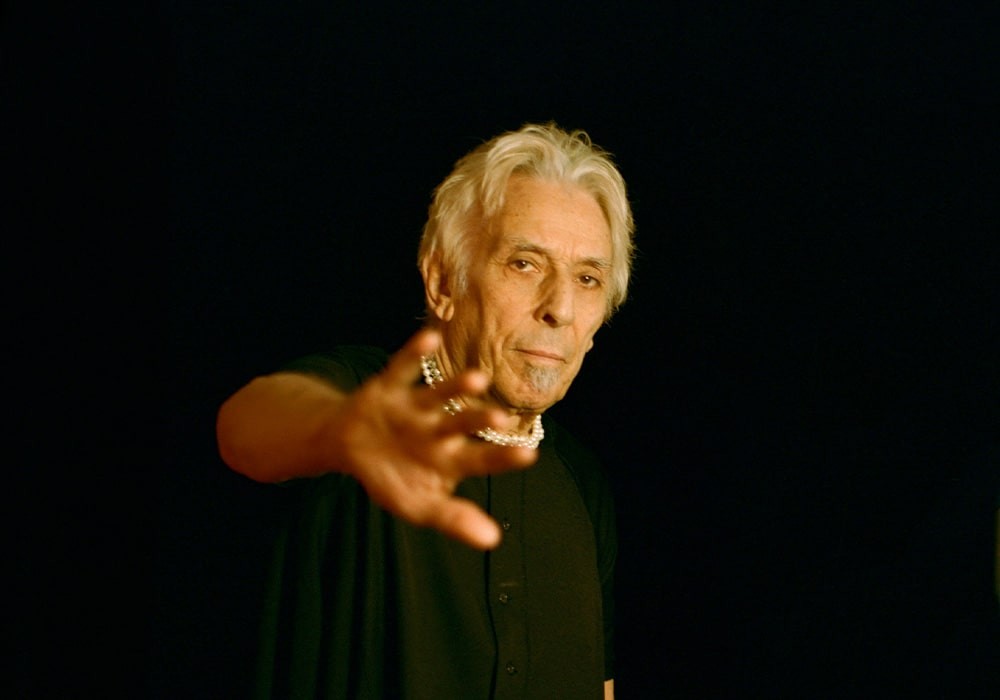

My good friend, engineer/producer and occasional Tape Op contributor Robert Cheek, turned me on to the group Loma. Their music didn't grab me initially, but a few months later I went back to their most recent LP, Don't Shy Away (Sub Pop Records) and it quickly sucked me into its sonic world. I'm now totally obsessed with the band, and that album in particular. As I was poking around trying to find more information, I realized that one of the three principal members of Loma, Jonathan Meiburg, has written occasionally for Tape Op (he most recently interviewed Danny Reisch in Tape Op #146). Small world indeed! Besides Jonathan, Loma consists of Dan Duszynski and Emily Cross. Dan has also written for Tape Op (most recently Caribou in #105), and runs Dandy Sounds Studio in Dripping Springs, Texas, outside of Austin, where, besides Loma, he has recorded Molly Burch, Jess Williamson, and Shearwater. Jonathan is the principal member of Shearwater, and met Emily and Dan when their band, Cross Record, opened for a Shearwater tour. All three members contribute musically to Loma, while Emily, who is also a visual artist and death worker (see this issue's cover art), is the main vocalist. A small group of guest musicians add textures such as strings, woodwinds, additional keyboards, drums, and bass. Brian Eno (Tape Op #85) is a fan of the band and co-produced the track "Homing" for Don't Shy Away. Loma is both melodic and noisy, creating grooves that people want to keep listening to. They are both a traditional band while also remaining fairly experimental. I once heard a writer refer to Yankee Hotel Foxtrot-era Wilco as the "American Radiohead." I would also add Loma to that small group, even if two of the three members have moved out of the country since Don't Shy Away was released. Curious to learn more about their process, I chatted on the phone with Jonathan and Dan while they were both in Texas starting work on the next Loma LP. I also dropped a line to Emily to get her thoughts as well.

How did everyone meet and start Loma?

Jonathan Meiburg: I first heard Dan and Emily through the Cross Record album they made called Wabi-Sabi. It's one of those records you get lost in – it's dark and fascinating, full of beautiful sounds and bold choices, and all I knew was that they'd recorded it somewhere in rural Texas. I asked them to open for Shearwater during our tour for Jet Plane and Oxbow, an album we made with Danny Reisch [Tape Op #146] and Brian Reitzell [#107]. That version of Cross Record was just Emily and Dan, so they squeezed into our van for a few months in the U.S. and Europe. I watched them perform every night, and I was always stunned. I was amazed by the sounds they made, the atmosphere they conjured, and the way they seemed like far more than two people. Emily played some guitar but mostly sang, and Dan played drums and baritone guitar – often at the same time – while running effects on Emily's vocals, playing keyboards, triggering loops, and singing backup. I still don't understand how he did all that at once.

Dan Duszynski: Necessity. If I'm mixing everything before it hits the PA, we don't need to take a sound engineer; and no house engineer is going to know where we want weird delay throws anyway. But I only have myself to blame if it sounds bad.

JM: But it never did! I was exhausted after that Shearwater album, with no idea what to do next. One night in Belgium, during Cross Record's set, I thought, "I love this music, and I don't understand it. What would happen if we started a band together?" I asked, and they said, "Yes." Then I booked a ticket to Texas. We figured we'd sort out the details later.

DD: And we're still sorting them out!

JM: Dan, you started off as a drummer?

DD: Guitarist and drummer. But yeah, I played a lot of music as a kid. I started playing in bands and then figuring out how to record the bands.

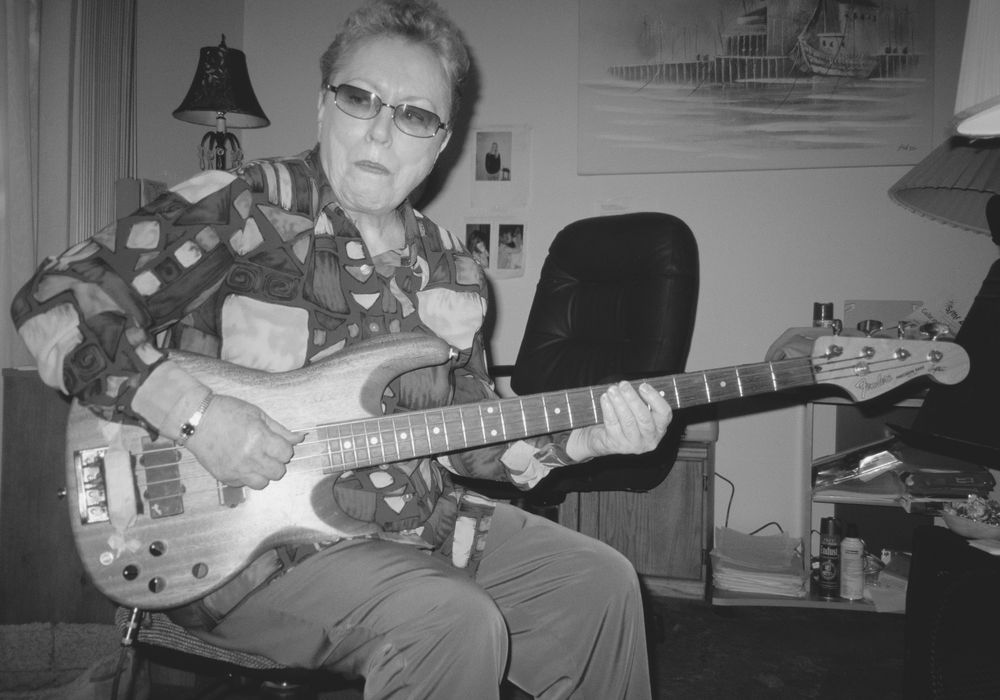

JM: If you keep making music over many years, your abilities grow in funny ways. After two decades, you end up with skills that you never thought you'd need – like business management! But you also pick up new instruments and production techniques, and one thing leads to another. I've been playing bass a lot more in the last two years, even though I'd never call myself a “bass player” – but it's opened my ears up to the vast possibilities of that instrument. I've come to admire great bass players and drummers. Not necessarily for their technical prowess, but for their ability to create a feeling. In Loma that's always what we're looking for – no matter how much we like a part, or a song, or an instrument on its own, we always ask ourselves, "Does this sound make us feel something?"

You're both engineer/producers, right?

JM: Dan's much more of an engineer than me. I still forget where the "record" button is.

DD: In Loma, we're all producers with equal weight. But making records is also what I do for a living, so I'm always mixing other projects or bringing bands in for sessions. Sometimes I'm engineering, and sometimes I'm mixing. I've been interested in the engineering side since I was a kid learning how to record my own music – which I still do under the name Any Kind. I started going to studios with my bands; I would ask lots of questions and learn as much as I could. Sean O'Keefe, the producer who gave Fall Out Boy their start, made some early records with me and he showed me the ropes.

JM: A lot of nudging kick drum hits to the grid?

DD: [laughs] Yeah. Lots of tiny edits and [Antares] Auto-Tuning in pop punk records! It made me pretty handy with that, though I try to do as little of it as I can these days. In Chicago, I ran my studio for a few years out of a building I lived in next to a train station. That's where I met Emily and came into her musical world – which was the exact opposite of what I was doing. We fell in love, got married, and started recording together.

How would you describe her approach?

DD: Emily's a visual artist – she went to the Art Institute of Chicago – so she comes at music more like a painter than a typical musician. At one point, early on, she described a sound she wanted by drawing a bunch of little dots inside a triangle and saying, "Can you make it sound like this?" That kind of thinking changed my creative path. And then one day in 2013 she found a listing on Craigslist for a crazy-looking house in the woods near Austin, and she said, "We should move there." I said, "What?" There hadn't been anyone living in it for a few months when we moved in, so there were scorpions in every nook and cranny of the place. Emily lives in the U.K. now, but I'm still here, nine years later. Although our marriage didn't last, Loma's been a way for our creative partnership – and our friendship – to endure.

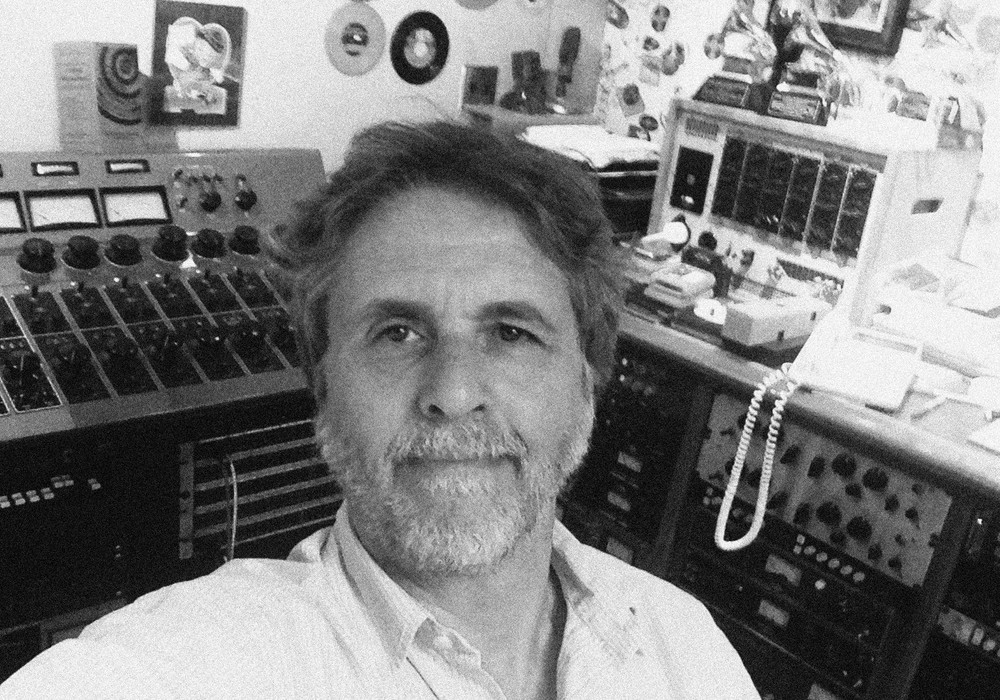

What is the house [Dandy Sounds] like? Did you have to do a lot of work to make it sound good?

JM: It's magical. When I walked in to start the first Loma sessions, my hair stood on end. There's this calm, timeless, slightly eerie feeling in the house that's hard to describe, like it's listening to you. And it's a very unusual structure: It's built out of rammed earth, so the walls are almost three-feet thick. And rammed earth, as it happens, is a beautiful acoustic surface.

DD: Yeah. It's got this unique, reflective, soft property to it that's live, but not harsh. I barely have any treatment up on the walls. The house also happens to be framed out in a mini-amphitheater style, so it's a perfect sonic space. The owners who built it lived in it for a few years, but they didn't realize they'd built a perfect recording studio.

JM: They built it like a tank! The house has concrete floors and outlets all over the place. What's now the control room used to be the master bedroom. There's a hallway running between the control room and the living room/tracking room, which has its own unique, hollow reverb – and there's a back porch that opens onto a huge meadow surrounded by woods. I took all that in, and I was shocked when I saw the recording gear that Dan was using. It was held together with duct tape and glue.

DD: I was still on a Pro Tools 5 system at that point. The old 888 I/O units. My best mic was probably an [Electro-Voice] RE20. And, for the longest time, I held off on doing any upgrades because I liked the limitations. It was like a digital tape machine, in a way. I couldn't use many plug-ins without crashing the system and there was no delay compensation, so I had to do any bussing outside of the box. But at a certain point I realized that if I was going to be mixing other peoples' sessions, I'd need to be on the same technological plane, so I finally gave in and upgraded. But I made a lot of cool records with that older system, including the first Loma album.

On Loma's records the songs settle into these almost trancey grooves. They're pop song length, but I could listen to them for a lot longer than the standard three and a half minutes.

DD: We like to think of the songs as places you'd want to live for a little while.

JM: Miniature landscapes.

Are you both living in Texas now?

DD: I'll probably be here 'til they drag me out, but JM's flown the coop.

JM: Yeah – I've just moved to Hamburg, Germany! But for the last couple of years I lived about thirty yards from Dan's control room, in a well-worn RV from the 1980s he gutted and remodeled. I finished a book in there during the first year of the pandemic, and we made the second Loma album, Don't Shy Away, and the new Shearwater album, The Great Awakening, which comes out in June [2022]. It was a good time to be buried in work.

What's the setup now? Do you have a console?

JM: After the first Loma record, I kept wondering how we could upgrade the studio a bit without spending a ton of money we didn't have. But at that point Shearwater was out of contract, and I crowdfunded a budget for a new album, which exceeded my wildest hopes. I thought, "This is our chance. We can beef up this place, and also make the next Loma record with the new gear."

DD: The most important piece we added was an [Undertone] UnFairchild [Tape Op #133]. I record almost everything through it now, and I sometimes even mix back through it. It's hard to imagine working without it. We also got some great mics – a few older Neumanns, a [Coles] 4038, and several other ribbon mics. "Dark, but clear" is always our goal for Loma albums, and those fit the bill. The best part is not having to mangle the signal to compensate for the iffier bits of the gear I used to rely on. But there's still no console. I've got two of the [Universal Audio] Apollo interfaces, so I use those in console mode and use some of those pres, which sound great. Then I've got a couple of outboard pres. My favorite is a Coil Audio single-channel preamp [CA-286S] that Jim Vollentine built. That goes on a lot of vocals, drums, and acoustic guitars.

But no tape machine? Everything's digital?

DD: Yeah. I never learned to use a proper tape machine, other than my first 4-track – I came up after the era. But now I'm obsessed with all the cassette plug-ins that keep coming out, like Wavesfactory Cassette and [Aberrant DSP] SketchCassette. They all sound different to me, and they're all interesting. I also use the UAD Studer [A800] plug-in a lot. Sometimes there'll be 10-plus instances of it going in a session, as well as on the master [bus].

What's the general writing, recording, production, and mixing process for Loma? Are the two of you are overseeing all of that? Emily's not there right now, I take it?

DD: She's not. She'll be joining us in the spring, when we have a little more for her to chew on.

JM: Emily's a big presence, though. The nice thing about a three-person band is that either everybody agrees, or it's two against one. We make decisions by consensus when we can and majority rule when we can't, so we never end up deadlocked. Occasionally it's contentious, but mostly it's amazingly smooth. We also started this project because we wanted to do things that we wouldn't ordinarily do. We wanted to give ourselves permission to make choices we wouldn't have made in our other bands, and to trust in happy accidents – and when you start with that as your mission, it's thrilling. For example, in the song "I Don't Want Children" on the first album, we recorded Emily's vocal at the wrong sample rate.

DD: We recorded the vocal at 48 khz, but the session was 44.1.

Right!

JM: And when we listened back, we were intrigued. The voice singing sounded like a more weathered version of Emily, and she really identified with it – so we decided, "Okay, this is the Loma voice." On almost all of our recordings, we slow Emily's voice down a little. It's like she's wearing a sonic mask.

DD: Another rule we made was that if my dogs bark or knock something over while we're recording, we have to keep it in.

Do you two work on instrumental ideas together for a certain amount of time, and then Emily comes in?

JM: Dan and I make a lot of sketches that we flesh out or discard later as a group. Sometimes Emily brings in songs, which are often my favorites. Yesterday we were working on a new song she sent us; we kept the first half, ditched the rest, and added a rhythm section that gave it a much heavier feeling. Emily loves it when we jerk the wheel; she's open to very intense collaborations, which is pretty rare among musicians I've met.

DD: She's comfortable just deconstructing whatever. That might be my favorite thing about Loma: We're all songwriters, and we're all control freaks in our own ways, but we respect each other. Whatever we bring to this space, it's understood that anyone is allowed to take it apart and do whatever they want to it if it interests them.

JM: Part of why I wanted to do this in the first place was to be in a band where I wasn't in charge. I'd also never written lyrics and melodies for another person to sing, and I feel my job is to create a character for Emily to inhabit. That character is partly based on my idea of who Emily is, but there's a lot of wiggle room, and we end up creating this hybrid "singer" together. It's fascinating. I've been writing songs for a long time, so the things that thrill me most now are surprises. That song "Thorn," for instance, on Don't Shy Away, is a hodgepodge of ideas from all of us. That vocal ensemble in the intro, that was your idea, right Dan?

DD: Yeah, but it was supposed to go later in the song, and then we moved it to the top.

JM: Then Emily starts talking, which is an excerpt from her podcast What I'm Looking At. Which is exactly what it sounds like: She just describes whatever's in front of her at that moment. She loves it when people think it's boring.

DD: Kind of Andy Warhol-style.

JM: We flew in parts of two episodes: One where she was talking about a mossy log, and another one where she was describing a dried flower. The groove underneath it is me and Dan – I'm playing bass and Dan's playing drums. Emily overdubbed some clarinet, and then our friend and musical comrade, Emily Lee, added that weird, scratchy violin. That one started on a late night, when we were trying make something like [Donovan's] "Hurdy Gurdy Man" – and failed – but we liked the feeling that emerged.

DD: Loma's taught me that the starting point doesn't really matter. If the inspiration is something that we all want to follow, it's going to develop, no matter where we drop in.

JM: For the song "Relay Runner" on the first record, we were watching the Werner Herzog film Bells from the Deep, and there's a scene where two boys from Siberia are singing by a frozen river. One of them is playing a little banjo-like instrument with a snakeskin head, and I started playing two notes in the same rhythm on the piano, which developed into that song.

DD: This way of working takes lot of trial and error. We have tons of songs that we don't finish.

JM: Yeah – there was one I really liked in the Don't Shy Away sessions that was nine minutes long and had all this beautiful orchestral work in it, as well as some stoner-metal drumming. But we just couldn't get it to hang together. Eventually we had to call time.

It sounds like you guys have gotten pretty good at not getting too attached to anything.

DD: Emily's really our secret weapon. Once we start tracking vocals, she'll come in with a machete and make huge changes to the songs. She'll say, "Let's change the key," or, "Let's slow it waaay down," or, " Let's get rid of the main instrument." She sees things we've missed, and we rely on her for that.

JM: Her hit rate really drives me crazy, by the way. She's so good at finding exactly what's wrong with songs that have stumped me and Dan.

Does she ever have issues interpreting the lyrics you wrote?

JM: Usually I'll do a rough guide vocal to give her a melody and approach, and then I'll give her the words. Then she goes in the control room, shuts the door, and does takes by herself for a while. If a line is not working, she'll tell me and I'll try to fix it. Lyrics are always scary because that's where the song becomes itself, and I can feel exposed. But this process forces me to remember that the song is external to me.

DD: Loma's been healthy for breaking down whatever ego I have about ideas I think might work or might not work. I love thinking that I know what's going to happen, or what should happen, and then watching it go in a different direction. When something I was holding on to gets destroyed, the result often becomes my favorite thing.

JM: There have been times when we've all sat listening to a mix and thought, "This doesn't sound like something any of us would make on our own." It's like having our hands on a Ouija board.

I've often found on records I've worked on, that the ideas I was reluctant to try, or didn't like end up being my favorite parts. Now I try anything.

DD: That's a lesson that never gets old for me. It keeps me humble, and keeps me open. It also makes me realize how valuable other people's instincts are.

JM: It's funny to be talking about songwriting this much in Tape Op! I feel we're supposed to be talking about things you can control with technology. But the music so often lies in what an engineer can't control at all. Watching that Beatles documentary [Get Back], you see that there's nothing inherently magical about their recording process, but somehow, at the end of it, it's Beatles music.

Yeah, whatever preamps or compressors they used – that are now stupidly over-priced – had the least amount to do with those records.

JM: No matter how one recorded the Beatles, it would have sounded like them. That's becoming more and more true with Loma, I think, as its shape becomes apparent to us. But we're still learning what this band is. I hope that never ends.

How did the Brian Eno collab on Don't Shy Away come about?

JM: On December 26, 2018, my phone started blowing up: "Brian Eno's talking about your band on the BBC!" We listened to the program, and, sure enough, he was talking about our song "Black Willow." He said he'd been listening to it on repeat. It was surreal.

DD: One of the sounds in "Black Willow" is the rustling leaves of a crabapple tree outside the control room. I loved the thought of him enjoying the sound of that tree.

JM: I feel sure he's tired of people asking him to produce records, so I hesitated to reach out at all, but I gathered my courage and sent a letter to his management, saying that we don't want him to produce our record – but if he was interested in collaborating in any way, we'd love to do something together, and he said, "Yes!" We never spoke to him; we just sent tracks to his manager for the song that closes Don't Shy Away, "Homing." A few months later, a 2-track mix came back in the middle of the night. When we got the file, we were looking at each other like, "Well, I guess we've got to listen to this now!" It was a little scary. But it was stunning. It had a depth it hadn't had before. There were a lot of small, significant moves, sonically and structurally. He added a nearly inaudible drum machine at the end. He made a line repeat. He changed the key abruptly at the end.

DD: He also added a strange, almost subliminal harmony all the way through, and did something with the stereo image that I still don't quite understand. In the end, it felt like he'd retained everything we gave him, but also solved the puzzle.

JM: It's rare that meeting your heroes is so satisfying – much less working with them. I loved that he found a way to take all the nervousness out of that, and communicate purely as musicians.

Will you work with him again?

JM: Who wouldn't? But if that was our only chance, it was still really generous of him. It's amazing to have someone whose work we revere not only enjoy something we made, but help us make something new.

How do you mix a Loma album?

DD: I'm usually the one turning the dials and clicking the mouse at Dandy Sounds, but Loma is a collaboration so I'm manning the spaceship as we all navigate. Ideally, we're shaping tones along the way so we don't rack up a huge to-do list that requires us to imagine what it might sound like later. I've gotten to the point where I trust my intuition, as far as knowing when to commit to something on-the-fly and when to leave options. In the end we print an in- the-box mix.

JM: The best thing we can do with mixes, I think, is step away from them for a few weeks. I never listen to roughs anymore.

DD: Perspective is crucial, and elusive – a sonic paradox.

Thanks so much for taking the time to chat. I'm looking forward to hearing the next record!

JM: Us too. We're very early in the wool-gathering stage, so right now we're just making a big mess and seeing what interests us.

DD: I'm very curious to see what crawls out of the cocoon this time.