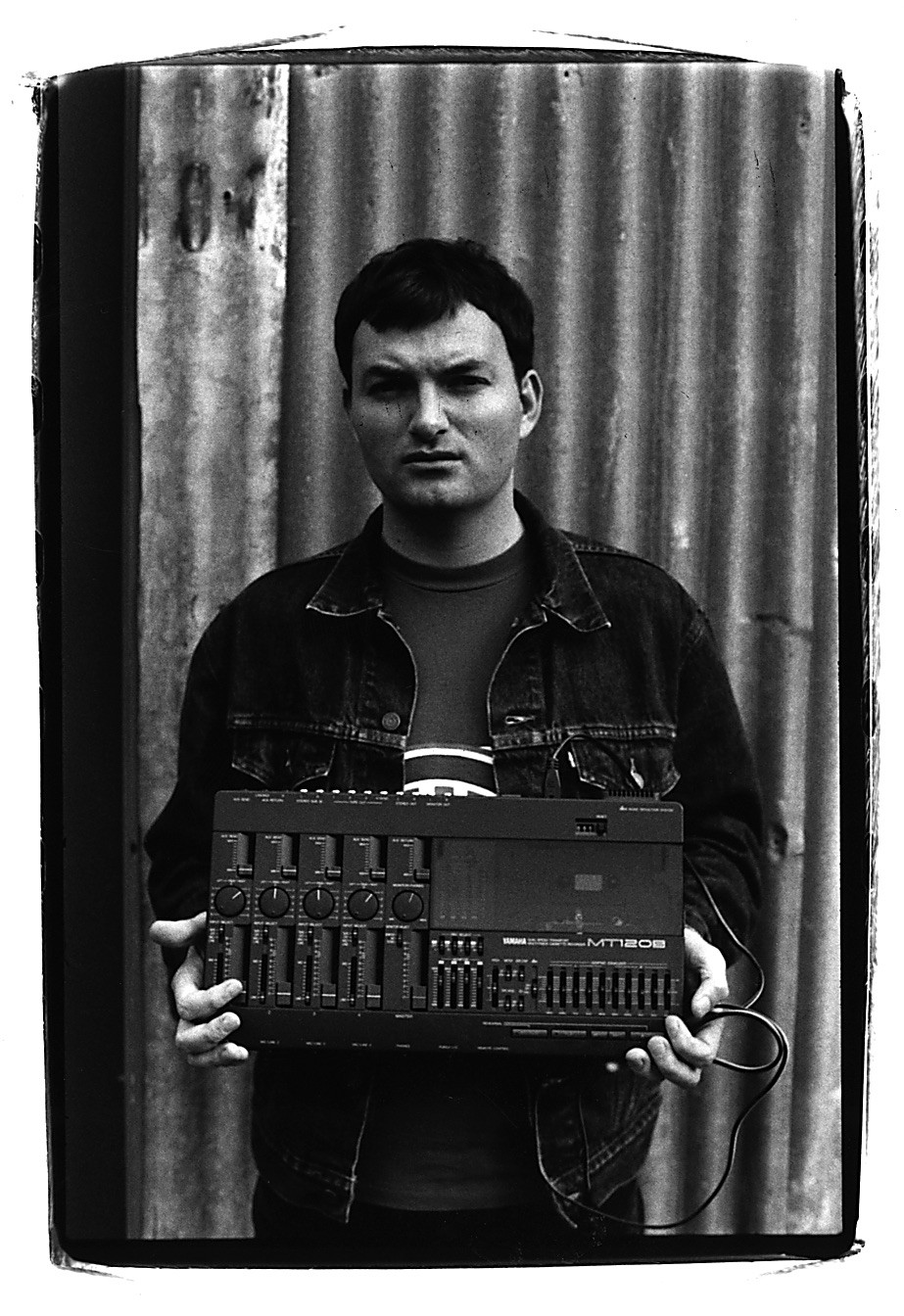

While puzzling through the intricacies of home recording (i.e. knowing what to do when you can't hear yourself through the headphones), San Francisco's Beulah managed to concoct two LPs of brittle, rousing pop.

And now, with the help of indie producer John Croslin (Guided By Voices, Spoon), [Tape Op #32] Nashville-based mixer/engineer/producer Roger Moutenot [#20] and Tiny Telephone studio owner John Vanderslice [https://johnvanderslice.com/], they're recording in a real studio, with a real budget. Are they in over their heads yet? We talked with Beulah's Miles Kurosky, Bill Swan and producer John Croslin.

Beulah started out as a bedroom project, singer and main songwriter Miles Kurosky and multi- instrumentalist Bill Swan nestled in Kurosky's apartment working out three-minute pop nuggets — as inspired by the Beatles and power pop architects like Badfinger and the Small Faces as they were by mid-'90s indie folks like Pavement and the Apples in Stereo. Lead Apple Robert Schneider even lent a hand on their early recordings, lending a mixer's hand and luring the group into the lo-fi hipper-than-thou domain of the Elephant 6 Recording Group.

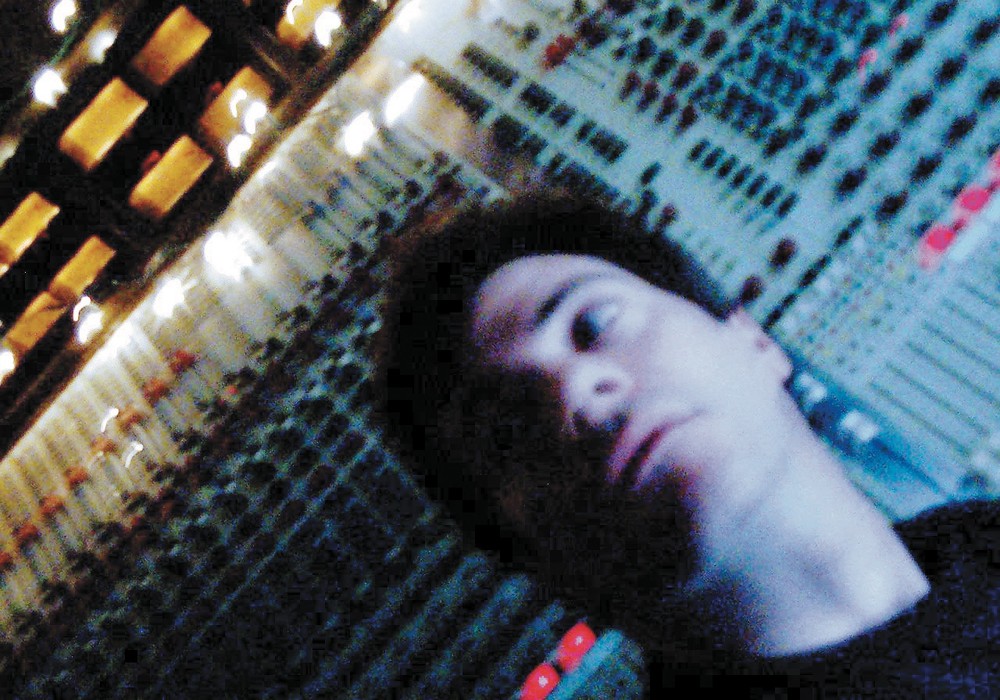

But at the tail end of the '90s, it became clear than Kurosky's sights were set higher than love from a bunch of scruffy horn-rimmers. Signing to the semi-major Capricorn label (home to artists like 311), the group, now grown to 6 members, suddenly had a realistic budget for their records. And in the fading glow of their internationally (though still critically, not fanatically) acclaimed When Your Heartstrings Break LP, the next record looms large. You get the sense talking to them that it has to sound clean enough to break through the glass ceiling of NME and college radio, but still retain enough bite and originality to avoid copping to perceived consumer demand. Beyond that, Kurosky, fresh from a stay in Japan and, from the sounds of it, a bitter break-up with his gal, is determined not to repeat himself.

"I remember we all sat down before I left for Japan, and I said, 'I'm going to leave you tapes. I want everybody's individual voices, I want you just to figure shit out on your own.'" Kurosky explains, sitting tensely (he always seems on the edge of jumping up and either throwing a fit or launching into song) in Tiny Telephone, where the band are finishing mixes for the record. "On the last record more than this one, by far, on the harp strings I came in and said, 'Here's the string line, here's the horn line, here's this, this and this,' and maybe a couple times somebody would come up with a couple lines here and there. But for the most part it was me, and I think a lot of times people felt like, 'Oh, okay. Miles knows what he wants and I won't even bother with it.'"

"On this one I said, because I found myself repeating myself, I said, 'I don't want to do this again, the same string lines and the same horn lines, I want you guys to do it.' And if you listen to what Beagle [Bill Evans] wrote and what Swanney [Bill Swan] wrote, and Pat [Noel], they're so different, they all sort of worked."

The sound of this collaborative recording style becomes apparent when you hear any of the new songs, although they all sound like trademark Beulah — gamboling verses, with instrumental textures ranging from simple indie guitar to horns, that lead into anthemic choruses, melody at the forefront. But let Kurosky explain it: "A couple songs on here go from a Curtis Mayfield sort of soul thing that Swanney wrote, into like a sort of skronky garage guitar thing that Stevie wrote into like a spacey Moog thing that Beagle wrote, and on and on. It's crazy like that and it was intentional. I think this record will be better in that way and won't sound as one-dimensional. It won't sound so Kurosky, it'll sound more Beulah."

Swan stayed true to Kurosky's wishes, as did the rest of the band, cobbling together their parts over tapes sent from Japan. "When he was gone, we all had our own tapes and did it on our own. None of us ever got together to try and figure it out," says Swan. "Five months later we were like, 'Oh hey, nice to see you again.'"

On the LP's last song (the group doesn't have the running order set yet, but they know which songs come first and last — these were two of the six songs I heard in the studio), "The Night Is The Day Turned Inside Out" (alternately titled "Slow"), string sounds created by mellotron and chamberlin analog tape loops highlight a sad, orchestrated tune. But even the song's 5 guitars...