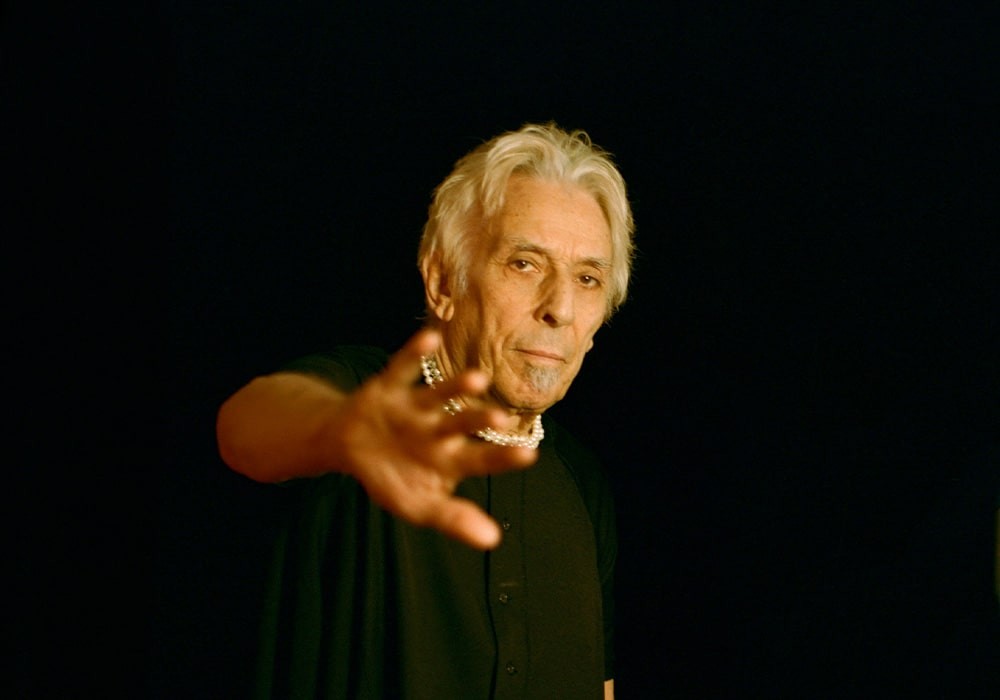

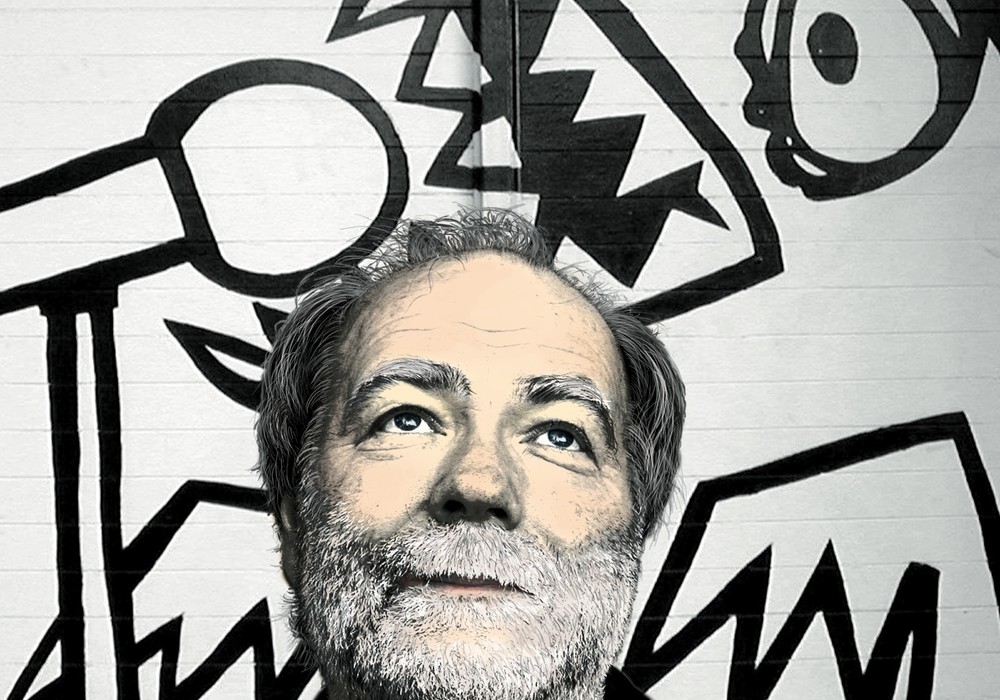

Blak Emoji is the project/band of producer, songwriter, and multi-instrumentalist Kelsey Warren. His recently released third album, Eclectro, is a fun and inventive listen, so I dropped him a line and we got down to chatting about how it was made.

I went back and listened to some previous Blak Emoji records, and this one has a little more depth to it. There’s more going on sonically.

I’d agree. I had more time.

Didn’t we all?

Yeah. That was it for me. I was already on the road to recording and working on ideas for new songs. I would sit and work on sounds for hours. The pandemic forced me to throw myself into this without interruption. It’s not a popular thing to say, but last year [2020] was a good year for me. I didn’t have anything else to do but music. I was on tour, and I came back here. I remember hearing, “You’ve gotta get back home! Everything’s going to stop!” And that was it. My production jobs were gone. My gigs were gone. What keeps me the most sane is making music and recording. I had more than enough time to marinate on songs and try different ideas. There are 12 songs on the album, 13 on Bandcamp, and maybe seven or eight of them were constantly on the list. The other four or five I changed so many times. I thought, “I’m pulling this off.” I had time to do it and not stress about having to tour or do anything else.

When you were working on the album order, was it more about the flow and seeing what fit together?

Yeah. There are probably 30 songs I recorded. There are some that feel like “singles,” but there’s a theme. I like albums. I love [Prince’s] Purple Rain, [Nine Inch Nails’] The Fragile, or [Pink Floyd’s] The Wall. All of those records have a common thread and a common sound, but many songs are different. It’s a roller coaster ride. That’s what I was trying to accomplish with Eclectro. I wanted a consistent theme and sound, but it’s still all over the place. There are a lot of different styles in there.

I was thinking of it as “future R&B.”

I like that.

I feel the focus is on the songs. The electronics are fantastic, but the songs are what we come to listen to.

Thank you. That’s what I was trying to go for. The album is called Eclectro because it’s an electronic base, but I feel that sometimes people pigeonhole electronic music. Either it’s EDM or Aphex Twin. There’s a song called “Every Mother’s Son.” I was asking someone, “Why aren’t there any protest songs in the genre of electronic music?” A protest song is a guy or girl with an acoustic guitar or it’s hip-hop. Electronic music is so vast. It’s Aphex Twin, but it’s also Kraftwerk. It’s Prince. It’s Nine Inch Nails. It’s Eartheater. All of those sound different. Prince and Nine Inch Nails are perfect for mixing sonics with songs. I love The Beatles as much as I love Ministry. Why not mix it up, if it can work? I’m not trying to reinvent the wheel. I’m trying to make songs that I want to hear.

That makes sense. It looks as if you’re at your home studio right now. What’s the place you did this in?

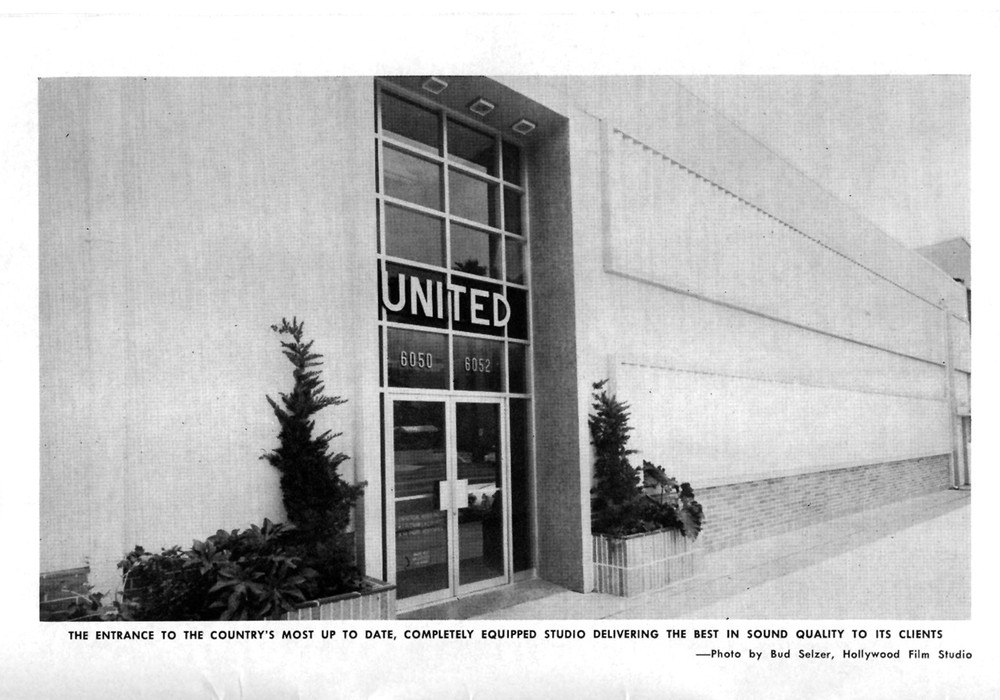

Here, in my little bedroom. Nothing fancy. I also started producing a little bit more for other artists, because I had the time. I’ve done that in the past, but I always wanted to do more. I couldn’t go to a studio. A lot of the people I’m working with, it’s a different thing. “Okay, let’s do something. Do you have something to record your vocals with that’ll sound clear that I can take and do something with?” It’s a whole different environment. With my previous record, Kumi, that was a mixture of my bedroom and a studio I went to in Brooklyn called Rift Studios. Good sounds, and great engineers. I’ll go there when a song needs big drums. I can’t do that here. Sometimes, I want that studio sound. Other times it’s, “Oh, whatever.” Here I worked at my own pace. Some songs came out in a day. Some came out in two. “Float” took a year. There’s no pressure from the other outside work. I don’t have a manager, and I...