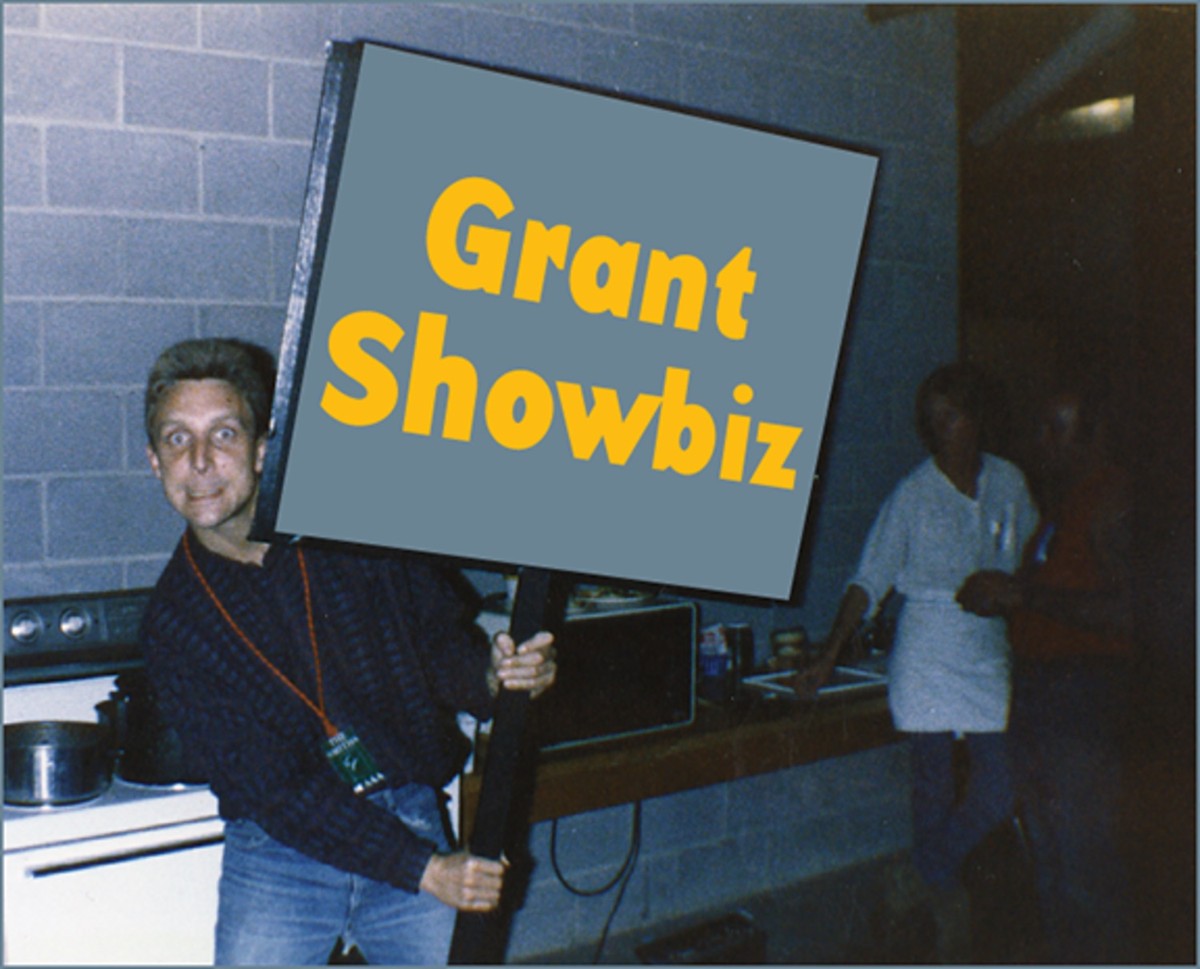

Grant Showbiz. His name pops up on records by The Fall, The Smiths, Billy Bragg, Alternative TV, Mood Swings and more. The name alone conjures up some flamboyant character, which he is! He got his start doing sound with a bunch of rootless hippies known as Here and Now, where he danced on the soundboard and pulled off crazy effects and mixes in a live setting. Then the hippies discovered punk, asking The Fall to come play shows with them, and eventually Grant produced The Fall.

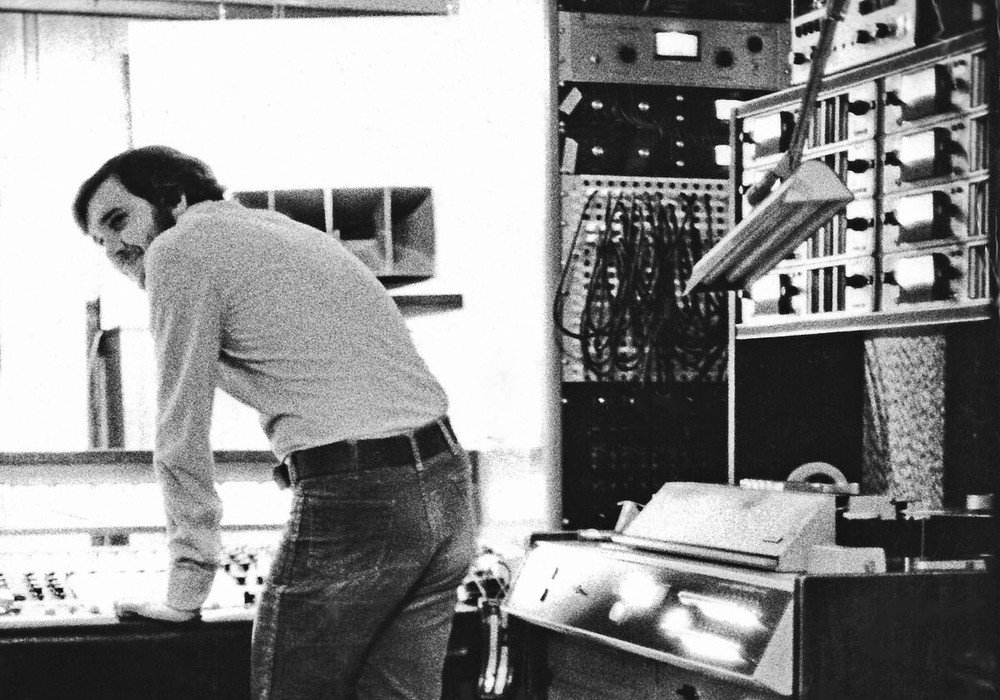

It was my first professional record. I did Dragnet in '79 and I suppose the last thing I did was this "Chilinist" thing, which I suspect is the basic track that they still used on the single, which must have been '97. The third album with The Fall was Slates. Adrian Sherwood came in and did some time with it. He had the whole kind of snare mic'd up on the stairs, put through the reverb and then fed back in. I thought, "Okay, I like this. I'm not going to spend as long as Adrian does getting it, but if it happens, go with it." You've heard a sound, it's worked really well, and you spend 3 hours setting up in your studio and it just doesn't work. I've really learned lots of things like pointing the mic down away from the [kick drum] beater, make sure it's right in there. And then one day you don't do that, you mic it from the front. The mic is outside the drum and it sounds great, and you're like, "Oh my God! Everything I've learned is wrong." But I can look back at The Fall stuff and think, "I don't mind." It's looked upon as brilliant stuff. I think The Fall are probably the best band in the world. 20 years of sheer brilliance.

Grant's career with The Fall lasted until leader Mark E. Smith's erratic behavior and alcohol problems made things difficult.

What you see is people going over their peak. Certainly with Mark E. Smith I was thinking, "Well you're not making sense anymore." It came to head for me when we made "Chilinest". I was up there working on it, and Craig Scanlon, who was one of the great guitarists of The Fall, had gotten a clarinet and we tried really hard to get it to work, to get a good sound. Then Mark heard it and said, "What the fuck is there a clarinet on this song for?" He told us to wipe it off the track. He went back to the pub and came back three hours later. We played the mix again and Mark was like, "This is shit. Where is the clarinet? That was the best thing on the track." I've seen Mark since then and he's much more stable now and I support him dearly — the last record he made was absolutely fantastic — but I just thought it's not for me. You make a decision. You say, "I can't do this anymore!" I'm very close to Mark, I'm in contact with him 8 or 9 times a year. The last time I saw him he was very, very sober after a lot of this trouble with the band and Steve Hanley finally leaving. So he cleaned up his act. He did say, "We should work together," and then I thought, "You've got to actually ask me to do this." I can't phone him up. He never did and I thought, "Okay, well, I'll leave this. I'll just carry on buying their records." As a kid, you think you're going to say to a cabbie, "I worked for The Fall. I've done about half a dozen albums. They're a seminal punk band." And the guy's like, "The Fall?"

After some of his early productions for The Fall and Alternative TV he opened his own studio. Briefly.

I formed a studio in '79 called Street Level. It was myself and a guy called Kif Kif. He was the drummer of Here and Now. We had lived on a bus together for five years. We went off and did this studio — and did a lot of great work — but he really didn't do a lot after that. He's kind of out of the loop, and if he had a little bit more sense at the time he would still be making music. I hate when people do that. He was a great producer, great musician, but the tide's gone out and he's been left there. The problem I had running the studio (until '82, when it closed) was that we definitely had to have heavy metal bands in. Now I look...