I’ve long been a fan of the seminal punk records that Richard Hell & The Voidoids made in the late ‘70s. Ivan Julian was a founding member, and he’s done quite a bit since, partnering with NY HED Studios [Tape Op #25] in the past, producing The Fleshtones, and he currently owns and runs SuperGiraffeSound in Brooklyn, NY. Additionally, he also puts out amazing solo records, like 2023’s Swing Your Lanterns.

Were you paying a lot of attention to the recording part of making records when you first started?

I’ve always been fascinated with that from my days as a pre-teen. I’d hear records and hear sounds, like the drum sound on [the Rolling Stones’] “(I Can't Get No) Satisfaction.” I’d think, “How do they do this? Why is it affecting me like this?” I’ve always been fascinated. Was I paying attention in the studio back then? Yes. I was constantly being told, “No, you can’t do that.” I thought a lot of the engineers were more technicians than they were musical. I thought I wanted to eventually have a place where I could record the way I wanted. People can come in and I’ll allow them to do anything, within reason. If it’s an idea, let’s try it. I accumulated pieces over the years, and that’s how it all happened. It used to be in a house I rented. The drummer would be in the stairwell, the violins would be down in the basement, and I’d run XLRs all over the place. It was pretty wild. I had a situation where my landlord was gone nine months of the year, and he lived downstairs.

Who were you working with back then?

Oh god, just local people. I didn’t really start working with people who had record deals until I was at NY HED over on Ludlow Street. Then I started working with Hunx and His Punx, The Fleshtones, and people like that.

The Fleshtones were around during the same era as The Voidoids.

It’s funny, but we never crossed paths. It was like that with some people. There were so many bands. Some people we’d met and hung out with, and others we just didn’t. I didn’t meet Keith [Streng, of The Fleshtones] until much later on. He heard that I had a studio, and I played him some music I was working on. He said, “We’re doing our next record with you,” and that turned into three records.

They’ve got a real loose, garage-y aesthetic.

There’s something about them. There’s a record I did with [The Fleshtones] called Take a Good Look. I loved working with them because basically all I had to do was press record. They came in, they were so well-rehearsed, and everything was just there as it was. Simple rock ‘n’ roll, but it’s good simple rock ‘n’ roll. The feel was there, the dynamics were there, and it was amazing.

Have you found that a lot of other work has come to you because of your past history?

Yeah, there are bands from South America, Spain, and France that come to me based on the Voidoids’ legacy. Also, word of mouth. People leave here happy. That’s my goal. Make the record and make it sound good.

I love the sound of the Richard Hell & The Voidoids records. They were so immediate.

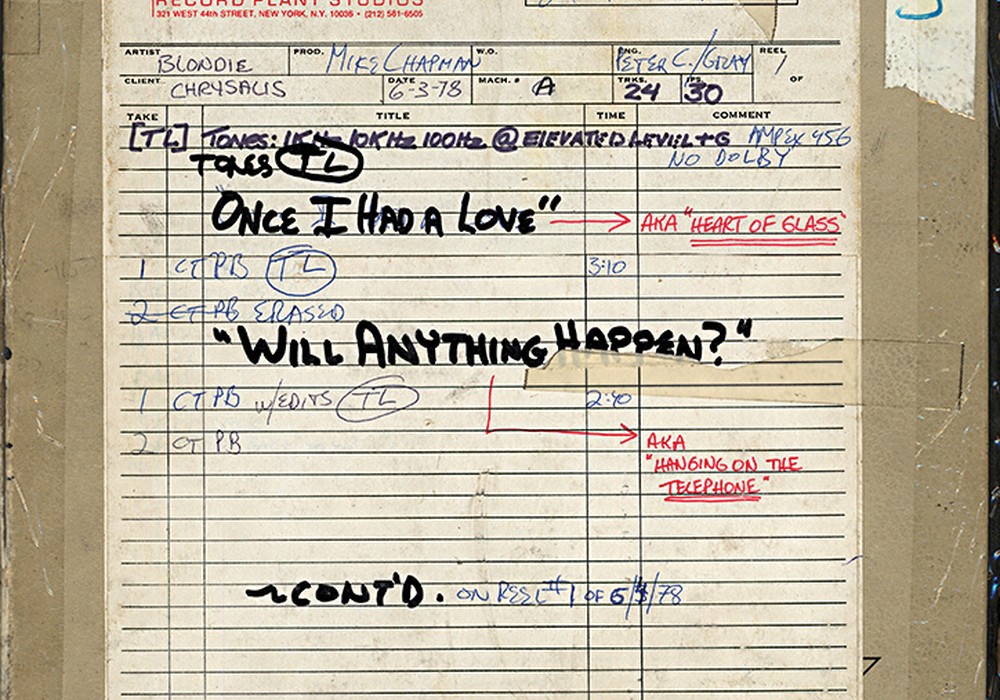

When we were making the EP [Another World], the predecessor to our debut album, I would ask for acetates every day and they’d give them to me. I have this pile of acetates from that session. This phenomenal stuff that you can only play once. We recorded that at Bell Sound [Studios], which was a place where The Shangri-Las and a bunch of people worked up in midtown [Manhattan, NY]. The board didn’t even have faders; it had giant RCA knobs.

What was it like in the studio making The Voidoids’ Blank Generation with Richard Gottehrer producing?

We had rehearsed for a long time. We might have done one or two gigs before that record came out. We spent most of our time rehearsing. We had our parts down and we knew what we were going to play. But we recorded that record twice. It was once done at Electric Lady [Studios] and once at Plaza Sound [Studios]. I always thought it was Gottehrer who wanted to re-record it, but Richard recently told me he wanted to re-record it, because he didn’t like how bombastic it sounded. It did, because we were using these giant Marshall amps with four and eight speakers, and the whole thing sounded like two bumblebees rolling...