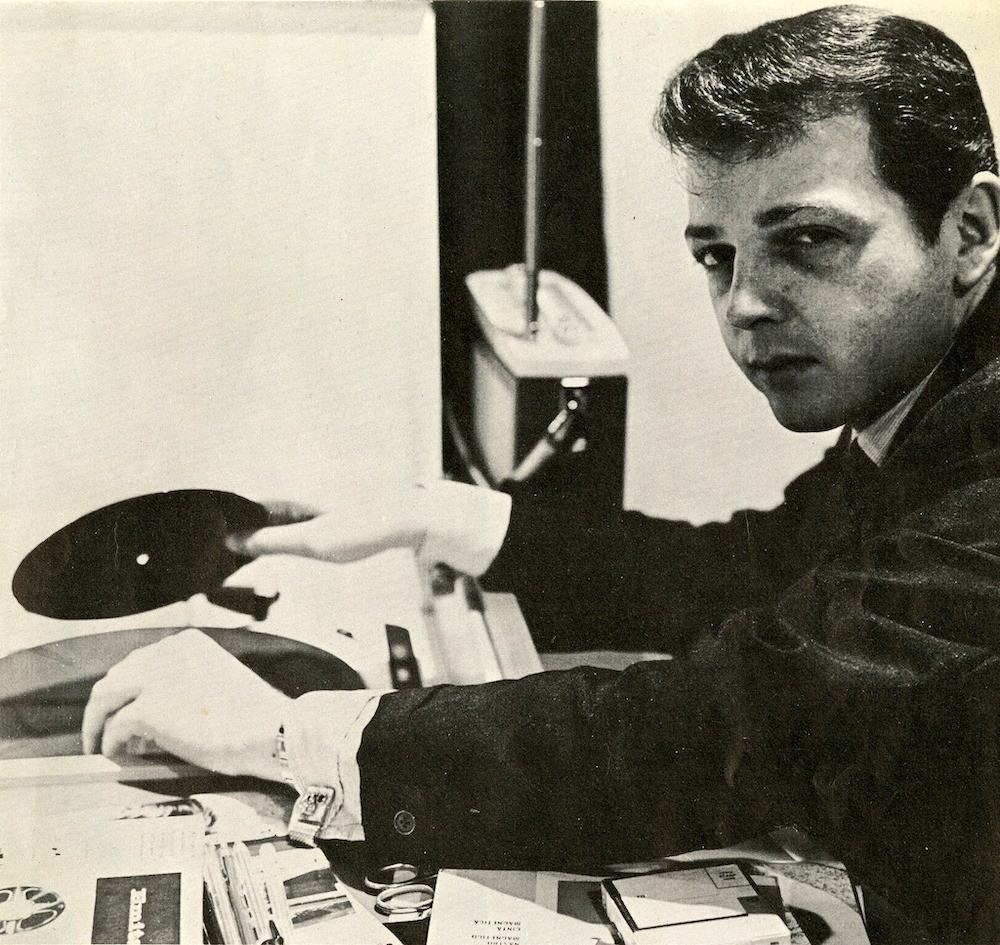

When we interviewed him at 86 years old, Shel Talmy had no intention of retiring. He had continued to look to produce new artists that excited him. In December 2024, Shel passed away, leaving behind a groundbreaking history of record making. As an American in Britain during the early ‘60s, Shel set a whole new bar for the explosive rock sound coming out of London. With his work with bands such as The Who and The Kinks, Talmy was free to experiment with recordings while still staying within the accepted margins of public taste. He also worked with other illustrious bands, such as Small Faces, Manfred Mann, and on David Bowie’s early tracks. So, the next time you hear songs like “I Can’t Explain” and “You Really Got Me,” listen to the production as revolutionary compared to the normal “too polite” standards of the time. You can thank Shel Talmy for that great accomplishment!

How did you get involved in the music industry?

After graduating high school, I went to work for ABC television in Los Angeles but I quit after a year and half because it was very political. Fortunately, the next day my friend introduced me to Phil Yeend, owner/engineer of Conway [Recording] Studios. Phil was a nice guy, and he asked me what I’d been up to. Then he said, “Would you like to learn how to become a recording engineer?” I said, “Absolutely! Let’s do it!” So, that’s how I got into it. It’s almost unbelievable, but I started the next day. Three days later, Phil turned me out to do my first session on my own. It was a jazz group that I recorded. They wanted an edit, which I did not expect, and I had never done before. Especially the way Phil did, because he did it by hand instead of an edit block, which I don’t even think existed at that point. So, I sweated about three or four pounds off but I got the edit done! [laughter] I stayed there for a year or so until Phil, who was English, told me how great London was. I had not been out of the country. I thought I’d go for four or five weeks and see Paris and all that, but that didn’t happen. It was 1962 when I got to London, and I bullshitted myself into a job at Decca Records. I had a hit and stayed for 17 years. But before leaving [for England] I had a producer friend at Capitol Records, Nick Venet, who knew I was going to London. He gave me some of his acetates, which happened to be The Beach Boys and Lou Rawls. When I got to London, I had an appointment with Dick Rowe, the head of A&R at Decca Records, and after listening to the acetates he said, “You start today.” However, they then were testing me. They gave me three harmonica players called The Bachelors, and I had to teach them how sing. The first thing we did was a song called "Charmaine," which was a big hit. I had a number of hits with them, and I expanded from there. I always said from the get-go, “I am an independent producer,” which almost didn’t really exist in London back then. When I left Decca, I opened a little office. In fact, the woman who was working for me told me that there was a band called The Who that wanted me to come down to listen to them. I did – they were playing at a church hall and, about eight bars in, I said, “Fine. I’ll sign you. You’re the best band I’ve heard since I’ve been here!” Same thing with The Kinks. I was walking around to publishers looking for songs, and one of the managers for The Kinks came in with an acetate and said, “Anybody here like to listen?” I said, “I will.” I loved what I heard. I got them a deal with Pye Records, and I stayed on for years having done over a hundred tracks with The Kinks.

What were your recording techniques at the time?

I started out as a recording engineer in Los Angeles. So, a lot of what I did in England was use techniques I'd worked out before I got there. When I got there, I realized that nobody was using them. I was being told at the time that my sound was very different. In England during 1962, engineers were only recording with three or four mics on the drums and one on the guitar amp; it was pretty simplistic. They were not able to capture the drive and raunchiness that rock was supposed to have, or what I thought rock was supposed to have. The English styles of recording were too polite, and I wasn’t going to be polite!

How did you record The Who?

When recording them, the first thing I did was use about a dozen mics on Moonie [Keith Moon]. At the time, this was a new...