The phrase "recording artist" is usually reserved for the sensitive souls who sing and play the stuff that makes its way onto those shiny little discs. But there are some on the recording end of the process that truly deserve the title. Recordists who forge a distinct creative identity of their own that manages to distinguish and enhance each project they work on without overwhelming it. Tchad Blake is among them.

In the last decade, Blake, with frequent partner Mitchell Froom, has created an aural terrain unto itself. Like a latter Beatles album or Brian Eno [#84] recording, Tchad Blake's work is usually a "down the rabbit hole" experience — the listener is transported to another realm where the sonic texture asserts itself as a part of the creative process itself.

For a record world titan who has worked with a staggering number of heavyweight music makers from The Master Musicians of Jajouka to Tom Waits to Sheryl Crow, Tchad comes across as an unexpectedly down-to-earth guy (I easily spot him in the dining room of his luxury hotel: he is the only one in a red flannel shirt and jeans). On a November morning in Seattle, knee-deep in the current Pearl Jam record, his hunger and enthusiasm for the work of recording is infectious. Between spoonfuls of oatmeal, we discuss, among many other things, Jaipur in the wee hours (and why you might want to pack earplugs for a visit), his predilection for high-contrast sound, and why he loves being a Latin Playboy.

But like all those who climb to creative heights, he begin his trek at street level...

So let's backtrack a little. You started with Wally Heider in LA, right?

Yeah, at what later became Filmways/Heider Recording Studios.

And that was your first gig?

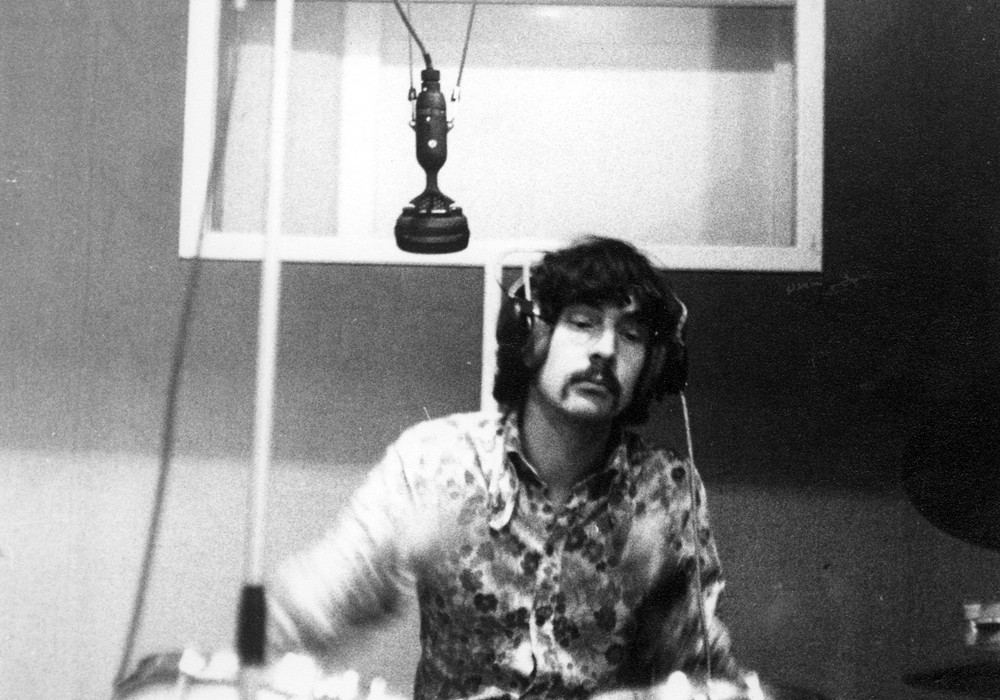

Yeah, I was a guitar player for years. Not a very good one, really. But it took me years to realize I wasn't going to get much better. And I got a job at Wally Heider's, just by beating on the door, to try to stay in music. I'd just done a TV show about sharks, where I was the still photographer and boom man. It was a great experience, going out with the sharks. I got it through this young guy who was the son of the director. He was a sound guy with Nagra. I'd always carried tape recorders around with me since high school, just to record sounds. Walking through hallways, doors closing. And I just loved it. I'd go home and listen to it at night. Sad, but true. [laughs]

Were you thinking about musical applications, or were you just into sounds?

It wasn't really about music, but just noise. I put weird guitar noises to it, synth noises. And I used to love feedback. It was more avant-garde, almost like installation stuff, which I tired of pretty quickly. It got pretty stupid after a while. [laughs] But it was fun at the time. I just loved the sound. It wasn't the music so much. I was never a composer. I just liked sounds. So I met this guy...

The shark guy?

Yeah, great guy; Nick Webster. He used to build robots and go to the Himalayas with his dad to look for the Yeti. And he said, "You know you could get a job. You could be a recording engineer. If you like all these sounds you could just go do it." And I thought, hmmm, really?

How old were you at the time?

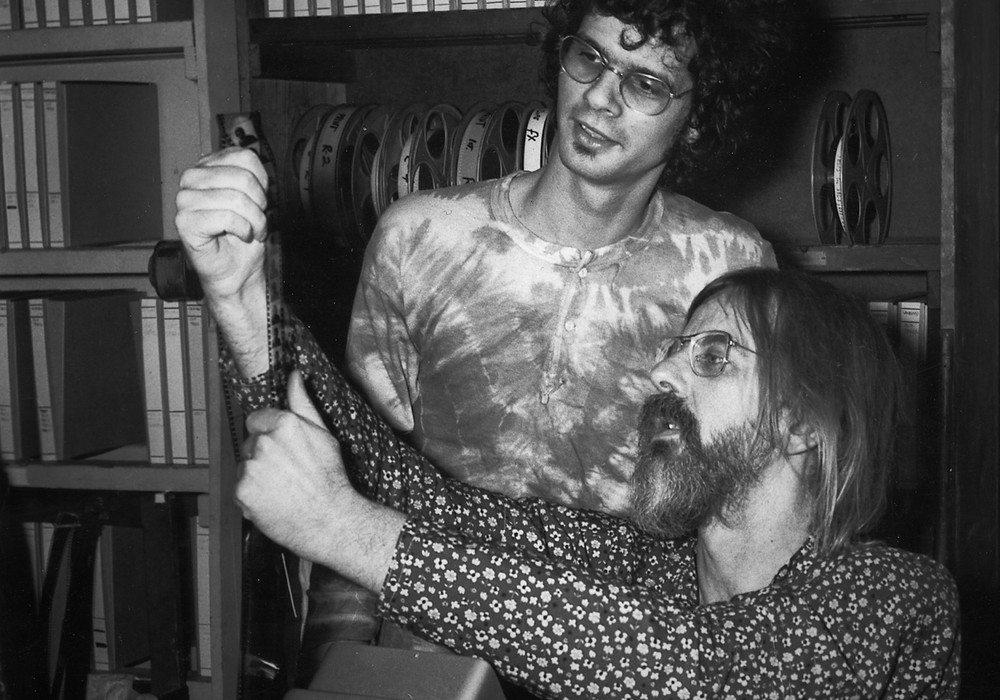

About 19. I actually played a session as a guitarist at Wally Heider's and I met an engineer there who told me what I should do and it interested me. So I just went pounding on the door everyday for 2 or 3 months. One day they said, "We need someone to work the equipment room." And then 2 days later they said they needed someone on the phone at night down at the other studio, which was the RCA building in Hollywood. So they took me down there and showed me this set-up. It was a live set-up in this huge room, Studio B, which was a famous old room that Wally Heider had taken over. And it was the Rolling Stones and they were recording what would eventually become Tattoo You.

And what were you doing?

I was just on phones and running for ribs at 2 o'clock in the morning. I was a runner and a janitor. Cleaning up after everyone, you know. It was a great studio to work in. It totally was not about anything technical. It was just about keeping a session going, you know. In fact they didn't want you to learn too much technically. I was caught reading a manual on re-aligning a tape machine and it was taken away from me.

So you were being mentored, but they didn't think technical training was what you needed?

No. They had tech guys for that. As assistant engineer you could record. But not really. Learning how the tape machine worked wasn't where it was at. But they had some really good engineers there. Really old school. But I used to just go and hang out. Everyone was really friendly and the sessions weren't closed. I mean, you couldn't just walk in off the street. But engineers would always say, "Come by if you want to hang out." Because they knew they could get you to do stuff. "Go move that microphone, go get that other microphone, go get us some food." It was really great.

So what sort of things were you picking up at that time that you could use later? When did you get your hands on the board?

The board I got my hands on right away. They used to let me go in...