Quaintly nestled in the western region of upstate New York, USA, between Buffalo and Erie, Pennsylvania, lies a small blink-and-you'll-miss-it town named Cassadaga; a place where maybe the most exciting thing going on might be someone filling up their vehicle with gasoline. While existence in any small community may lend itself to being very quiet and seemingly uneventful, Cassadaga in particular, just so happens to be summoning some of the world's most acclaimed musical recording artists. The source responsible for the phenomenon points towards nearby Fredonia resident Dave Fridmann: producer, recording engineer, musician and an overall friendly collaborator. His perogative is different and simple — to fill up tracks.

Young Dave first hits 'Play' — the button with the arrow that points to the right.

The genesis for Fridmann's involvement in the recording arts originated from his days as a high school student in his native Buffalo, New York, suburb of Williamsville. And like many suburbanites beaming with a jaded-less sense of unlimited hope for a stable and fulfilling future, he made up his mind on what he was going to do. "Like most recording engineers, I wanted to be a rock star," he muses. "I became aware of engineering during my junior high school year through my music teacher who was an alumnus of SUNY at Fredonia. He had heard that they started up a new sound recording program and thought that I might be interested in it." Upon graduating from the binds of high school, Fridmann enrolled in the program to continue his pursuit for rock star luminance. "It seemed to me, in a very viable and obvious way, that if I wanted to be a rock star, the best way to do that would be to meet other rock stars, and the easiest way would be to become a studio engineer because that is where rock stars were. That's one way to get in."

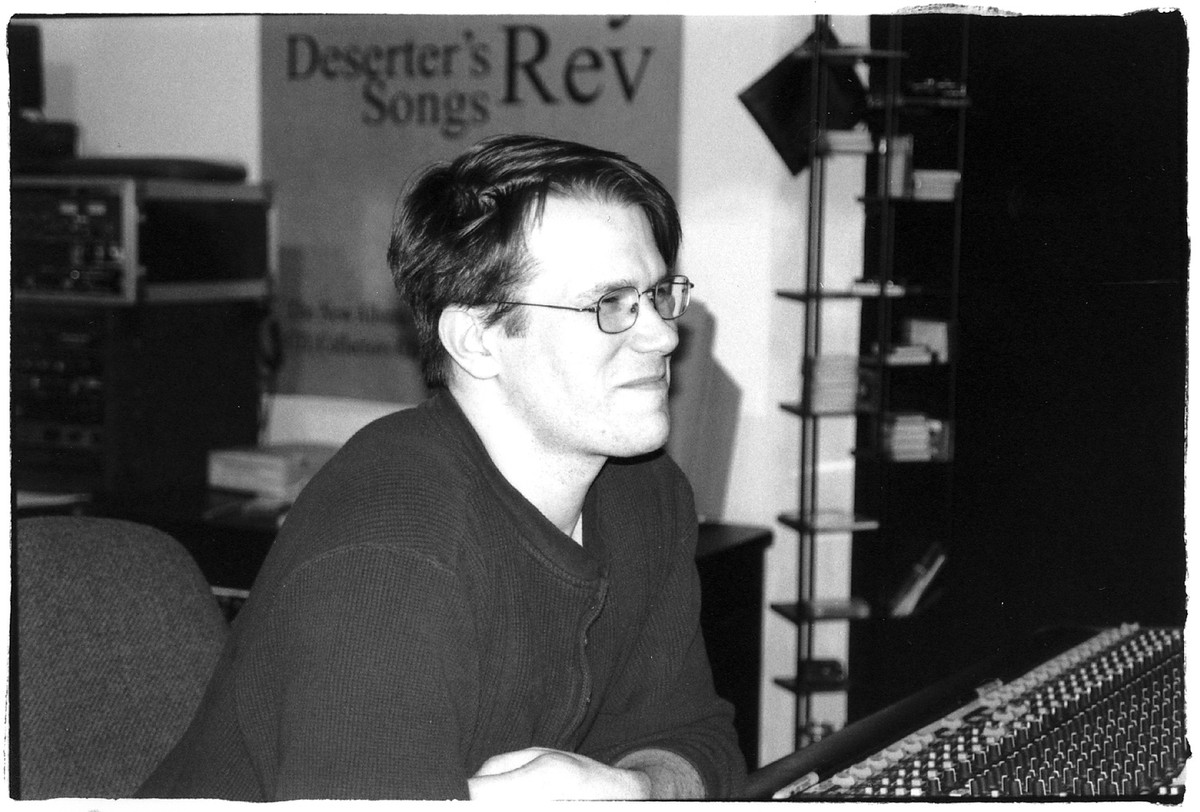

Fate or coincidence. Depending on whichever belief system the reader leans toward, it was certain that Fridmann would find himself in a situation that would surely propel his desires into reality — in the role as bass player for a band. "In a lot of ways very much exactly what I hoped would happen did happen," he states matter-of-factly. With access to the college recording facility's Amek Angela console, Otari MTR-90 Mk II 24-track machine and a band called Mercury Rev [interview], he would get a chance to exercise both his ears and his bass playing. "When early incarnations of Mercury Rev came into the studio to record they didn't have a bass player," he recalls. "I would record their songs and then we'd get to the point when we'd notice, hmm... gee... we really should put some bass in there, which would be left to last and then I'd say, well, 'I could play it 'and they'd say, 'Okay, go ahead!' I ended up joining the band which worked out exactly as I'd hoped, which wasn't as it exactly turned out to be what I wanted, but that's what I thought I wanted at the time so it worked out great." The resultant product of their first collaboration was 1991's Yerself Is Steam, featuring the stratospheric "Frittering", which was primarily recorded at the college and mixed in Argyle, New York, at Sweetfish studio.

Two more collections of songs were transduced onto tape by Fridmann via the college and Sweetfish studios combo; In A Priest Driven Ambulance and Hit To Death In The Future Head, two albums by a band equally and colorfully known as The Flaming Lips. He recalls how he first became acquainted with the Oklahoma-based group. "Jonathan [Donahue] from Mercury Rev went to college in Buffalo and was a promoter there who became friends with The Flaming Lips and eventually became their tour manager. He'd be on tour with them and couldn't really do their live sound well and once they could afford a live sound person, he asked me to do it. By then I had been doing Mercury Rev stuff for a while. At the end of their first tour I knew they were going into the studio and I built up enough courage to tell them they should do it with me. They fell for it, and we ended up doing it and we have been mostly ever since."

During this formative period Fridmann began to apply a certain polishing touch and character to Mercury Rev's final product via a now nearly deleted medium — magnetically striped 35mm film. "Back in the 1950s, 35mm magnetic film sounded better than what was normally available at the time in the world of music technology," he quips. "Some of the old Miles Davis and other jazz stuff were tracked onto that simply for the fidelity. It was a more durable medium as well. That was the inspiration to use it. I thought, hey, that sounds pretty damn good." Ever since first applying that process to the mastering of Yerself Is Steam, 35mm magnetically striped film became a staple of every Mercury Rev album.

"Jonathan actually used to be in The Flaming Lips (under the alias 'Dingus') and we've demo'ed songs for the Flaming Lips that ended up in the long run being Mercury Rev songs," he reveals. "It's a very incestuous relationship. There's been times when both me, [Mercury Rev guitarist] Grasshopper, Jonathan and The Flaming Lips have all been in the studio at the same time working in the same music." Not only does Fridmann write with both bands, he also aids with constructing arrangements as well. "Everyone has a lot of common ideas as to what is good and what constitutes good sounds. It's no accident that there are a lot of similarities."

When time came for Mercury Rev to tour and promote themselves worldwide, Fridmann chose to bow out of touring duties. Unlike musical artists of the past such as Syd Barrett and Brian Wilson, both being brilliant yet too detrimentally preoccupied with mental 'crutches' to take on touring, Fridmann was far from being a semi- dysfunctional person. Instead, he opted to stay in the US and work with an array of groups including Syracuse's The Wallmen, Jennyanykind, St. Johnny, Grand Mal and Weezer.

The filament burns bright.

In a blessed 'right time at the right place' situation during the summer of 1997, Fridmann found himself temporarily exchanging his natural habitat for a big learning lesson in the madness that is known as Los Angeles, California. His task was monumental — to co-produce a new track entitled "So What!" for Kettle Whistle, a compilation disc by Jane's Addiction, a band that is infinitely distant from 'normality'. "No one wanted a normal sounding set up, so Kevin Haskins from Love and Rockets (a friend of Jane's Addiction's Stephen Perkins) brought in his home studio gear that included samplers and I also borrowed a series of guitar pedals called Love Tones from Joe Barresi." Barresi, an engineer/producer in his own right, first met Fridmann in 1996 during the Weezer Pinkerton sessions, remaining great friends ever since. Fridmann considers Barresi to be the best engineer he knows, someone from whom he has learned a lot from. Fridmann continues, "I ran the drum loops through the pedals. It was the first time I ever experimented like that especially with something that was so loop-based."

Fridmann also had another concern, a large sized one. "I was very worried about how I was going to get Dave Navarro's sound [Jane's Addiction's guitar player]. I always thought he used some special big rack of gear to get his sound, but instead he shows up to the studio with only a Marshall half-stack and a few pedals. I sent the assistant to mic his amp with an SM57 and didn't even see where he put it and all of a sudden blaring over the speakers was 'DAVE NAVARRO'. And [singer] Perry Farrell became Perry Farrell screaming through an SM58." This was actually first experienced during the sessions for the second Mercury Rev album when John Ashton of The Psychedelic Furs [guitarist] was invited to play on the album. "He came straight from England to Buffalo with absolutely nothing and played only through our gear and he still sounded like The Psychedelic Furs." Fridmann excitedly expands on what he calls a major "revelation" on the Jane's Addiction incident. "What was even weirder was when Flea [from the Red Hot Chili Peppers] played bass. At one point I wasn't looking and Flea handed over his bass to Navarro who started to play it. I wondered to myself why all of a sudden the bass sounded like crap. Then I found out why. Navarro handed the bass back to Flea and all of a sudden it sounded great again. I really didn't have to do anything. The sound literally came out of his fingers!!! The sound was him."

Badminton anyone?

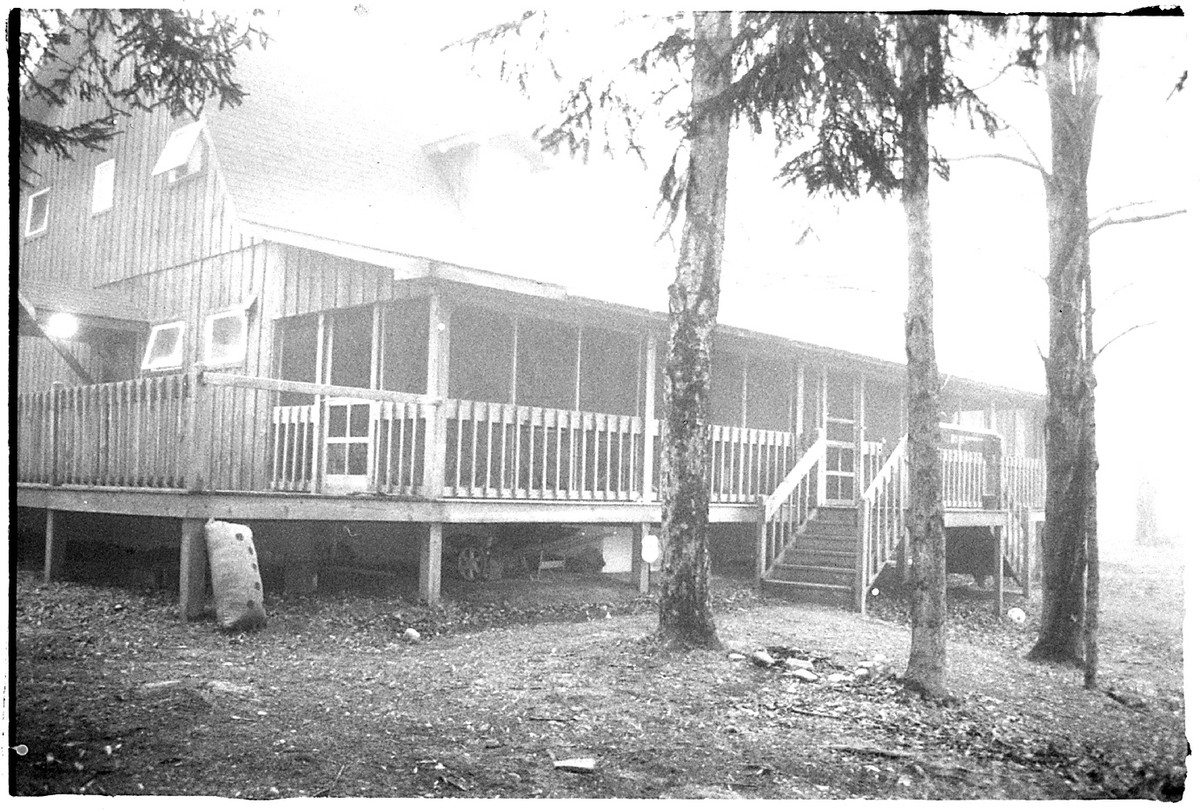

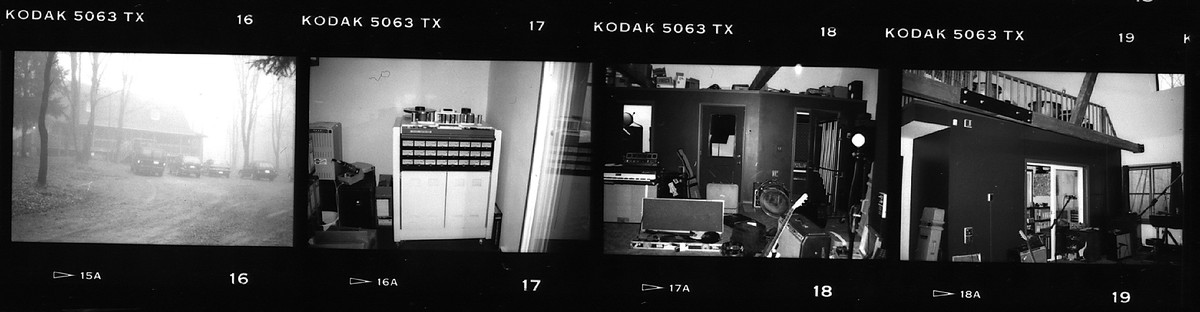

Once Fridmann's personal world expanded into a family unit, the idea of having one conveniently fixed studio close to home where a project can be realized from start to finish became yet another logical idea. Hence in the summer 1997, he, his wife Mary and additional partners Greg Snow and Andrea Wasiura erected what is quickly becoming a mecca for many recording artists — Tarbox Road Studios. Inspired by Sweetfish studios, Tarbox Road is located in Cassadaga a capillary town of Fredonia. The isolated cul-de-sac studio-in-a-house is far from its deceptively rustic shell as it boasts not only creative autonomy, but also allows a client to practice their badminton skills for recreation purposes if they see fit. It is a place to work that is situated in Dave's preferred rural setting, serving as a place to nurture focus on the work at hand, far, far away from any intrusive big concrete city music 'industry' types. "What I shoot for most of the time is to get clients comfortable just as if they're at home working on their 4-track at 3 AM at their own pace. I may go home at midnight, but I'll leave 2 mics and a DI set-up and tell them what tracks they can record on. It doesn't take a genius to hit play and record. It's a great environment. People just work. They come down [from the studio's bedrooms] the next day in their pajamas and keep working, just like home." The location also tends to make sure that a project maintains 'freshness' to avoid 'studio burn out', or worse, an age-old condition known as 'cabin fever'. "Most bands get sick of being in the sticks, bands tend to record here only in two week segments" he chuckles since that environment does not phase him due to residing in it for a majority of his life. For a Japanese band like Number Girl who came straight from Tokyo to Fredonia, one can imagine the culture shock.

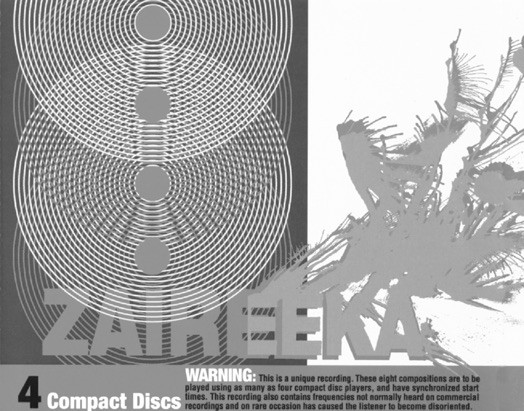

The first project to deflower the new facility was instigated by The Flaming Lips' Wayne Coyne. It was to be a 'modest' project, one that would only involve the creation of four separate compact discs that were meant to play through four exclusive sound systems at once, and whose purpose was to shatter linear storytelling by taking the listener into a new dimension of time and space. It was called Zaireeka (the combination of the words Zaire, an idealism inspired by the country's state of disarray and chaos; and Eureka, the word Coyne used to describe a sudden discovery of an idea that moves forward the creation process. "We weren't sure what would work... we set up Tarbox with Zaireeka in mind," Fridmann recalls. "Greg [Snow], who does the tech work here, set up four sets of speakers and four DAT machines. We bought an [80 input] Otari Concept Elite console, which has flexible routing features and is massively automated. We chose it because it would work for Zaireeka the way it is... so it would be possible to do all four live simultaneously. He made this really cool box with 4 stereo faders connected together to control the playback level. It looked like an airplane thruster." An example of what goes on with the psychotropic Zaireeka is perhaps best depicted in the track "Thirty-Five Thousand Feet Of Despair", which sonically tells the tale of a troubled airplane pilot who commits suicide in the middle of a transatlantic flight. Each disc contains a different perspective of the situation at hand. Disc 1 features a news reporter who awaits the landing at the airport, disc 2 has the pilot walking to the bathroom to meet his demise, disc 3 contains the downtrodden airport ambiance and disc 4 goes subjectively deep inside the mind of the angst-ridden pilot. As one might rapidly come to the conclusion, Zaireeka, now sadly out-of-print, is definitely not your everyday standard generic top 40 kitsch.

Their method of taming a behemoth of a project was approached with a need to maintain sanity somehow. "In general we mixed each CD one at a time so as to have more randomness so things wouldn't sound too perfect. The final product [the CDs]were easy to synchronize but DATs aren't. Most of the time we were listening to it very poly-rhythmically. It was a strange event. It plays more normal for the people who listen to it now than it was for us. We thought it was weirder, which of course, we thought was cool." In an attempt to sync the aural information so as to have things not be led too astray, Fridmann included a time cue in front of the tracks, similar to a slate used in filmmaking. "We did the mastering at the studio just to make sure there wasn't any confusion down the line." In the end, the experiment was deemed a success, and is now a staple for many who enjoy being taken on a ride to previously uncharted territories of perception. It also makes for great entertainment at parties and by no doubt is highly suitable accompaniment to those who enjoy ingesting substances.

On any given session, be it Mogwai, Home, Delgados, Citizen King, Creeper Lagoon or Toronto's Bodega, Fridmann assesses that the top 3 microphones responsible for picking up the soundwaves from instruments are the tube-based Neumann U47, the RCA 44 ribbon mic and the common day workhorse known as the Shure SM57. Before the gracing signal paths with the warm and omnipotent U47, a pair of Neumann TLM 170s were constantly employed around the clock. "When I finally got the chance to use a U47, I was shocked and appalled over the superiority it had over the 170s," he excitedly reports. When he occasionally ventures to another studio to work, he is sure to pay attention and always keep on the lookout for new mics to induct into the Tarbox tour of duty. Among the ones desired are the Earthworks Omni OC1 and the Coles 4038s, of which he professes would accumulate quite a bit of sonic mileage at his studio.

Dave can see more things that should be heard.

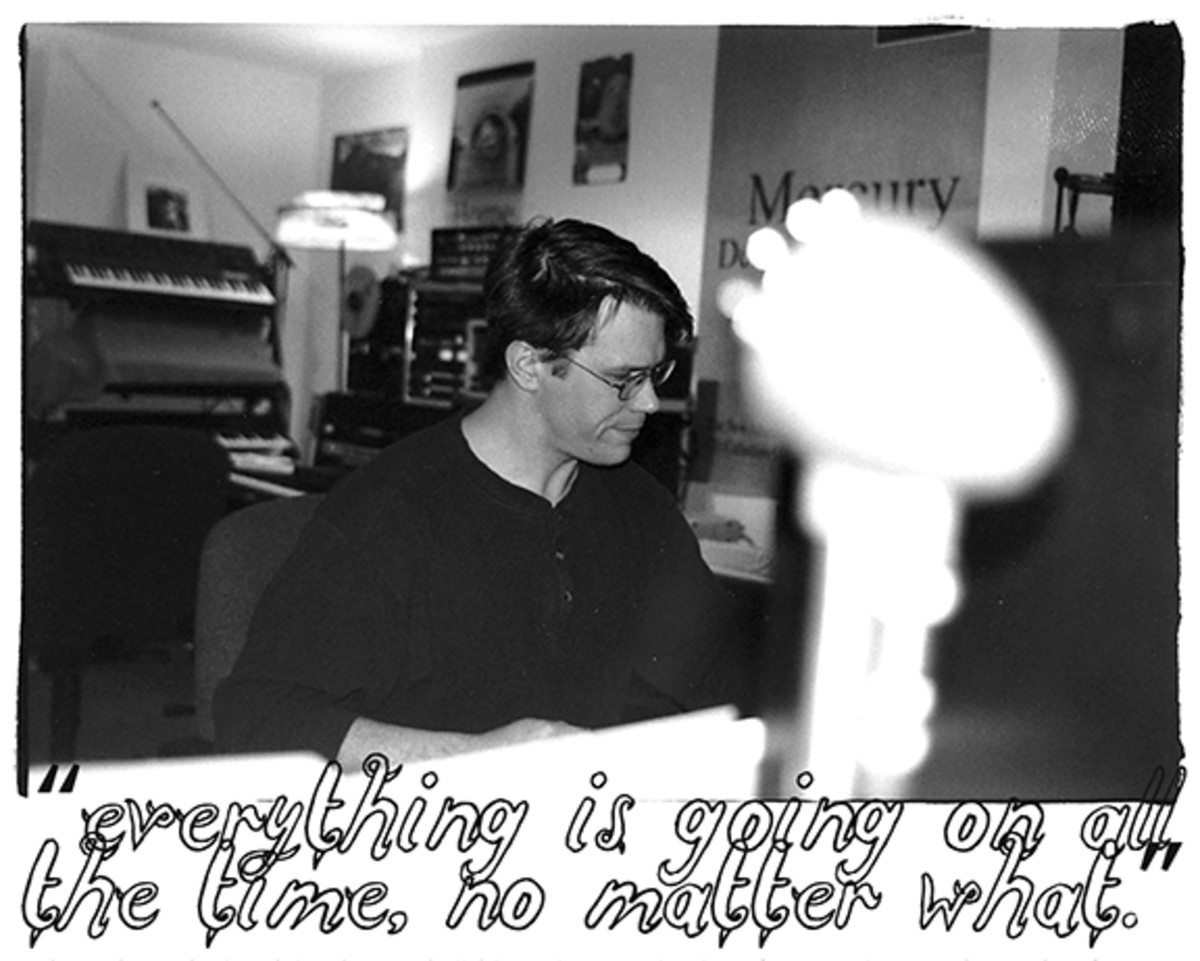

Fridmann also believes in ghosts. Well, sort of. When a client records at Tarbox, their project is subjected to every morsel the facility has to offer. The sounds emanating from a guitar amp for instance, can interestingly transmogrify into a haunting sound in one of the far corners of a room. And just in case something does go there, a mic will be present to capture the stray sound. Nothing is nothing, not "nothing is everything" as someone once preached. "I always have both of my 24-track MTR-90 II and RADAR Otari's running at the same time. There is no reason not to use them. I have everything going all the time due to the nature of the bands I work with. Most of the projects I work on are 'studio projects'. We're not sure what it is going to be until it's done. We put things down one by one then sometimes do it all over again because minds tend to change so much. Or, you get to the point where you realize what you should have done and you start over and keep going and going. Even the simplest things I do now tend to be 48 track. Number Girl are very straightforward and play together, which is uncommon for what normally goes on with projects I work on. They're adamant about recording live at the same time and that will be the final take. If it's not good, we'll keep doing it until it is. And even with them I am into the second 24-track. I set up a million mics, arm all the tracks and fill 'em up. I may end up using two mics in the long run, but I always like to have options. You never know what might happen." In what is beginning to sounds like his motto, he cannot help but ultra-emphasize his strict recording regiment in which "everything is going on all the time, no matter what."

ADD — Analog vs. Dave vs. Digital.

"When [Digidesign] Sound Designer and ProTools first came out I wasn't leery of them at all," Fridmann reassures, keeping in tune with his ever-accommodating persona. "I wanted to embrace them but they sounded like crap. In general, I prefer analog, although 24-bit [digital] is pretty amazing now. We did a jazz band [the Steve Copeland 5] entirely on the studio's digital 16-bit Otari RADAR simply for financial reasons because it costs only $15.00 to back the data onto a tape. While we were tracking, Dave runs, Fridmann found what he considers are the best tape stocks to load his multi-tracks and magnetically charge their oxides with. "These days I stick with the revamped Quantegy GP9 formulation because it's reminiscent of the old silky 3M 996 formulations. It has more of an in- your-face rock sound whereas 499 was a little rougher like 456. I still use both depending on what the project calls for. I still don't like BASF. I can't figure out why people do."

It's always inevitable.

Fridmann and his collaborators will at one point be left to think what should be right for a mix that gets piped down the 2-track digital highway. "Before outboard converters I used to pick flavors of DAT machines like picking flavors of tape. I still hate Panasonics because they're too soft sounding. From memory, even Tascams were better, because they at least had a crunch and attack — you could really drive them." When it came time for Fridmann to go to the DAT machine 'toystore' for Tarbox he purchased two Sony PCM-R500 with SBM (Super Bit Mapping). "By default, I thought they sounded best on their own, especially with its D/A conversion. However, I haven't used built-in converters in a DAT machine in a long time." This is because Fridmann massages his projects with his older model TC Electronic Finalizer for A/D conversion with no compression or normalizing. Since 16-bit is still the all-around standard for digital, he sticks to it. His Pro Tools is 16-bit as well, but soon plans to upgrade to 24-bit for archiving. He would love to see 24-bit become the standard. "Even a person who isn't obsessed with sound will be able to tell the difference. The sampling rate should be left at 44.1 kHz, because the 96 and 88.2 rates are kind of a hoax. Sampling rates don't matter as much and are not anywhere nearly as important as bit depth is. They should focus on that more." He also confides his view on 1:1 digital copies or 'clones'. "The difference is terrible. It's as plain as day."

And while a band might be discovering new heights of musicianship thanks to Fridmann's friendly work methods and Tarbox's comfy atmosphere, he himself can be found in a perpetual state of seeking technical enlightenment. His concerns these days are cleanliness of the sound kind. "I've been worrying a lot about noise lately. It's a private little fetish of mine. I've been testing out various sounds versus noise combinations. I'm trying to find a quiet dynamic mic so I can use my older Altec mic pres. Even with my RCA 44, it's hard to get an adequate amount of gain without noise creeping up." Although he once temporarily discovered relief via the use of a Summit Neve Element 78, he feels there is a more universal way to go about it. The quest continues...

Dave reaches the final stage — with ease.

When possible, every stage of a Fridmann- related project is executed at his studio to be kept free of possible 'contaminants'. Keeping with the Fridmann tradition of logic, he puts his foot down. "Let's put it this way — a lot of what I do as a producer happens in the mix stage. When it says 'Mastered By Dave Fridmann' it means we didn't change anything. When we do a mix, it's done. It doesn't need anything else. At the end of any mix session I print a CD-R and it has to be as good as a finished CD. If it's not, then keep mixing, 'cause it's not done yet!" Eloquently put.

When queried whether he is a producer that is noted on the outside for working on projects that are more suited for 'connoisseurs', Fridmann takes a moment of silence for introspection before replying. "Sure, there is a cinematic scope to most of the projects I work on," he admits, "I naturally gravitate towards those types and vice- versa." (He also admits to the hopes of taking on sound design duties for films in the future, taking his passion with 35mm film a step further). "All people seem to care about in the big picture is 'the beat'. The guy who fixes my car knows I do something with music and asks me whether I heard a certain song because it had a good beat. Once you get beyond record sales of 20,000 copies you start getting into the 'normal people' audience very quickly. All the work and intricacies that you've put into a recording just doesn't matter anymore. People don't care. They only want to wash dishes or party to music. That's fine, I don't have a bias towards that. A lot of stuff I've been working on recently certainly has been 'weird' in nature, but we're hoping that it can appeal to a wider audience. There is a concerted effort to do that." And with the success of The Flaming Lips' The Soft Bulletin, they are obviously on the right route.

Suddenly everything has changed.

When the calendar year rolled into the infamous digits that read '2000', numerous music-related publications world wide began to report that The Flaming Lips' The Soft Bulletin as the 1999 record of the year. Featuring such lush tracks as "Race for The Prize" and "Waitin' for a Superman", the on-again-off-again 2 year project was a labor of love of which everyone involved on the project will attest that it was an intense learning experience. Initially the album was planned to exist as two separate versions. One would be inspired by the positive results of Zaireeka format which allowed for them to potentially use all 80 tracks that were sometimes going on at once. The other mix would be what is currently available, a stripped-down stereo version. Fridmann warmly sums up his experience working on the critically acclaimed album. "To me, the best thing about The Soft Bulletin was when there was this time period where we weren't really sure what we were doing. About a year and a half into the project we were recording the track "Feeling Yourself Disintegrate" and did a rough mix of it, sat back and listened to it. We noticed something had changed. Everyone became aware of it simultaneously. It was very strange." And of course, being susceptible to the 'Eureka!' complex, things were always changing. "Even at the very last session we totally changed a bunch of the songs that bore no resemblance to themselves." The end result — a meisterwerk. Hear for yourself.

Despite the similarities heard in the array of sounds present throughout any Fridmann-related project, he feels that people are usually misled thinking that there is a mystical "Trademark Dave Fridmann Sound". Fridmann himself wishes to set straight what a producer's role really is and what it should be. He feels that a good deal of his work is purely contextual in nature. "I don't adhere to a formula. Under the best of circumstances, when things are going right, what you hear more than anything, is what the band wants. It happens to certainly be that many of the groups I work with like and use the same types of sounds. It makes no difference to me. I can't qualify one sound as being better than the other. My job as an engineer and producer is to find out what those people want and do just that." He continues with a logic-laden dogma that once again recalls his 'revelation' story; "People call me and say they want a Flaming Lips drum sound. I reply usually with a 'you mean you want to hire Steven [Drozd] to play on your record?' This is because it comes from him, not me. I just put up the mics. Sure I have an idea of how to capture a good sound but really, when a band is good, it's good. You're set. You have to stay out of the way." He dictates that the key to having a good result in the end product begins with the artist. "They have to have a strong idea about what they should sound like, and I've been lucky to work with people like that." After taking one quick breath, he continues his common sense-based attack, "Look, this Fall I've got a line-up that includes Low and Godspeed You Black Emperor! How far out of my way would I have to go to suddenly be a bad producer working with these bands? What would I do to make a Jonathan Richman record sound bad?"

Another important professional threshold of rationale he lives by surfaces in the conversation. "If it had to come down to it, I'd rather work with a crappy band that are friendly anyday than a great band that are a bunch of assholes. This job involves working with people, so it matters. If I wanted to work with assholes, I'd have gotten a corporate job." Given the lengthy work days that both a musician and engineer share in close proximity, his point is very clear.

The year 2000 will definitely be a rewarding year for Tarbox Road and Fridmann, and always exciting. After the off-the-floor Japanese Number Girl sessions, his next client will be Sparklehorse. "There are only two of them [Mark Linkous and Scott Minor]," he explains, "so I'll go back to having to slowly build the songs; although it'll still be organic. After that, Dot Allison (a Scottish singer) is coming in and we're going to do a lot of computer-based work. What I love, and is fun about this job, is that it changes all the time." Fridmann is glad to be away from the cloud of the megalopolis music business and would rather just work. "I live in the sticks. I work 12 hours a day. There is no entertainment industry here. People around here don't care if something is #1 on the charts. They probably wouldn't care unless they saw something about it on [the TV show] Entertainment Tonight." Set aside the odd chance exposure to other's work from the outside world (he vehemently admires the production skills of Tchad Blake, Jon Brion, Nigel Godrich, Bryce Goggin, Jim O'Rourke and Brian Paulson), he is content on getting home to his family at the end of a long day and reverting to absorbing two therapeutic albums which have taken permanent residence upon his cerebral tastebuds — the eerie John McLaughlin guitar-threaded Miles Davis classic In A Silent Way, and The Cure's Disintegration.

By the way, Dave wishes to thank his mom and dad.

Sparklehorse. Low. Mogwai. Godspeed You Black Emperor! The Flaming Lips. All five are amongst the most talented and expressionate artists this planet currently has to offer. And they will all be making the trip along the New York State Thruway this year with Cassadaga as their destination. And Dave Fridmann will await their arrival at his bunker of self-sufficiency. He'll lend them his helping ear, friendship and act a conduit to their resilience. And more will follow. Oh... and add in a band called Mercury Rev to the roster. He's a member, remember? He plays bass, and sometimes keyboards. You will be let in on a secret — they have already returned and have begun to record the follow up to 1998's critically acclaimed Deserter's Songs. And, in the same work ethic as the late great filmmaker Stanley Kubrick, they are taking their time, as usual. "Who knows when it'll be done," he says humbly, "when it's finished, it'll be finished."