In 1973, Alhaji Bai Konte's record, Kora Melodies From The Republic Of The Gambia, West Africa, was the first album of kora music to be released internationally. Though mostly found in western Africa, the 21-string instrument has gone on to become a sonic signature for the entire continent. Marc Pevar and his wife, Susan Pevar, share the story of how this groundbreaking record came to be.

How did producing Alhaji Bai Konte's album come about?

Mark Pevar: We did a lot of planning, but it was also seat of the pants. My wife, Susan, received a grant to study the role of women in Gambian society. So, I had to figure out what I was going to do with my time there. [laughter]

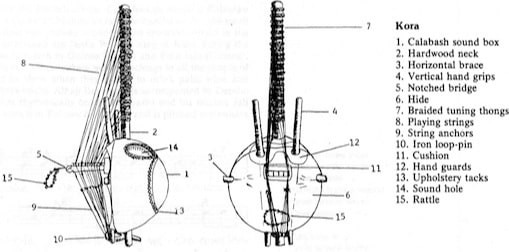

Susan Pevar: My father, Harold D. Gunn, was an anthropologist, and my parents had come home once from Africa with a kora – that was Marc and my first time ever seeing the instrument. My father also had made a little cassette of what the kora sounded like when tuned and played properly.

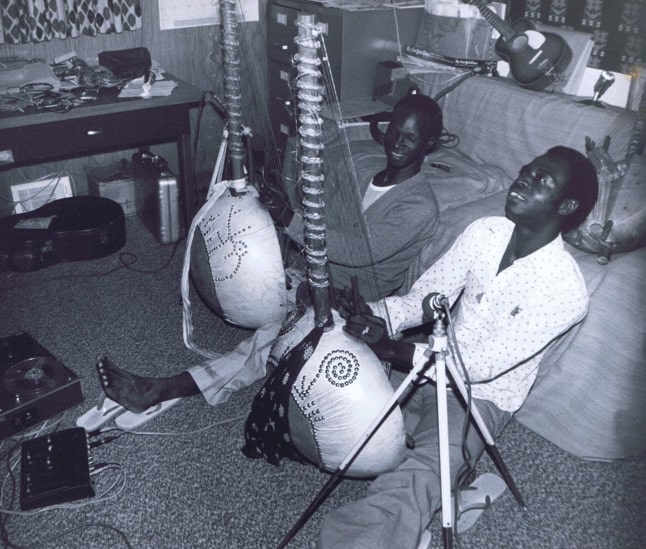

MP: Her father recommended that we get advice from his colleague, Dr. Anthony King, in the UK. And Professor King advised that we should live with a griot* family – observing how they raise children and how they spend their time, and then I could also spend my time learning the kora. He recommended the musician, Alhaji Bai Konte, in particular. Dr. King said that he'd recorded a very large number of griots, and he found that Bai Konte seemed to know more arrangements and more songs than all the other griots that he'd encountered. He said he'd be a good person to live with. But we went to Gambia with no idea if Bai Konte would even be there, or if he’d be interested in hosting us. We went through many people to meet him, but, in the end, we lived there with him and his family from November 1971 to November 1972 – a full calendar year, almost to the day.

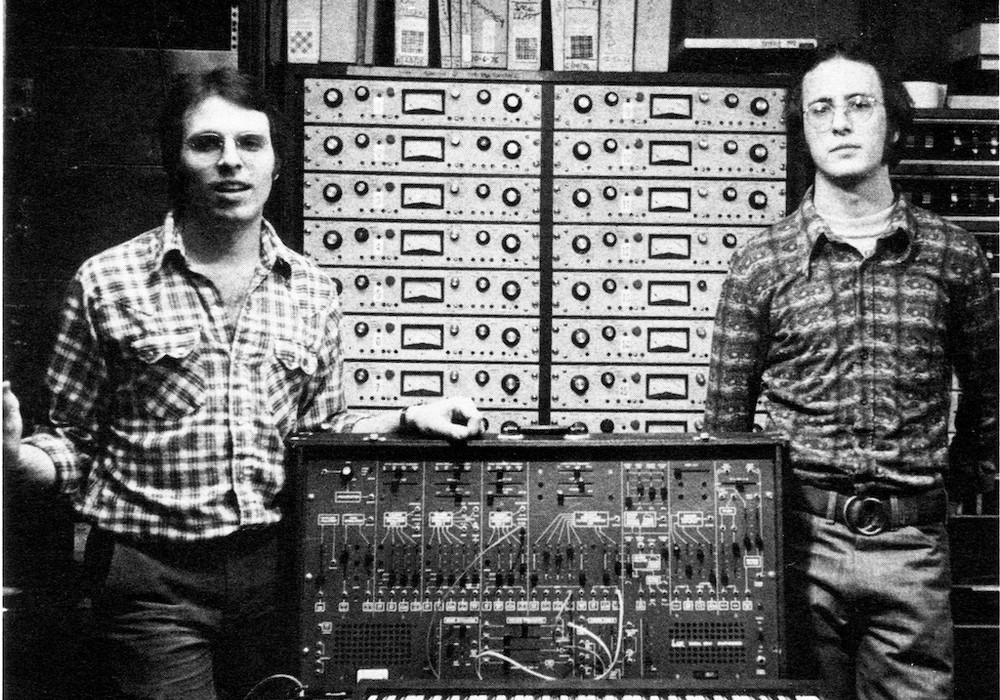

You bought the equipment from somebody who'd been to Africa and had recorded with the gear?

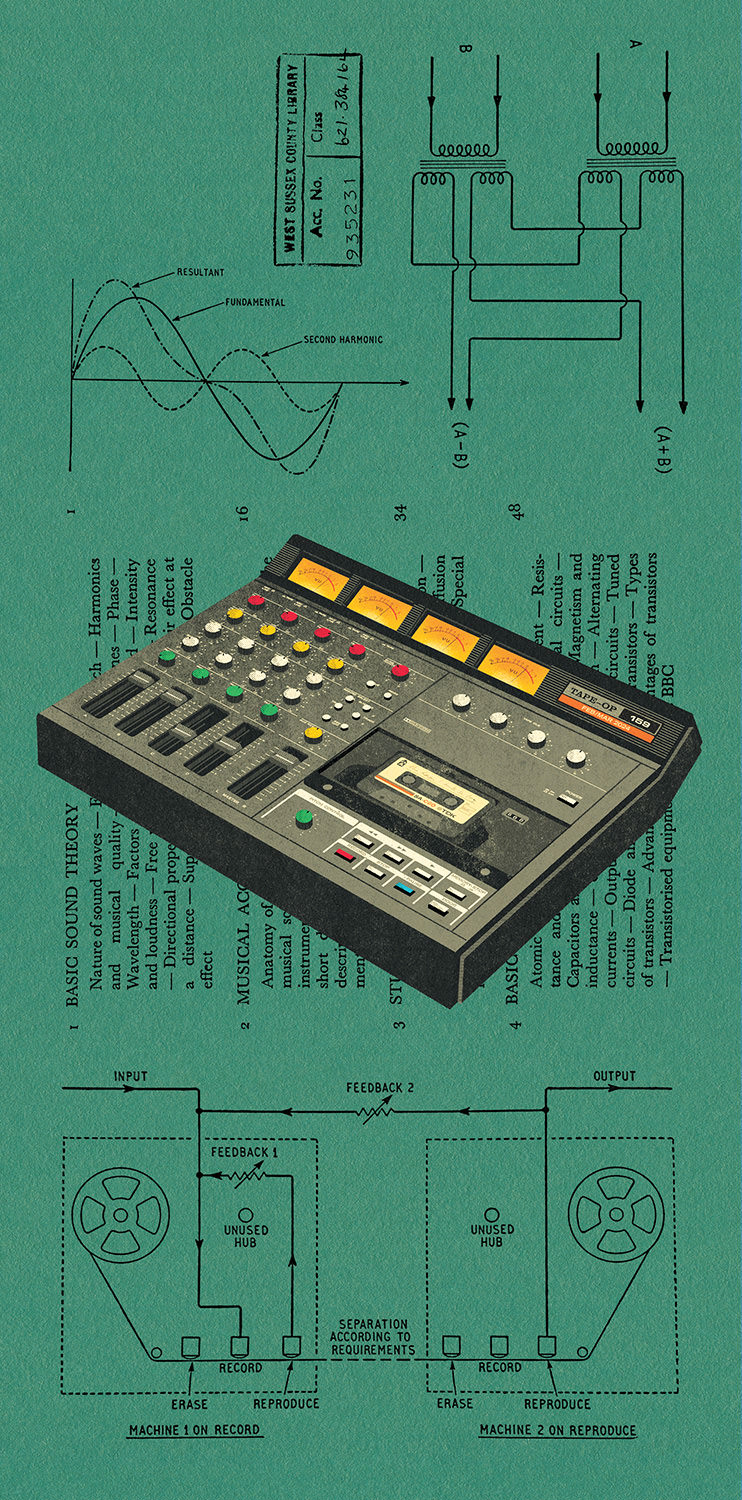

MP: We had a meeting with the Library of Congress, and they recommended that we meet with Curt Wittig. They said he had some excellent field equipment that he'd told them he was looking to sell so that he could get some new gear of a higher grade, like a Nagra [tape recorder]. We anticipated we would have no electricity in Gambia. When I purchased it all from Curt, it came with a 12-volt battery, which also helped power illumination at night since there was no electricity or running water there.

You had a background as an acoustic guitarist, but had you recorded before?

MP: I had taken guitar lessons for four years from a blues and country musician named [Gerald Lawrence] "Jerry" Ricks in Philadelphia, [Pennsylvania]. I had been a semi-professional folk guitarist. I specialized in Piedmont finger picking techniques and blues, which I later discovered had suggestively strong ties to Mandinka kora musical culture. I'd bought a reel-to-reel deck, and I lugged that to my lessons with him to record what he was teaching me so I could practice and not miss anything. I also had a little experience using a Dictaphone that my parents used in their construction office. I used that to record shortwave radio news and other broadcasts that I sometimes shared with friends. I did that because I had a Telecraft shortwave multiband radio that tuned in all over the world. I would record some of the news material to let people hear how vastly different the reporting was for the very same story on the same day, and things like that.

Would you then contrast that news material and edit different segments together once you'd recorded it?

MP: No, I did not know how to edit. I did not learn how to edit with tape until later when we returned from Africa. I met with Dr. Kenny Goldstein, a PhD head at the University of Pennsylvania's Department of Folklore. He listened to the album and he said, "Marc, if you're going to be making a record, you've got to learn how to cut tape. I'm going to show you." He did, and that's how I learned to edit. Later...