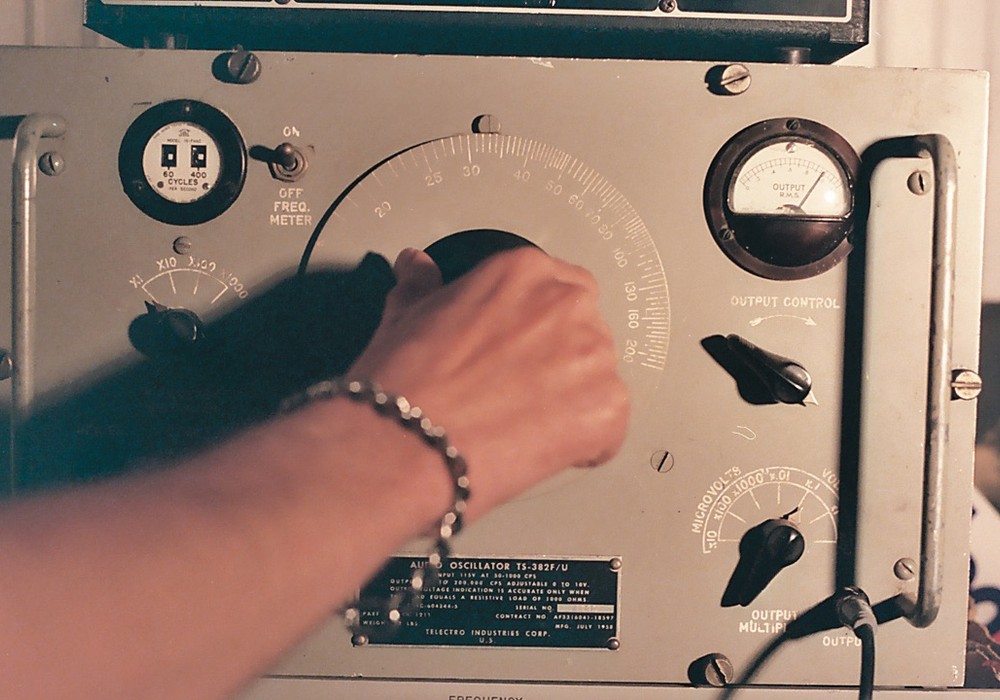

What’s the signal chain?

It's the R88 to the Millennia Media HV3c [preamp]. I like the Millennia because it has detents. When you're recording with a stereo microphone, you need to know that the gain is absolutely equal on both channels. I don't want a preamp with variable knobs; I want one with click stops. I have the ribbon mod that they do, an extra gain boost, which I haven't used. Bands usually play loud enough so I don't need that extra boost.

That's a good clean preamp.

It is. Not only is the preamp clean, with low distortion, lots of headroom, and high bandwidth, but it's a pleasant-sounding preamplifier. That's important, because it's all that's between us and the musicians, besides the microphone. It works well with this ribbon mic.

Do you bring your own A-to-D converters, or do you use whatever studios have?

I have been using what’s at the studio, but fortunately I've been treated to all high-end gear.

How does the filming integrate with the sessions?

My cinematographer, Nathaniel Kohfield, gets the music in advance. He's a musician, so he learns the songs and arrangements. He’ll know that after the first chorus that they're going to do a guitar break and he needs to get over to that guitar. He does a ballet around the players. The very first OneMic I did, I said, “I gotta film this. No one is going to believe it sounds this good.” I went out into the studio and walked around with my iPhone to prove that I did this with one mic. When I decided to do it more seriously, I thought, “I need to get a person who's a musician who can follow the arrangements, work with a Steadicam, and do one continuous shot.” It has to be one continuous shot. I know that if people see me cutting with a three-camera shoot – you're on the guitar and it immediately cuts to the lead singer – they're going to instantly think, “Oh, there's editing involved! If he's editing the video, he's probably editing the audio.” Once I see the music sync’d to the video, I immediately want to make changes. It's funny how the visual affects what you hear. It's a phenomenon I wasn't privy to until I started the process. When I tell you my signal path, you'll see how I'm able to manipulate the sound to some degree. I use a NUGEN Monofilter [plug-in], which allows me to turn the signal into mono, at whatever frequency I want. Obviously, the low end, the bass – the kick drum, the bass guitar – I want in the center. I will use the Monofilter set around 100 Hz, and then gradually I'll force it to mono. By the time it's down to 50 or 40 hertz, depending, it's all mono.

Like cutting for vinyl.

I think that's what this plug-in was designed for. That's essentially what the electronic lathes would do, to force it to mono at frequencies below 100, because you definitely don't want stereo bass when you're trying to cut a lacquer. Then I go to a multiband EQ; FabFilter Pro-Q 3. I can select the frequency, select a Q [width], and then select a threshold for whatever amount of limiting or compression I want to apply there. That is essential for this process, because if there's something that gets a little bit too out of balance, I can go in and find out where those notes are. If the A-string on the bass blooms in the room, I can add a little bit of limiting to that note, adjust the Q, center it, and push that note enough down to where I need it for a guitar solo. If it's reacting to something I don't want it to react to, I'll automate that band to switch on and off where I need it. That will massage the mix and keep parts a little more in control. I will then go to some form of compression. I like the UAD Fairchild 670 [plug-in], because it has a sidechain now. I can have it pull back only 2 or 3 dB, like you would a vocal. I can use the sidechain so it's only affecting sound from 500 or 300 Hz and up. If the lead vocals are starting to push too far out, that will settle the lead vocal down into the mix. Then I'll go to the UAD 4000 G Bus compressor. I use that to glue the mix together in the traditional way. I do a very, very slow attack and Auto release, and I only let it come back a couple of dB. That gets the rest of the mix glued a little bit more together. From there I'll go to the UAD Precision Limiter, which is their brickwall limiter. It's the best there is, as far as transparency. I'll do 2 or 3 dB of that. Because this is for video, I don't have to have a loud final master. Plus, YouTube would throttle it back anyway. I can crush it, but they're going to turn it down. I bring it up to a point where it's starting to compromise the sound, and then I back it off a couple of dBs. That's basically my signal path and how I manage it. My experience as a mastering engineer has shown me the way to utilize some of these tools to make repairs in post-production.

How do you pick the artists?

I only bring in acts that perform live, and I insist that they send videos of them performing live. I certainly wouldn't trust any studio recording they sent me. Who knows how long they've spent on that? A lot of bands, no fault of their own, spend a lot of time at home recording and very little time on the stage. When the artists agree to do this, and they all come in and we're going to record organically around the one microphone, it takes some time for them to get used to this idea. I warn people ahead of time, “I can't guarantee you results with this.” I never know. There's such an alchemy between the artist, their instrument, the amplification, the song arrangements, and all the idiosyncrasies of the room. There's a certain amount of angst, anxiety, and tension in these sessions. When there's a multitrack session, there's less of that. Everyone has to rise to the occasion. I've taken away the safety net, but I'm giving them back the power to show their music. It's been hugely rewarding for me. I always tell the bands, “After people watch these videos, I can absolutely assure you that they will not be disappointed when they come to see you live.” Because what you see is what you get. There's this feeling in the room when we know we got the right take. I can sense it and the band can usually sense it. Of course, I will continue to make multitrack recordings. I'm not saying this is the only way to do it.