How did this whole process get in motion?

Steve Rosenthal (SR): Blondie was at The Magic Shop [Steve’s studio] in 2015 working on Pollinator, which is their last released record. They were upstairs working on a new record, and I was downstairs working on preservation projects. One day I was working downstairs in one of my rooms. I don’t know if Jessica [Thompson] was there that day; maybe she was down the hall. Chris [Stein] came down, and I was working on Dave Van Ronk. He came in the room and said, “What the fuck is this?” I said, “While you are upstairs making new records, I’m downstairs working on preservation projects and historical things.” I told him a little bit about what I’ve done with the Rolling Stones. He said, “You know, I have some stuff in my garage upstate. Would you like to come and look?” Of course, my eyes lit up, and I said, “Yes.” Then he said, “But there’s a problem with it. It’s all been underwater.” There was a flood in the garage and all of the assets were flooded. As the three of us know, because we do this, analog tape is a resilient format. We can triage it, vacuum the mold off, bake them, and then play them. I was not freaked out at all. We took a road trip. It was me, Jessica, Thomas Manzi [Blondie’s management], and Ken Shipley from Numero Group. I thought this would be an amazing opportunity to partner one of these cool, boutique-y historical labels [Numero Group] with a giant, major conglomerate. Which Universal is.

All the proper albums are owned by UMe.

SR: Right. We all got in a big, white van and drove up to upstate New York. I think we went in 2016. We opened the door to the garage, and it was filled with tape boxes and shit that looked like it’d been underwater. That was the beginning of the adventure. We went to Chris’ house a couple of times. Then we drove back everything to the storage facility in New York City and started the process of assessing what we got from Chris’ library and his garage.

As the three of us certainly know, these jobs are not as simple as people might think. Not just getting tapes digitized, but then to figure out how they fit into the narrative of the history of the band.

SR: Yeah. Michael and I have worked on a bunch of projects together in this world. The assessment part of it is so important when we start the archive work. We really have to do a proper assessment, and we create docs for them so they know what they have and what’s on it. Items get photographed, and a lot happens before we get to the point where we’re going to digitize the material.

Did you come up with a numbering system for the reels and all that?

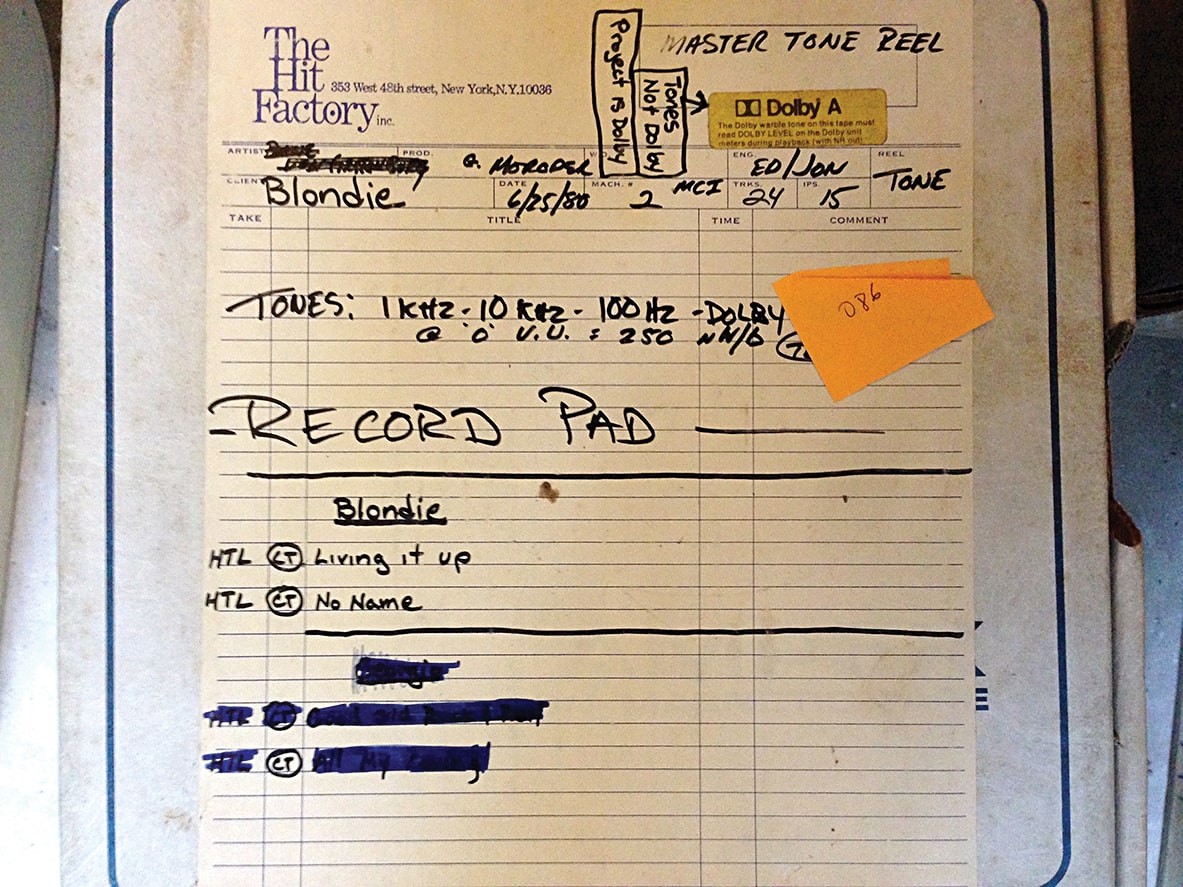

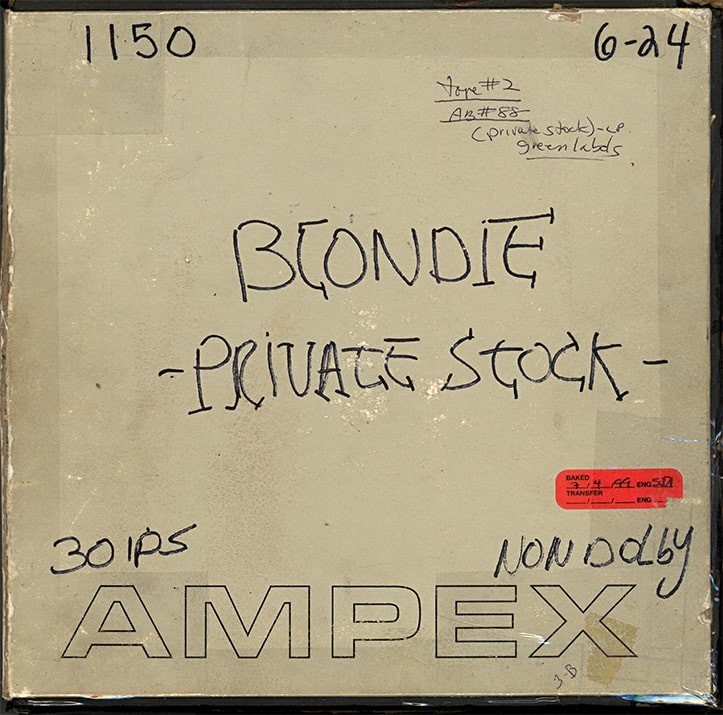

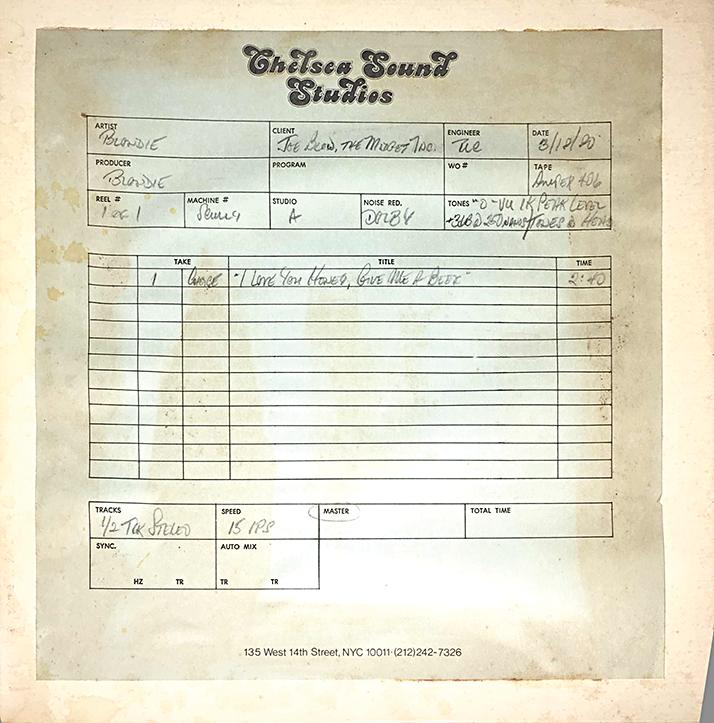

SR: Yes, it was called “Blondie Archive; the BA.” We came up with a numbering system and numbered all of the assets that were in Chris’ garage. The next part of the process was at The Magic Shop. We digitized all [one] hundred or so reels that were in the garage. Kabir Hermon did those. He’s a preservation engineer [Audio Digitization Specialist], now at Stanford [University]. Kabir did high resolution transfers at 24-bit, 192 kHz via Mytek converters. Then Kabir did rough mixes of all the songs that were on the hundred assets. There were lots of 2-inch and 1/2-inch tapes. What other formats were there?

Michael Graves (MG): Didn’t they have a little 4-track?

SR: Yeah, that was interesting. He had a TEAC/Tascam 4-track. Those were challenging. We had to send them to Michael, because they were all speed compromised. I believe to save money on tape, Chris was playing with the varispeed. We sent them to Michael because he’s so great at this.

MG: There’s not much to speed correction. He was doing something in between 3-3/4 ips [inches per second] and 7-1/2 ips, so I had to find the right pitch and adjust it. I’d send it back to Steve and Tom [Camuso] to work on. A lot of this happened before I came into the picture.

SR: The Magic Shop was still open when I went, so the first set of transfers were done in 2016. Then this next part was starting in 2017 and 2018.

MG: Yeah, I came into the picture to do my mastering job in 2020.

SR: Yes. Right before the pandemic.

MG: They were still finding materials up until then. That’s when these 4-tracks were found.

SR: Right. “Ring of Fire” and “The Hardest Part” were found.

MG: I had done the six [proper] albums and we’d done most of the bonus tracks, and Steve was still finding things. We found this “Ring of Fire” that was super cool, but it was so compromised in pitch and sound that it sounded underwater! I did what I did, sent them back to those guys and they mixed it. Then it came back to me, and I did some further work. It was a good team effort to get some of this sounding nice.

SR: I spent almost three years searching through the Universal archive to find tapes. I got access to their big database and spent a lot of time calling up tapes. Some of them we transferred here at MARS [MagicShop Archive & Restoration Studios] in Brooklyn. Some were transferred at Abbey Road. Some were transferred at Pacific.

MG: Pacific Mastering. It’s gone now.

SR: Yeah, out in California. Parts of the Blondie library were in L.A., parts were in England, and parts were in New York. I’m not exaggerating; there were multiple years of searching to find the tapes that show up on the box. After the music was discovered, then we had to rough mix it and send it to the band. Some of that rough mixing was done by Alex Slohm, who worked here for a while. Kabir did a bunch of the rough mixing, and I did a bunch of the rough mixing. We probably sent the band maybe what, 70 songs?

MG: I think so, yeah.

SR: About 50 of them made it to the big box. Some of them they were like, “Oh, I don’t want it!”

It can be political within a band, it can be a quality issue, or just how the band feels about it.

SR: Yeah, it’s a difficult thing. In this case, this is a band that’s still a working band. They just went in the studio to make a new record. The idea of looking back this far is not something that they really do. It’s funny to interact and go, “Okay, this isn’t the person you were in 1974. Are you interested in telling the public what that person was like?” Sometimes they say, “Sure,” and sometimes they’re like, “No way!” It really is a negotiation in that sense, and I have to be very respectful to them because this is their art and their life. This is Debbie [Harry] and Chris and Clem [Burke]’s life. I have to be respectful for what they want to leave in and what they want to keep out.

MG: That’s a pretty common scenario. Steve and I work in this catalog world of the music industry, and a lot of times, especially if they’re a working band, they don’t care about looking back. They’re all about looking forward. Which they should be. It’s more of a producer and fan initiative to say, “Hey, let’s look at the old stuff again.” A lot of times they have to be convinced that this is a good idea, because they’re always forward-looking.

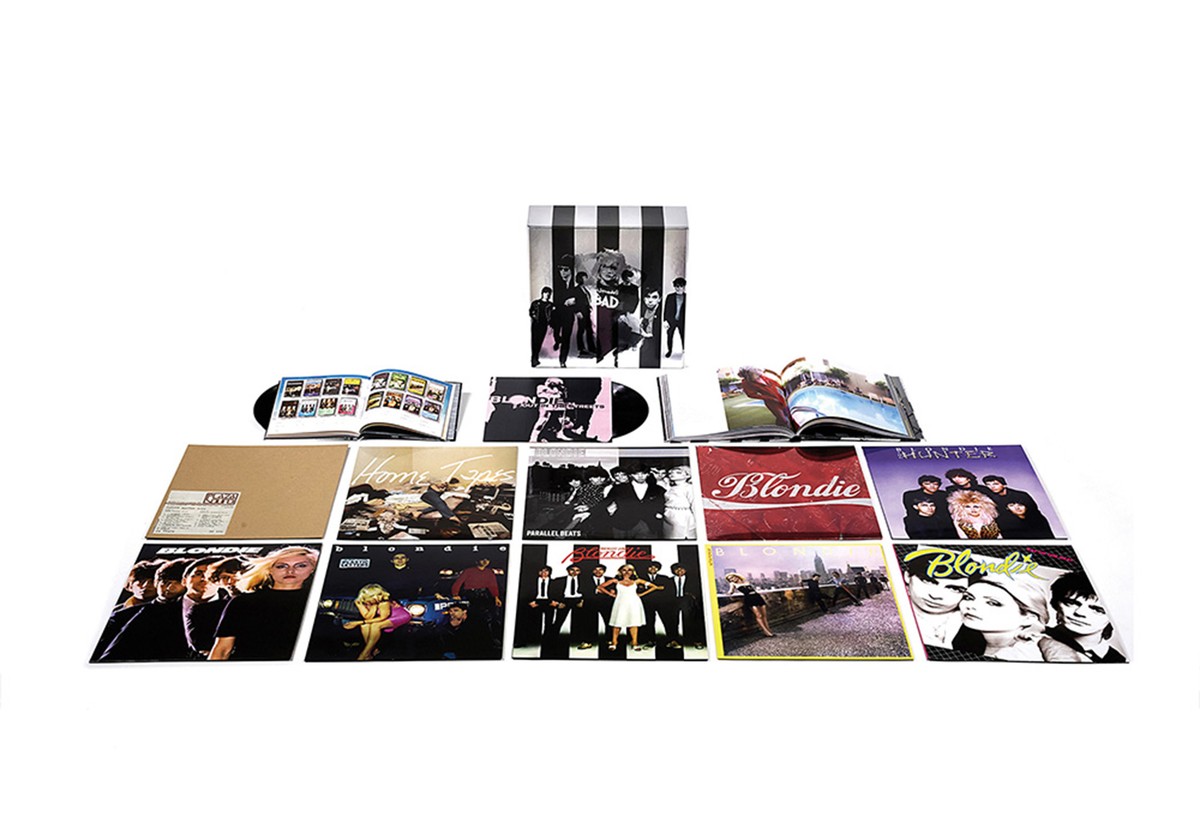

Right. In the case of Blondie, these albums have been remastered and re-released a few times. The first version of Parallel Lines on CD was dreadful.

SR: One thing we realized, and Michael can speak to this too, is that the band never had anything to do with the other remastered versions of their classic albums.

MG: When we first started this, I don’t think we originally were going to remaster the first six albums. They’d been remastered in 2001. I looked at the files and thought, “If there’s ever a time to revisit all of this material, this is the time to do it.” Because they had been remastered so many times over the years, the compression kept seeping in and seeping in. When we compared some of the later CD reissues, it was so drastically different from the original pressings of the records. Steve and I went and got all the original [LP] pressings to use that as a reference and a starting point. That’s our guiding star. “If we can get it as good as that, great. If we can get it better, that’s good too.”

Whatever was done in the mastering process to create those original lacquers was what the band and producer signed off on.

MG: That’s right. Also, it was a little bit nerve-wracking on my part to make sure the band was happy with all this, but they approved everything. It makes me feel good. I always like having the band involved in these decisions. It always feels weird when I’m on a project and it’s just me and a producer. But I work [on projects] with a lot of musicians who are no longer living, so it’s part of the job.

Once they were signed to a major label, bonus songs that weren’t demos must have been in the archives at UMe?

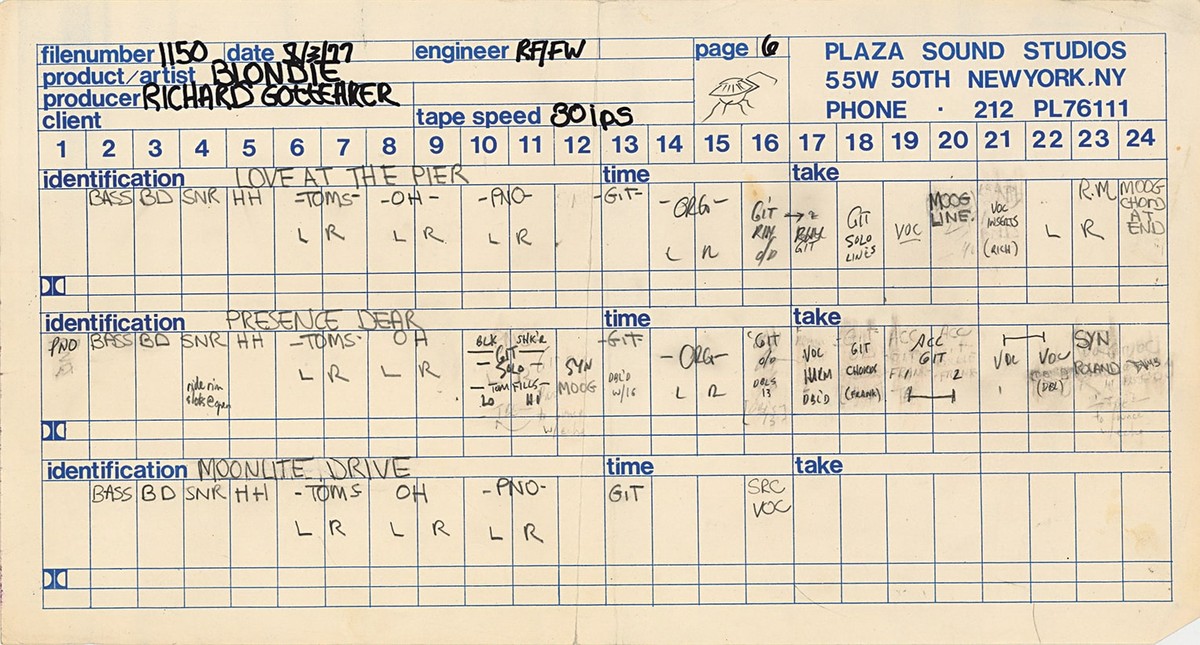

SR: Yeah. There was an amazing amount of material that I called up. All of the multitracks were called up. I had a couple of fine assistants at the Universal archive to help me look through this and then call it up. Kristina Fox was amazing. She was so helpful. I’m a bulldog when it comes to this, and I tend to go after DNUs [“do not use”]. I’m old enough to know that sometimes they’d put “DNU” on a tape for the wrong reasons. Maybe they wanted them to use their Dolby stereo tape copy, and they don’t want anyone to use the original analog without Dolby on it. I’m old enough to realize that’s part of the dance. I always call up a lot of DNUs. Now, thankfully because there are so many engineers who focus on preservation, the label’s not scared of the DNUs. Twenty years ago, they wouldn’t call them up. They’d just go, “They’re not playable.” Universal was more than willing to let me do that and do new transfers. That’s how I found [the cover of] “Moonlight Drive.” “Moonlight Drive” is one of those songs that Blondie fans always talk about. They played it live back in the day, and did this really burning version of it, but there were no studio recordings of it. It’s one of those songs that people ask for. I kept calling up multitracks, and then one day, in one of the Plastic Letters series of multitracks, there it was! I saw the track sheet. It was there. It had a vocal. Chris is not happy because the intro was not recorded. The guy turned the record button on after the song had started already.

No!

SR: That happens sometimes. But at least we got two verses, a bridge, and an ending. That was a great find; now people can hear it.

MG: Didn’t you say that of the bonus material, about 60 percent of it was from the garage, and the remaining was from the archive?

SR: Yeah, the other remaining part was from the Universal archive.

It’s amazing that Chris had that much. He’s been the headmaster of the band for their entire career.

SR: It’s so wonderful. There are a whole bunch of live recordings that were in the garage. Maybe if this box works, and people go out and buy it, they can get some classic Blondie shows out from that period, as well. The other thing in the garage is Chris’ Animal Records catalog.

I assumed all that would be there.

>SR: There is some cool shit. John Lurie and the Lounge Lizards, James White and The Blacks, and Iggy Pop. That was a cool label back then [1982 to 1984]. Hopefully maybe down the road that will see the light of day.

Going back to the albums proper, I’d never heard the first album, Blondie, or Plastic Letters so clearly. I had to keep looking at the notes and see if you had remixed it. I always thought the first two records sounded murky. No offense to anyone who worked on them back then.

MG: I thought that the tapes were just like that. That’s one of the situations where I took it up to where the original LP pressings were, but there was more there to give. I started pushing it a little more, and it always sounded great. I tried to clear it up a little more. I was happy with it. That’s the one thing I wasn’t sure. It’s always tricky to mess with the sound of something that’s so beloved. Even if I think I’m improving it, fans have an attachment to that sound, regardless of if it was good or not. When I’m remastering classic material, I can make myself crazy if I’m trying to please everybody in my head –the original production of the band, the fans, and the original mastering engineer. At some point, as a mastering engineer, I have to trust my ears to do the job that I was hired to do.

Yeah. It’s hard. I’ve been on that front with remastering the Elliott Smith [Tape Op #4, #11 #118] catalog. It’s hard to say how far to go.

MG: Yeah, right. I don’t always do a lot of big name bands like this, so I can flex my muscles a little more if it’s some obscure regional band, or some jazz band from the ‘40s that no one’s super familiar with. I can do what I think is right, and not worry about any fan backlash. But this was a little bit different. It can’t be debilitating, but it’s got to be somewhere in my head that people are going to judge this a little more critically than other projects.

Oh yeah. I’ve gotten comments!

SR: Michael did an amazing job on those first two records. When I was a kid, I bought the first record on Private Stock [Records]. A bunch of those Private Stock mixes were different, and some part of my archive search was to find the masters for the Private Stock version of the record. They were different mixes from what came out when they got signed to Chrysalis [Records]. In the box set, there are a number of tracks with the original Private Stock mixes. Sometimes they have double-tracked vocals, sometimes the arrangement’s a little bit different. Michael did a fabulous job mastering the early records. Plastic Letters is a really good record. It’s not looked at with a lot of reverence, but after what Michael did to it people are going to hear it in a different way. They got shit for being so punky with that record. That record’s not a pop record; it’s more like a punk record. Looking at it now, it’s a pretty killer record.

MG: One of the albums that I wanted to focus on – because I like the underdog – was The Hunter. There are some great songs on there. One of their problems was a lot of compression happening there, and, again, it was sort of dull. I don’t know, nothing sonically jumps out and grabs you. I wanted to try and give some of these songs a new lease on life. It might turn somebody on to some of this music. I wasn’t familiar with that record at all. I had no idea that they had a James Bond theme song on there, “For Your Eyes Only.” This is a killer version of a 007 song that never came out.

I know! “Island of Lost Souls” and “English Boys” are great.

MG: Yeah. The first song on that, “Orchid Club,” there are these heavy jungle drums. It sounds great.

It sounds like The Cure, like their Pornography album.

MG: Yeah, it totally does.

This box set wraps up right after The Hunter, as Chris got really ill, and the band disappeared for a number of years.

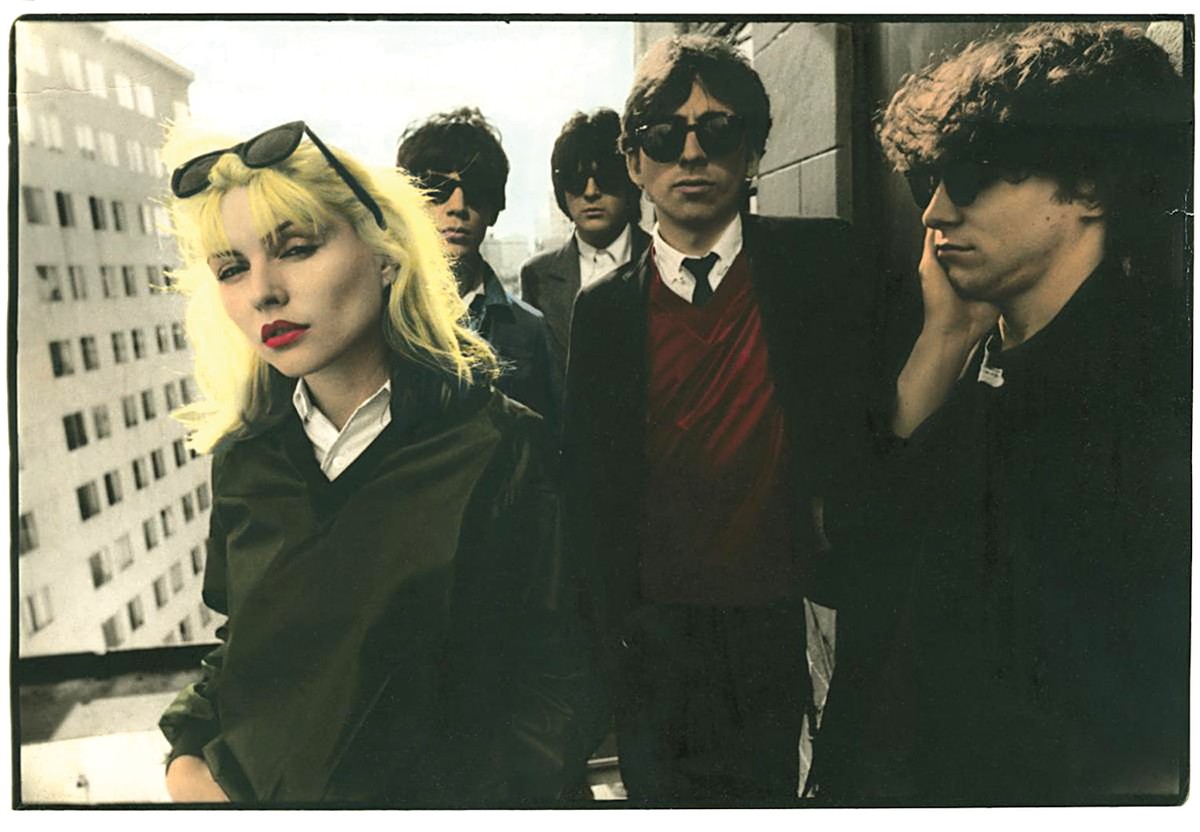

SR: They took a hiatus. That’s why this timing made so much sense, to go as early as we could. We found those Stilettos rehearsal tapes. Before they were Blondie, Chris and Debbie were in that band with Fred Smith, from Television. It really is the genesis of what turns into the band. Then there was this hard cutoff date in 1982. That’s why the box is based on this 1974 to 1982 time frame.

MG: Yeah. There were a couple of cool mixes that were a few years past our year constraint that Steve and I would have loved to have on there.

SR: Oh man, there were some that Chris did in the studio.

MG: One of them sounded like New Order. It sounded great.

SR: It was a year and a half or two years after our hard cutoff. I kept putting them into the sequence, and I was hoping no one would notice. They were fabulous instrumental early-’80s synth-based pop tracks. I think it’s all just Chris in the studio working.

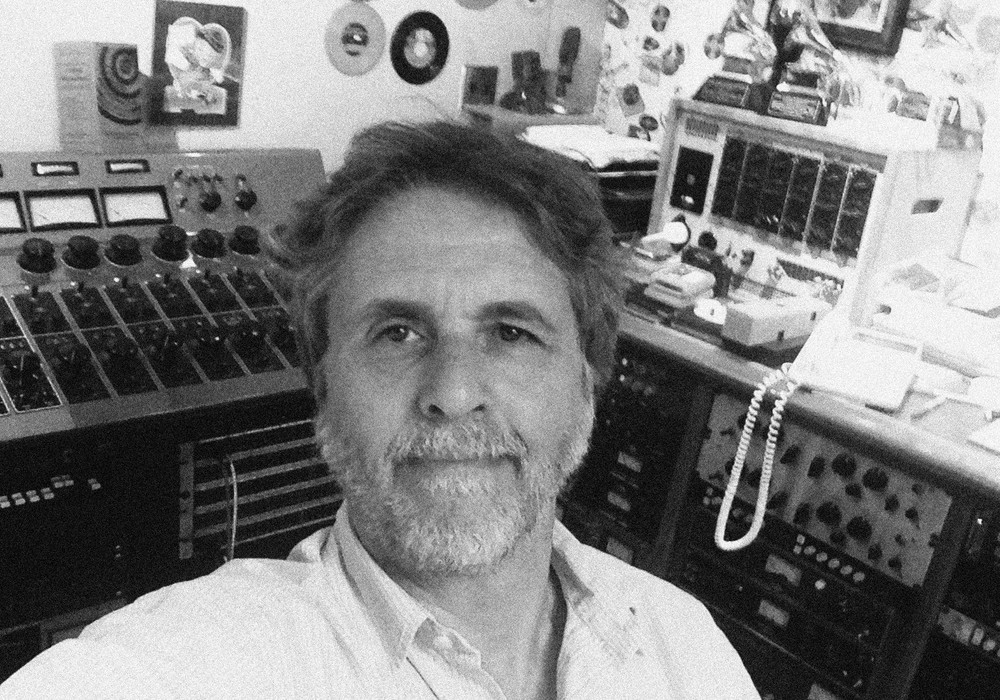

Most of the unreleased tracks required new mixes, right?

SR: Tom Camuso’s the engineer who I worked with to mix all these tracks. He’s brilliant. He’s an ex-Magic Shop guy. After he left, like most of them do, he opened up his own studio. He opened up one in Brooklyn called Studio E. It’s a great place. He has a Neve 8014 [console], and it’s in great shape. We did all of the mixing for the Blondie box on the Neve console at Tom’s place. A lot of it was done during the pandemic, so I wasn’t in the room with him. I was on the phone or Zooming with him. He really understands historical mixing. We’re not mixing a record for 2022. If we’re mixing a tape that was made in 1978, we need to honor the sonic blueprint of life in 1978. Tom spent a lot of time trying to be accurate yet making sure that the fidelity worked and that the band was big enough so that it could be played alongside a lot of records. He is a brilliant engineer who worked way beyond time and money, and so did Michael as well.

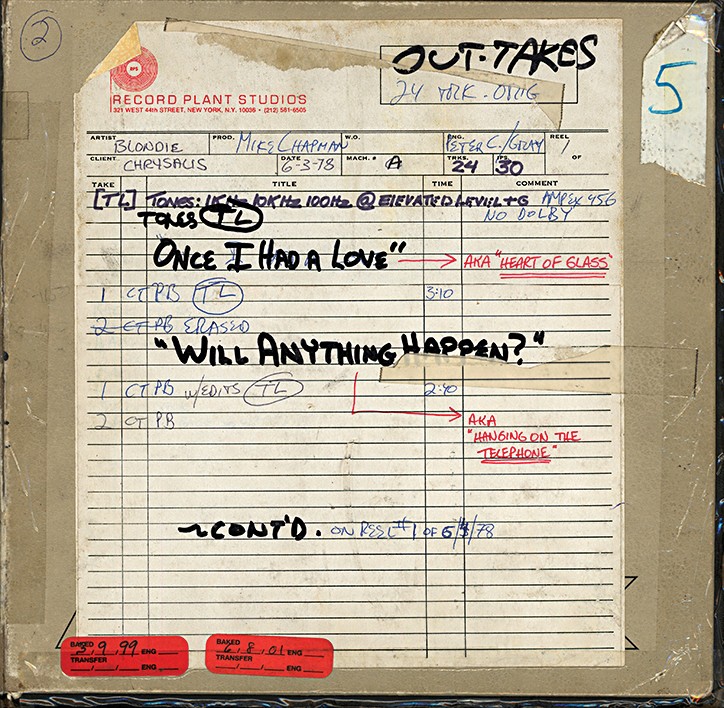

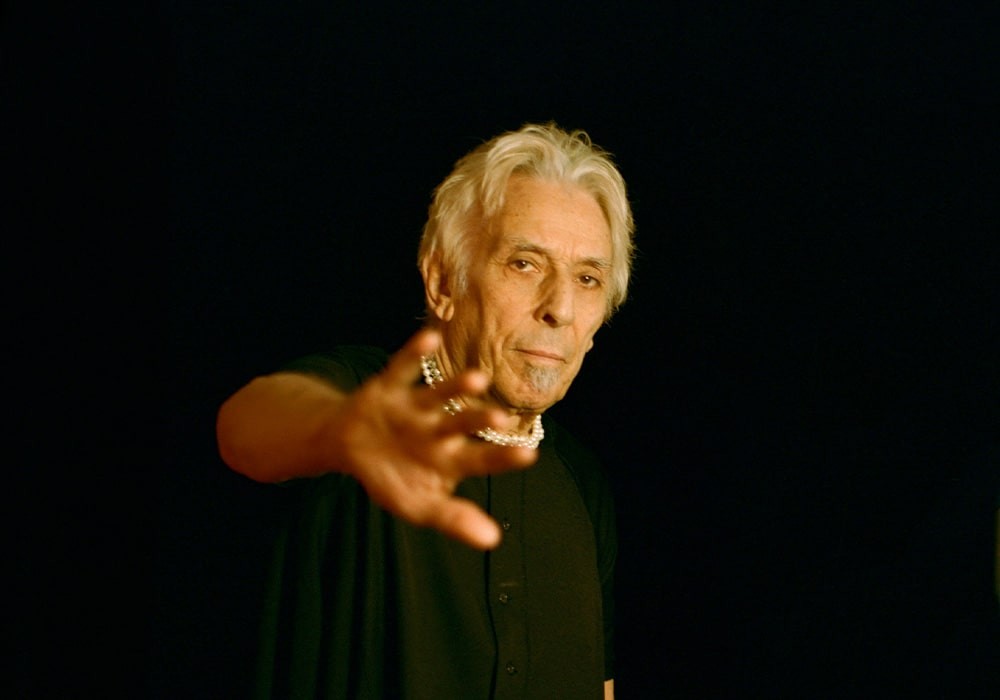

Mike Chapman practically invented how we see records produced these days. We hear “Heart of Glass” as demos and run-throughs, and there’s something a little wrong. Then we hear that Parallel Lines version, and it works, but it’s not a band bashing it out, it was built brick by brick.

SR: Yeah. Both Chapman and [Richard] Gottehrer wrote essays in the included book. Both of them did a brilliant job producing Blondie. “Heart of Glass” existed in 1974. In terms of the lyric and the melody, it’s probably 70 percent of the way to what we know. But the presentation was not right, and it’s wonderful that we get to see how they evolve on it. There are four versions of “Heart of Glass” on the box.

MG: I feel the same way. The fact that the song goes back to almost the beginning is pretty amazing. On Parallel Lines, it clicked. Something went right. It’s such a killer song.

“Rapture” is another song that’s also a studio construction.

SR: Chapman is amazing. He’s brilliant. He did an incredible job on those records. It was fun to notice we let him sing on the box set. There are a couple of tracks where he’s doing lead vocals! To show that’s the level of participation here. He wasn’t sitting in the control room going, “Louder, lower, faster, slower.” He’s in there singing and outlining what the melody’s going to be. I’m so happy that they let us keep that. It’s so crazy to think they traveled this journey from CBGB to the Garden. They obviously sold a lot more records than any of the other bands that were around.

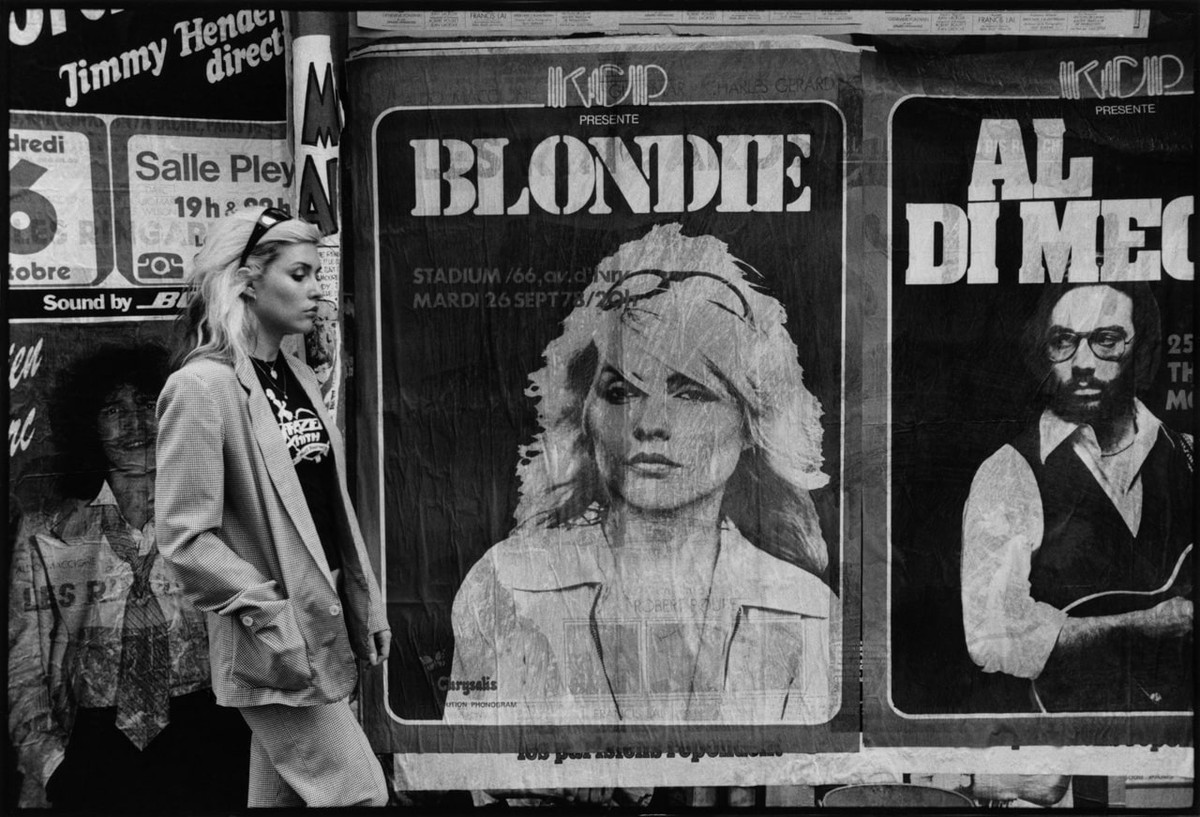

I’ve read quite a bit about that era and it’s amazing that people would say, “Oh, that band is silly.”

SR: A lot of it is sexist dude bullshit. Guys dealing with her and what she meant. Some of it’s that, but you’re right, they got a lot of shit in the early days. Think about the box set title [Against The Odds]. They’re the ones that named it. It speaks to the journey that they had as a band. That they felt they had to fight to get where they wanted to go. It’s interesting.

I felt the tension reading through the liner notes, of how much product and touring they were expected to take on.

SR: Erin Osmon, who did the track by track [liner notes], did a fabulous job to get them to focus and talk about everything.

Thanks so much for all the hard work on this set! I love this music so much.

MG: It’s rewarding. It’s pretty solitary work looking at an iZotope RX spectrogram, but it’s rewarding at the end of it when I can take something that’s completely unusable, and now we have a song that people can enjoy. I use the Azimuth correction in RX a lot. It always saves my butt. I get tracks that people think are stereo because the azimuth is off. It’s really mono!

I’ll use it on stereo drum overheads to azimuth correct them.

MG: I never thought about that. I’m always thinking about tape-based work. I didn’t think you could use that for something else. Have you ever tried Zynaptiq software?

No.

MG: You should check it out. One of my favorite ones is called UNCHIRP, addressing the problem of MP3 artifacts. It’s trying to diminish those chirpy sounds or watery sounds. It’s not perfect, but sometimes I can dial it in and minimize it to a point where it’s much more acceptable. As you know, if we have to be heavy-handed in the restoration, sometimes we can get those same artifacts. I’ll follow that up with UNCHIRP, and it sounds great. There’s another cool plug-in you should check out called UNFILTER. It gets rid of comb filtering, and it’s amazing. You can put it on a track that sounds like somebody singing into a Dixie cup, and it clears it up immediately.

I’m on it.

SR: It’s great to hear Michael talk about the tools that he uses. Sometimes I send him shit which I feel is unfixable, and a week later he sends it back to me and it sounds like music.