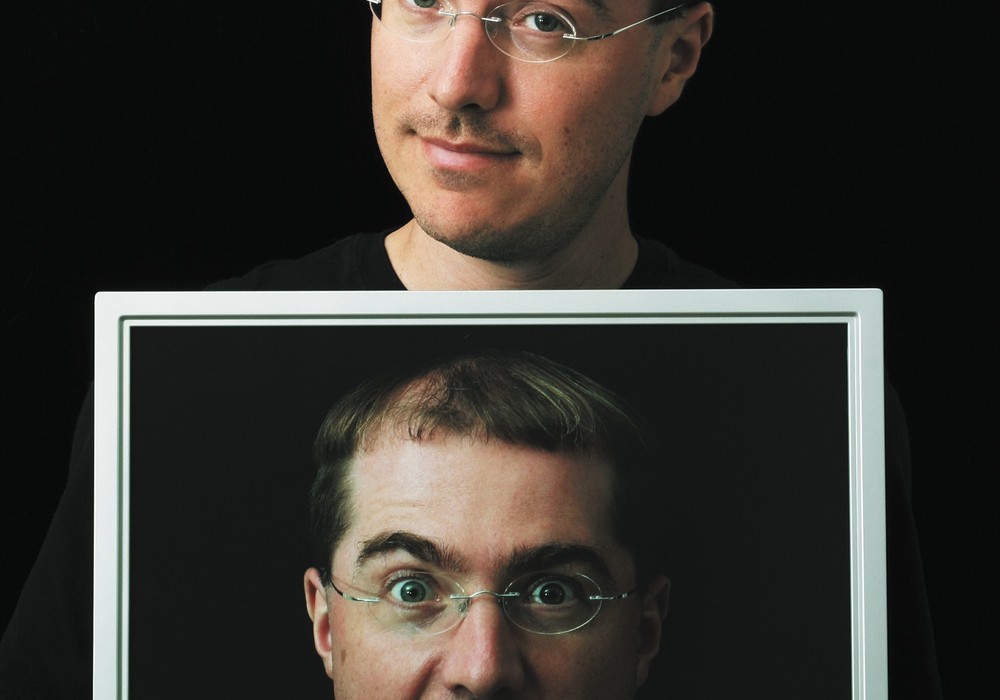

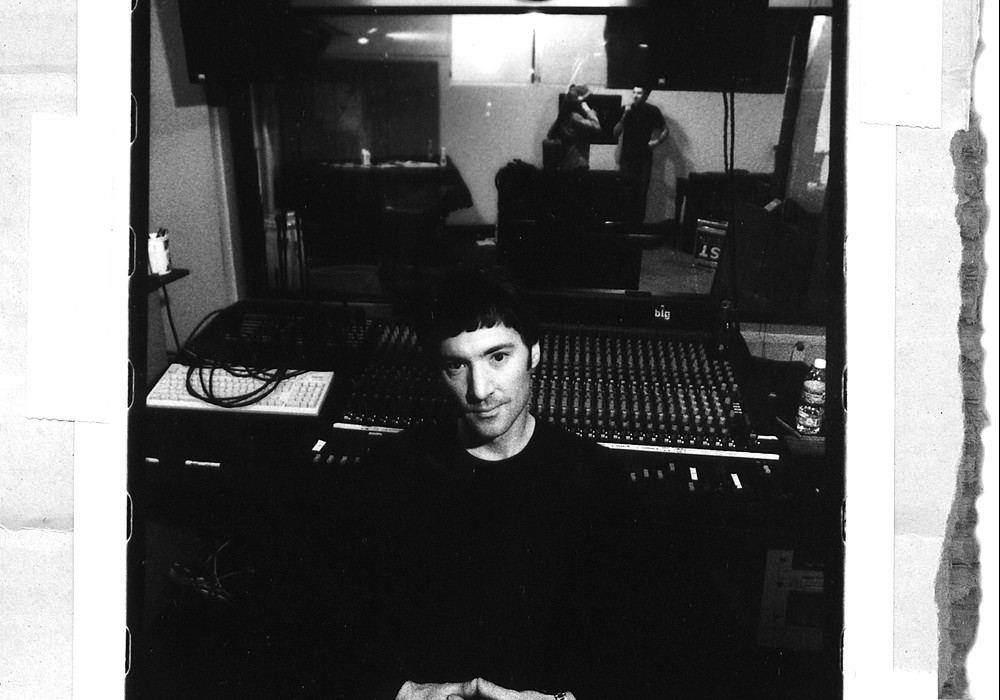

Jeff Lipton is a mastering veteran with an impressive 30-year career under his belt. He's been nominated for four Grammy Awards in the Best Historical Album category, thanks to his extensive work restoring and remastering music for the Numero Group in Chicago. Jeff's journey started from humble beginnings in his bedroom in 1993, and he's come a long way since then. Today, he owns and operates a cutting-edge, two-room Dolby Atmos-equipped mastering facility outside of Boston, Massachusetts. Surviving the turbulent music industry and a challenging economy, Jeff is pushing forward with a new venture that sets him apart from the pack. Jeff is helping artists and engineers who don't have access to Atmos-equipped rooms by having them send him stems. With his expertise, he can optimize their music for the Atmos format, ensuring it sounds its best in any environment. Jeff's character shines through in everything he does. He's a kind and generous professional who's always looking for ways to help others succeed.

The last time you spoke with Tape Op was 20 years ago [Tape Op #34]. A lot has changed.

The music industry has changed a lot in the last 20 years. My clients went from being primarily labels to mostly individual bands and producers. I feel like the industry is in many ways less centralized now; anyone can release an album and have worldwide distribution through streaming services. This change has made good customer service even more important for our studio, as many clients are less experienced with the process or don’t have any team helping them. Also, modern technology has made giving clients more personalized service easier. I now do video calls with every client before I work on their projects. This allows me to get to know the people I’m working with better, wherever in the world they are. It’s so cool to talk to people face-to-face all over the world. For example, I’ve spoken to people in Taiwan, New Zealand, Israel, Scotland, and Germany, and it's like we're in the same room. I find this to be a fantastic format for communication and working on art. Email is acceptable for straightforward requests, but allowing clients to schedule video chats with me at any time during their project provides for much better and personalized communication, which translates to a better master for the client. The last time I spoke to Tape Op, I was only eight years into being a full-time professional mastering engineer. I still had a little bit of my cocky youth side, and I wasn’t thinking about the way I say things as much as I think about them now. I don't believe that it was a problem because I was so young. If I showed confidence, they were like, "Oh, okay. He's wiser than his years." But now, as I'm older, and older than most of the people I work with, I try to emphasize the client experience and set the expectation of excellent communication through the process. I want my clients to feel comfortable reaching out to me about any concerns or issues they have. I also implemented a free revision policy on the mixes we work on, which certainly helps if a project doesn’t meet the client’s expectations. I find 85 to 90 percent of our projects have no sonic revisions, but in the 10 percent that need them, our goal is to do whatever it takes to figure out what the client wants.

Treating it more like a service industry.

Exactly! I feel like mastering is a service industry, and I enjoy the creative relationships I have with my clients. I feel my job is to achieve their creative visions as much as possible. It’s fun to try to think about their material from their point of view. I also think part of the service is setting expectations, and also being truthful about what is possible. I have accumulated a lot of knowledge in my 30 years of doing this. That said, I am constantly learning new techniques for fidelity and problem solving. If a client asks for something I don’t believe is possible, I usually attempt the request to see what can be done. I love that I’m still learning and doing better work all the time. With expertise, there's sometimes having a tough conversation of explaining why doing something a different way might not be a good idea. For example, it might not reproduce as well on specific systems, or there might be other issues with it in ways that a client might not foresee. After I explain something, I will still make their requests if they say, "Okay, I understand that, but I still want to do it my way." I feel that I'm doing a much better job of communicating with people. That's been a massive focus of mine for at least 15 years.

I totally agree. Have you used any tools to stream audio to clients, like Audiomovers?

No. I have yet to try that. I’m not 100 percent convinced that it translates as well to mastering as mixing. With mastering, I don’t feel that real-time feedback is as effective as posting files and allowing a client to audition them on many different systems, and to be able to compare them to other material they know well. I think it’s important to sit with a master and hear how it sounds in different environments. This allows the artist to come up with thoughtful feedback. I’ve also found that the process works better when a client is listening to a master that has been through our whole process. Our process has at least two stages. Every project I work on goes through a quality control stage after I’m finished, where another mastering engineer critiques my work and sends it back to me if they feel changes are necessary. They also will listen for clicks, pops, distracting mouth noises, as well as unwanted distortion that might become more apparent in the mastering process. If so, I’ll remove them with restoration tools. By the time we submit a master to a client, it has been thoroughly checked and should sound as intended. It's hard to get good feedback, even during an attended session with people in the room with me. That said, some engineers are really eager and want me to send something that is not entirely finished. This can be helpful if I'm trying something out of the ordinary, meaning I'm changing things more than I usually do for them, but I feel it's the right thing for the current project. In that case, I'll just print what I’m working on without being completely finished and going through the quality control process. In most circumstances, I think it’s better to post the finished project and do revisions if they are not entirely happy with the risk I took.

Letting people listen in their own environments to sit and be comfortable with it.

It's essential! The pandemic changed the way I do attended sessions. I didn't want to be in a room with someone for ten hours in a row. Now, I typically have everything mostly done when I do attended sessions. Pre-pandemic, as I would finish a song, I'd tell the client to come up and listen in my seat to get their feedback. Then there'd be an hour or two in between, where they have nothing to do, sitting on the couch before they’d come up and listen to the next song. Now I'll have all the songs at the point where they sit in my chair, and they listen all the way through and can give feedback. That's a better end-user experience; it doesn't waste other people's time and makes the best use of the time we spend together.

I would love to talk about the Grammy nominations. At the time of your last Tape Op interview you didn't have any, right?

No. We’ve been fortunate to be Grammy nominated for four different projects we worked on for the Numero Group, a Chicago reissue label. Before working with Numero Group, I did many restoration projects for Rykodisc. Ken Shipley, who founded Numero Group with Rob Sevier and Tom Lunt, heard my work while he worked for Rykodisc. In 2003, I mastered their first release, a collection of songs from the Capsoul label [Eccentric Soul: The Capsoul Label]. Their concept was to find music that was amazing in its time, but that didn't get the attention that it deserved when it was released. I've done probably 60 to 70 percent of their vast catalog. Being a part of the Numero team has been incredibly enjoyable. They are an excellent company, with exceptional taste in music. The first project we were nominated for was Syl Johnson: Complete Mythology. Syl Johnson was this amazing soul singer who started in the '60s. Even in his 80s, he was absolutely amazing. He didn't have much to do with our mastering process, as we only communicated with the label. But it was a thrill to meet him, get to talk with him, and hear his stories. That project was really fun. It was a six-LP, four-CD set. The liner notes are comprehensive and beautifully written. Like most Numero projects, the material came in on tape, vinyl, and maybe some other digital sources. I don't remember exactly. We had to restore everything, fix any issues with the sources, and then make sure all the songs on the six LPs sounded cohesive as an album. This project was enjoyable. There’s nothing quite like cleaning up an old recording so that future generations of listeners can enjoy it. The next project we were nominated for was Ork Records: New York, New York. This is one of my favorite Numero projects. It featured Television, Richard Hell, Chris Stamey, Alex Chilton, The Feelies, and Lester Bangs. It was so cool to work on that material and hear it coming to life again through restoration and mastering. A lot of it was unreleased, or earlier versions of recordings that were released. Of the two remaining Grammy nominations, one was a music collective called Bobo Yéyé: Belle Époque In Upper Volta. That record was mostly music that came out of Africa. Our most recent nomination was for Jackie Shane, Any Other Way. Jackie was one of the very first openly transgender solo artists in the ‘60s, and during this box set you hear her voice change from male to female. Her songs are incredible! I was blown away by how great Jackie’s songs are! We never met Jackie; unfortunately, she passed away soon after the Grammys in 2019.

I want to shift into Atmos.

I’m excited to talk about Dolby Atmos. It’s been enjoyable to learn how to master music in a new format. What makes Atmos so exciting is that this format works with as few as 2 speakers, up to 64 speakers. For the listener, all they need to do is stream music mixed in Atmos to an Atmos-compatible system, and the system will decode Atmos correctly for their environment. The regular stereo version will be used if they don’t have an Atmos system. This simplicity and scalability make Atmos much more straightforward for listeners to use and enjoy than previous surround sound formats. Compared to 5.1, I feel Dolby handled this much more intuitively and better for the consumer. The consumer doesn't need to know anything or do anything to listen to an Atmos mix, they just need to turn their device on and stream to play. Atmos also has some cool features: 1) Atmos requires that no mix can be louder than -18 dB LUFS integrated. If the material is louder, it’ll be rejected from the streaming platforms. This is huge, because the format will effectively end the loudness war and allow music to be heard with much more space and clarity. 2) Atmos mixes must correspond to the stereo mixes. They need to be the same length and have the same fades as the stereo versions. 3) Atmos allows mix engineers to use objects that have their own panning. These objects, or tracks, stay separate inside the Atmos ADM BWF master file. This allows the decoding system to reconfigure the mix to work best in the listener’s environment, preserving as much of the essence of the mix as possible. Some people think it was crazy for me to make such a huge investment to be able to work with Atmos. My thinking was to make the investment so that the mix engineers that I work with won’t have to, but will still be able to offer Atmos to their clients. I’ve found that I can make excellent spatial mixes from stereo mix stems. Not only are these mixes much more spatial, but they also stay true to the stereo mix. In essence, I’m just spreading out the stereo mix while often automating a few tracks that make sense in context. I’m also helping mix engineers who would like to do the Atmos mixes themselves do them in my room. I’ve also even had good experiences mastering Atmos mixes that were mixed on headphones. I was skeptical that this would work, but some engineers I know are making great surround mixes this way. Starting with [Avid] Pro Tools Ultimate 2023.12, the Dolby Atmos renderer is built into Pro Tools, giving many more engineers access to this technology. Of course, I’ve had the pleasure of mastering many Atmos mixes that were mixed in true surround. That said, with all the different ways that Atmos mixes can be made, it becomes even more important to implement excellent quality control in mastering. It’s important to make sure that there aren’t any phase issues when a mix is played in 7.1.4, 7.1, 5.1, or binaural stereo, as well as testing the mixes with Apple products, which use Apple’s spatial decoder. The mixes need to fold down and open up, without losing their integrity.

When was your Atmos studio completed?

The acoustic work was completed in 2021, but then it was a process of getting all the gear to work correctly and figuring out how to work in the new format. The room has been fully tuned and active since June of 2022, but I didn't complete any projects until August because I wanted to experiment and figure out what I was doing. I'd say the greatest resource for figuring out Atmos are videos on YouTube by Andrew Scheps [Tape Op #133] on Puremix. He has two videos on it. One is him discussing all the different technical aspects of Atmos, and then there's another one he did with four other engineers: Greg Penny, Steve Genewick [Tape Op #150], Fab Dupont, and Dave Way. I've watched these videos multiple times. They are excellent resources!

It's amazing! I’ve seen it too. Does working in Atmos feel like a completely new thing to you, or is it coming naturally?

I’d say it’s mostly coming naturally to me. I’ve come up with some robust Atmos workflows and worked with my team to create a decent amount of quality control on our projects. Atmos is a lot more complex than stereo. As I mentioned before, there are objects, which are separate tracks, or groups of tracks, that you can pan anywhere; and there is the bed, which consists of 10 channels. A mix engineer can decide whether to keep the objects separate, mix in 7.1.2 to the bed, or use a combination of the two. That said, working with the bed and objects is very different. Mastering the bed is closer to mastering a stereo mix. But objects are new because, obviously, in mastering stereo, I'm never just working with a guitar track, just drums, or so many separate elements. Just like working in stereo, my job is to enhance each song to sound its best and work together with the other songs on the project. When working on an Atmos mix, I can still use a combination of my analog and digital gear. This works exceptionally well for stereo objects. Often, I can use settings similar to those that I use for the stereo mix on the Atmos mix, which, while time-consuming, is incredibly useful.

So, you can still use your hardware?

I can still use my hardware, which is amazing! The important thing is to make sure none of my gear changes the phase correlation of the different tracks and objects. I check all my Atmos masters in 7.1.4, 7.1, 5.1, 2.0, and 2.0 with Apple products to verify that there are no phase issues. Apple has a different decoder than Dolby for playing back the Atmos mixes.

Is that a new thing?

From what I’ve read, Apple worked to come up with a decoder that they think works better with their products than Dolby’s decoder. It might really be that they didn’t want to license Dolby’s decoder. Who knows?

Listening to Atmos music on my Apple AirPods was the thing that made me start to believe this could be viable for consumers.

Yeah, it does sound great! I often find that the stereo version of an Atmos mix sounds better than the stereo mix. I assume that one of the main reasons is Atmos requires that every Atmos mix is -18 dB LUFS integrated. This means that Atmos mixes have so much more dynamic range than almost every stereo mix. Most stereo mixes I receive for mastering are louder than -18 dB LUFS integrated. Dolby had to make the standard this way so that the Atmos masters would scale up and down to suit the environment used for playback.

Was there a particular moment you knew you wanted to work in Atmos?

I saw all the buzz around Atmos on the internet, which I found intriguing. When we started building the current Peerless in 1999, 5.1 was the exciting new format. I decided to spend a ton of money to make my room acoustically accurate for both stereo and 5.1, as well as buy five full-range custom speakers and amplifiers. At the time, there were two new formats, DVD-Audio and SACD, which, for the first time, allowed for high-resolution releases in both stereo and surround. Unfortunately, around the same time these new formats came out, the internet started becoming mainstream, and consumers were more excited by low-resolution MP3s that could be transferred between computers. The 5.1 work completely dried up around 2009, but even before that, getting projects in 5.1 was a novelty. It was a bummer. When I initially started reading about Atmos, I was skeptical that it would become a new standard. However, when I saw how much time Apple was dedicating to spatial audio at its product announcements, and how many of their products were Atmos compatible, I decided to go for it. Apple rarely embraces a format and then abandons it. I figured that since my room was already designed for 5.1, it meant just adding four speakers in the ceiling, as well as two additional side speakers. I thought it would be an easy upgrade. It wasn’t. The project ended up taking four to five weeks to modify the room to work in 7.1.4. This included adding the six new speakers and redoing the acoustical treatment behind the cloth walls and above the ceiling to work accurately with the new configuration. My acousticians worked with Dolby to ensure the room met their specifications. In the end, the room sounds great in both stereo and Atmos. The acoustical changes ended up making the room even more accurate and easier to work in. So, the short answer is that I felt like Dolby made Atmos easy for consumers to use, and since big companies like Apple were embracing the format, I saw it as a possible draw for the studio, as well as a format I would enjoy.

Do you think it's more accessible for people because of headphones with Atmos capability, and the streaming services handling it?

Yeah, definitely. Dolby made it easy to hear music in Atmos. Atmos devices do all the work, handling all of the down mixing, up mixing, or whatever needs to happen to make it sound the best it can on the device that's being played back on. Dolby also certifies every device that says it can play Atmos, ensuring it lives up to their specs. Dolby is very hands-on with the format and is doing an outstanding job.

Sometimes I realize I'm listening to the Atmos version of something on my AirPods without even knowing.

Yes! I think many consumers do not even realize that they're listening to Atmos and getting a better listening experience from it. Atmos is being added to new devices all the time. A lot of TV sets now have Atmos compatibility built into them, so they'll decode Atmos when you're streaming through your set. I do this in my living room when I'm home. I know that sounds lame for someone with a great listening environment at my studio, but I find it interesting to listen to audio through consumer devices outside of the studio. It’s a great way to test my work, but it’s also interesting to hear how music generally sounds through these systems. Also, it’s cool that Atmos doesn't require us to mess with our living spaces to listen to it, especially if it's coming from your TV. Also, companies like Sonos have done a great job of implementing Atmos. You can put the system together piecemeal over time. If you start with their sound bar and then want to put rear speakers, or even ceiling speakers, you can add them and Sonos will reconfigure the Atmos decoding and playback for your setup.

That's one of the coolest things about Atmos, not being tied to a specific set of speakers or listening experience. That's one of the things that that 5.1 did not have.

And that's why I think 5.1 absolutely failed. It wasn't a consumer-friendly format, as it required speakers to be set up rigidly, which didn’t work well for many living spaces. People seem to love Atmos when they hear it. I've been playing Atmos in 7.1.4 to pretty much everyone who visits Peerless these days. I love playing it for people who have nothing to do with audio engineering and then watching their reactions. Though, even most audio engineers are floored by how great it sounds. One of the most fun reactions was from a 19-year-old visiting the studio. She said it made music sound the way it sounds when she’s stoned. [laughter] One of my favorite Atmos songs to demo is Elton John's "Rocket Man;" it’s one of the best Atmos mixes, in my opinion. It was mixed by Greg Penny, who did such a thoughtful and beautiful mix. What’s so great about it is that it sounds like the stereo version, but everything is much clearer and accessible. It both feels like the song we all grew up listening to, but it also has so much more dimension. When I play people Atmos for the first time, people’s eyes light up and they feel the magic of the music. It’s so cool. Even people who feel they don’t care about audio quality are drawn in.

One of the other things you've been doing with the new Atmos setup has been inviting mix engineers and producers from around town to use your room to mix in. How has that been going?

Working with mix engineers in my room has been so much fun. Once I provide enough instruction for them to be up and running, watching what they do with the format is so interesting. This was always the plan. Since it’s so expensive to design and implement an Atmos room, I wanted to be able to provide my room to mix engineers who want to try mixing in Atmos. Or I can help make great Atmos mixes from their stereo stems, which will keep the integrity of the original mix. Engineers can send me stems of their stereo mix, and I'll work out an Atmos version for them. Engineers are welcome to come to my studio with their sessions and rework the stereo mix into Atmos. It's been exciting to do mixes both ways! Some great Boston engineer/producers, such as Brian Charles, Sean McLaughlin, and Benny Grotto, have worked in my room on Atmos mixes. Most of my clients are too far away to come to Peerless to mix in my room. However, I’ll make Atmos versions of their mixes if they send me stems. I’ve been doing this for clients all over the world. I can make great Atmos versions of their mixes. Technically, I’m mixing, but I think of it more as adjusting the panning/placement of a mix while keeping the levels and balance of the stereo mix. I'm placing sounds or instruments in certain places. And sometimes I'm doing a little bit of automation, if it's something that the artist wants. To me, a good Atmos mix is true to the stereo mix. I don’t think using all of Atmos’s bells and whistles is necessary for something to sound good. I also don’t think it was Dolby’s intention to have Atmos mixes be too different from the stereo mixes. Different instrumentation shouldn’t be in the Atmos mix, versus the stereo mix. It will be rejected if you submit it and it's not exactly right to their specifications. I think Atmos is great at enhancing an already great mix. When I do an Atmos mix from stems, it ends up feeling like the stereo mix expanded and spaced out, so all the instruments are clearer. For example, I worked on a Tucker Martine [Tape Op #29] mix in Atmos. His mixes are phenomenal, and his Atmos stems were great. They already had most of his processing on them. It wasn’t a lot of work to process stereo stems through the stereo mix mastering settings, change some panning, automate a few instruments that already had movement, and make them into a great Atmos mix that had the same feel and levels of Tucker’s mix. I don't feel like I mixed this song; I feel I mostly did the mastering work.

Does your mindset have to change a lot when you're doing that?

It feels so natural, because I usually have mastered the stereo mix when working with the stems. So, I already know the song well and I know how it sounds in stereo. What I'm doing is like stretching out the stereo version and keeping it accurate to the essence of what came in. I feel that that's the best approach on my end, as I’m not a mix engineer.

What's the best way for an artist or an engineer to prepare for you to make an Atmos version of their stereo mix? What are all the things you ask for? And what should people be thinking about if they want to take their stereo mixes and bring them into this format?

First, make a really good stereo mix. Then, it’s important to print the essentials to separate stems. If it’s a rock song, printing separate stems of any element of the mix that will sound good in its own space is a good idea. Some engineers print stems with the effects already on them, and some send the effects as separate stems. Usually, it’s best for me to have 15 to 30 stems to be able to make a good Atmos version. It’s good to have the original effects so that the Atmos mix still sounds like the stereo mix. In some Atmos versions, I've added a tiny bit of reverb, and sometimes I've used interesting plug-ins that convert stereo stems into 7.1.4. It can also work well with less complex music. I was asked to work on an ambient new age meditation piece. It only had three stems/tracks in total. I ended up using the Nugen Halo Upmix to convert the three stems to 7.1.4. The Nugen plug-in offers a lot of control, and I was able to make an Atmos version that sounded all-encompassing while still being true to the stereo mix. Halo Upmix was designed to keep correct phase in Atmos, which made this even easier. The artist said that for her genre Apple requires an Atmos version. Apple also recently announced that they will double the royalties on a song that is submitted with both a stereo and Atmos version, which could be huge for artists.

Are you finding it easier for engineers to make stems now that so many people are mixing in the box and using automated tools, like SoundFlow's Scheps Bounce Factory?

Yes, it's so much easier now that artists and engineers can automate these processes and create stems without manually bouncing every stem. These tools are invaluable for mix engineers. Stems are becoming mandatory, because many labels now ask for stems to be submitted with the stereo mixes for every project. These tools make this request so much easier and possible. It's also helpful for mix engineers who are still using analog gear. Unless they print stems, they can't do a perfect recall. But, with stems, they can make minor tweaks to mixes anywhere without even having access to the analog gear.

I don't know that you would be working in this format right now if we didn't have some of these automated tools. It's so time consuming for engineers to print all of the stems that you'd need to make a great master.

I agree. Though, some engineers have been using interns and assistants to make stems or alternate mixes for years. These tools make this much less labor intensive.

Are more clients asking you to work in Atmos? Or is it engineers asking?

Many of my label clients are asking about Atmos. But many indie clients, artists, or engineers, don’t know what it is yet. Many haven’t yet heard Atmos. I’ve been working to change this, and allow indie artists and engineers the opportunity to hear their music in Atmos. In all of 2024, I made an Atmos version of a song for free if we are working on a stereo project with four or more songs. We also did this in 2023, and it was a huge success. People enjoyed learning about Atmos and spatial audio, as well as being able to release their music in this format at no extra cost. Moving forward, I'm hoping to partner with engineers from all over the world – especially indie engineers – to provide them with Atmos mixes for their clients without them having to make the investment in Atmos. This has all been super fun and exciting! I'm always looking for a new challenge. That said, working in stereo is still exciting. I feel like I learn new things every day. And Atmos is just a whole new thing where I'm always learning so much, and I'm excited to see where it goes.