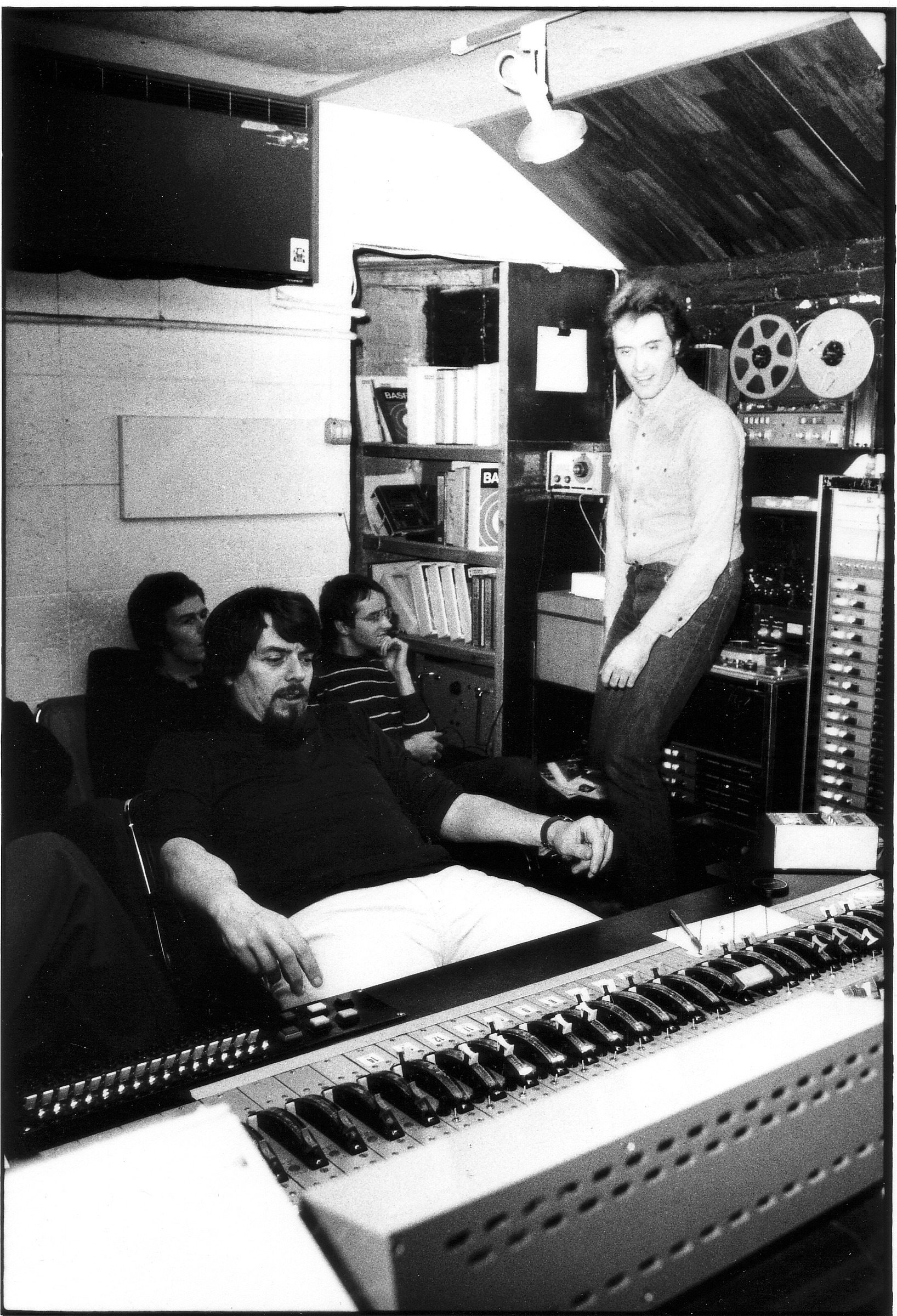

If I look at my record collection, there are so many favorites that John Wood engineered, mixed, and produced. This notably includes the first Pink Floyd singles, as well as albums by Nick Drake, Fairport Convention, Sandy Denny, Judy Collins, Squeeze, John Cale, Nico, and John Martyn. I've wanted to interview John for years, and when a fellow writer mentioned John'd be into it I jumped at the chance. John, along with his partner, Geoff Frost, started Sound Techniques studio in London in 1965. When producer Joe Boyd [Tape Op #60] showed up, John and Joe began a long working relationship making records with many of the above artists. Geoff built Sound Techniques consoles, shipping them all over the world for a while, and John eventually became a freelance engineer working in many cities as well. He currently resides in northern Scotland, and he still keeps busy with album and mixing projects.

Did you ever play any instruments?

I played the violin a bit for a couple of years, and then it was probably too much hard work. I was about nine and my father took me to see [Yehudi] Menuhin in Croydon, and that sort of finished it!

Yeah. Was it a feeling of, "I'm not going to get there"?

Pretty much, yeah. It was way before the ideas of the Suzuki method or anything like that. When I first learned the instrument, I was just playing pizzicato on open strings. They wouldn't let me touch a bow. It was very formal, and the idea of ever getting a tune out of anything at the end of the day was very remote.

I know you were considering being a metallurgist.

Yeah.

How old were you when you first applied to, and ended up, at Decca?

Nobody would be employed that way now. I would have been about 19 or 20. I was going to be a metallurgist and it just didn't work out at all. It was a stupid thing to do in the first place, but there you are! [laughter] I was brought up in the era when, to some extent, the ambitions of your parents were foisted upon you, careerwise. Metallurgy didn't work out, and I didn't really know what to do. I had an interest in a hi-fi, in record collecting, and I used to go to a lot of classical concerts. I thought, "Maybe I can get a job listening to music and twiddling knobs." I wrote to Decca [Studios], I wrote to Abbey Road [EMI Studios], and I wrote to Philips [Studios]. I didn't know anything about independent studios at all – not that there were probably many in those days. I went to Abbey Road and Decca for interviews. There were extraordinary differences between the two. At Abbey Road, I was probably there for an hour and a half. They took me everywhere and I saw all the studios. I remember walking into Studio One, and they were rearranging after a break. It's like the whole of the LSO [London Symphony Orchestra] was in there, and I thought, "This is it. This is what I want to do."

That room is quite large.

I think [Edward] "Chick" Fowler was the studio manager in those days. He asked me loads of questions, and then he said, "Well, we haven't got anything at the moment, but if something turns up we'll be in touch." Off I go, thinking, "Oh, well, I'll probably never hear another word." About three weeks later I got a letter from Decca, went to Broadhurst Gardens, and it's completely the opposite. I had this ten-minute whirlwind tour, and five minutes with Arthur Haddy, who was the studio manager of Decca. I can't even remember the questions, but he turned around and said, "Well, boy" – he used to call everybody boy – "would you like to work here?" I said, "Why, yes, Mr. Haddy." He said, "All right. Start the first Monday in January." That was how I started.

Were you mostly in the cutting room at that point?

It was the early days of stereo mastering. They had two Neumann stereo lathes, and I was on the second one. It was being run by Peter Attwood, and I was put with him. I'd been with him about a week, and then he said, "Oh, I'm off to my clarinet lesson this afternoon." And that was it. They left me to it in the room. Decca did a lot of licensing in those days. They licensed RCA, and there was a label called London American, which was a conglomeration of the likes of Liberty and Atlantic. I used to do the monthly releases for RCA and Atlantic and – I can't remember them all. If you got through that, you might do a Decca one if the guy upstairs doing the Decca releases was getting behind time. If I got through that, I'd maybe get sent off to do editing. These were the days when they used to do mono and stereo separately.

Would you have to match the edits on different reels?

...