What's the name of your new record?

It's called Creatures of the Late Afternoon. I'm a fan of B movies like, Creature from the Black Lagoon, all the lo-fi B movies from back in the day. I love the artwork and the aesthetic from all that.

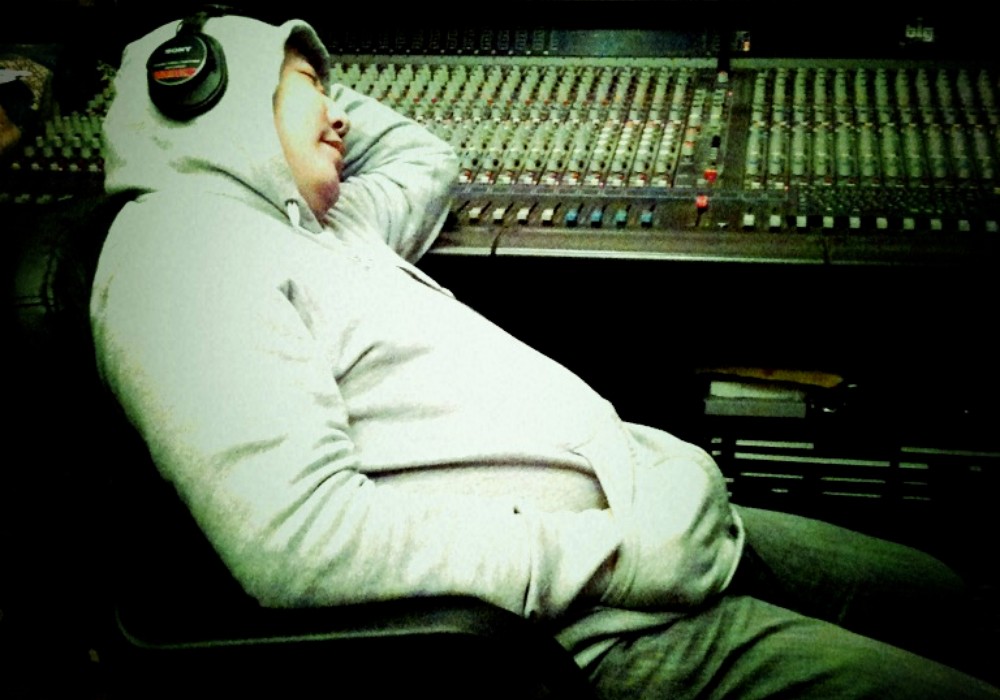

So, that was a title that I had in my mind for many years. I didn't know what it meant until during the pandemic when I was working on this record, and it finally congealed. The other [reason] is often the best writing work happens in the afterhours. I don't think I've ever kept much that I recorded earlier than midnight, which just means the whole circadian rhythm gets pushed. Even if I'm awake early in the morning, driving the kids to school or whatever, it's like my brain doesn't really operate until the late afternoon.

So, you started this during Covid?

Yeah. I didn't quite know what it was, at the start. I had this loose concept of these creatures. I was watching a lot of nature documentaries with my younger daughter, and we were learning about all these amazing animals all over the world. Then I started painting creatures with my daughter. Of course, I'm a studio nerd, so I would start painting them with musical instruments in their hands or in their claws. Then it started to mix. I’d think, "We learned about the mantis shrimp last night. What would it be like if it was playing drums or on a [E-mu] SP-1200?" It was this imaginary thing; my version of The Muppet Show. You remember Dr. Teeth [and the Electric Mayhem] with Animal on the drums?

Of course.

It was wicked. So, I expanded that to include crustaceans and other animals. I was painting, and I was letting it go into modular synth and Theremins that I wanted these creatures to play.

When you had that in your brain, what does it inform? What do you reach for first to start to get an idea down?

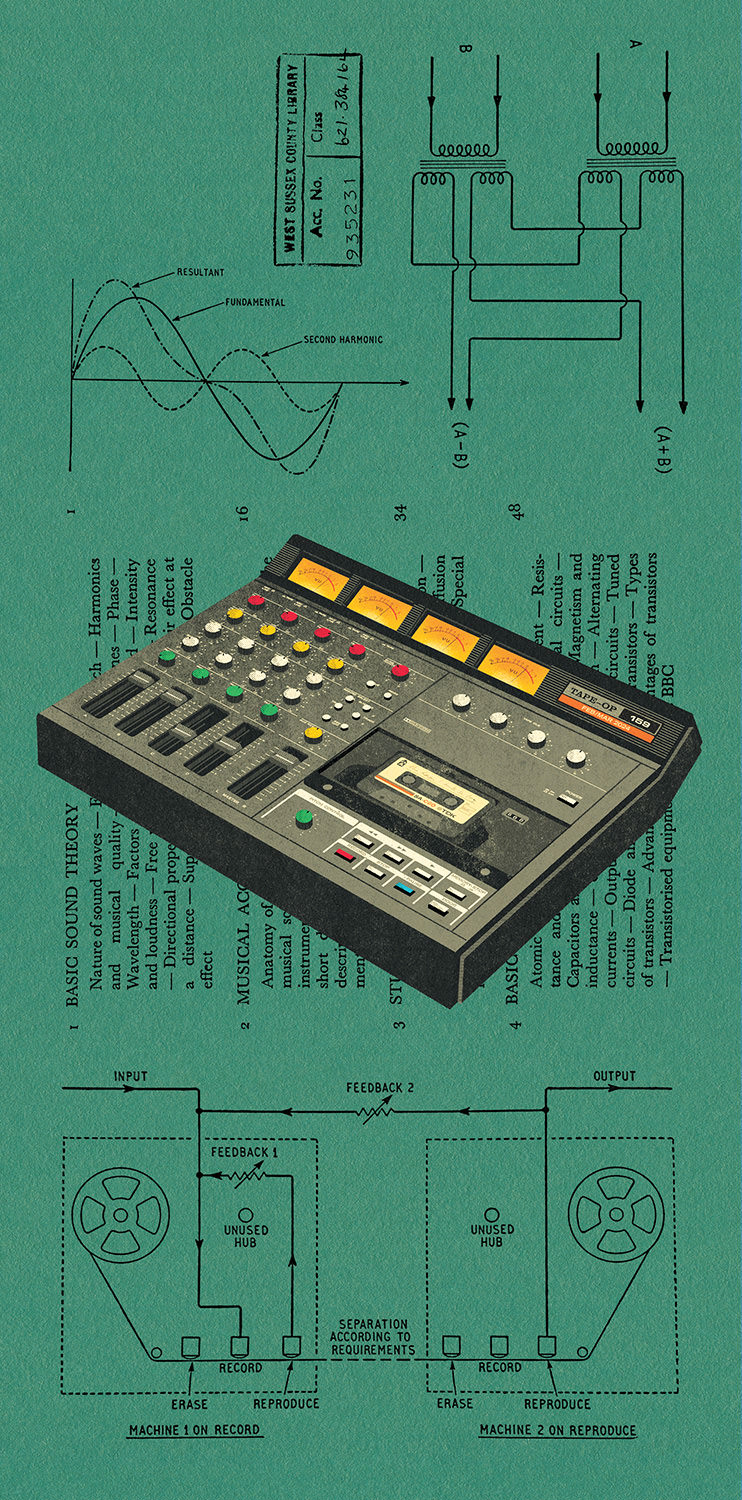

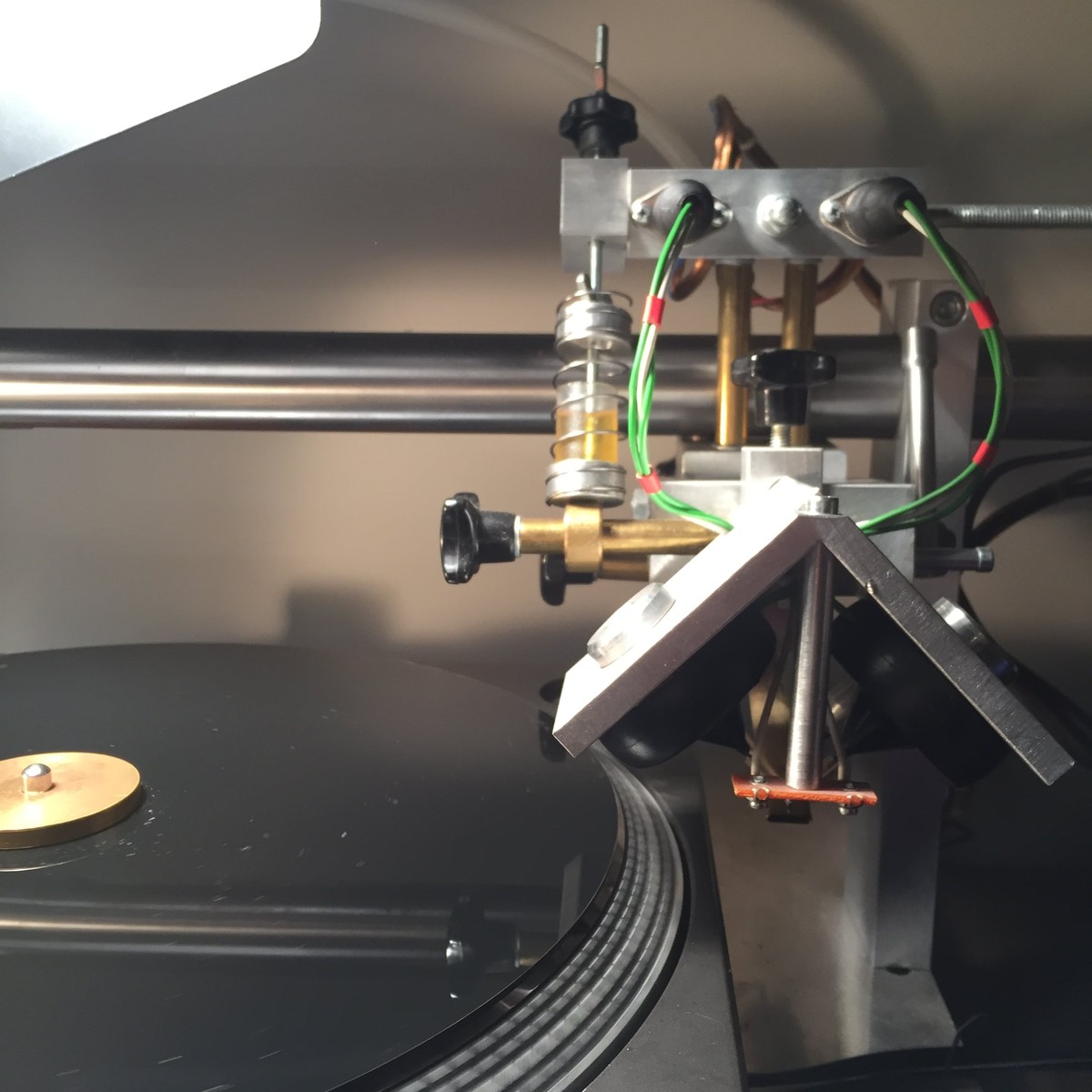

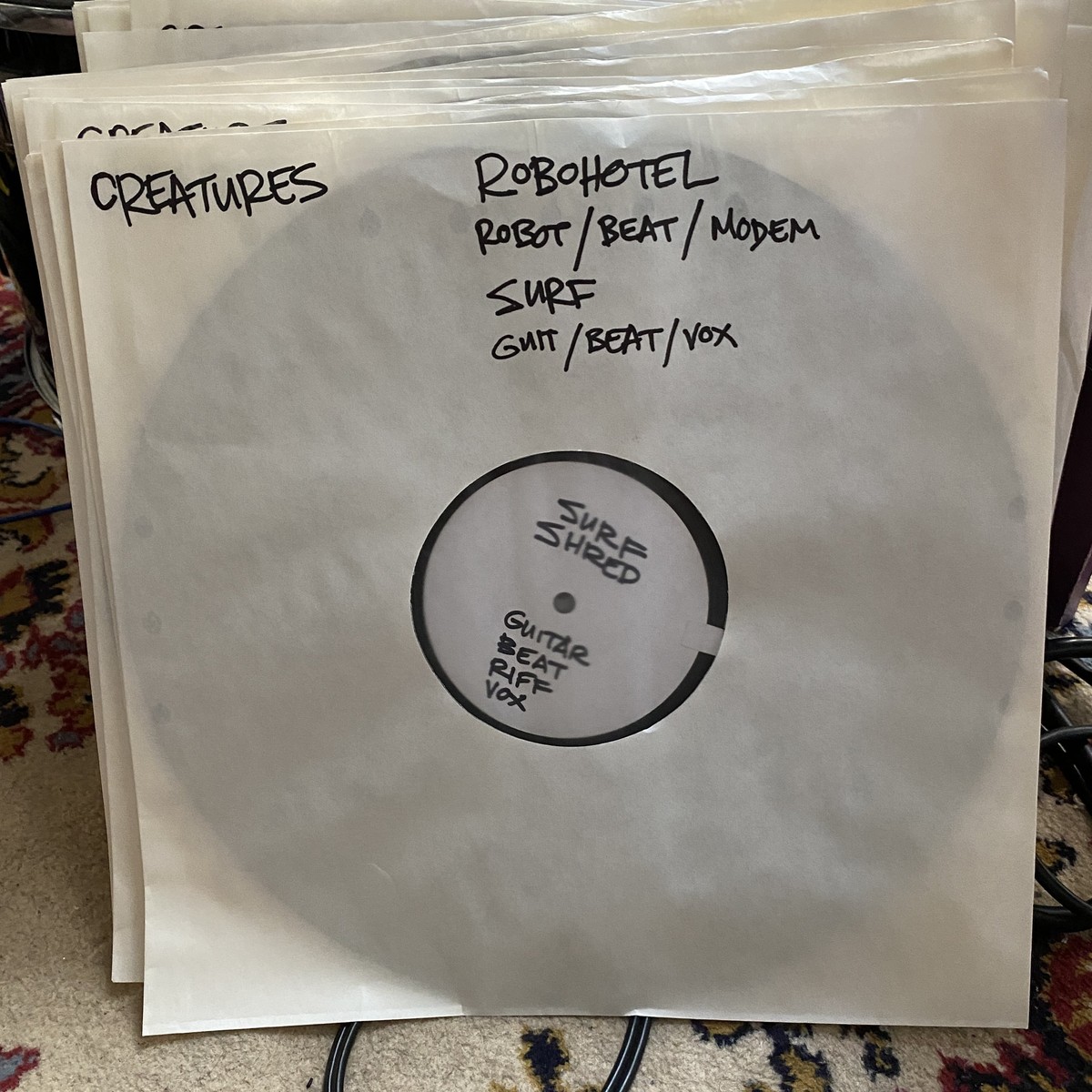

It was lockdown. I couldn't have my buddies over, but I had these paintings. I had this painting of a sloth on a Fender bass, and I was staring at the painting. Then I walked over [to] the studio – right next to the workshop where the paintings were – and I said, "What would that sloth sound like?" It has really long arms. It's a sloth, so maybe it slides really slowly between the frets. Sloths have these long claws, so I said, "Oh, that probably sounds like a slide." So, then I was playing slide fuzz Fender bass to try to inhabit what that creature would sound like. That was the first step, playing around and seeing what tones would come out. Eventually, a bassline might come to me. I was recording all this, so a lot of those sounds ended up being the source material that I would use on the tracks. I have a record cutter in the studio, and I would cut those stems individually to vinyl and then that would be the palette that I would use. I wanted to create everything in the studio. I played over 20 different instruments. Often, I would start on the piano, because that's my first instrument, and then I would map out the chords in the form (verse, chorus, bridge), and then add layers on all the other instruments. Then I’d solo all the stems and cut each stem to vinyl. I could have released it like that, and it would’ve sounded like a one-person band or a bedroom studio album. But once it was on vinyl, I had a chance to rewrite a lot of the parts. If I had a five-note guitar line on vinyl, I knew I could stutter the second note or spin back to the first note on the turntable, do a little pickup scratch, and rephrase it. But I still had all the core harmonic content that I wanted in that section. That part was fun.

Was this always over the original form? You would take the stems, work within the same session, and lay it on top of where the form already existed in a session?

Yeah, sometimes. Or I would record synth to cassette – goof off and trance out into some weird drone – and maybe cut that whole thing to five minutes of a side of a record, then drop the needle and try to add it as another layer. But, for the most part, the tracks that sound more like "traditional songs" I would stay in the same session and proceed to replace everything with the turntable-ized [versions].

So, not raw building blocks that you then used to create a song from scratch with a drum cut, a guitar cut, or a bass cut?

Yeah, but I would take the drum part and cut it to two pieces of vinyl and then beat juggle between. You'd have to listen pretty closely to catch where it's happening. Sometimes I kept the groove, so it might be once every eight bars or something. You just hear the pickup scratch or get this different energy. It gave it that b-boy energy on some of the tracks.

That's the part that I couldn't figure out. It makes sense that all the layers were able to be manipulated individually. The way it's stacked up is brilliant.

While I was working on this record – and the concept of these creatures banding together and making all this music – this narrative was starting to form about a full story. And that has now congealed to be the next stage production we're going to do, in the tradition of Nufonia Must Fall and The Storyville Mosquito. The third one will be Creatures of Late Afternoon. I realized this record can serve as the soundtrack for this upcoming three-act live film. And once that clicked in, it started to become a strong muse that flowed into the whole collection of tracks.

Do you feel like it's simpler for you to invent a world, because then, in that world, there is this version of, “This is 'right,’ and this is 'wrong?’" Do you find that you'll make moves musically, in service of that?

Absolutely. I was raised on The Muppet Show. It's part of my DNA, where I feel that's allowed and it guides me. It's different than, "I wrote a few poems, picked up an acoustic guitar, and I decided to iterate this poem into song." I'm not that kind of artist. To me, it's always been a little bit about the visual and the narrative aspect. Growing up, my first records were always storybook records. So, even if there was music, there were also sound effects, a narrator, a story, and there were visuals – a read along book. When I'm in the studio making "a record," I can't separate that in my mind from a narrative or a story or characters.

Did that world exist in your brain before you brought it to life? Was Nufonia… the first one that gave us a vision into what was in your brain while you were making the music?

Yeah. Nufonia… started with the book. I got a book deal, and I wrote this graphic novel, which isn't what the publisher asked for. They asked for a hundred page, 10,000 words about any topic. I wrote them a 350 page, no words, romance story about a robot trying to write love songs, but they liked it. I remember delivering the manuscript three years later, knowing full well that they might want their advance back. It was Emma McKay, who worked at the publisher [ECW Press] at the time, who said, "There's this theme of this robot writing this love song in this story. What does that sound like? Maybe we can record it and include it with the book on a flexi disc or a CD." She was the first one who pushed me into scoring my own story idea, 20 years ago. Since then, it's become something I keep doing.

Did you already have a narrative in your brain for your earlier records?

Yeah. I find it starts to make more sense to me. I don't know if it makes sense to other people! In the case of this album, those creatures became kind of spirit guides. The tracks started to work towards their story. But it also comes from real life. There's one track called, "When U Say Love," which is a '50s or '60s jukebox vocal group-type track that came from real life. For your readers, they’ll be interested to know there's a Fairchild Model 658 [Reverbatron] on that. I was like, "Oh, this is of that era." I had a… What is it called? A music master mix or…

[MicMix] Master Room spring reverb?

I tried that one and it was a little too dark, but then I tried the Fairchild 658, and it was super noisy, but it worked. Like a garage band from the '50s. Some of the drums and some of the vocals would go through that. By that, I mean from turntables. I recorded the drums pretty dry. I don't have a big reverby room, but I remember using an Altec 639 [microphone] to record the whole kit from afar to get that blendy sound. I put it through a Digitech Drop pedal and lowered it a couple semitones. It was in real time, almost like doing a low bitrate pitch shift down. I gave it this boomy, sampled sound to begin with. I cut that to vinyl and then juggled it back and forth through the vinyl. Sometimes I would record the turntables direct, but often I would put them in another room. There's a little bathroom near my studio, and I had a Fender PA tower in there. It's a small bathroom, but it reverbed all over the place. I probably wasn't doing it correctly, but it was getting some sort of vibe. I threw it in there with the [Shure SM]57 and caught it scratching in it live.

Would you switch actual recording methods to try to bring out whatever you're trying to say emotionally with each track?

Absolutely. On a track like, "The Cards," I remember I was playing around with the [E-mu] Emulator II and the types of tones they were using on [New Order's] "Blue Monday" – some of the bass arpeggiation. I thought it'd be fun to make this '80s new wavy New Order thing, but with turntables. I cut that to vinyl, two copies, and then I puzzled it together afterwards on turntables, which obviously takes it down a notch in fidelity and makes it crunchier. I still wanted that hand cut push and pull. I didn't want it to be this sequenced track in the middle of the record. I was trying to hit these moods and funny moments, like "Pa$SwErdD." It's a heist scene where the creatures have to try to break into this vault and they're forgetting the password, which was something from real life.

With the amount that you're manipulating a lacquer, it's bound to get burned-out pretty quick.

Oh, no. Actually, my record cutter is called Vinyl Recorder from Germany, and it cuts one at a time. It's not a lacquer; it cuts to blank PVC disks and it's a harder material. It can cut six dB louder than commercial vinyl, so that's why I can use those at shows. Even on the last Deltron 3030 tour, for a lot of the parts I would use that and make one or two copies that I needed.

What's your role in Deltron 3030?

I do the turntables. I'm that guy.

Are you a part of the writing process?

Well, Del [Del the Funky Homosapien, aka Teren Delvon Jones] obviously does the lyrics. Dan [Dan the Automator, aka Dan Nakamura] is the producer/director. He usually will bring me in on the last step for that extra spice, or sometimes to provide some harmonic counterpoint on the turntables or some other sound effects, and then to [perform] live. I'm dealing with whatever the track requires. Other times, it's a frantic percussive turntable outro or it's moody, ambient parts underneath the verses.

Does any of that involvement influence the way that you work with those guys?

Yeah, absolutely. Not just Deltron 3030, but touring with Money Mark, Bullfrog, or bands that I was in college with, it was trying to find a way for the turntable part to support what the mood of the song was. I remember being on tour with Money Mark. He'd have a left field instrumental jam with him on a Moog Realistic [Concertmate MG-1] synth. But then there'd be other times on a tune like "Cry," which is just him on Hammond organ and singing this very delicate song. He’d ask, "Can you find something to do on turntables that doesn't become a sideshow bit?" That changed the way I had to approach playing. I’d take the role of a backup singer or a keyboardist, or something rather than just playing lead turntable on everything. Deltron 3030 is also similarly cinematic, in terms of how Del writes the lyrics. It's so evocative and visual, so I'm using turntables as almost a sound design in places.

It's not what people think when they think of a DJ. It's hard to pin down the usage of a turntable on this record.

I've always liked the surreality of turntables. I believe it's a chameleon of an instrument, and that it can fit in many different contexts, but sometimes I would want the part to fit and work and lift in a nostalgic way. For instance, Money Mark bought me a box set of the making of Pet Sounds [The Beach Boys' The Pet Sounds Sessions] back in '96 or '98. We were on the Hello Nasty tour with the Beastie Boys. I listened to the album over and over. All the other discs in that box set are multiple takes of a cappella or slowly adding one or two percussion parts, as well as instrumental stripped-down versions. I was hearing things that I felt in the final album, but now I could hear them clearly on their own because I was seeing what the process was. When I was reading about Brian Wilson and Pet Sounds, he was talking about Phil Spector's "wall of sound" and trying to make a new tone. Saying a baritone guitar meeting a harpsichord and playing the same line, all of a sudden it doesn't sound like either instrument. It sounds like this new thing. I could relate to that concept, in terms of how stacking layers of sound is the basis of how I always approach turntables. Didn't the Beach Boys only have four tracks?

A limited track count, for sure.

Take the whole thing and then crush it down to one track. To hear these different takes of instrumental versions, I was like, "Oh, that's what that the harmony sounded like." Or what that guitar harpsichord hybrid instrument sounded like if you had a chance to dig it out of the mix and focus on it. But I still respond to that record, as a whole. Even the mono version. That was revealing and inspiring for me. On the track "'Til We Meet Again," at the end, I was like, "It'd be cool to have these lift-y vocal harmonies.” I was playing around with mics and reverb, just studying. I know this record doesn't come close to Pet Sounds, but in terms of studio experimentation I wanted to see if I could take the turntables there. It might have been four parts of harmony being sung, then put through a reverb, and then recording back through [the] RCA [Type] 77 [DX ribbon mic]. But, for instance, those back harmonies on that track were just "throw it in and just let it play." Maybe transform it on the cross fade for a bit. And then, at the end, just echo it out by hand. That's not actually a choir, but it sounds like a sample of one. It was fun. With the track "Rise of the Tardigrades," I had been in the National Music Centre in Calgary, [Canada], many years ago.

You were posting pictures every day from that. Every synth in the universe is there.

And people and estates donate more. They have prototype keyboards that never made it to market. One thing they have is the Rolling Stones [Mobile Studio] recording truck. They parked it in the building, and it's a working recording truck. I was working on some stuff, trying to play around with those Helios compressors. It was like, "Wow, this thing just sounds meaner." I remember going up to this other studio they have in the building, which has all this fancy gear in there. We were trying the drums through all that, and they could tell, "You want to go back down to the truck, don't you?" I'm like, "Yeah!" I know part of it is just fetishizing what maybe that component does. I finally found a mono version of the Helios. It's an ADR [Audio Design & Recording] F600 [compressor/limiter], because they were making the compressors for Helios at the time. I found one, and that was the thing with "Tardigrades." I just didn't want to beat and smash it into there. It was more like a kick/snare on a turntable, but just the way it squishes it.

How much were you tracking at the National Music Centre rather than reprocessing parts you had already recorded?

In the synth room I was adding synth layers, tracking to the Music to Draw To album that I was working on at the time. I was playing a Waldorf Wave. They had this weird Canadian brand synth that never got off the ground, and I was playing that.

And what's the takeaway from it, process-wise? What's at the core of why you made this new record?

I think the lockdown, and the fact that all the live shows got wiped off the schedule for three years, allowed me to have this lab time. To try things that I always thought it'd be fun to try, but I'd never got around to wiring up the studio in a certain way to make it happen. On every one of those tracks I was trying to learn something. I was trying to figure out how some of the gear interacts with the others. I hope people have fun with it.

I wanted the vinyl to be interactive, so it comes packaged with a board game, and has inserts for 150 game cards. You travel around the board trying to meet these creatures and produce them as a band. You need a vocalist, a bassist, and a drummer. You'll need some studio time, so you need to get a studio timecard. You need to get an instrument and a recording device, which you can find at the flea market on the board. The last thing you need is a song, genre, and inspiration. There are some whammy spaces on the game where something bad happens, like your tour van gets a flat tire. You lose something, but then you gain life experience, and then life experience cards are your inspiration for songs. I can't wait for you to play with your family.Yeah, man!

I did the paintings of the creatures. My wife, Corinne Merrell, did the layout, the cards, and how everything fit on the center stickers. For the cover of the album, she actually built the two-foot-tall buildings, and I did the lettering of the title. Instead of it just being a storage for the album's songs, there are locked grooves at the ends of each side. You can play the album and then, after four or five songs, each side will lock in silence. After the locked groove, there are hidden board game tracks. There are eight altogether, and they're used as timers and little soundtrack moments for the game. During the matching part of the game, you play that track instead of having a little egg timer. It's almost like the Jeopardy timer, only it's funkier. There's this one part where you can challenge another player to a staring contest, but I thought it'd be funny if, during the staring contest, there was weird, mysterious droney music playing. We had a lot of fun play-testing the game with our daughters, and then with friends. We think people will get a little kick out of it, laugh a bit, and learn about the studio process.