In a Pitchfork review of SML's Small Medium Large album, Matthew Blackwell wrote, “There were no rules at Enfield Tennis Academy (ETA). The tiny Los Angeles cocktail bar… became a destination for the new jazz scene’s westward migration from Chicago to L.A.; a weekly improv session led by Tortoise and Isotope 217 guitarist Jeff Parker was the highlight of the schedule. But despite its momentum, ETA officially shut down at the end of 2023, closing another chapter in the history of West Coast jazz. It will take a long time to uncover the full extent of ETA’s influence on the L.A. scene.”

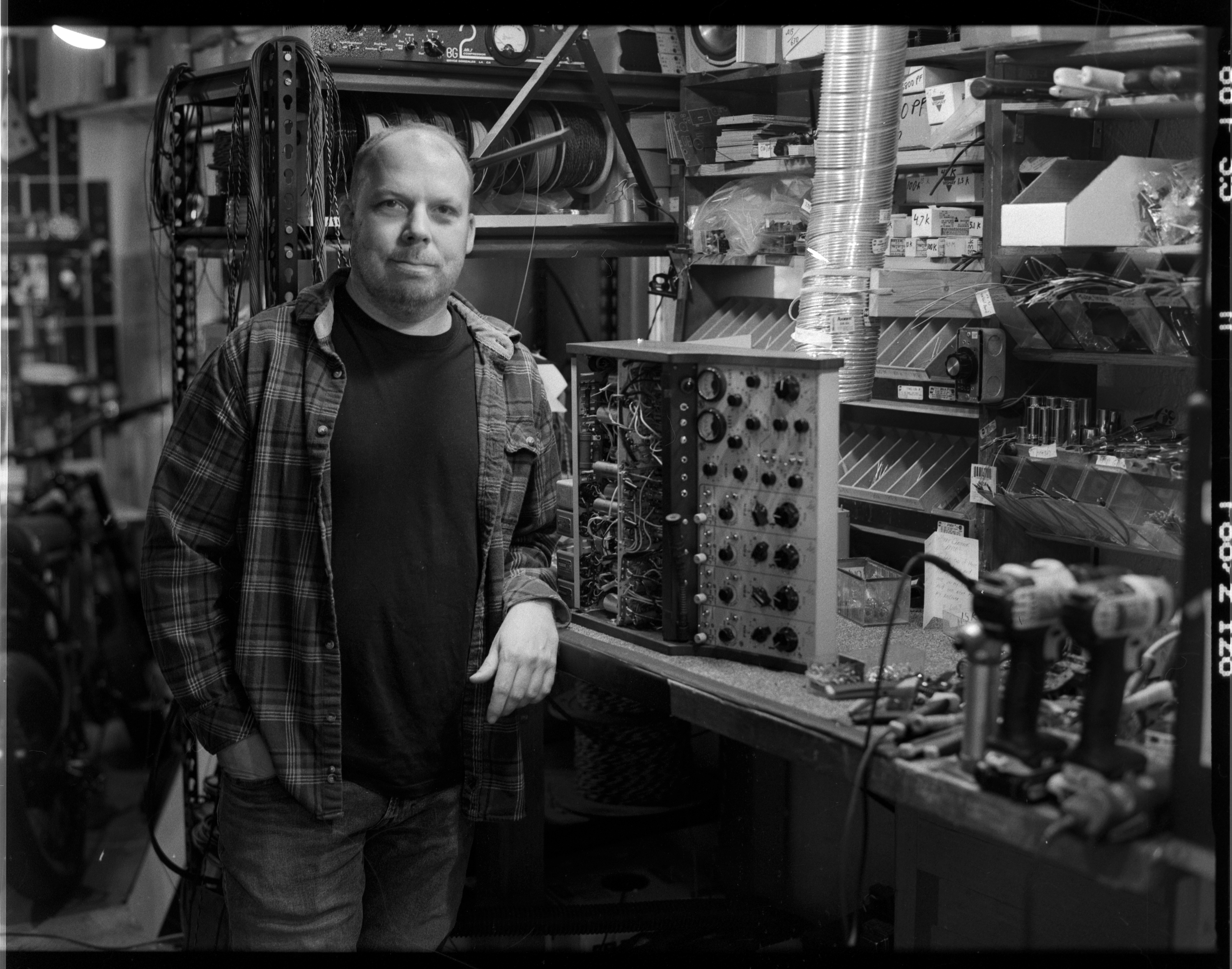

Since that review in July 2024, several other albums recorded at ETA have been released to similar music press acclaim, and the word has gotten out about the much missed venue. What's lesser known is that all of the recordings done at ETA were done by one person: Engineer and gear designer/builder, Bryce Gonzales. I've known Bryce for about 15 years now. We worked together for five years at my former studio, The Hangar, in Sacramento, CA. (Also now closed, after a 23 year run.) Bryce and I recently sat down for a chat about his role in the ETA recordings, and how the whole thing came to be.

All the ETA recordings were done live to 2-track tape, correct?

Yes.

How did the ETA sessions get started?

For me, it goes back to getting burned out on studio recording. When I moved to Los Angeles, I was engineering multitrack records for probably too long. I did that for almost ten years. I always built gear on the side, like I did at The Hangar. But as music recording got more intensive on the computer, I was never that good at Pro Tools. I'm good at using it in my limited way, but as the years went on people would demand more of the engineer, and I just wasn't good at that. I'd use it in a basic way, but when it came down to more intensive editing, software usage of [Antares] Auto-Tune and things like that, I didn't have an ear for it, and I became more and more frustrated. I was always an engineer, not a producer. I was lucky to work with a lot of great producers, and I enjoyed being just the engineer. But, at one point, I was doing it too much. I started working at United Recording. I got a room there, and that's when I quit engineering. The gear designing was what I found inspirational, at that point. I was never a producer and never wrote songs, but that move to United and focusing 100% on gear design felt cool. It was my version of writing a song and having a creative outlet. I was happy. But after a few years I started to miss recording. Plus, I wasn't as inspired to make new gear. I had made the [Highland Dynamics] BG1 [tube compressor, Tape Op #136] at that point, but hadn't really used it. People said it sounded good, but I didn't know. It sounded great in my office, but I was having trouble being inspired to make new gear. Nothing was coming to me. I noticed that [guitarist] Jeff Parker had moved to Los Angeles; I was always a big Tortoise fan. I would also see [drummer/percussionist] Jay Bellerose leave United early on Monday nights. I had heard he was playing with Jeff at this little place called ETA. I didn't know what to expect. Was it going to be like Tortoise? It was Jeff, Jay, Josh [Johnson, alto sax], and Anna [Butterss, bass], and they were doing standards. I thought it was great! I've always been into jazz, and I'm a big fan of Rudy Van Gelder [#43], Roy DuNann, and the records they made. Then it hit me, "I've got to record these folks here." We had Jay Bellerose, who's an insane drummer. Anna and Josh are ridiculous musicians. I would sit there listening, and I started getting annoyed that I wasn't recording it because it sounded so good. I'd never recorded any of those people. I almost worked with Jay in the studio a few times, but it never happened.