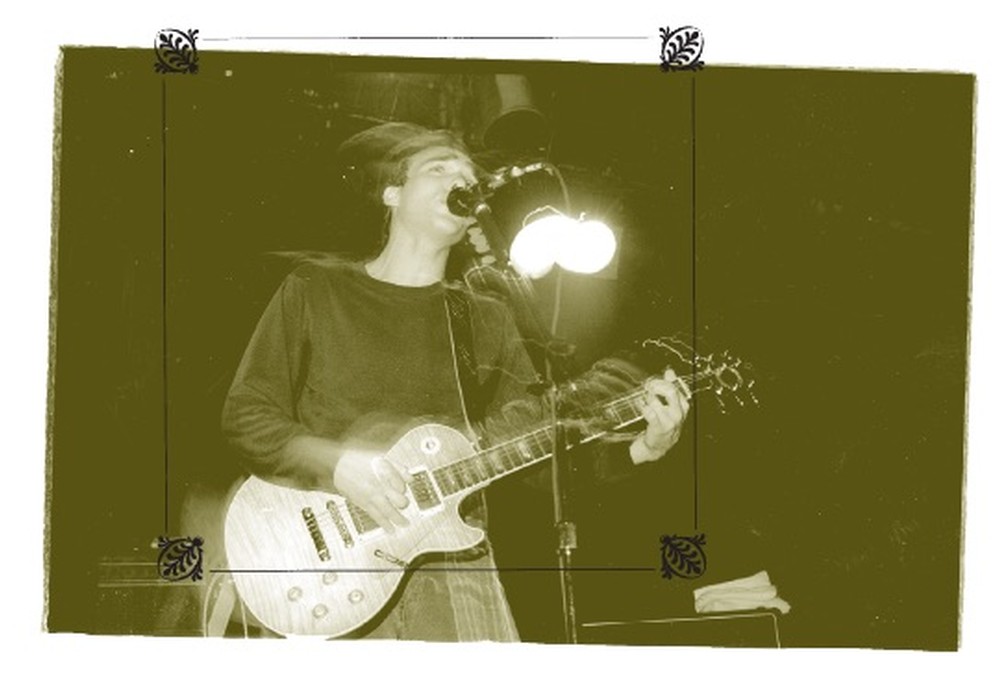

While I only casually follow British music magazines like The Quietus and Uncut, their frequent championing of the band Lankum caught my eye, and upon hearing the 2023 album, False Lankum, they finally grabbed my ear. In the same way that Fairport Convention updated British folk through The Beatles and The Byrds, and The Pogues merged Irish music with punk rock, Lankum has mixed an overtly-traditional approach to Irish folk with modern influences that I couldn’t quite place. It was impossible to tell how some sounds were created or processed and seeing live video of the band only added to my surprise. Speaking to recording and mix engineer John “Spud” Murphy helped me better understand both how he achieves their unique sound technically, and also a bit about how he and Lankum came to develop this approach. (Murphy’s band ØXN further emphasizes these electronic aspects on their excellent recent album, Cyrm.) I also enjoyed his great stories of his work with underground Irish bands, One True Pairing, Anna B Savage, black midi, and lots more.

I first learned about your work via Lankum. You got connected with them doing sound for a television show?

Yeah, it was called The Parlour. It was shot upstairs in [Dublin music venue] Whelan's, in a room that's called Parlour Bar, with mainly Irish music. That first event with Lankum [then known as Lynched] was a three-part show; it was a live band, then an interview with [presenter] Danny Carroll, who conducted it with two industry people, and then they included previously-shot footage from the main venue in Whelan's with Lankum and Sleaford Mods. The broadcast itself was a pre-recorded show with some post-production.

Were they interested in not sounding like a traditional folk group?

Yeah, exactly. I manipulated the low end of that track, and the band initially got a little bit apprehensive, saying, "What did you do? It's too much." I invited them out to my mix room; we played around with the track for a while, and then everyone was in agreement that it sounded great. I wasn't after destroying the track. We seemed to have a bit of a rapport and were chatting. They were telling me about how difficult they were experiencing being on the road, because of different engineers and traveling around Europe with instruments that are Irish. A lot of the engineers they came up against would have never seen or heard any of these instruments. They did not know if any processing needed to be done to them or what way to mic them. Because they were playing so many instruments, and had so many live microphones on the stage, they were experiencing a huge amount of feedback issues. I had a bit of live engineer engineering experience with bands from a decade previous and I said I'd go and see if I could help them out. Initially it was supposed to be short term – I was going to set up things for them and make it a bit streamlined. But it kept developing and growing over the months and subsequent years that I worked with them. I started to add a few contact mics to some of the lower frequency instruments, and I was ultimately able to run them into lower octave manipulators. They signed with Rough Trade and recorded their album [Between the Earth and Sky] in a different studio. They were having a bit of a difficult time getting a sound that they liked out of those mixes, so they got the stems and brought them to me. The process for the rest of that record was a combination of me re-amping and re-recording different elements. For instance, for the uilleann pipe drone on the start of the first track on that album, “What Will We Do When We Have No Money?”, I rented out a church in Dublin City Centre for the day, went in with some speakers, and re-amped it out extremely loudly into the church and recorded it. I then sent out a lower octave into the same church and captured that. Then I sent another distorted version into the church and captured that, and then combined it all again in the computer. There was a lot of that manipulation of the source sound going on. Coming towards the end of the album being mixed, Ian [Lynch] from Lankum was writing a new song and the band thought the album was missing another original number. We decided to track that, and that was “The Granite Gaze.” That was recorded in my project studio, which is called Guerilla Studios – a very rough and ready space under a train line in an arched red brick tunnel.

What type of mix set up did you have at that point? Did you have a console?

I had an AMEK TAC Scorpion desk that I was tracking in on, and I had Universal Audio converters. When they asked me to mix the album, I bought a Neve 8816 summing mixer, so I was running everything out of the...