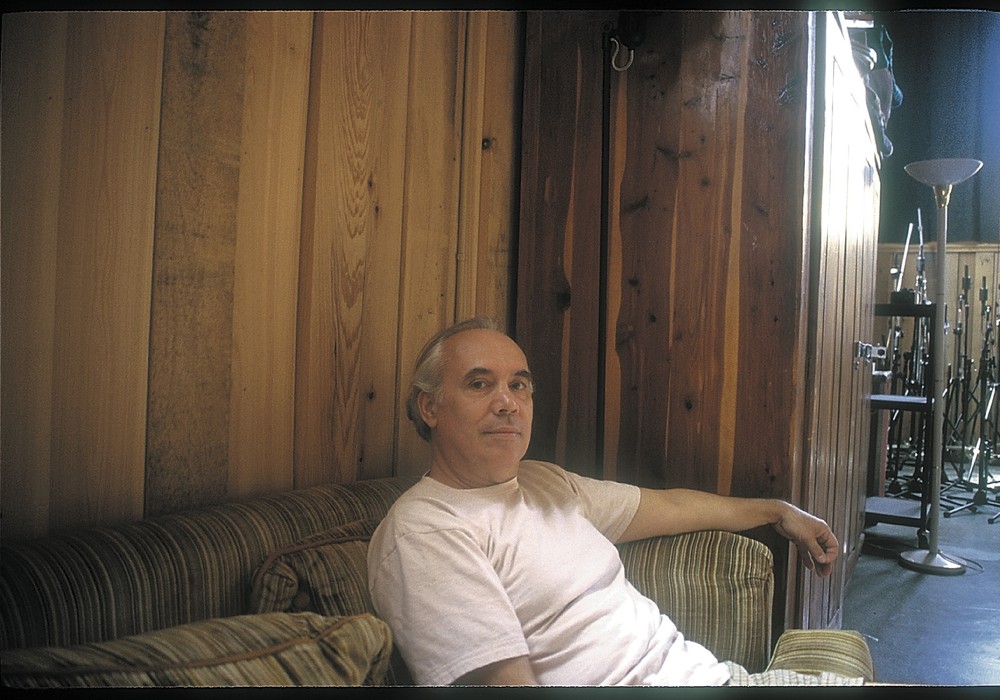

Azalia Snail’s recording career began with a TASCAM recorder running on batteries in the forests outside of New York City. From those early, carefree experiments, she has continued to embrace creation as a way of life, releasing solo recordings and collaborative works with her partner, Dan West. Decades later, her sound has evolved, but her mission remains: To channel joy and authenticity into music.

How did you get started producing music?

I always wanted to create music, but I was so insecure about it. I joined forces with this band called Fly Ashtray from the Bronx. We would go off into the forest, get high, and make all these recordings on a TASCAM. Eventually I got my own TASCAM. I had this little apartment in Greenwich Village, a fifth-floor walk-up. The weather was so bad in New York, so I would stay in and record. It was really intense – there were dozens and dozens of songs. Some of them made it onto records and some of them didn't.

Have you ever heard of Marge Piercy? She has a quote that says, “The real writer is one who really writes.” When I was looking at your work, I thought, “The real musician is the one who really produces music.”

In the '90s, when I did the bulk of my work, there were no distractions. I could make a living almost exclusively as an underground artist. I was living hand to mouth, but I was still able to concentrate on those creations while working the occasional temp job. Everything was obviously cheaper then, so I could live as an artist in the heart of New York City and not be struggling to make ends meet. When I moved to California, I still created, but I definitely had to work more.

You call your recent album, PowerLover, a protest album, but it is so joyful. One of my favorite bands is Le Tigre, who show that activist music can be fun.

There is a quote by Jimi Hendrix, “When the power of love overcomes the love of power, the world will know peace.” It's really simple, but it's so effective. I feel like more and more in this world people are basing their lives on, “How much money can I make? How much power can I have?” I love the idea of creating some joyful and happy instrumental music. I also love that people don't have to interpret the lyrics – just zoning out, putting it on, and getting into a mood. I'm very influenced by early Brian Eno [Tape Op #85] records, and I decided, "I'm going to make this all instrumental."

What's your process? Are you mostly tracking at home?

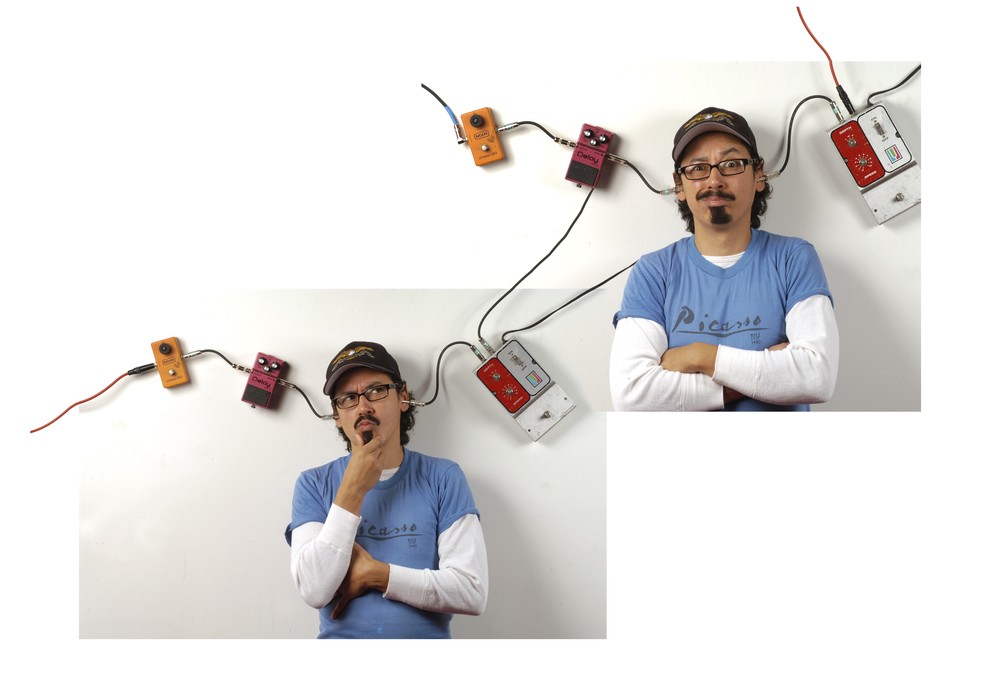

I’m using [Suzuki] Omnichords pretty much exclusively. I have about five different Omnichords, and that is my main instrument. It used to be guitar, but I feel I utilized a lot of my guitar ideas and there’re so many people out there doing it better than me. I fell in love with Omnichords in 1999, when I moved to Los Angeles and a relative of mine used to use one to accompany poetry readings. He dug it out of the closet and said, “Hey, do you have any use for this?” Back in the early 2000s you could get Omnichords on eBay for next to nothing, like $50 or $60. Now they're upwards of $700 or $800. It has become an important element of my sound. It's very expansive. It has a lot of lingering spacious sounds that I love. I do the ideas on voice memo. Then I go into a studio called Studio Red, that Adam Lasus [Tape Op #20] owns, and I put down my Omni tracks. Dan West, my husband, puts down the bass parts and then I do the flourishes back at home.

How did you and Dan meet?

We met at a party in Burbank. I was with somebody, and he was with somebody, so nothing happened then, but then we reunited about nine or ten years later. It's been great. I never thought I'd have a partner that I could be completely myself with.

What's it like collaborating with him?

He's really patient. We’re very much alike in so many ways, so it comes naturally. We were both established artists when we met, so I think we knew what we didn't want as much as we knew what we wanted. We respect each other and give each other a lot of space. We have two bedrooms in our little house, so we each go into our bedrooms and work. It's amazing. We got very lucky.

How do you know Linda Smith [Tape Op #163]?

I would always hear her name on the road. I toured a lot in the '90s, and people would say to me, “Hey, do you know Linda Smith? She reminds me of you. She's doing her own thing.” She wasn't touring, she was creating, so we never had the chance to meet. I was at a record release show in Highland Park and a friend of ours came up and said, “Hey, did you hear that Linda Smith's coming to town?” I wrote to her on Facebook, and we connected. She's such a gentle, kind soul and I'm so happy for her getting all this attention. Not a lot of women got the attention back when we were creating, but now people are unearthing these things and saying, “Oh, I didn't realize that these people were also creating at the same time,” because it seemed like it was always all men everywhere.

The Apples in Stereo [Tape Op #2] have referenced you as an inspiration.

Robert Schneider has been my main champion of my music. He introduced me to John Kiran Fernandes of Cloud Recordings, who was a big part of The Olivia Tremor Control [Tape Op #17]. When I was thinking about doing this album, I said to Robert, “Hey, could you think of a label that might be interested in this?” And he said, “Oh, you've got to do it on Cloud.” It took me by surprise, but then I remembered that I played in Ruston, Louisiana in ‘94 or ‘95 and they saw me play. I did this total psychedelic guitar thing with my crazy Super 8 films and all those guys were there.

What does nobody ask you that you wished they would ask?

The idea of discussing other influences is interesting to me. I'm just as much influenced by film, as well as everything from architecture to other musicians and artists. I'm doing a lot of painting now. Opening my mind to let all that enter into my headspace is really important. It influences so much. I'm always trying to reach out to other artists and see what I can do to help them. I think that's an important aspect of being an artist.