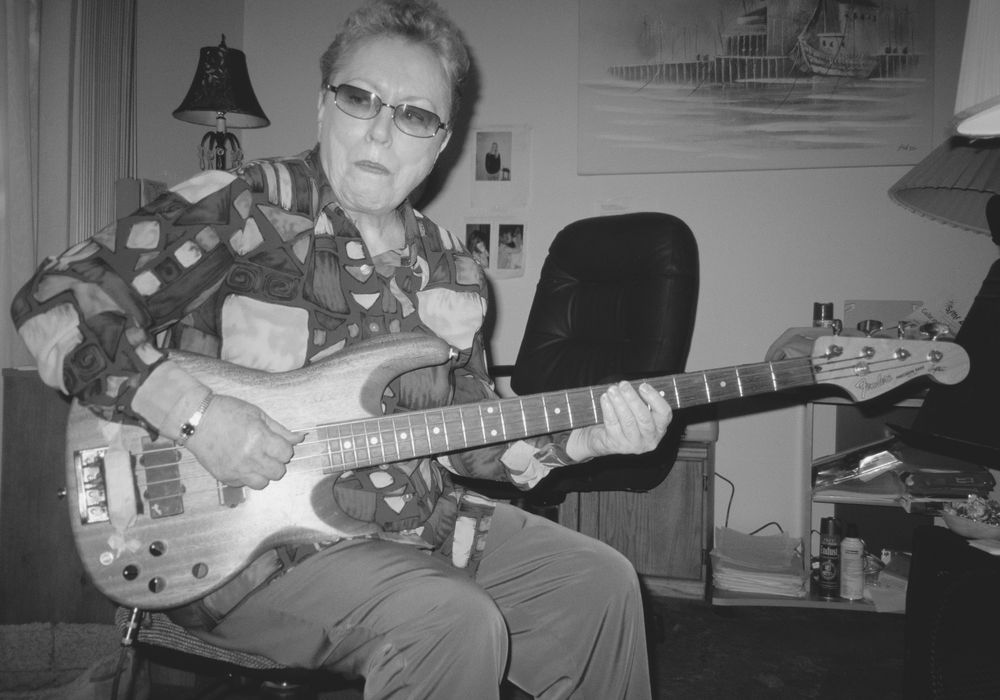

A multi-instrumentalist, performance artist, educator, programmer, and author, Sandy Stone’s lived a full enough life to fill several books. With a list of credits that includes Jimi Hendrix, Van Morrison, Crosby & Stills, Mississippi John Hurt, Marty Balin, and The Byrds, Sandy’s portfolio is that of an engineering titan. Becoming the house engineer for Olivia Records in 1974 should be an achievement in itself, yet her name is rarely invoked alongside those of her recording peers. Her obscurity is partially because her later, and very important, work in academia eclipses that of her earlier career. Sandy is transgender, and noted as a founder of the academic discipline of transgender studies. She began her career in the early ‘50s, scoring and engineering movie soundtracks while still in high school.

“The first thing I remember recording, that wasn’t content I generated, was The Steve Allen Show [off the] television. I had built a recorder with a vacuum cleaner motor for the capstan. I had to file it down, because it was the wrong size and a little egg-shaped. Plus, I think the shaft was magnetized. [laughs] After that I started recording loops. That would’ve been around 1954. There were a lot of junkyards. I learned how to break in, so I had a large supply of random junk to build things out of. A lot of it was fumbling around in the dark until it either worked or I gave up.”

Graduating at 16, she audited classes at universities across the East Coast, and landed jobs at Bell Labs and the National Institutes of Health before pursuing work as an audio engineer. Early on, Sandy recorded Mississippi John Hurt’s Folk Songs and Blues in 1963 in her log cabin studio.

“He [musicologist Richard ‘Dick’ Spottswood] contacted me through an intermediary. What may have attracted him was that I didn’t have a traditional recording studio: I had a log cabin with tape recorders in the bedroom. My bedroom was set up as a control room and microphones in the living room. Dick and John moved in for three days, and we did something like 30 reels. I learned what to do if you’re trying to play and have arthritis. What John did was immerse his fingers in whiskey glasses full of kerosene and rock salt. He’d learned that from his grandma. That was life for three days; eating, sleeping, and recording. The noises of my home were going on in the background, including a little cuckoo clock that I forgot to turn off for the first few takes. I used a Capps CM2030 [microphone]. It was very carefully placed. I have to add one thing: Capps did not build their microphones to be put on microphone stands. They were built to be hung. Getting a mic near John was a very tricky proposition, involving gaffer tape and all sorts of other stuff. [laughs]”

Stone’s career began to take off upon being hired at The Record Plant in NYC. Her job interview to become a maintenance person? They had a broken reel-to-reel and asked if she could repair it

“It was a Scully 12-track. It had Lipps heads, that Fred Lipps had made, because there weren’t any 12-track heads around. I did get it to run, they hired me, and I lived in the basement. I slept on a pile of Jimi [Hendrix’s] capes. He was keeping all his tour equipment down there, because The Record Plant had this enormous basement with a large freight elevator. After I finished up in the studio, I would get on the freight elevator and go down and sleep on Jimi’s capes. Then I would get up in the morning, use the bathroom to get washed, and go back and do whatever I was doing in the studio. Tony Bongiovi [Tape Op #127] was working with Jimi at that time, and occasionally Gary [Kellgren, co-owner of The Record Plant]. I was, as usual, behind him [Tony Bongiovi] watching. At one point he turned around to me and said, ‘I’m feeling sick, kid. I don’t wanna finish this date. You take over.’ He got up and left, and I sat down at the board. I had fantasies of lightning coming out of my head and St. Elmo’s fire coming out of my fingertips. It was a completely unexpected, stunning, moment. The odd thing was, Jimi loved what I was doing. He asked if I could go on doing it. And Gary, having his own fish to fry, said, ‘Sure.’ Every night Jimi would come in, we’d lay down something, and then he’d put on overdubs. And overdubs, and overdubs, and overdubs. Eventually, Noel [Redding, bass] and Mitch [Mitchell, drums] would get bored out of their minds and quietly sneak out to The Scene, which was a private club for musicians. A couple of hours would go by, Jimi would be ready for an overdub with drums and bass, and Noel and Mitch would be gone. Jimi...