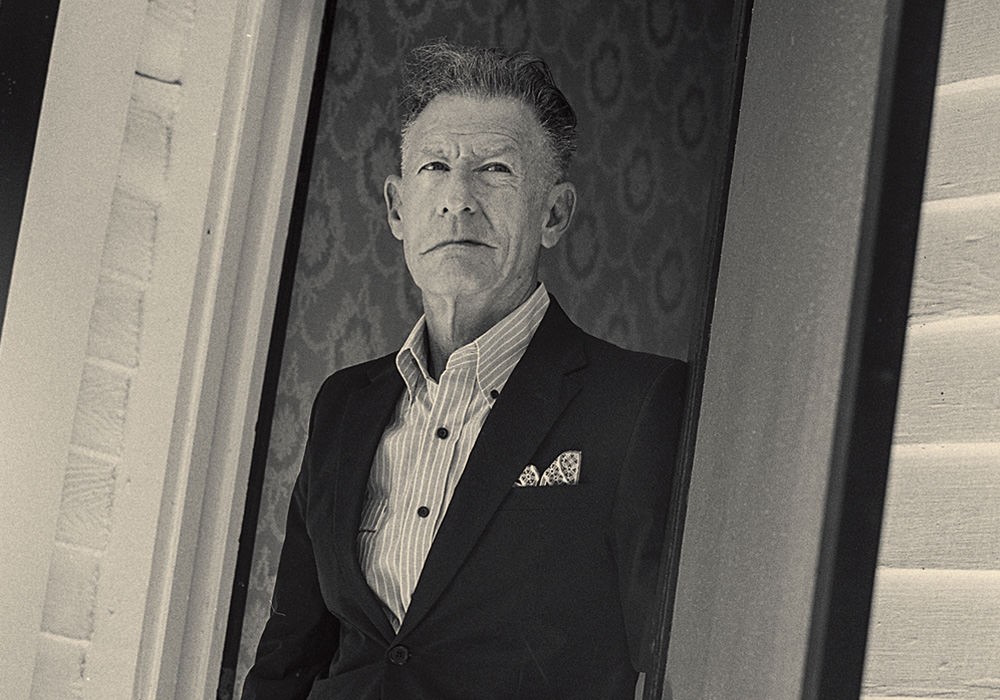

What was it like growing up in Sayreville, NJ? Did you come from a musical family?

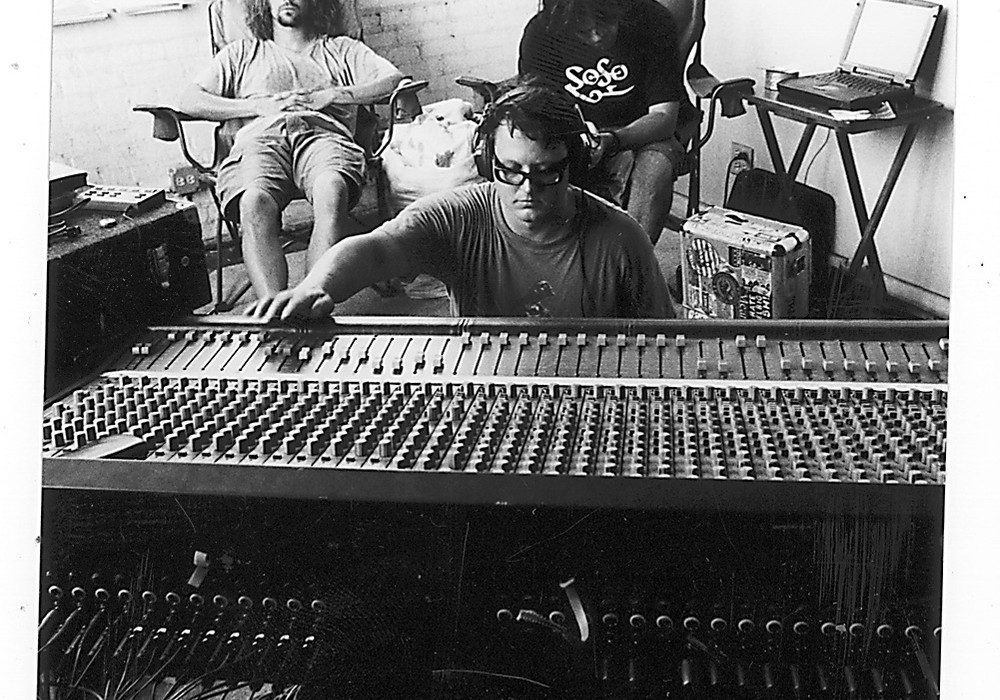

I grew up in a pretty normal household. No musicians in my family, but it was always in our house, and I was drawn to music early. I played piano a lot as a kid, but never saw it as a career path. It was always just a hobby and a passion, up until my early twenties. I did well in school, and it was always, "You're going to be the doctor in the family." I didn't even know this existed. [points in direction of his console] I only figured out later in life, "Wait, that's somebody's job!"

What was the local music scene like?

I was always in bands. I came up in the New Jersey hardcore scene with my first real group of friends when I got out of middle school. That time ['97 to '99] was an awesome explosion of local music. Later, I was booking shows, running a little record label, and it was cool to be on the ground floor for a lot of these seminal bands [The Dillinger Escape Plan, Deadguy, Ensign]. I was very active in music, but, again, it was just all for fun. My family was still, "You're going to be a doctor when you grow up." [laughs]

It sounds like you had a strong math and science background.

I got good grades and gravitated towards that. We were talking about going to the Ivy Leagues, but financially it didn't make a lot of sense. I wound up going to school in Hoboken for biomedical engineering at Stevens [Institute of Technology], which is a great school. That was my career path at the time. They had just started a music program, and I was there for one of the first years. I was taking recording classes and music theory as electives between science classes.

Do you feel there's an intersection between science education and music?

Every producer that I like is hands-on and has both sides of the brain working. There's a very technical, analytical side to engineering and, obviously, the creative side of it. There are the people that are off on Mars and couldn't do a math problem, and then these unbelievably clinical engineers who can't write a song. So, if you're going to be a one stop shop and do it all, you need both sides of the brain working. I figured out early, "Oh, there's this other part of recording that isn't just fun and jamming with a band." There's a lot of computer work and science behind audio. If anything, it trained me to analyze and think critically. Also, to problem solve in a different way. If I had only been a musician since the age of 13, I probably would've lacked some of my skills in the studio today.

Around this time you got a taste of working in the corporate world.

I worked for Lysol, or rather the mega corporation [Reckitt] that owns them. I was in a microbiology lab, and I found out pretty quickly that it wasn't creative. At that time, research and development was nonexistent for a lot of companies. It was more about re-engineering current products. "How can we make this work better and cost less?" They were interested in mechanical engineers because they needed to make things work cheaper. The repetition and monotony got to me pretty quick and I realized I couldn't do that my whole life.

If you're going to be doing repetitive monotonous work, it's got to be in audio!

Yeah. I'd rather do it a million times here. [laughs] But the landscape is always changing for a producer, and every band is different. Every dynamic is different. I'm always trying to go for a new thing or sound with a band, and it's always an exploration. That is non-existent in that [corporate] world.

Escaping Lysol, you began interning with Gene Freeman [a.k.a. Machine] at his Hoboken-based studio, The Machine Shop.

One of the recording classes that I was taking shared a...