What synthesizers did you start out with?

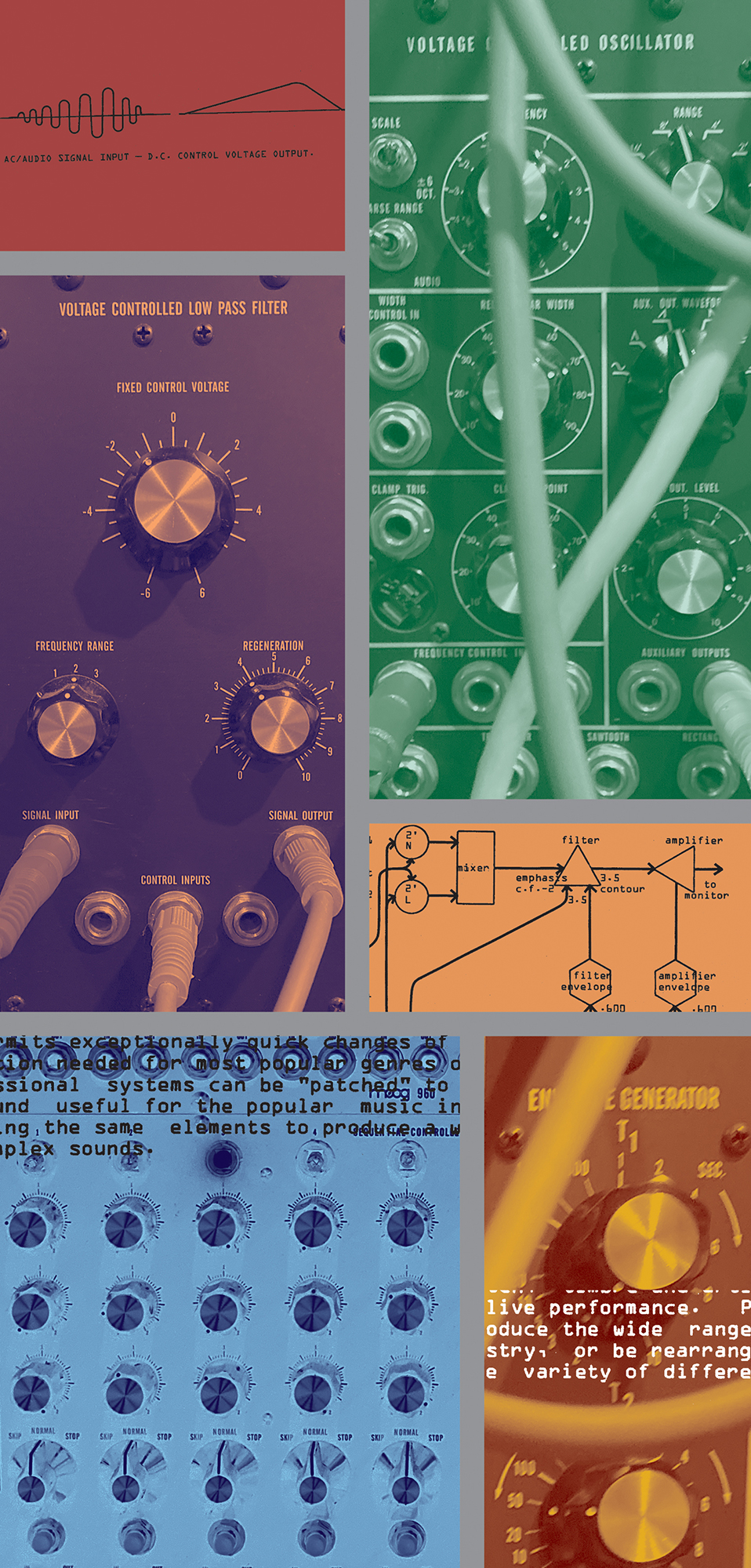

I started in ’78, and my first synth was a Roland SH-3A. I soon bought an [ARP Instruments] 2600, which I guess they call it semi-modular, but you patched it too. It had the basic signal flow set, but I could override it with patches. In early photos, you'll see that my classic setup in the '80s was the ARP 2600 with three ARP Sequencers mounted together above it. I had some other little modules that came from guys that were making them at the time. And then it was the [Moog] Micromoog, ARP String Ensemble, and later I brought in the Oberheim polyphonic synths. I was living in Culver City, [California,] and Oberheim was in Santa Monica at the time. I knew a lot of guys designing there, so I was playing prototypes of the Oberheim Xpander with no graphics on it! There was Sequential [Circuits] and E-mu Systems up north [in San Francisco and Santa Cruz], and Korg and the Japanese synths were coming in, but Santa Monica was ground zero at that time for me and synth development. Marcus Ryle was designing a lot with Oberheim, and then went on to found Line 6. There was also 360 Systems and JL Cooper Electronics. It was really a feeling of being at the core of that.

Polyphonic synthesizers were not available when you first started playing, right?

They were not. The ARP String Ensemble was the [Eminent BV] Solina String Ensemble from Holland. You could play chords on it, but it was more in the vein of organ technology. I was drawn to that at the very beginning, because I heard a lot of the European and German school, like Klaus Schulze and Tangerine Dream, playing these beautiful chords on Farfisa [organs] and some early string synthesizers. That's where we were getting the polyphonic component to the music at that early time. With the ARP 2600 and its three oscillators, I would tune it to a chord and then I would play the chord with one finger.

[laughs] Right.

Those early days of the one finger chord live on here now; so many of the new synths now have chord memory and you can load up as many notes as you can cluster up on a chord, using both hands; then you hit "hold" and have a ten-note chord that you can then do amazing work with. That all started in the early days, through the limitations of polyphonic and having a three-voice monophonic synth that I would then play through tunings like that.

I remember seeing synthesists use little lead weights to put on keys to hold down notes.

Well, that's the early hold button there. My frequent collaborator, Robert Rich, would use fishing weights, and we'd all have our own little special icons that had enough weight to hold the plastic keys down.

I've used masking tape, but then it lets go accidentally!

I also was in the tape school as well. Or matchbooks that you could stick between the black and white keys. If you look at Klaus Schultz's Moondawn album, as we did as young aspirants of the music, we would study it with a magnifying glass and see on the back cover that there were certainly weights on some of the keys. That was the universal "hold button" that we would all do on the early analog keyboards.

Something physical and simple.

Yeah. With modern synths I see hold buttons, but occasionally I think, "Where's the hold button?" You can get a modular world going now with the sophistication of the polyphonic synths, like the [ASM] Hydrasynth, where they've got modular aspects built into them now. It's quite powerful and amazing. I have a few of the Hydrasynths, and I’m quite fond of the little Hydrasynth Explorer; it's like a baby Xpander. Glen Darcey, who designed it, worked a lot with the Xpander and wove in those components where you can have matrix patching and go way beyond. It's a...