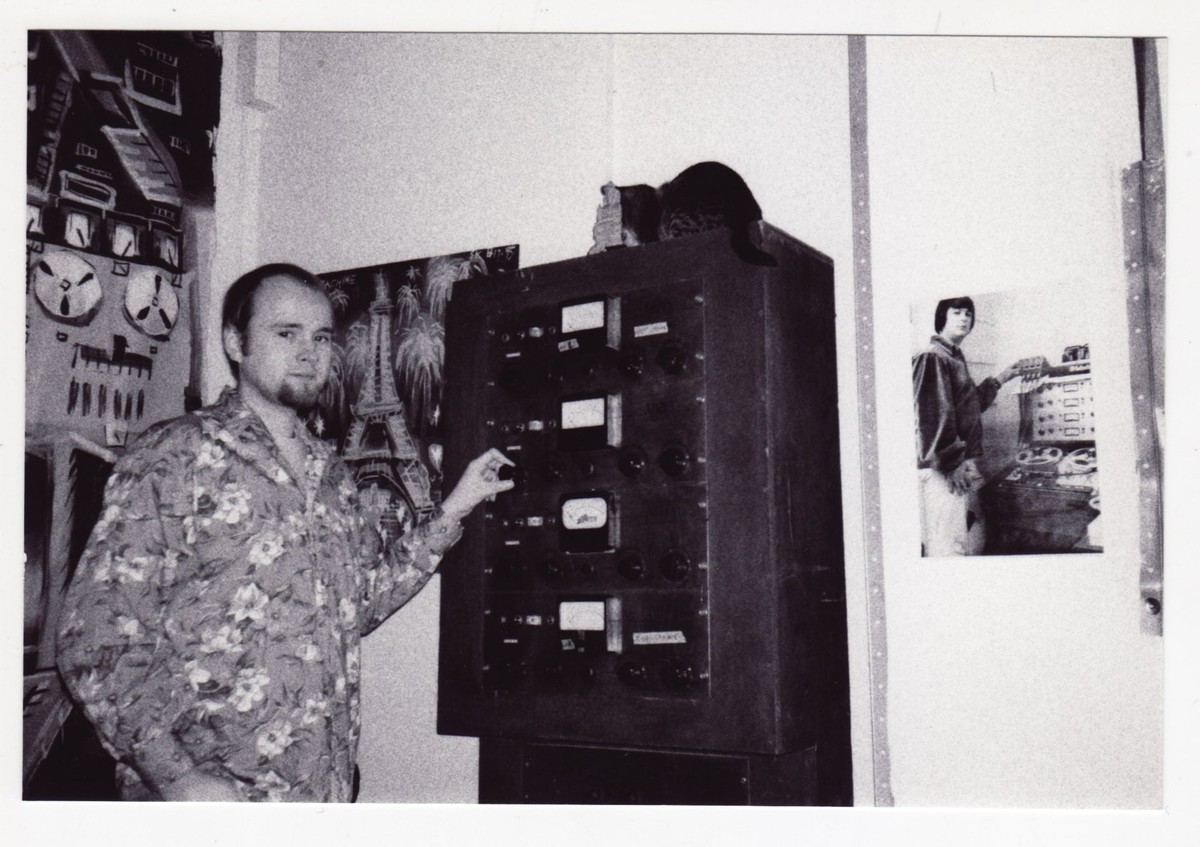

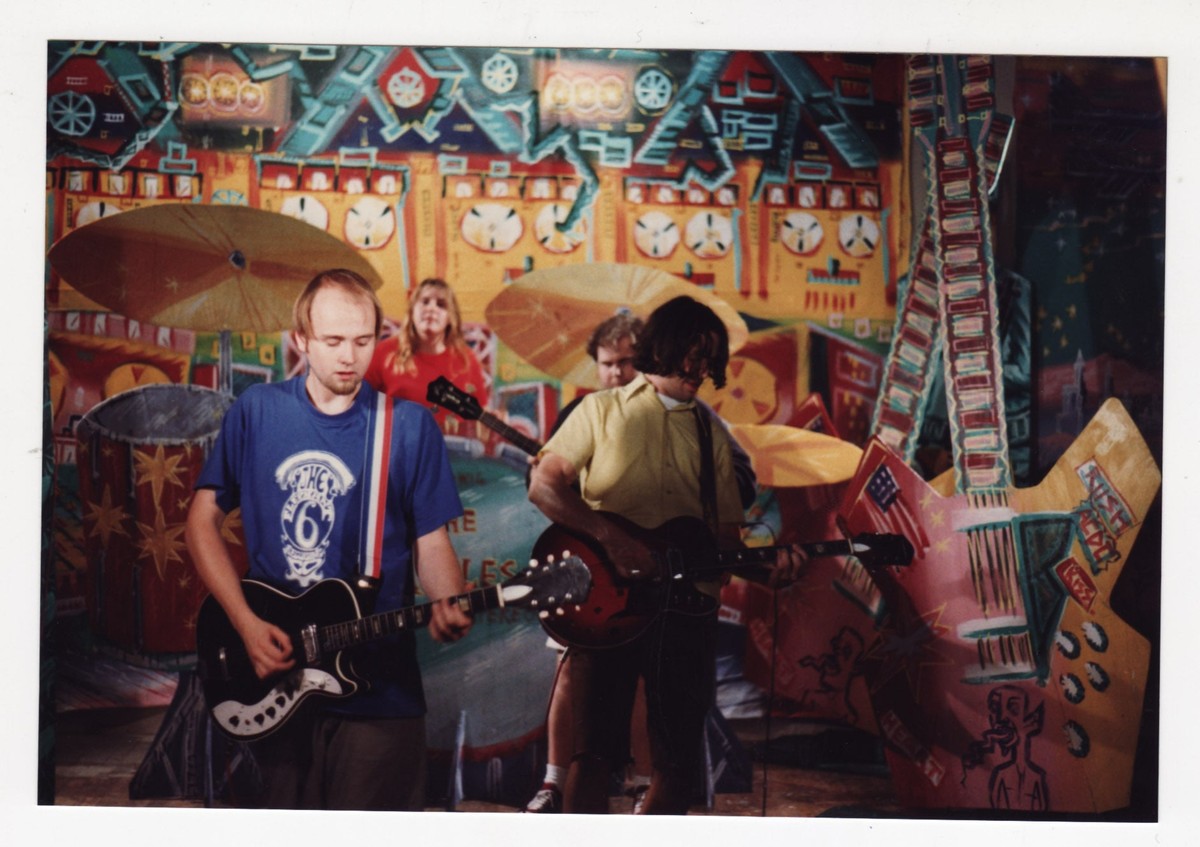

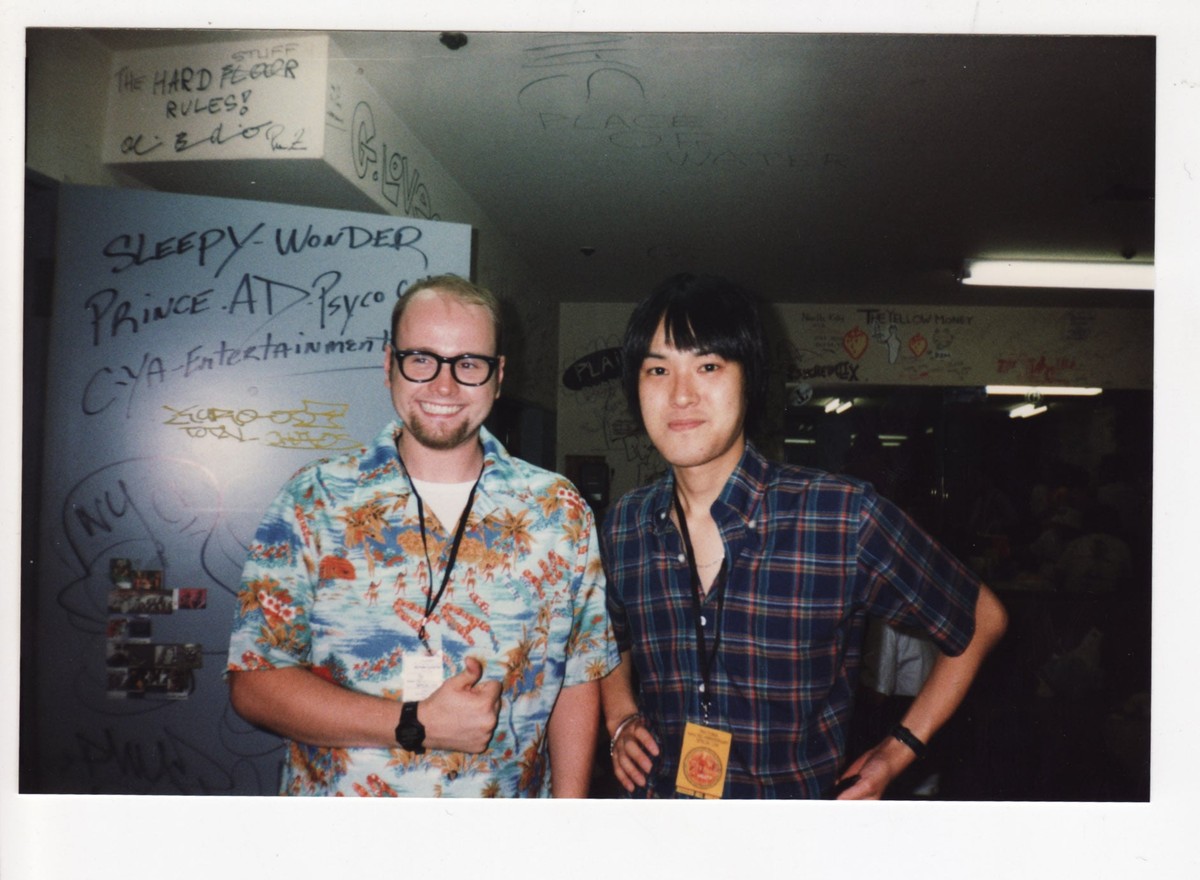

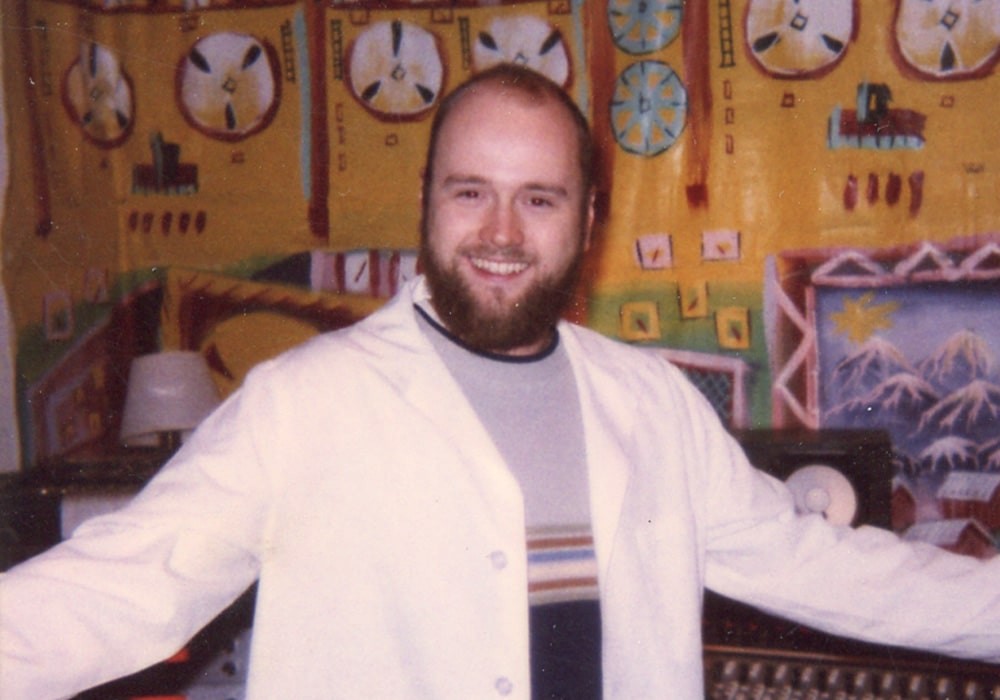

On April 14, 2018, at Jackpot! Recording Studio, I interviewed Robert Schneider in front of a live audience. Afterwards, he did a short solo set, and then The Minders played – a band both of us had recorded albums for and are friends with. Robert and I first met in 1996, when I interviewed him and The Apples In Stereo for Tape Op #2. Alongside some classic Apples and The Minders albums and other projects he's in, he recorded and produced records for Neutral Milk Hotel [#11] and The Olivia Tremor Control [#17] and co-founded The Elephant 6 Recording Co. (See the wonderful The Elephant 6 Recording Co. documentary that we are both in). Now, with his recently attained Doctorate in mathematics, we sat down in front of a live audience to chat again! Check out the podcast of this conversation as well!

There was a band called the Thinking Fellers Union Local 282 in the Bay Area.

God, they're so good.

I interviewed Hugh Swarts from the Thinking Fellers for issue one of Tape Op. I asked, "Anything cool you've heard lately?" He said Fun Trick Noisemaker by The Apples In Stereo.

Oh my god. You don't understand. We worshiped Thinking Fellers. That's awesome that he said that. They're one of the best bands ever.

Oh yeah. When I was in Vomit Launch, we used to play lots of shows together and sleep on each other's floors and drink too much beer. They were great.

Their music was so intricate. It's really catchy. It's amazing.

So, I went and listened to your album. You were coming through town. The Apples In Stereo came and played at Mt. Tabor Theater, which is now known as QuarterWorld.

Is it a video arcade?

It's a really fun video arcade.

It wasn't a video arcade when I played there! That is the true tragedy of the situation.

We sat outside and did an interview at a picnic table.

Yeah, that's right.

We were sitting out there, and we did an interview late at night on Hawthorne, just a few blocks away.

We should all go down there and do this interview!

Bring your quarters. The interview was in 1996. It came out in the second issue of Tape Op. Xeroxed.

Tape Op, for one thing, was a zine at the time. It was a home recording zine, and it was by far like the hippest recording magazine and zine of all time. I was really proud you included us in it. Thank you.

That was part of the journey of doing Tape Op, if I can turn this all about myself for a moment, was meeting so many cool people doing things in different parts of the country as well. Talking to you, turned me on to The Minders. When they moved out here, it was like, welcome The Minders. They're friends with Robert and everybody. It definitely builds a community too, the like-mindedness of everything.

Yeah, totally agreed. Being in music is great that way. Music is like this thing that humans do that brings us together. We use it when we're together too. It's really cool.

I remember you telling me about laying on your bed playing guitar solos really, really stoned.

I'm neither going to avow or disavow the statement.

Now that you have a Ph.D.

I'm just being clever. Yeah. Yes, yes. I'll fess up to many uh metaphysical guitar playing experiences in my life.

On another plane. I'm going to skip back in history a little bit, way back. What was the origin of your 4-tracking and 8-tracking and stuff? Was it just necessity? Recording your music and your friend's music?

Okay, I can easily answer the necessity thing, and then I'll go into the other thing. For necessity no. it was the fact that we hated the sound of stuff that came out of commercial studios. Like the idea of going into a place and having them make you sound different from the way you felt you sounded, which felt like it was the case at the time.

Like '80s music and stuff?

Yeah, '80s music. This was the '80s. Number one, that didn't appeal to The Apples or my friends in the Elephant 6 Collective. We wanted to make our own sounds. If you're an artist, you don't go somewhere else and you're like, "Eh, I'd like to paint a face there. Can you paint a face for me?" They're like, "Eh, is this like it?" You're like, "Nope! It's photorealistic. I was thinking more primitive." That's what going to a studio felt like.

"Watercolors, please."

Yeah, exactly. So, I think it wasn't out of necessity. It was aesthetic choice plus necessity, because we were all so broke. But that didn't matter. I started recording when I was probably in 6th grade. I figured out what many people of our age figured out. You used to be able to get these really awesome dual-cassette boom boxes back in the day. I'm sure you can still get them. But they had this feature. You could dub cassettes from one to the other. Also, boom boxes had built-in mics, and they sounded great. That's a great way to record. So, you could play a tape on one of the tape decks that you would use as a dubbing deck, but you could have it set up so that the microphones would be live. The microphones are picking up the tape you're playing, and they're also picking up the sounds in the room. You would probably discover something like that by accident, like I did. This lady who lived in the neighborhood, who was the mom of one of my sister's friends, hired me to make her a series of heavy metal compilations, because I was really into heavy metal. I started up a little cassette label when I was in 6th grade to dub off these bootleg heavy metal cassettes for this woman. So, while I was dubbing up the cassettes, after I got through some volume of it, I noticed that me shuffling around the room was on the cassette. I was mortified. "Oh my god!" Then in the same moment I realized I could play music off the thing and play along with it, and then it would be recorded plus have the original music with me playing along with it. You could do that back and forth. That's just ping-ponging and home recording. It sounds great. It's really awesome. I still do it sometimes when I record. That's how I started recording. I probably started recording before I started playing music. My parents gave me a synthesizer in the early '80s.

Wait, stop!

Radio Shack manufactured a synthesizer, the Moog. In the early '80s. It's like the best synthesizer ever. The Moog [Realistic Concertmate] MG-1. Concertmate was Radio Shack's brand of keyboards.

There's a Radio Shack SK-1 copy [Realistic Concertmate-500] back there that Casio made.

Radio Shack was owned by this corporation Tandy. Radio Shack would have their version of all of their products, including synthesizers. But actually, that wasn't just a knock-off. It was made by Moog for Radio Shack. Anyway, my parents bought it for me for my birthday. There was a secondhand one. I really desired it as a child, my whole childhood. I started to record with that and the boom box. That developed over some years to me starting to pick up on 4-track. At the same time, all of my friends I grew up with and started to play music with, I grew up in a small town in Louisiana called Ruston. Some of my friends that I ended up forming the Elephant 6 Collective with, we would trade cassettes and do boom-box recordings back and forth. I think I was the first one to do multitracking like that, so mine were slightly more elaborate. It would have a guitar and also a guitar solo or something like that. It was crap, but it would have two things instead of just one thing. Where was I going with all of that? Okay, flashing forward some years, there was this guitar store in Ruston. They had like a demo 4-track. The 4-track had like a demo tape. It was a Fostex X-15 4-track, which is a really great sounding tape machine and also mic preamp. The demo had some band for Fostex playing a 4-channel song, so it's like here's the drums, here's the guitar, here's the bass, and you could sit there and mix it in the guitar store. It felt so magical to do that. My guitar teacher turned me on to the fact that you could rent the 4-track for $5 a day.

What?

But if you rented it on Friday before closing at night, you're basically renting it for Saturday, but they're closed on Sunday, so you didn't have to turn it in until Monday. So, you could have the 4-track Friday through Monday for $5.

That's pretty much an album session right there.

It was awesome. I went with my late friend Bill Doss [The Olivia Tremor Control], who's one of my best friends and bandmate; a lifelong musical bandmate. We went to Haymaker Guitars, and we rented the 4-track for the weekend. We went over to my high school, because it was the only place I knew that was private, because I didn't want other people around. This was the outdoor bus stop at the high school. I had noticed that the outdoor bus stop had an electricity plug. I'd always fantasized about going there and plugging in my guitar and playing really loud, just blowing away all the kids at high school. They'd go like, "What is that noise?!" In fact, I did that once. I did a book report for my freshman English class. I read the autobiography, but my book report was I went and played [Jimi Hendrix's] “Purple Haze,” and I had a dashiki and shit, so I did get to live out that fantasy too.

No one shot video, huh?

No, I don't think so. That was before video. So, we went and recorded a song at the bus stop at my school. It was my first 4-track recording experience. I spent the whole weekend working on it. It was very elaborate. I already knew how to ping-pong and stuff, because I'd figured it out on the boom box. It had all these pianos and harmonized lead guitars and harmonies. It was a very, very pretentious song. It was pretty great, I think. That was my first recording, and my first song I ever wrote. I've always been recording. It's just part of what I did. I've always seen it as part of the songwriting process for me. Songwriting and recording kind of go together. That's my instrument. Just like you might write a song on guitar, and obviously you're going to play it on the guitar. I can write a song, and I'm going to play it on the recorder. It worked out. That's why I've always wanted to home record, whether it's a 4-track or whatever. To be in control of it, it's like, are you going to tell someone else to paint your painting or play guitar? But that doesn't apply to you! You are the most amazing audio engineer, and I would tell you to paint my painting any day.

I mean, I understand. It's like when, we write about this a lot in the magazine too. If you hire a studio and go in and you haven't done the preproduction part of saying, "Is this the right person to work with our band? Does this person understand our music? Is this person going to be punching the clock, and do they care who we are? Are they going to be actively engaged?" The first guy I ever went to the studio with was drunk and couldn't find my backing vocal part over and over. "Try it again!" And he was drinking wine coolers. It gives you an idea of the decade this might have been.

Oh, that sounds great! Wine coolers.

1985.

That's awesome. No, but you're right. I guess the thing is that a studio's a great thing for a band to go into and rock the fuck out for three days like Black Sabbath, MC5, the Velvet Underground, or something. You make a great record where you're capturing your band. The recording is done in a way where you're not trying to achieve any sort of industry-style recording. Instead, you're recording with people who also don't know what they're doing. It's very low rent. You get these fucking awesome records out of that. That's a great way to use a studio. I'm not dissing recording studios. It's awesome. If you're going to record in a studio, you rock the fuck out and make a lot of noise.

I remember interviewing you, and you said, "I want things to be my way." Then the next record [Tone Soul Evolution] you made with Mike Deming [Tape Op #45], right?

Well, there were two things about that. One is I started to record for my friends like with Jeff [Mangum] and Neutral Milk Hotel and stuff. Also, I didn't know how to use all the equipment like compressors and stuff. And Mike Deming had put out an album with Lilys, Better Can't Make Your Life Better. It was the greatest sounding modern record I'd ever heard. It was incredible. At that time, it was the only record that came out that authentically sounded like a classic record. It's all high-fidelity and stuff. I needed to learn more about recording. I'd always taught myself from childhood. So, I would use compressors and stuff, but I was just doing it by feel. I didn't really know what the knobs were doing. I just closed my eyes and twiddled the knobs. I still do that, but now I know what I'm hearing. I would look at the red light and just be like, "It's flashing. That's good." But it's not always good on the compressor!

Some devices.

It's usually the red light flashing is good. Unless it's your computer. Then it's bad.

I thought that was interesting too that you'd taken a different path to just explore working and collaborating with someone like Mike Deming.

Well, Mike's a recording genius. He's incredible. I needed to learn some of the stuff that he knew. Right after that, I went and recorded with The Olivia Tremor Control. We were recording Tone Soul Evolution, the Apples album, and I recorded In the Aeroplane Over the Sea, and I recorded [The Minders'] Hooray for Tuesday right after that. I needed to be able to get the skills to pull that off. Just knowing how to hook things up and using a patch bay. He taught me how to use a patch bay. He taught me how to use a tape machine with more than eight tracks. He taught me how to use a compressor. It was incredible. Condenser mics, stuff like that. His studio [Studio .45] was a very non-slick studio. It was completely vintage. It was really cool. We recorded to an MCI 24-track. But we also sync'd up my 1/2-inch 8-track Atari with SMPTE, the same one that Martyn [Leaper, The Minders] has. I would go home with a rough mix on that and the SMPTE track, which is inconvenient though, because you had to leave a track between the SMPTE tracks and the other tracks.

It'd make that weird noise.

Does everybody know what SMPTE is? Okay, with tape machines you can print this code to the tape machine. It's kind of like MIDI. It's kind of like a rhythmic-sounding fax machine code if you were to listen to it.

It sounds awful.

Yeah, it sounds awful, terrible. But the point is that you could use this code and send it to some master control box that would be hooked up to all of your tape machines, and it would be like the clock. It would be running all the tape machines off the clock. The tapes would have this code on them, and it would track the code and keep the machines together. It really didn't work that great, but people have been doing it since the '60s or something like that. I think The Beatles developed something like that on Sgt. Pepper's where they had two four-tracks going or something like that.

There's a certain way to synchronize the motors.

Yeah, you're totally right, that's what it is. You override the internal oscillator. That's what it's doing.

This clock is controlling the capstan motor, which is a little metal thing that spins, and the pinch roller holds the tape against it and keeps everything on track. You'll see, if you ever have to lock two tape decks together using SMPTE timecode, you'll see one will have to catch up with the other one, so you'll have to have some extra time at the beginning of the song when you hit record and play or whatever. You'll watch the two tapes go back and forth and finally catch up.

Yeah. Tape machines are really different too, because the tape machine runs at a slightly different speed depending on where in the reel you are. If you're at the beginning of the reel, one side has a lot of tape on it and one side doesn't, then one side is being dragged and the other side is really free to spin. Unless the tape machine's really awesomely calibrated, and you keep it calibrated all the time, it runs slightly differently from different parts of the tape on each machine, and then you're trying to sync up two or more machines like that. It's pretty awesome. I would take the tapes home and do overdubs on the 8-track, and then we'd take them to Michael's studio and SMPTE it up with his 24-track and dump the tracks over there. It worked out great, actually. He was really good at doing that stuff too. That was a cool experience.

He's a good technician.

Yeah, he's great. He's like an audio guru for me. At the time, I really needed him too. It was great. I did want to do it my way, but I had to learn how to do it my way.

I essentially did the same path working with John Baccigaluppi. He's my partner in Tape Op. We'd make records together, and he was the producer and engineer. He'd be like, "Okay, we're going to use this condenser mic on the vocal." "What's that?" I learned all these things by hanging out and watching.

Yeah. You learn to fetishize the right stuff, like Universal Audio and Neumann. I learned to fetishize that before they were companies that you could buy their gear again.

True. Certain things sounded better than others.

Yeah, that's right. You learn what the true junky gear is. That's the most important thing to pick up from other musicians. All of culture is telling you what the cool professional gear is and what the fancy vintage gear is, but there's nobody out there, besides just other musicians and recording people, to tell you what the really awesome shitty gear is. Because that's what you want to populate your studio with, if you want to have a cool studio.

Yeah, if you don't have a ton of money.

Well anyway. And then you want to build it up to have awesome gear that is never quite as good as your really shitty gear was.

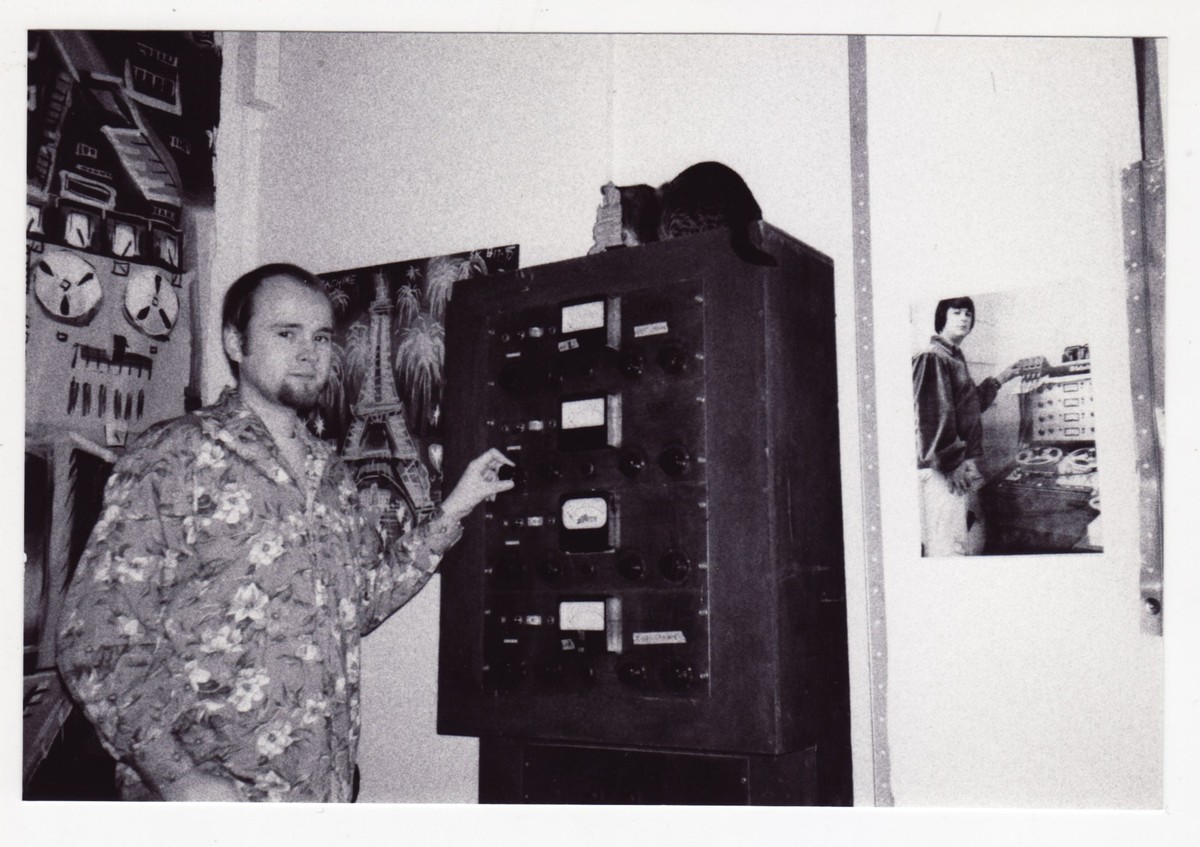

It's kind of a strange path, doing that. I can attest to that with this whole building full of junk here.

That's right. Your gear selection is like the most amazing. Your rack and your console and stuff are so cool. It's amazing.

I mean, this is 20-some odd years at sorting stuff out and figuring out what I don't like.

Just looking around the room, there's all these synthesizers and organs and cool things to play. Oh my god. I love your studio, Larry.

Did you ever go to a professional studio in the later '80s? You'd walk in, and there would be no instruments in there in most places. It'd look like a dentist's office. No instruments. Maybe a piano if you're lucky.

I actually never went to a professional studio until I went to Mike's studio. I'd never been inside a recording studio. Wait, that's not true. I went to Japan to record with Cornelius [Tape Op #69] on Fantasma. They had this really awesome studio where they had a digital tape machine. It was the first time I'd ever recorded on digital. Recording there, it must have been a Fairlight or something like that, this old-school computer terminal. This guy was programming it. It looked like a terminal interface. It was really cool and felt really futuristic. That was really awesome too. Besides that, going to Mike's studio was the first time that I'd ever been to a non-Japanese Cornelius crazy studio.

I forgot about that record! So, in the middle of that you're learning stuff at Mike's and making your record. A 4-track Neutral Milk Hotel record gets made, is that right?

Yes, that's right.

People are still kind of freaking out about it.

Yeah, I guess so. We were trying to make a great album. I'm glad that other people thought so. That's cool.

I think a lot of people did. What do you think it is about the presentation that you helped bring to that too out of Jeff's vision?

For On Avery Island or In the Aeroplane Over the Sea?

Both of them really, to me.

On Avery Island we recorded on a 4-track reel-to-reel. So, I had the 8-track at the time, but Jeff had always recorded on 4-track cassette. We were all really worried about being slick, but he was worried about being slick, and he'd only recorded on 4-track. So, I was thinking, "Well, let's use a reel-to-reel, but it's still 4-tracks. You can be limited to using the same number of tracks as you were using before." He'd record on his 4-track cassette and mix it to a regular stereo cassette deck. Then you could take that and stick it right back into a 4-track. You had two tracks with your mixdown and so on. So, we did that with the album. I think that we mixed it to stereo DAT. That's what I did with Fun Trick Noisemaker too. Maybe we did that with Dusk at Cubist Castle. I can't remember. I recorded to a stereo submix and then put it back on two tracks of 8-track. But by the time we were recording In the Aeroplane Over the Sea and Hooray for Tuesday, I had two 8-tracks in the studio. I could mix from one 8-track down to 4-tracks on the other, so I had a stereo mix of all of the instruments except mono drums and a mono bass track of its own. Then you have four more tracks, and that's like having a 4-track. Then you can do all of that infinite ping-ponging and stuff on that. It sounded really awesome. That was my peak, I think, of my awesome engineering, having the two 8-tracks and bouncing between them. I think on production I improved from there. I was in total control of those tape machines. They were like part of me. It felt really good to do that kind of thing.

You really knew what you were going to get from certain things, how hot you printed, what you would get.

That's right. I knew exactly how to adjust the inputs on both of them. I'd splice tape. So, for The Minders, Hooray for Tuesday, there's a lot of tape splicing going into that on every song. Like the kind of editing you do on a computer now. Not exactly the kind.

A razor blade.

Yeah. And that felt really good too, because you're touching the tape, and it's magnetic, and you're a magnetic thing. Touching tape and interacting with it in all these different ways. You're feeling it and taping it and cutting it and listening back to it. It's a very organic process. It felt really mystical. I really love working with tape machines. That's awesome.

And the proof's in the pudding. A lot of those records are still fun to listen to. I think you did okay.

Thanks dude. I'm working on it.

The one thing I thought was really interesting was earlier, we were talking with The Minders, getting ready to run through the sound check and stuff. They were like, "Should we play 'Hooray for Tuesday'?"

If you play “Hooray for Tuesday,” can I play with you? Are there enough guitars? I played guitar on it, one of the guitars.

We'll throw something together. It's a short song, but at the end there's this kind of magical sound collage thing that goes into it. I think the thing that kept me thinking about it is that when people say, "Oh, this was done at someone's house. It's a homemade production." You think that it's all bare bones. There's no filagree and you're just trying to bash it out. This is not.

It's the opposite! It's like you have time to do whatever you want to do if you're willing to tolerate that it might be lo-fi. The more things you put on there the murkier they sound. Also, that's really all that there is to it. I can't see any other reason you wouldn't want to do it, unless you want crystal clarity. Like Jeff Lynne [Tape Op #92] recording on a 4-track cassette machine, he's like really awesome in the studio! I don't really want to hear him on the 4-track. Actually, I do, I want to hear Jeff Lynne on a 4-track. Actually, I have! The Idle Race.

From way back.

Yeah. That was Jeff Lynne's '60s band before he joined The Move.

It was probably a 4-track studio.

It was definitely 4-track. Well, I don't know what it was, but it sounds like it. That's pretty good too. Okay. Let's get Jeff Lynne here to come in. Can we do that?

I'll call him and see what he's doing. You talk about this stuff and being in control, but did you ever think of it as limitations too? Like, "Oh, but I could have 16-tracks."

Then I bought a 16-track. Okay, and that's a funny story. We had the two 8-tracks going, and I saved up the recording budget for our album The Discovery of a World Inside the Moone, the Apples' [fourth] album. When we would get our budgets from Spin Art, the label that we were on, we would just buy new gear. The studio was our practice space too. It was our band's studio. Some people lived there, like Jim McIntyre lived there. When we would do recording projects, it would just pay for all those costs. We'd have space, Jim's home, and everything was just paid for. The point is that I'd take the entire recording budget and buy gear. I'd seen in this Pro Audio Marketplace magazine – there was this zine that used to come out maybe it was every month. It was classified ads, but it was like an international audio thing. I bought my Neumann from it from Mark Linett [Tape Op #47, #146], Brian Wilson's engineer.

Oh my god.

Yes! So, you'd get Pro Audio Marketplace, and you'd be flipping through. Like, "Oh my god, an LA-3A!" Flip and you'd be like, "Oh my god, that patch bay!" TT cables or whatever. It was like hundreds and hundreds of things. The thing is that it sounds so obvious and unnecessary with the internet, but there was nothing like it without the internet. How are you going to do something like that? How are you going to do anything without the internet? You have a zine. That's what they did.

That's where we got the console and the tape deck in the first iteration of Jackpot!. It was from that zine.

They had a 16-track in L.A. that some studio was selling. It was an Ampex MM 1200. The MM 1200 is a classic tape machine. It's classically fat. It's actually really, really heavy, and really hard for even four people to lift it, but it's classically one of the warmest, grainiest tape machines. I saw that it was available, and we could spend our entire recording budget and buy it. So, we bought this 16-track tape machine from 1973 or something like that. Some weeks later it came. It arrived at our studio. Our studio was in like an abandoned building, so the front of the studio was all boarded up with graffiti and stuff. You had to enter through the alley. The alley was a little parking lot that was fenced in, and there was a duplex that we shared it with. That's where The Minders lived. We had that little back area, that parking lot. It was our little area, and we had this community. This community was closed off from the rest of the world, because in the front it looked like an abandoned building, and in the back, it was a fenced-in little area we had. It was really beautiful and magical.

This is in Denver, [Colorado]?

This is in Denver. While we were recording Hooray for Tuesday, In the Aeroplane Over the Sea, and [The Olivia Tremor Control's] Dusk at Cubist Castle and Black Foliage, and I can't even remember what other stuff I worked on. A lot of albums. It was really amazing. Martyn was recording all of his stuff. In any event, we had to bring the tape machine in through the alley and to the back of the studio, because it was the only entrance to the studio. The tape machine came, and you know how in old cartoons what it might look like if you mail ordered a rhinoceros? What it would come in? It would come in a huge crate, and you'd open it with a crowbar, and the rhinoceros comes charging out. Or maybe it's a boxing kangaroo or whatever. Anyway, it was a huge crate, an old-school wooden crate. We opened it up and there was this beautiful tape machine. That was probably the first professional, maybe the only professional piece of gear I owned. That was a great tape machine. We started recording on it. The very first track I printed on it was a drum track. No, it was bass. I wanted to check, because I heard it was really good for bass. I recorded a bass at 15 ips, and god it sounded so good! Oh man, I just knew it was a great decision. The tape machine sounded great. However, it had a flaw, which I discovered on the third day of using it. It's that every third day that you use the tape machine, it blows out all of the diodes in the transport mechanism, because the tape machine has got motors that are turning the tape machine, and it's an earlier tape machine, so they hadn't really nailed this down yet. The 2-inch tape is very, very heavy. After a couple of days, it's just like, "I'm done!" All the diodes that are antique electronics would blow out. There was an audio repair place in Denver that came in and fixed it, but they were like, "This is going to keep happening. You're going to have to learn to fix it yourself." So, it was really lucky that there was this electronics store right around the corner from our studio. The studio was in this fairly old run-down business district in Denver that I think now is all condos. But there was this old store that had been there since like 1920. Not only had it been there since 1920, but it had backstock going back to 1920! You could get oscilloscopes and stuff, very, very old gear. Literally you could get electronics from any era, just in this old storeroom. It was before the internet, but I'm sure when the internet happened, they sold everything in one day. Eventually we started to buy them out of their diodes. I bought all of their old-stock diodes, so then I had to start finding other places in Denver. Then I had to learn how to replace it with other diodes. The whole thing was a nightmare. In the meantime, I had to learn about electronics. In learning about electronics, I started learning about mathematics and studying it on my own. Then I went to graduate school a few years ago, and last week I defended my Ph.D. dissertation, so it turned out to be okay that the tape machine was breaking down all the time! But it was really good too, because we had the two 8-tracks, and we were recording two records, the Apples were recording. We were recording two records at the same time. On the day the tape machine would work, I'd record on the 16-track, The Discovery of a World Inside the Moone. On the 8-tracks we would record Her Wallpaper Reverie on the off-days, so we had two things going at the same time. Because the tape machine was broken so much, it took two years to record The Discovery of a World Inside the Moone, whereas it took like a year or less to record Her Wallpaper Reverie, so it turned out that came out first. It was cool. It was still productive. Then some years later, Jim McIntyre ended up springing for the repair. You could send in your tape transport block, and there's an upgrade you can do. The ATR, Audio Services thing. Mike Spitz did it. He adjusted it and sent it back. It worked, but then we basically stopped having a studio right after that. So, I gave the tape machine to Bryce Goggin [Tape Op #40].

Speaking of more people you meet along the road.

He's the best.

That was the history here too. We bought a tape deck, and then we had to keep buying these little relays and learn how to clean the relays internally with this tiny file, and then spray stuff on them and put them back in. They'd be sparking and stuff when you were playing tape back. It was crazy.

That does sound crazy!

It was nerve-wracking. Some of the older gear, especially that's been around for a while, things are breaking. It's so fun to have the track width of a 16-track, 2-inch tape deck. It's beautiful.

It sounds incredible. It's its own sound.

But when clients are sitting there and it's not working...

See, that's the difference. I never had clients.

Well, you had friends.

At that point I wasn't even recording other friends. We were just doing our thing. That was cool. It was fine for me. You had a studio. That's much more stressful. Well, it's not stressful. It's a learning experience. It's maybe mildly stressful when you have the greatest drum sound and then the tape machine physically blows up. It would make a loud pop. The tape machine would go, "Boom!" And you'd hear it wind down.

Oh yeah. Last year I went to a studio in L.A. to make a record, and the tape deck stopped rewinding. I had to keep going into the machine room and spinning the reel a little by hand, like you're a DJ.

It has to be this perfect balance. A tape machine is a beautiful machine. It's like when you tune a guitar. Do any of you play guitar? If you tune a guitar so that an E chord sounds good, it's like, "Oh, it sounds beautiful." Then you play a G chord, and you're like, "Oh, the B string's out of tune! Okay, I'll tweak it. Now it sounds really good." Then you play a D chord, and one of the strings is terribly out of tune. You can tune the guitar and get it to where nothing sounds perfect, but all the chords sound pretty good. That's how you play guitar. You get it to that stage, and it sounds pretty good, but it's not perfect. The nature of the guitar, the physical nature of the vibrating strings and such, it's such that the mathematics won't line up. Yeah, it's impossible for a just intonation instrument like a guitar to ever be perfectly in tune, so you just have to make it a balance. Apparently, a tape machine is also tuned to just intonation. You can never quite get all those oscillating things to tune up. They're just like guitar strings. There's something of a balance.

Did you eventually start not using tape, like for later recordings? Did you start using Pro Tools along the way?

I just use whatever. Sometimes I'll record on a boom box and sometimes I'll record on a computer. The computer's really easy to record on. I like to use 4-track. I just recorded a 7-inch with my band Air-sea Dolphin on 4-track, and it's great. I love working on 4-track. I think that when I record with the Apples, we usually record off of tape, going live off the repro head into the computer. So, the basic tracks are recorded on tape. I think it just depends on the sound you want out of the project or whatever. Let's see, when was this? 1998 or '99. I had an oscilloscope between the speakers where you'd now have a computer monitor, so I'd watch the oscilloscope pattern and stuff. It's very psychedelic to look at an oscilloscope and watch your music go through it. It's basically like a galaxy that's flowing and ebbing. It's doing it with your music, and you're so in touch with your music. You're hearing this thing and seeing this thing, and it looks like retro vector graphics or something like that. It's very, very cool. Anyway, I got a computer, and I put it off to the side. Of course, there's the oscilloscope there, because that's where that would go, and I felt uncomfortable with the computer. I had previously been under the belief that digital recording would suck the soul out of the music in some sort of spiritual way. That's totally not true. The soul is from you and your instruments. It's not from your computer or the recording device. Any recording device is fine. Do you have to paint onto canvas, or can you do it on wood? It doesn't matter. But I got a computer, and it was really, really useful. When we were transferring between the 8-tracks (this is how I use the computer in my studio). I would mix down from the 8-track to the other 8-track, but I'd mix down to four tracks. Then I'd mix those into the computer so I could edit them. Then I'd put them to the other 8-track and keep recording. The computer was like this middle place. I didn't trust that a hard drive would be a physical object that could play music in the same linear, time sort of way that I felt like I wanted to hear it. I wanted to see something spinning when I heard music. A record, a tape, something. A CD. I just wanted to imagine there was something. I mean, a hard drive's spinning too, but you can't see it. It's very abstract. What's going on in there?

And then it breaks.

Yeah, and then it breaks. I mean god, recording on computer's amazing, actually. When we were recording Tone Soul Evolution at Mike Deming's studio, he had been wiping some tape clean. Then we put on the tape reel to work on Hilarie [Sidney's] song. You were playing it earlier, actually. I think it was “Silver Chain." Mike had all the tracks on record, because he was cleaning the previous tape. When we went to record, he was looking at the console, not the tape machine. When he hit record to do the next track, to start it, it was just running and there was no music. We're sitting there, and it's like, where's the music? Click, then through the talkback mic, it's like, “Oh fuck.”

He wiped it out?

He'd just recorded over a huge bit of it. This is like elaborate horn arrangements and guitars and sound effects, and this huge production. We'd done all the SMPTE stuff and gotten it bounced off of 8-tracks successfully. So, Mike was like, "No problem." He knew a guy four hours away in Massachusetts. We were recording in Hartford, Connecticut. If you're driving through Hartford, as you're going through the downtown area, on the left hand side of the highway, if you're going north, away from the city, there's a big-ass old factory. It's a huge old factory. It has a spire on the top, like a painted sort of spire that might be on a mosque or Freemason's sort of temple or something like that. That's where we recorded that album. It was a Colt .45 factory.

That's where they made guns, and they made music.

Yeah. So, we drove to Massachusetts. He knew a guy who had a Fairlight computer in his studio. The Fairlight was like an early version of Pro Tools, going back to like the late '70s. This was incredible. There was another passage of music that had the same instrumentation on the tape. I don't know how he did this, because we didn't record to a click track or anything, but he dumped all 24 tracks of the other passage into his computer, and the computer was also hooked up with SMPTE and stuff to the tape machine, so the computer was running the tape machine. I don't know how he did this, but he punched in all the tracks onto the tape machine, punched them in into the gap that had been recorded over, and it lined up perfectly. I don't know how he did it, but this was like a miracle. I was sold. Also, Park Peters was an engineer in Denver who used to master all of our records, and he taught me about mastering. He also would use a computer to master. I was pro-computer from the start. You can also do edits and crossfades, very experimental stuff with the computer that you can do to some degree with a tape machine, but a lot of it you can't do. You can't with the tape machine take the bass drum and move it to a different part of the song and onto a different track. You can't do that with the tape machine. That's the problem. You could move everything around just like you were moving around pieces of a game with a computer. It's a different thing, and it's really awesome. They're both awesome. With a computer, you can't take a razor blade and cut it and paste it back together with your hands and touch the magnetic material and absorb and somehow interact in an electromagnetic way with your music.

Even today if I do a real razor blade tape edit in front of the client, they're just amazed that you'd even know how to do it. It's like a lost art.

It's really primitive-looking when you do it too. It's terrifying.

You're scrubbing the tape, listening for the kick drum. Okay, right there. Mark it with a China pencil, cut it with the razor blade, get the blue tape off, cut the other part, and stick them together.

Let's just explain this really fast for people who have not done it so we can.

We can go in the other room and do a demo.

Can we do that? So, if you want to splice tape, you've got to splice it at a place where there's a sibilance or like a white noise kind of sound or something, so like a kick drum or a snare drum. Something that doesn't really have a pitch to it. It's possible that there will be an artifact at the tape splice, but the artifact is not like a computer splice. When you do a splice on the computer, if it doesn't work out, there's this horrible tick. The tick is in the high end above the music. It's so present. The tape machine's not like that. When you cut tape and paste it back together, the magnetic particles are literally reaching across the gap where the tape was. It's meant to mend itself, just like your skin mends itself when you get cut. We're not talking about just cutting something and it's done. We're talking about putting something together and it heals. You can hear that.

It'll sound better the next day.

It will. It'll sound better. You don't hear the same kind of edit mistakes that you would with a tape machine. Even so, there's some possibility of their being a little sound or something like that. If you are going to have that you want to be on a kick drum or something where it's already got that kind of a timbre. So, you want to splice, find a kick drum hit or something with a sharp attack, quick sound, and then you turn off the tape machine's motors if you have the play head engaged. You're just rocking the tape back and forth like a DJ scratching records. It feels so good to do it.

It makes everyone in the room laugh.

It's a very funny sound. Then you locate that point and take this little blue grease pencil, and you mark right across. You draw on the record head. Your tape is on the head, and you can see the magnets on the record head lining up, going down like a guitar pickup. You draw a line right down there, and that's where you're going to splice it, right down that blue line.

Make sure you've selected the same head you're making the mark on. If you're listening from the repro head and you mark it on the other head... I did that once. Cut off the beginning of the song.

So, you splice it two inches later.

Yeah, it just removed the kick drum downbeat in the beginning of a Richmond Fontaine song, for anyone who knows. If anyone ever went back to the master tape of that...

Was it good or bad?

Well, we kept the previous mix. Not the one I was trying to clean up the beginning of.

And to wrap up our lesson, the rest you just go by feel. Got some tape? You know what to do with it.

Just tape stuff up.

It can look really junky too, like your cut can look kinda junky, because you've probably used your razor blade a thousand times. The tape can look all crappy, like maybe it didn't go on perfectly. It's wrinkled like you didn't wrap a present right, but even so it just sounds perfect and beautiful and heals itself.

Sometimes.

Okay, yeah. This goes back to being able to tolerate low-fidelity content in your music. The more low-fidelity content you can tolerate, the more that you don't mind hearing the tape splice.

True. The amazing thing about making records to me is that meticulous little creative things can be done with a computer. If I do a little tape splice and it sounds a little wacky, someone might go, "I dunno man. I think you ruined the record." Then if you go listen to “Strawberry Fields Forever” by The Beatles, it's got one of the weirdest most egregious tape splices.

You hear that splice.

You've heard that splice your entire life. You might not hear it anymore, because you're used to it.

It's its own effect. You can do a splice because you want that effect. When we were doing “Hooray for Tuesday”, we were wanting to hear the splice sometimes. You want to hear it. That's the tape splice effect. You get it by splicing tape.

There's no other way.

That's right. But you were asking about the computer thing. I've always been pro-computer, but I also have this like quasi-metaphysical belief that using digital will suck the soul out of the music if that's the final end place for it, which I don't believe at all. It's total bullshit. But it doesn't matter what you make music onto. What matters is the music you're making and the sounds you're making. It doesn't matter if you use a shitty mic or what you're recording onto. If you want it to sound hi-fi, then record on hi-fi gear, but the thing that matters is that you're putting down an exciting, interesting, and fun vibe that feels like something to you and you think your friends will like it or that it'll resonate with them. That's all that really matters. Nothing else really matters about recording besides that. You can do that with a handheld tape deck. That's great, like the flat old-school kind. Anything's great to record. You can make a great-sounding recording that's indistinguishable from one that's made really fancy, because everybody assumes you went to all this trouble to make a great recording sound like that even if it's recorded on a handheld tape deck or whatever.

I get these weird things where I'll be mixing with someone, and they recorded everything really pristine through a computer interface, and then they go, “Can you just do something to kind of lo-fi it up?” I'm always like, "If that's what you wanted, you should have started with that sound!" I get kind of irritated, because I feel like lo-fi is like this concept of a sound as opposed to a necessity in certain ways. Like if you want that sound, start by getting that sound at the beginning. It's really odd to me to sort of apply a patina.

Yeah, I know what you're saying. But still, you can. Just dump it to a 4-track and it sounds that way.

I know. I've got my 4-track cassette out there. We should just start doing that.

I love using computers. I really don't feel like I have a bias toward any particular recording medium. You use the thing that gets the sound you want if you want to have a particular sound. If you just want to have something that feels good, you use whatever's there.

Did you have time to record working on a Ph.D.? Have you had time to play music?

I have a band with some friends of mine in Atlanta called Air-sea Dolphin. We've recorded a couple of 7-inches. I've recorded a 7-inch with my friend Will Hart [The Olivia Tremor Control]. That's the only thing I've really done in the last few years. It's been hard. There was just no time with graduate school. For four years I didn't play guitar at all. I didn't even think about it. I wasn't able to do a lot of mathematics by being a musician-type, and I was just so glad to be spending all my time doing mathematics. It was awesome. But after some years, I started to feel not complete or something like that. My friend John Ferguson and I went on tour opening for Neutral Milk Hotel a few years ago, the same one that The Minders opened up for. In fact, we played a show in Seattle together with The Minders. My fingers were like… I had no callouses. I was playing acoustic guitar, and my fingers had these gashes every night. I'd show them off to the audience and everybody would gasp! So, I didn't let that happen again. I mean, I didn't practice. I thought about what I would play a little bit. I made a list of songs in advance that I can choose from. But no, I don't like to practice for shows. I think that every time I play a song I want to just feel it and be inside it. I'm not too worried about being good. I mean, I'm sorry. I want to be good. I'm just not worried about getting anything right, that's all I'm saying. I wrote the song, my fingers know how to play it, I hope. I always like to play songs that I either haven't played ever or for a long time, so I'll probably try to throw in some songs, but I'm not sure. We'll see how it goes as we go along. Thank you so much for having me here!

Just one last question. Since we do have The Minders playing here as well, do you have any memories or thoughts or stuff about making that record, Hooray for Tuesday?

We recorded together almost every day for years. I have a lot of memories. I have "tricky audio things that I did" type memories, and I have "personal" type memories. We had that parking lot area, and I can remember going out there to work out harmonies for songs like “Hooray for Tuesday” and other songs on the album out in the parking lot, because we shared it. The Minders had their house, and we had our studio, so we'd go sit out in the parking lot. We had benches and chairs and would sit on our cars and stuff. Working out the harmonies was a very precious memory, us all singing those parts together and hearing them come together. It was really great. I think that's one of my favorite memories of recording that record, just us sitting out and being together as friends in the parking lot area that we had behind our studio in the alley. The way that I had recorded the drums on the album, I like to record with a three mic setup usually, so I'd have an overhead mic, one mic on the snare drum, and one mic on the bass drum. I have a fancy trick on the snare drum. I'm going to tell you how I record the snare drum. This is the way I've always recorded the snare drum, and it's the best snare drum sound. I worked it out on one of the first Apples 7-inches I did. The first time I used a 4-track reel-to-reel, I discovered this great way to mic the snare drum. You use a [Shure] SM57, and you point it not at the top or the bottom of the snare drum, which are the usual places, but like straight at the side. The side of the snare drum's there, and you put the mic there, just far away enough so that the snare doesn't hit it every time the drummer hits it. You put it coming from the outside of the set, so it's pointing inward at the drummer, and below the hi-hat, so the cone of sound is coming down. It's the perfect snare drum sound. If you want the perfect snare drum sound then do that. Also, it's a great drum sound. The whole drum set comes through the snare drum, and it sounds really great that way. Then I'd have another mic hanging down from above that would be probably a Neumann U 87. I put it at eye level for the drummer, facing directly at the kick drum pedal. That to me is the perfect place for the overhead. It's at eye level for the drummer, or slightly higher if they're wild like Jeremy [Barnes] in Neutral Milk Hotel, and they're going to whack your U 87. By the way, my U 87 has tons of nicks in it, and up to some point, I think they made it sound better. Every time I recognized it got hit by a drummer, it would sound better, but then the insides of it shattered like an egg. My friend Tyler [Petito] at Acorn Amplifiers in Atlanta, who's this electronics genius that I know, he pieced it together, glued it together, and fixed the insides of the microphone, because it had shattered like an egg. Now it works again!

Yikes.

But anyway, that's my sound for recording an overhead. A single overhead hanging down, diaphragm at eye level and pointing at the kick drum pedal. It's low enough that…

Directly in front of the drummer's face?

Directly in front of their face, pointing at the kick drum pedal, wherever that is. The thing is that the cymbals are really, really loud on the overhead, but when you hit a cymbal, it's not just sending the sound out in a sphere. It's rocking, and it's kind of sending the sound out in a cone that goes like that. You have this cone like this. There's a cymbal here and a cymbal there, and the cones are going upward. If you put the mic right there, it's underneath all the cones of the cymbals. What you're picking up from the cymbals isn't this clang or other weird resonances, but you're picking up the thing that sounds awesome, that splashy, crashy sound of the cymbals. That's where I always put the overhead microphone. Then the kick drum I just point at the front head and angle it a little bit, put it like an inch away or something like that so that it's across from the kick drum pedal, through the drum though. Not stuck inside there. It sounds really good on the front head. That's how I'd record it. However, I was still working that technique out at the time. I hadn't discovered anything about putting the mic low, so I had the mic up higher, because conceptually I thought it would get more of a room sound. The sound of that studio sounds terrible. We had to hang blankets all over the place and stuff to get it to sound reasonably good.

To gate it.

Yeah, we gated it. The drums on one of the songs on Hooray for Tuesday were really cymbal heavy. I really wanted the snare drum to pop out like on Sgt. Pepper's or something like that. We had this great snare drum sound. The overhead cymbals were too loud. I took the drum track, and I ran it through two tracks on my console. I had this Neotek console, a Series III. I still have it. A friend of mine has it in his studio in Lexington, Kentucky. I ran it through two of the tracks, and on one of the tracks, I tuned the EQ to the frequency where the cymbals were the most glaringly crashy and splashy in. And I turned the EQ all the way up, just to 10. You were hearing this clanging so loud that it was ear-piercing. Then I cut the other frequencies. Then I put it out of phase, and I brought it in underneath the snare drum track. You could bring it in to a certain point to where it would perfectly cancel out the clanging of the cymbals and the snare drum would pop through. It was magic. It would only happen at a certain point. Phase cancellation is like that. If you went past that point, suddenly the cymbals were all clangy again. But you could do it perfectly. This is a good trick to do if you need to. Put the two channels out of phase, boost the undesirable frequency horribly on one of the channels, and then you just feed it in from zero. Listen carefully, and you'll hear the thing you don't want to hear go away. It's really cool. And on top of that it has this really cool phase-shifty sound that's kind of psychedelic. So, it's not just a good audio trick. It's actually a cool effect. If you listen to that song on Hooray for Tuesday, you'll hear the drums kind of sound like they have a phase going through it. That's because I was feeding it in. I felt really clever about that. In fact, phase cancellation is like this really magical thing.

It's very mathematical.

A very mathematical thing that's inside sound. You can take two tracks and have two songs that are totally different songs. But maybe you have some of the same sound effects. Let me see, no, actually I don't want to give away my trick. I haven't used it yet. Taking it back. I have a cool trick for embedding songs inside other songs inside other songs and so on. You can combine them in certain ways and have them all cancel out to get to the different layers, and it works really well.