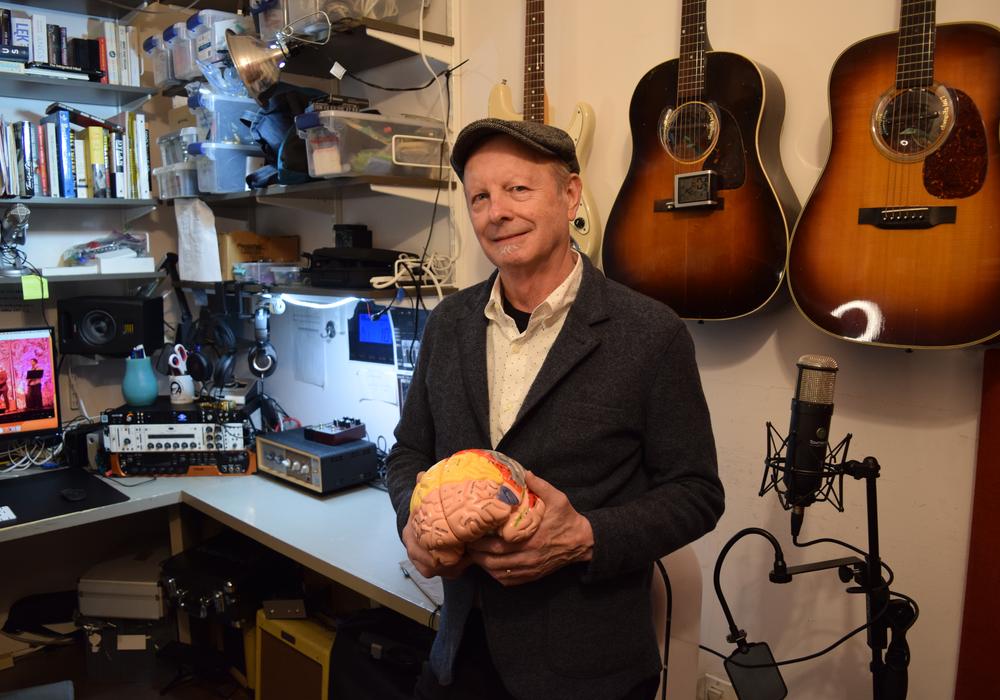

Jordan Brooke Hamlin is multi-instrumentalist, engineer, producer, and owner of MOXE Studios in Nashville, Tennessee. Jordan's portfolio boasts collaborations with Grammy-winning legends such as the Indigo Girls and Brandi Carlile. In this conversation with Lisa Machac (of Omni Sound Project), she opens up about her unconventional journey in the industry, her passion for creating a nurturing environment for artists, and the art of balancing technical prowess with raw emotion in the studio.

How did you make the transition from being a musician to being an engineer?

What's funny is, even now, I feel those in the same place in my experience. I wasn't necessarily thinking of them in such different lanes, because I was already a generalist, and sort of still am. I have to make peace with that. I feel like I'm always fighting an apology about being interested in many things, and not focusing and being great at something. It seems like that's bad, but that's my proclivity. So, the transition; it's not like I left one, and now do the other or vice versa. When I'm collaborating with somebody on a project, it's like, “What do you need me to do? How am I best utilized on this project with these people and their skills?”

When you're producing and playing music for a client, do you have another engineer there?

I've probably got five things in my production pipeline right now in various stages. Some I produced, engineered, and mixed. I'm planning one coming up where I need it to go well and quickly. I don't need to be at the board, because I have a finite amount of bandwidth. So, I can engineer and produce at the same time, but those are two different parts of my brain. If I'm thinking about a converter error, I can't think about the emotional experience of the vocalist. I need to bring somebody in who I can communicate with about what I want to hear.

Do you have a roster of people you pull from?

I have a roster. I've got a very intense database. I use Airtable to run my whole life, and other apps that talk to it. This is really demented…

You're speaking my love language.

Yeah, I love this. There's so much to keep track of, whether it's crediting, technical data, schedule, or budget. I'm often working on projects that don't have a project administrator, so I have to have some touchstone resource so that I don’t have to memorize all the details of all the projects. I've got all these different tables that talk to each other. I make filtered views. If somebody wants a female drummer, I'm like, “Oh, let me send you these names – I already have their emails and phone numbers.”

Have you always been an organized person?

I'm thorough. The level of thoroughness that is satisfying to me doesn't always match up with everybody else. It can look slow, because people are often willing to push past things to just get it done. Often, on record making particularly, they're like, “I just need the track.” They’re skipping past what, to me, is the most important part of it. It feels messy and unstable unless I have information that I can access and reference. I need to make sure we're eliminating blind spots. I think it's a stress response. Some of the people who I think are “capital O Organized” are organizing from a different spiritual place.

I'm organized, because if I'm not I'm off picking wildflowers in the forest. Have you read Chris Schlarb’s On Recording [Tape Op #129]? It's full of wisdom about the recording industry and how to treat your clients. He talks about the cheap, fast, and good axiom – choose two, you can't have all three.

Lately, I’ve been thinking about the ways that we're making music. I think about it on a generational level; like whoever's here now and how we're going to be thought of. I want to make the best thing that these people can make in here. So often the ceiling is set before the artist does their thing, because of how many days they have in the studio, and how prepared they are going in. I'm trying to play with a different format. I have camps where I'll cherry-pick my favorite artists and writers and think about their combinations, and then put them up at my studio for a week. We have this feral clubhouse just off Music Row. We’re on 20 acres out here. It's a different vibe. If I can get people who want to invest directly in...