In 1955, Louis Hardin (better known as Moondog) released a 7” single of field recordings called On the Streets of New York. In it, we hear the street musician performing on –– and almost duetting with –– the bustle of 51st street, the murmuring traffic of West 46th street, and a fog horn on the Hudson. Writer, recordist, historian, and musician Alex Maiolo devised a similar, though more technologically complex concept, which would involve collaborating with Danish musician Jonas Bjerre (Mew, issue #108), Estonian composer and musician Erki Pärnoja, and musical all-rounder Jonas Kaarnamets. Themes for Great Cities was then performed in Tallinn, Estonia, in September of 2021, for the opening of Tallinn Music Week. Tape Op recently interviewed Alex on the premier performance's one year anniversary, in advance of the vinyl release.

What’s the idea behind the Themes for Great Cities project, and how did it come to life?

The idea was we would record sounds from cities and use them three different ways: Ostensibly, in an almost musique concrète way; not-quite-so-ostensibly, where we’d reassemble elements into something you may not even recognize what the sounds actually were to begin with. The third way being more on the subconscious level –– taking ambient city elements, ranging from sounds and light readings, to reflections and water conductivity, and convert those to voltages and gate signals with a modular synthesizer. Once you convert something to volts you can generate notes, because synthesis is basically the assemblage of volts and gates instructing oscillators, VCAs, and filters what to do.

All of this is an allegory for how people relate to cities. There are things that we recognize in municipalities, obviously –– how they look, smell, and feel. Then there are things that affect us on a level that maybe is more of a feeling; and then, deeper, there are all sorts of subconscious cues that can affect our relationship to it as well. This is something I was thinking a lot about during the pandemic when we couldn’t travel. The idea was to celebrate cities that are fantastic but you hear about a little less, perhaps. More Köln than Rome. More Ghent than Paris. It was pitched to Tallinn Music Week, who are an incredibly forward-thinking group. They very generously green-lighted our idea, and gave us exactly what we needed to make it happen. We can't thank them enough. In May of 2022 we did sort of a redux, 100 meters from the Russian border, in the wake of the Ukrainian invasion, in the city of Narva. We are already in talks with other countries about new iterations.

But to begin with, when it was just an idea, we needed time to harvest these recordings, then decide how to organize and assemble them. Which of the three ways I just mentioned would we use them? Which ideas would we abandon?

How were these city sounds captured and used? How long did that process take?

We were given two weeks to put something together. In the first few days, we were out gathering material, then taking that back to this makeshift sound lab we put together in an old Soviet-era building. We harvested ambient audio we’d recorded with iPhones, or took readings from a light meter our friend Mike Walters built for us called the “Mõistatus Vooluringid” (“mystery circuit”), and recorded those voltages. We recorded the clack of high heels in a pedestrian tunnel as a flautist busked, or the squeaks and rattles of trams. We went to ERR, which is basically the BBC of Estonia, and recorded the sounds of dishes clattering and people chatting while eating traditional Estonian food in the cafeteria. We went to the markets where some people speak Russian as often as they speak Estonian. Then we got down to the business of figuring out what to do with all of it. Once we had those sounds stored, we could manipulate them. We converted those sounds and readings to voltages, then ran them through quantizers to make them sound more like a recognizable Western scale. Or used others to animate filters. The modular synthesizer was at the heart of it, but then we involved guitars, keyboards, and a piano as well.

Basically we treat the city as our “fifth band member.” It gives us ideas, and we either accept and work with them, or we shoot the idea down. One of my favorite things we did was take the sound of cables hitting a flagpole in a windstorm down at the harbor. We made a percussion track out of that. Then we extracted gates and voltages from that, using an envelope follower, and used it to advance a bass sequence. The whole thing ended up sounding like jazz, really.

How were these manipulated sounds used in a performance with other humans?

Once all these sounds were compiled, and we knew what we were doing with them, we made a road map out of different movements. For example, the first represented sort of an overture. The second was an assemblage of seagulls aggressively flying over Erki’s car and chattering, turned into a downbeat techno track, combined with TR808 style drums. The next one was dictated by the sound of rain coming down a gutter outside of a popular Telliskivi bar called Tops, then piano was added. One song has a percussion track which is made from the clattering dishes being manipulated, live, into a dance beat, with a vocal tag of a guy asking for sausage, in Russian. It was pulled from some overheard chatter at an open air market.

What we had were basically sections of songs. As we assembled those sections, then we had a good kernel of an idea to work with. Then we made a foundation that Erki and Jonas K. could play guitar and keys over. There were definitely improvisational aspects to it. On that jazzy tune I was just talking about, we took light readings from the harbor, fed them through an envelope follower, quantized them, and ran them through a spectral oscillator. It ended up sounding like an old organ. Erki played on top of that. He had a good idea of what he was going to do, but also had the freedom to stretch out a little bit.

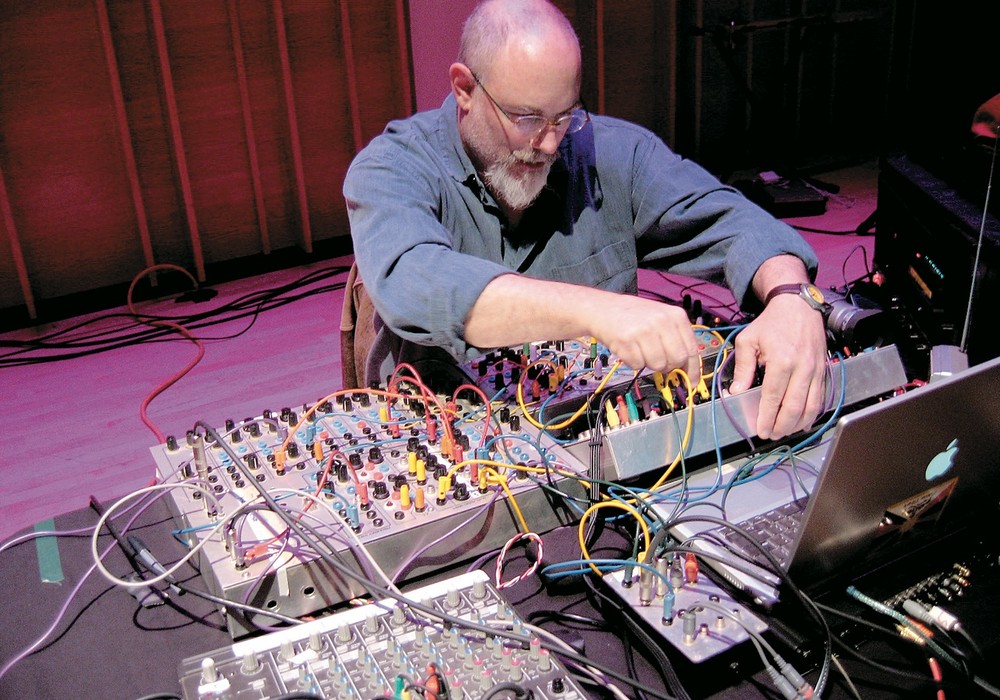

Notably, we didn’t use MIDI for any of this. Had we used something like Ableton I think it would have moved the focus to that platform, and made exploring happy accidents more challenging, in a bad way, so we had a laptop on stage only as a playback device. It may as well have been a tape player. Effectively the way we were set up was this: Jonas B. was playing modular synth. He had mostly Make Noise stuff, but a lot of other modules as well. I had a pretty massive modular kit too, and did most of the foundational work, manipulating sounds Jonas K. was feeding me. Jonas B. reacted to that and made complimentary decisions. He has this gloriously orchestral way of thinking, so he could add really interesting elements. Erki and Jonas K both played keyboards and guitar over that.

The first performance was originally supposed to be in this old shippers guild hall, from the 1500s, that holds about three hundred people. That far exceeded our expectations as to what we were going to be able to do with this project. Next thing you know, we were playing to almost a thousand people in Kultuurikatel, with the president in the audience, broadcast on national television. The first time we’d ever played it!

The recorded audio quality of that performance was so good that we decided to release it, with the help of Helen and the crew at Tallinn Music Week. Of course it needed EQ’ing, some compression, and the like, so we asked the brilliant Kaarel Tamra to do that. Then Adam McDaniel [Animal Collective, Angel Olsen, Indigo De Souza] and I did some production tweaks at Drop Of Sun Studios, in Asheville NC. Like the project itself, it was an international collaboration. My good pal Pete Weiss handled the mastering. The people at Citizen Vinyl in Asheville are so unbelievably helpful when you have an idea. As you may know, massive artists have taken over the pressing plants, leaving small projects like ours out of luck. Citizen were able to work us in, and we pressed it to recycled vinyl. We’ll release that in February of 2023, via Moroderik Musik, and of course it will be on all of the streaming platforms.