Grammy award-winning songwriter and musician Aoife O'Donovan has released three critically-acclaimed solo albums, is co-founder of the bands I'm with Her and Crooked Still, and has spent a decade contributing to the radio variety shows Live From Here and A Prairie Home Companion. Her new album, Age of Apathy, was produced from a distance by Joe Henry [Tape Op #129] during the pandemic lockdown, but you'd never know it from the incredibly cohesive sound and "in the room" energy of the recordings. Geoff Stanfield caught up with Aoife to chat on the eve of the record's release. This interview is from her Tape Op Podcast, took place in April of 2022, and has been edited for clarity.

I love Age of Apathy. It’s soaring and cinematic and feels so cohesive in the sense of the playing and the vibe, but then I read the credits and realized it was made during COVID, and in isolation where everyone recorded themselves.

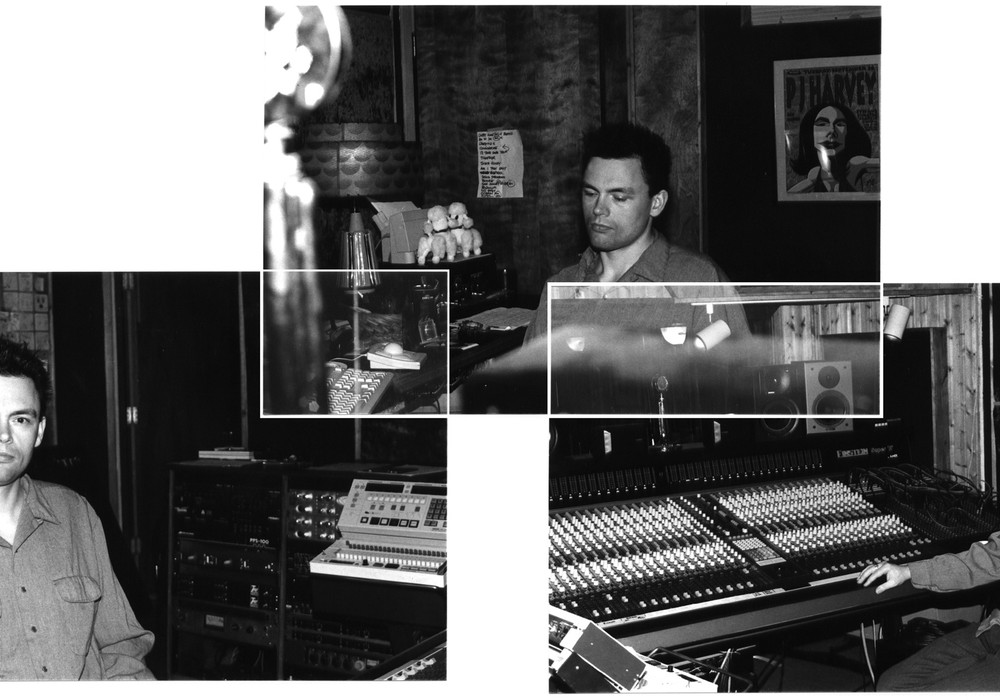

It was a pretty crazy process. I was living in New York and then we came down to Florida six months in [to the pandemic] and I had more space, more time, more sunlight. I was very creatively inspired and got everything flowing. Simultaneously, I was introduced to a friend and collaborator, [co-producer] Darren Schneider at Full Sail University [Advanced Recording Course Director], and we started diving into the recording process pretty early on in the writing process. It was the first time I've ever started demoing songs before I had a whole batch of songs written, and that that affected the outcome pretty dramatically.

What were the seeds of these songs? Did you do a rough start with a guitar and a vocal and build out from there?

Yeah, that's exactly how it was. I would go in and record what I thought at the time were just going to be demos. I wasn't sure if eventually, when I had the 13 or 14 songs done, how we would build them up. As I started working on these demos – and sending them to Joe Henry – it became clear that maybe they were a little bit more than demos. We were putting a lot of time into recording them. It was more time than I would probably put into just making a demo of a tune to see how it sounded. We were layering and getting good sounds. Darren is a total wizard in getting sounds, and we were putting electric guitars, acoustic guitars, sometimes keyboards, and sometimes piano and harmony vocals. We were making a track that we would be using as a demo, but what we ended up doing was stripping them back to the essentials of the demo. I would have recut the vocal to get a final vocal, and then we would send those tracks of guitar, vocal, and sometimes keys first to Jay Bellerose, on drums, and then he would send that back. He was recording at home with his partner Jennifer Condos. He would send them back to us and Darren would mix them in. I would show up at the studio, we would check out what Jay did, and once that got the green light and all those parts were organized, we would send it to the bass player, David Piltch, and do the same. He would send Joe an idea via voice memo, Joe would say, “Yes, go for it,” and then Piltch would send Darren his tracks. It was a very scatter shot situation, but it ended up sounding super cohesive. I think because a lot of the musicians, like Jay and Piltch, had played together a ton and for some reason it worked. It ended up feeling like these real musical contributions from these guys who I hadn't played this music with.

Darren did a great job on tying it all together. Joe Henry produced this record. I love his work! How did he produce from afar?

Joe is such a great guy; he has so much wisdom in his pinky finger. He's amazing. It's crazy to make a record with Joe producing and not be in the same room as him. What draws people to wanting to work with Joe is that you want to be in his presence. You want to be hanging with him. You want him in the control room saying, “Go," “That was a great take,” or “Let's try this again.” Because his energy is positive but it's musical and it's lyrical. It has so much depth. Doing this record remotely with him was a totally different experience, but he had just made his own solo record in this exact way, so he was no stranger to the concept of recording tracks and having people send him stuff back. He had also relocated from the West Coast to the East Coast, so we were both dealing with a newness in our own surroundings and connecting on that. We were speaking by the phone several times a week, sometimes several times a day during the recording process, emailing each other, texting, and he would Zoom into mixing sessions. As we were getting new tracks we would check in, put him up on this computer screen above the control room, and play him stuff. Like anything in the last two years, it starts to feel normal after a while. You're like, “All right, this is how we're doing it.” I remember one of the funniest things about making this record was that I didn't see Darren's mouth or nose for eight months. I'm not joking. I never saw him even take a drink of water. I remember when he got a vaccine before I did, he took his mask off and I was like, “Oh my god! That's what you look like, cool.”

Had you worked with Darren before?

We had worked together both as singers on a project that we did with the Cincinnati Pops [Orchestra]. That was a record called American Originals, and it was the songs of Stephen Foster with orchestra. That's where we met. It was in 2015. We became friends and hit it off.

It’s such a personal and intimate experience to make a record. You want to trust them and know their personality.

Of course. Yeah, I think the exact same. Even though we hadn't made a record together, we did have this connection, so we weren't starting from scratch. I think you're totally right. Had I called up a producer that I'd ever met before that would have been really, really hard.

Had you ever made a record like this before?

No, but even pre-pandemic we could send something to somebody to lay on a pedal steel part or a harmony vocal. I've never made a record without being in the same room as other musicians and had never put myself in that position to be like, “Alright I'm going to give you the base tracks.” I would always be like, ‘No, somebody else should do that." I definitely put a lot of pressure on myself to deliver a really solid base, but I think that it worked and that I was able to rise to the challenge. I'm proud of myself for that, because it was a lot of time and a lot of woodshedding that I did during the pandemic on my own music and guitar playing, and I was able to gain a solidity that would have been lacking had I attempted this at a different point.

How did you choose your collaborators?

For this record it was 100 percent Joe. I wasn't sure what to expect, because these were all people who I had never played with before and that was scary, but ultimately the absolute best thing that could have happened for this music. There's something about letting go. I hired Joe to produce the record. He thought it should be these people. I know I've listened to them on recordings, and they're great, obviously. I'm a fan of everybody who played on the record, but it was unexpected and that was one of the coolest things about it. I remember getting Allison Russell's tracks back for the three songs she sings on. I’ve loved her singing for years, but I've never sung with her, and I've never worked with her in any context. When we got her tracks back I had to calibrate myself to say, “Oh my gosh, this is incredible. This is not what I expected. This is not what I would have said to somebody to do but that makes it a million times better and feels way more collaborative.” When you can hire a musician and let them do what they are naturally going to do, it changes the finished product in a way that really connects with people. People have responded to all of the different elements on the record so far. Especially the singing of Allison Russell and Madison Cunningham. They're being themselves in the context of my record, and it's so cool.

Let's talk about some of the some of the songs on the record.

Yes please!

Sister Starling." I knew that I was in for something different when I heard all the woodwinds. It sucked me into what was to follow, and I love this tune.

I'm so glad that we opened the record with that because I do feel it's the beginning of the saga in this. It's about rescuing a wounded animal. That being a metaphor for almost where we are as a culture. The need to rescue; the need to save. But also, the fact that sometimes when we do, the person who we're trying to save does not want to be saved. They want to step away, fly away, and then you spend however much more of your time looking for them. Ultimately, at the end of the song, they apologize. They're saying, “I'm sorry," and it's what I was trying to say in that song. I don't usually go for just a two chord song. I feel most of the time I'm like, “Alright, how can I make this cool or work? How can I put in another chord?” But there was something about writing that song. I wrote it in drop C on the guitar, and it's capo’d pretty high and it has this real ringy vibe that was making me feel trancey when I was writing it. It set the scene in my mind of going through the motions, of finding something and picking it up and bringing it inside and putting it in a box. It's almost like the childlike wonder of thinking that you, as a six-year-old, can nurse a baby bird back to health and that somehow it won't fly away on you when it can.

It's nice to have an album that makes me sit down, stop, listen, and be looking forward to what is coming next. I think that's a real gift you give the listener.

I'm always so excited when I find a record that does that for me This fall I had a couple of records like that. Like the new record [History of a Feeling] from this great singer-songwriter, Madi Diaz. I had that experience where I put it on and I kept on being like, “God, I like every song.” Every song is great. Everything she's saying is getting me and making me want to listen to it again and again and again. Each time I listened to it I found something new. As a songwriter, and as somebody who has made a lot of records and will continue to make records, that is the goal; that you're creating something in its entirety that you want people to listen to. I think that we're living in an age of singles and, “What's the next track?” and, “How can we get this on the radio?” or, “How can we get this to be a viral video?” or whatever the fuck. But you can't go for that. You have to go for the truth of what it is that you're trying to say, and hope that will be the most rewarding for you and the person listening.

Well, it worked! How about “Phoenix”? This one feels like you're jumping off a cliff or running in a grass field.

Well, in some ways it’s that. It's being free of your material body in the sense that being free of your self-doubt and being free of the constraints of feeling like you don't have it anymore. You can't feel things anymore. You're not creative anymore. You don't have that newness anymore. A lot of the record has that underlying theme of trying to get back to the newness or the feeling. Like the feeling in your hands where you're tingling all over and you're excited about something. Or the feeling you get when you write a new song, or you create something, or you have a great show. I spent the first six months of the pandemic feeling so creatively dead. I think many people did. Just feeling utterly hopeless, and all of my creative energy was going to things like parenting, to a new recipe, or whatever bullshit was happening. It wasn't writing music or making music in a way that felt cathartic in any way. I remember writing “Phoenix," starting it, working on it, and feeling like finishing that song was me rising out of the ashes of everything that had come before it. It was the first time I've ever written a song like that and had that experience where like I don't think of myself as somebody who uses songwriting to process emotions, but this was that for me.

Let's talk about “Age of Apathy.” This one is interesting because it has this throaty electric guitar, like a Danelectro or something, and it has the ghost of Ricky Lee Jones somehow in it.

Awesome. I love that. This is such a compliment. In the chorus, “We came for New England's party, but the colors haven't started," the idea that there can be color without being able to see color, even when it's not there. That was one of the ones that we made a demo, and I thought we would do a different guitar part because it felt rudimentary, and it was a little bit out of tune. But then we tried to redo it, and it never had the vibe that that original one did, so we left it in because it has this real energy and sound. It immediately creates this mood when you hear it. One of the cool things about working at Full Sail is Darren has all these electric guitars there. Do you know the heavy metal band Trivium?

Oh yeah.

They're a huge heavy metal band from Orlando, and Matt Heafy, the lead singer, has his own model of [Epiphone] guitar that was there, and I played it on a couple songs. I played a metal guitar on this record, which is really funny to me!

That's hilarious and completely incongruous with the entire thing.

Yes!

When you get to “Elevators” on the record, it’s the first slight turn in the road to me.

This song is a turning point in that narrative for sure in that I'm out there. There's a lot of tension that comes from the rhythm of the song. I initially wrote the song in five, and then I straightened it out to six. If you know that, and then you hear it back, you'd be like, “Oh, that makes total sense.” A lot of the way I'm singing it, and a lot of the guitar parts are kind of still in five, but over six. It gives it this slightly unsettled feeling, which is also the feeling that the lyric has where you're sort of wondering what's what, and what's happening, and who is that? Is that me? Is that somebody else? Is that somebody who was me, and at a different time, or what's happening, and where am I? As a touring musician I end up in that situation a lot, where I yearn for this wild routine of my life on the road even though there's nothing routine about it. The only thing that's routine about it is the lack of routine. You look out the window, you're like, “Is that the Starbucks that I stopped at in 2006 that time when we were driving up Highway 1 in Crescent City, what?” I feel like I've had this experience even recently. We were driving from Chicago to Bloomington, Indiana, and I remembered for some reason we have always stopped at the same tiny gas station that doesn't even have a bathroom, and we forget every time? These weird “tour-isms” that anybody who's been on tour for their life will relate to. That's where I'm going with that. The yearning for your lost youth of drinking whiskey all night, being in a broken elevator, singing songs at the top of your lungs, and then waking up and being, "Where am I? What just happened?"

There are a lot of different narratives happening on these songs, but they're tied together with the sonics and the players and the record tells a story. We just talked about the era of singles and 30-second TikToks, which this is not…

No, this is not. I'm too old for TikTok. I'll jump on every bandwagon, but that's one that I just can't jump on. It's not for people over 35? What is the cutoff?

My daughter, who's 17, is already over TikTok.

Alright, good. I didn't want to make myself seem like too much of a curmudgeon! But yes, this is a “record.” I personally like records that are 40 minutes or less. I want people to be able to get to listen to the record and then turn it over and start listening to it again as opposed to never getting to the last two songs because it's too long. I felt strongly that 40 minutes was the cutoff. When we were sequencing it and putting it together that made sense. We were all in agreement about what the sequence should be, and ending with “Passengers” felt so vivid. I wanted to end on a hopeful, uplifting note,. The last line of the record is, “We’re passengers and the road is long,” and that's the takeaway that I want people to have. Like, "Okay, we're in the darkest hour. There will still be light." The darkest hour is just before the dawn. That's what I was thinking about when I finished that song.

Lucky Star” has a great abstract verse, and then such a payoff in the chorus.

It's so funny that you got that, because I was telling somebody about this the other day. I started writing “Lucky Star” in my head while jogging. It was early lockdown, during the pandemic. I was wearing two masks and jogging in Prospect Park [Brooklyn] and there was nobody. I was thinking, “I guess I'm going to keep my two masks on just in case.” Remember how we all used to do that? “In California, the summer’s always cold," and I had that sort of jump. Because I was singing in my head, I didn't realize how difficult it would be to sing live. It's a real shouty moment. It's super rangy, and I had to work a little bit to find the right key, but then that chorus is the payoff, because it takes it to a real pop country chorus. “If I had a little money, I would be somewhere.” That's the feeling of the song. It's like we're all in that same boat of trying to get out of the grind of being a freelancer a little bit.

I'm inspired by this record as a record maker as much as I am as a listener, because there's not that much happening. The arrangements are reasonably sparse and open, and yet it's so moving. That's a great lesson.

I have to applaud Joe for that, because I feel this – especially given the fact that it was all remote – could have gotten out of hand so quickly. I feel that even with tracks from all the musicians who played on it. Joe has this real gentle hold on the reins where it's so steady. We would get tracks back and I would say, “Oh, I wish we had more from Jay," “I wish that he had played like…” or, “I wish he'd given us an option where he played harder.” But as everything became clear, and all the parts were there, it was so apparent that Joe had the vision from the beginning, and that these parts were perfect. It was exactly as it was meant to be, without me knowing it, and I think that's one of the things that's really fun about making records. I am a band leader, I am bossy, and I want to tell people what to do and be the musical director of everything I'm involved in, but it's nice to sit back when I have so much trust in the people that I'm working with and let them do it, because that's what's why we'd hire them in the first place. So, I’m so thankful to Joe for that, and to Darren for making it possible every step of the way.

I think it's worth noting is that there are not a lot of cymbals on this record.

It's funny that you say that, because the drummer who I'm playing with live, my dear friend Robin MacMillan, when he got the record to learn it, he was like, “There are not a lot of cymbals on this record.” But there are some very important cymbals. There are a couple of very crucial cymbal moments!

It's a great lesson for drummers

I'm more of a tom's gal myself!

Before we go, are there any favorite songs that you want to talk about?

Well, a cool moment for me that that I'll leave you with is “Town of Mercy," the song that Joe and I wrote together that's on the record. That song was a turning point for me and how everything was made clear after we finished that song. He sent me the lyric, I sat down, and I wrote the music for that song with his words. His beautiful evocative, cinematic words. I played a simple piano part and a vocal. I did two takes, and we ended up using the first take. The very first song that we sent to Jay, was “Town of Mercy," and when he sent back his parts it was so minimal and so powerful. Talk about earthy. All these words that Joe had written were so descriptive, and I felt Jay's drumming put me right in that place. Then we sent it to David Piltch. One of my favorite moments on the record is that bass entrance on “Town of Mercy" and how I felt the first time I heard it because it was so new; all of this was so new. I'd been living with these demos and these seeds of songs, and you can get demo-it is, I guess. Everybody who's made records definitely knows about that! I hope people check out that track.